| Sex

change artists

of the Bay of Fundy

By Travis Webb

OTTAWA —

This shrimp has traveled a

long way. She was born and

raised on the mudflats of the Bay of Fundy – an

inlet off the Atlantic enclosed by the coast of Nova

Scotia and New Brunswick.

|

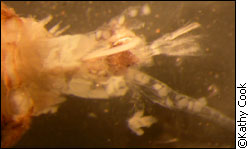

| They may be small, but Corophium

play a pivotal role in the the Bay of Fundy. |

Last summer, the tiny shrimp – she’s

no larger than a dime – made the 900 km journey

to Ottawa.

Now, she spends her time in a bar fridge

that sits on a lab bench in Carleton University’s

Nesbitt Building. She lies there quietly, waiting for

her big day.

When they’re ready for her, she’ll

be whisked onto a sterile, brightly-lit operating surface.

Moments later, the procedure will begin.

They want her ovaries.

“It’s a lot of work,”

says Mark Forbes, the Carleton biologist responsible

for the shrimp’s ordeal.

But it’s work with a purpose.

After all, these shrimp may hold a key

to the survival of one of Canada’s most important

ecosystems.

More than mud

From the highway, Peter Hicklin says the

Bay of Fundy mudflats look pretty barren. Wet deserts,

he calls them.

But walk out onto a flat and he says it’s

a different story.

| '(The sandpipers)

double their weight . . . and use that fat to fly

4,000 km non-stop down to South America.' |

“It’s like standing in a bowl

of Rice Krispies,” says Hicklin, a research scientist

with the Canadian Wildlife Service in New Brunswick.

“You hear snap, crackle, pop . . . It’s

alive.”

Much of that life is Forbes’ shrimp,

Corophium volutator. By mid-summer, Hicklin

says the mudflats swell with more than seven billion

of them.

With these incredible numbers come great

responsibility: The shrimp work the pumps at one of

the biggest gas stations in the world.

Each summer, two or three million Semipalmated

Sandpipers descend upon the mudflats to fuel up. The

bay is their only stop on their trip from the Arctic

to Brazil, says Hicklin, who has studied the birds for

more than 20 years.

“The sandpipers feed almost exclusively

on Corophium,” says Forbes. “They

double their weight . . . and use that fat to fly 4,000

kilometres non-stop down to South America.”

Take the shrimp out of Fundy and the birds

could be facing a serious fuel crisis.

|

| Mudflats like the one in

Johnson's Mills, N.B. are home to millions of sandpipers

every summer. |

But serving the sandpipers is only the

most dramatic example of Corophium’s

importance to Fundy. According to Hicklin, the shrimp

help provide nutrients for Right whales living in the

bay. Forbes says 15 species of intertidal fish rely

on Corophium as a food source.

Research even suggests the burrows the

shrimp dig help keep the mudflats – and the habitat

they provide for other organisms – from washing

away.

“Corophium is so central

to the food web that we call it a key species,”

says Forbes. “If they were to go (extinct), it

could have some very severe ecological consequences.”

It’s a threat Forbes says isn’t

that far-fetched. Corophium populations in

Europe have collapsed in the past and Forbes says Fundy

has experienced some small localized crashes in recent

years.

“(Corophium populations)

blink on and off,” he says. “(My lab) is

interested in trying to figure out what the factors

are and determine whether parasites are one of them.”

Parasites enter the picture

Forbes is a parasitologist. By definition,

he says a parasite lives in or on another organism.

Having established a home, the parasite uses its host

to derive its own nutrient requirements. In the process,

it causes some degree of harm to its gracious provider.

But Forbes is interested in more than

just these individual effects. Instead, he explores

ecological parasitology – the study of how parasites

affect the distribution and abundance of organisms in

an ecosystem.

|

| Much of Forbes' research

focuses on species which hold ecological or economic

importance. |

Over the course of his career, Forbes

has worked with several species including dragonflies

and frogs. He says most of the hosts he studies hold

some sort of economic or ecological importance.

His work with Corophium in the

Bay of Fundy is no different.

Still, Robert Poulin, a parasitologist

at the University of Otago in New Zealand, says the

European Corophium extinctions show the reach

of Forbes’ research.

“Corophium and their close

relatives are hugely abundant in intertidal mudflats

all over the world,” says Poulin. “(Forbes’)

work has potential implications that extend beyond the

Bay of Fundy.”

| 'Corophium

populations blink on and off . . . (My lab) is interested

in trying to figure out what the factors are and

determine whether parasites are one of them.' |

David Marcogliese, a parasitologist with

Environment Canada, agrees. He also says much of Forbes’

research – including his Corophium studies

– can be applied to more general host-parasite

relationships.

“(Forbes’ work) is conceptually

and theoretically interesting,” says Marcogliese.

“He’s not just going out there and measuring

things. In that sense, his work is quite novel and progressive.”

But for now, Forbes says he’s not

focused on these peripheral benefits.

He just wants to wrap his head around

the Corophium dating scene.

Battle of the sexes

Corophium males have it pretty

good.

They’re surrounded by enormous numbers

of friends and family – sometimes as many as 60,000

of them per square meter.

Better yet, most of the company is female.

|

| During mating season,

Corophium males investigate neighbouring burrows

searching for females. |

Depending on the location, Forbes says

there are anywhere from four to 12 females for every

male. While this might sound good for the guys, it presents

a potentially serious problem.

“If you have too few females, the

population may not grow as quickly,” says Forbes.

“We may get so many females that males are actually

limiting and (Corophium) can have these localized

crashes.”

In this limiting scenario, Corophium

males aren’t able to fertilize enough females

to sustain the population. An added complication, says

Forbes, is that Corophium mate on a lunar cycle.

Males only get one chance a month to meet as many females

as they can.

It’s a situation akin to asking

one mailman to complete 12 routes all in one shift.

Some female shrimp will get their delivery, but by the

end of the day, many will be left staring disappointedly

into an empty mailbox.

With so many potential mothers ignored,

population crashes in Fundy become a possibility.

Forbes turned to his specialty for an

explanation.

The idea isn’t without precedence.

Marcogliese says research out of England has shown that

a certain parasite alters the sex ratio of another species

of crustacean.

“There’s all kinds of interesting

things going on with (feminizing) parasites,”

says Marcogliese. “They can have profound impacts

on populations of organisms.”

But could this be happening in Corophium?

“Oh, it’s quite possible,”

says Marcogliese.

So Forbes and his lab – specifically

post-doc Selma Mautner – set out to harvest shrimp

from Fundy last summer. Back in Ottawa, the team began

cutting open Corophium and removing ovaries

from females and testes from males.

'It’s

quite different from anything we know about .

. . This parasite is new to science.' |

It’s a delicate process, but it

allows them to extract and identify the DNA contained

in the sex organs of the shrimp. If an invading parasite

is present, its genetic code will show up in the DNA

analysis.

“We found a parasite that is found

only in the ovaries of Corophium females,”

says Forbes.

Early returns

In the initial group of 37 Corophium

males , none carried a parasite in their testes. Meanwhile,

a parasite was detected in the ovaries of seven of the

25 females.

“We believe the parasite feminizes

(male Corophium) and continues its life cycle

by being passed on in daughters, granddaughters, and

great granddaughters,” says Forbes.

According to Forbes, the parasite can

only survive in the nutrient-rich ovaries of Corophium

females. When the female’s eggs are fertilized,

the parasite sees an opportunity to pass on its own

offspring.

But if the parasite’s progeny enters

an egg destined to become male, it panics. It can’t

live in that environment. As the young Corophium

grows, the parasite flips the shrimp’s gender.

A genetic male develops into a female.

|

| Corophium ovaries

provide ideal accomodation for Forbes' microscopic

parasite. |

Forbes says the parasite may perform this

trick by altering hormone secretions at a sensitive

stage of development. But this theory is pure guesswork

– the parasite is too small to study at Carleton.

As a result, Forbes says he knows little

about details like what harm the parasite brings its

Corophium host. To learn more, the team sends

samples of the parasite to England, where they are examined

under a scanning electron microscope.

For now, Forbes and his team must satisfy

themselves with what the DNA sequence of the parasite

tells them.

“It’s quite different from

anything we know about,” he says. “This

parasite is new to science.”

According to Forbes, the DNA sequence

also indicates the parasite belongs to a group of single-celled

parasites called the Microsporidia. Given its genetic

similarity to these parasites, one can get a picture

of how Forbes’ parasite may operate in Corophium.

For example, Microsporidian parasites

reproduce by ejecting spores. When a spore encounters

a host cell that appeals to them, it pricks the cell

with a needle-like tube and the parasite is injected

inside.

This is likely how Forbes’ parasite

reproduces.

But these details aren’t Forbes’

immediate concern. Instead, he and his team want to

document the presence of the parasite in the most female-biased

populations in Fundy. Collecting this data would be

a first step towards definitively attributing skewed

sex ratios to the parasite.

If this is established, it may be possible

to link the parasite to population crashes among Corophium.

So far, he says the numbers indicate as much.

“We’ve actually seen evidence

of a population crash and as far as we know, (the parasite)

is more prevalent there than anywhere else we’ve

seen yet,” he says.

| 'It’s possible

this micro parasite is driving the whole system.' |

Forbes says they have yet to find a skewed

population the parasite hasn’t infected. At the

same time, however, he hasn’t been able to find

a population with a one-to-one sex ratio.

Discovering such a population would help

Forbes test his theory. If the parasite hadn’t

infected these Corophium, it would add weight

to the idea that the parasite feminizes the shrimp and

threatens their numbers.

Positive parasitism?

Dean McCurdy, a researcher at Albion College

in Michigan and a collaborator with Forbes on the Corophium

Project, says the parasite may not be a threat at all.

He says by feminizing shrimp, the parasite may actually

facilitate Corophium’s enormous population.

“If you (have) nine females and

one male that can fertilize all of them . . . than all

of the females produce offspring,” he says.

With an equal ratio, five males have to

compete for five females. Consider that five factories

can’t produce as much as nine factories, assuming

they have the staff to operate them.

Similarly, nine Corophium females

can produce more offspring than five.

“It’s possible this micro

parasite is driving the whole system,” says McCurdy.

Forbes says it’s a possibility but

adds it would only work at low levels of infection.

Still, these are the kinds of effects

Forbes wants to explain. While his project isn’t

there quite yet, Robert Poulin says Forbes’ work

should provide a richer understanding of Corophium

and feminizing parasites.

“There are still many important

questions to be asked about these parasites,”

he says. “I’m certain Forbes’ work

will take some original directions.”

|

| The Bay of Fundy mudflats

would be dramatically different without Corophium.

|

Meanwhile, Peter Hicklin says parasites

aren’t a serious threat to Corophium

populations. A more immediate concern, he says, is human-influenced

changes in sedimentation rates in the Bay of Fundy.

According to Hicklin, these changes may be re-shaping

the shrimp’s habitat.

Regardless, Hicklin says any Corophium

research is worthwhile.

“I have great respect for that little

creature,” he says. “The more work is done

on them, the more we can appreciate the (need for) its

conservation.”

In the end, Forbes says there wouldn’t

be much he could do if there was a population crash

in the near-future.

Instead, he says a Corophium

collapse may actually provide a good opportunity for

further research into the tiny shrimp holding the Fundy

food web together.

“(We want to be) at least somewhat

prepared for documenting the effects of those crashes,”

he says. “We want to be Johnny-on-the-spot if

they do occur.”

|