When is PMS more than PMS?

Menstruation may be more commonly discussed than before, but a recently recognized women’s mood disorder is only picking up traction in diagnoses and treatment.

By Caroline O’Neill, Catrina Smyth and Christine Vezarov

All Eryn Speers wanted was an answer.

“I got sent to a psychiatrist who basically laughed at me,” says the 27-year-old.

In the two decades since the Toronto native started her menstrual cycle, Speers says she’s been riding an emotional rollercoaster lurching from a spectrum of feelings, like anger to depression. From 2015 to a few weeks ago, she exhausted Google’s search engine looking for scientists and studies to explain what was wrong.

The trek to a diagnosis was filled with awkward encounters and frustrated tears.

[Photo © Eryn Speers]

“[The psychiatrist] wasn’t sure what to make of it, he hadn’t really heard of it and basically threw me on a bunch of medications.”

She is one of the estimated two to eight per cent of women who experience Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD), according to the Mood Disorders Association of Ontario. Dysphoric, or dysphoria, is defined as a state of feeling unwell or unhappy in the Merriam-Webster dictionary. This disorder is most easily understood as an aggressive and emotionally debilitating form of Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS), according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders’ fifth version.

“[The psychiatrist] wasn’t sure what to make of it, he hadn’t really heard of it and basically threw me on a bunch of medications,” says Speers, matter-of-factly. “It ended up making me a lot worse.”

Officially classified four years ago, PMDD is new terrain to not only the millions of women around the world who suffer from the illness, but physicians as well.

- Women in the world 50%

- Women with PMS symptoms 85%

- Women with PMDD symptoms 5%

Suck it up, buttercup

“Until I found out about PMDD, I thought, ‘everyone else is coping,’” says Liana Laverentz, a writer and editor in Pennsylvania, U.S.A. “All women get their period, what is my problem?”

“All women get their period, what is my problem?”

Now entering menopause, Laverentz didn’t receive an official diagnosis until a few years ago.

“I wrote a lot of posts when I was under the influence of PMDD,” says Laverentz, who runs a popular blog with over half a million hits that focuses on her personal experiences with the disorder.

PMDD manifests itself in the form of severe emotional reactions ranging from blowout arguments with a partner to some mothers reporting their children are scared of them once a month.

“[There is] a list of stuff in DSM-5 that you have to have to, very specifically, meet the criteria for PMDD,” says Dr. Robert Reid, a professor at Queen’s University’s department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. “The reason for that is when we talk about it in medical circles, we are all talking about the same patient.”

For some women, a week every month can be likened to a punch to the gut. Women experience a myriad of symptoms from bloating and spurts of snarkiness to food cravings. These universal symptoms have opened up conversations about menstruation around the world.

But until 2013, up to 160 million women were excluded from at least part of that dialogue, and diagnosed incorrectly.

A gendered diagnosis

It took over a decade for Laverentz to put a title to her condition.

Her hormones were tested and she was misdiagnosed with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS). In 2009, she finally learned she has PMDD. While PCOS does have a mood component, it is predominately known for its physical symptoms, like ovary cysts, facial hair and weight gain.

“Polycystic ovary syndrome is totally different than PMDD,” Reid says. “If you got diagnosed that way, it was very wrong.”

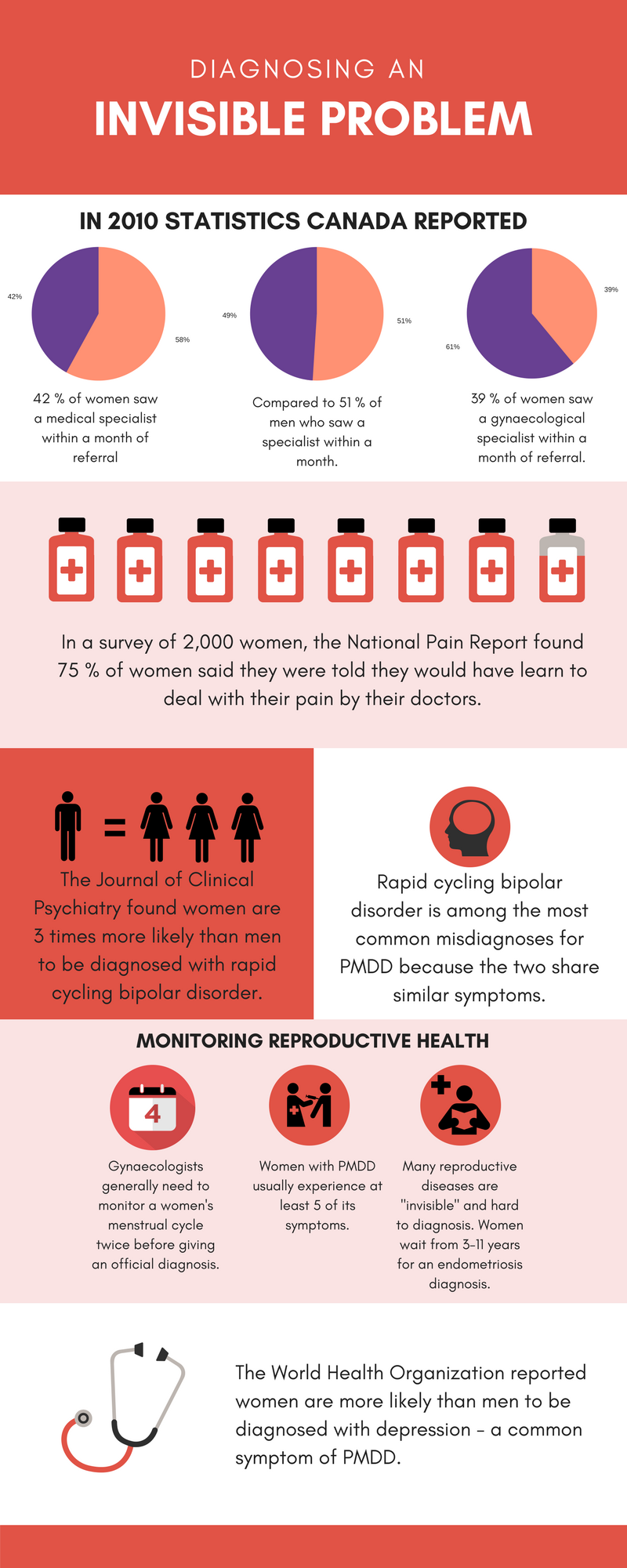

Awareness about PMDD is increasing among gynaecologists and general practitioners but there remains a disconnect between medical professionals and the public.

“Not very many [doctors] say, ‘do you have mood symptoms? Is it affecting your function?’” Reid says, “I’m not sure why that is, but it’s the way things have been happening.”

It’s not just the regular host of reproductive health illnesses PMDD can mimic, as a mood disorder it also shares symptoms with other mental illnesses.

“I see women coming in with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder because a psychiatrist had never taken a menstrual history,” says Dr. Reid.

Women are three times more likely than men to be diagnosed with rapid cycling bipolar disorder, according to the American Journal of Psychiatry. Individuals with bipolar disorder often experience bouts of depression. Likewise, the DSM lists depression as one of the top four symptoms a woman must experience to be diagnosed with PMDD.

“It’s so, so critical to distinguish between the two because one is a very severe mental disorder, and the other is a disorder but it’s a disorder that is hormone related,” says Ann Marie MacDonald, the executive director of Mood Disorders Associations of Ontario.

Getting the diagnosis right is so important because different disorders require different treatments, Dr. Reid stresses.

Women with PMDD often respond to their medication within 48 hours. In contrast, most individuals with major depression won’t see results from their anti-depressants until about six weeks.

Top 4 PMDD Symptoms

- Increased emotional sensitivity

- Anger, increased interpersonal conflict

- Depression

- Anxiety

Additional Symptoms

- Decreased interest in usual activities

- Difficulty in concentration

- Lethargy, gets tired easily

- Change in appetite, overeating, or specific food cravings

- Hypersomnia or insomnia

- A sense of being overwhelmed or out of control

- Physical symptoms such as breast tenderness or swelling, joint or muscle pain, sensation of “bloating,” or weight gain

A vicious cycle

Other than emotional behaviour one may associate with a menstrual cycle, PMDD has no visible symptoms, making it challenging to properly diagnose.

To complicate matters, the miscategorization of PMS has compounded a lack of understanding surrounding healthy periods among the public, Reid says.

Menstrual molimina is a set of mild symptoms women experience during ovulation and until the onset of menstruation, Reid explains. Food cravings, breast tenderness and fatigue are all considered normal.

“There’s no such thing as ‘I’m PMS-ing.'”

Overusing the term PMS has created a culture of women thinking they have Premenstrual Syndrome when they are really experiencing moliminal symptoms.

While 85 per cent of menstruating women do suffer from PMS, the two are separate. PMS is a possible side effect, not an obligatory symptom of a period.

A specific distinction means the difference between a diagnosis and misdiagnosis when women go to their gynaecologists looking for answers.

“It’s only when the woman brings it up, brings it forward herself,” says Dr. Reid, “that suddenly it tweaks to them [doctors] saying, ‘oh maybe this is PMS or PMDD.’”

Spotting the stigma

The mood disorder’s obscurity is also owed to the general stigma associated with mental health disorders.

In a 2016 survey of Ontario, the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) found 40 per cent of participants have experienced depression but never sought out help.

“When we are not well and we keep it to ourselves and we silently suffer, we don’t get the help that we need.”

“When we are not well and we keep it to ourselves and we silently suffer,” says MacDonald, “we don’t get the help that we need.”

While the CAMH has found mental health disorders are becoming less stigmatized in conversation, MacDonald and Reid say PMDD faces the additional burden of being associated with menstruation – a topic riddled with myths, taboos and even disgust.

“If you say three to five per cent of women go crazy every month we will never have a female president, we’ll never have a female astronaut,” says Dr. Reid.

In attempts to raise awareness to the medical requirements women with PMDD need while trying to avoid stigmatization has created a double standard: efforts have shrouded the disorder in uncertainty.

Until PMDD was recognized as a mental disorder in 2013, gynaecologists couldn’t apply for grants to begin learning more about PMDD and how to determine the right treatments.

“We could say there’s no diabetes too if you want, but when you say the disease doesn’t exist then you don’t get funding to do research for it,” says Dr. Reid.

The confusing world of treatment

There is currently no specific course of action for individuals with PMDD. Since women with PMDD experience the disorder through its different manifestations, treatments vary to reflect these needs.

A few go-to medications doctors and experts prescribe are oral contraceptives, the estrogen patch, estrogen pellets and some anti-depressants (SSRI’s), according to Dr. Reid. Discrepancies in how PMDD is researched globally factors in. For example, estrogen pellets, which are implanted under the skin, are not available in Canada.

Some treatment can work against its intended purpose, as female sex hormones, like estrogen and progesterone, can exacerbate PMDD symptoms in many women, according to a study released this year in the Molecular Psychiatry Journal.

“You definitely have to learn some self-compassion.”

“You definitely have to learn some self-compassion” says Speers, who recently started a Facebook page dedicated to raising awareness about PMDD in Canada to help those with the disorder and their family members navigate the disorder.

Looking ahead: Questions and answers

“The more that the medical world starts to look at women’s health issues, the better off everyone is going to be,” says MacDonald.

The cause of PMDD is still relatively unknown in the medical field.

John Hopkins Medicine found a link between PMDD symptoms and an abnormal reaction to the hormone changes experienced during the menstrual cycle.

Experts have observed natural hormone changes that occur during menstruation can impact a woman’s serotonin production. Serotonin is a natural mood stabilizer, and a lack of it can not only wreak havoc on bodily functions, but is also linked to depression.

The Molecular Psychiatry Journal’s study was also unable to determine a cause of PMDD, but the researchers identified an abnormal reaction to a certain protein complex by blood cells called lymphoblasts, which are part of the immune system, suggesting the possibility of a predisposition in the genes.

Ideally, science would produce a blood test for PMDD, Reid says, but he quickly acknowledges the unlikeliness of such a test occurring, at least for now.

Medical professionals and advocates like Reid and MacDonald remain hopeful about the future of better treatment and awareness of PMDD.

“Being able to talk about it, being able to say it,” Speers says. “It helps to have people understand why life might look a little differently for you – it’s very freeing.”