|

Healing

the ear:

investigating corn resistance

to a fatal fungus

By Carol Crabbe

OTTAWA —

Linda Harris has always been

interested in learning "how life works." As

a result, she has been doing scientific research since

the late-'70s.

|

| Gibberella ear rot, caused by

the fungus Fusarium graminearum |

Her first published work was a paper on

the feeding habits of the white pine weevil –

research she conducted while an undergraduate student

at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia. From

there, she's worked on various subjects within genetics

and molecular biology

Now, Harris has moved east to the Central

Experimental Farm to pursue her interest in plant-pathogen

interaction and do reseach onplant disease caused by

the fungus Fusarium graminearum.

Fatal fungus

This fungus, usually called Fusarium, causes

cereal plants like wheat, barley and corn to go mouldy

and dangerous for humans and animals to eat. Harris

is working with other researchers at the Farm's Eastern

Cereal and Oilseed Research Centre to find out more

about the disease and its effect on corn.

Fusarium causes an increase in deoxynivalenol

(DON) – a toxin that is dangerous for humans to

consume. DON is also known as the vomit toxin, because

it causes animals to throw up. Other toxins can also

cause abortions in animals.

Fusarium enters corn through the silk tassels

on the ear or directly through "wounds" or

holes made on the corn's surface by insects and birds.

According to Harris, this fungus does well in temperate

climates, which is why it is so prominent in parts of

Canada. Fusarium also needs a humid environment

to develop and finds a perfect atmosphere in the parts

of Canada where corn is grown.

Corn also has limited resistance to Fusarium so

that large yields of the crop can become useless for

human and animal consumption, and cost farmers millions

of dollars in losses.

Finding out about Fusarium

Harris studies the genes of the corn plant and the

proteins these genes produce to find out what happens

when the fungus attacks a plant.

| 'Some genes are

"turned on" when Fusarium attacks

and some are "turned off."' |

To do this, Harris and her fellow researchers first

grow Fusarium in V-8 juice. The V-8 juice has

nutrients the fungus needs to grow, Harris says, so

its an ideal environment The next step is to infect

ears of corn with the fungus and see what proteins are

produced in the corn, and what genes produce these proteins.

This is the basis of the proteomic and genomic study.

The corn used for these experiments is grown on the

Farm. It is important to find out about the genes in

the plant, Harris says, because in each ear of corn,

there are two kinds: genes that are "turned on"

when Fusarium attacks and ones that are "turned

off."

Pictures of genes

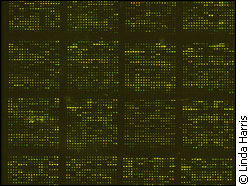

Microarrays are like photos of genes, and are used

to find out which ones work harder when the disease

attacks, and which ones work less. If a gene is "turned

on" in reaction to the fungus, it produces more

of a particular protein, and if it is "turned off"

it produces less of that protein.

|

Picture of Genes: subsample

of a microarray comparing the gene expression

levels of thousands of maize genes responding

to Fusarium infection.

|

The research seems pretty basic, but Harris says this

information is essential because the genes in the plant

can be catalogued from this process.With this information,

links can be made between resistance, genes and proteins

in corn.

Further research can then be done to isolate the specific

genes that cause resistance, and these genes can be

reproduced to make corn plants more able to withstand

the disease.

What's next?

Predictably, the groups most interested in this research

are the Ontario Corn Producers Association and Ontario

Pork Producers, who are funding her work along with

a number of smaller groups. According to Harris, most

of the corn produced in the eastern part of Canada is

fed to pigs.

Fusarium research is wide ranging in Canada

, some researchers focus on the fungus itself –

which has already been genetically sequenced –

and others, like Harris, focus on the plants it attacks.Harris

says most of the previous research has been done using

wheat, but very little has been done with corn.

With her research, Harris is in some way learning

"how life works" and in the process, helping

to heal the corn industry. One ear at a time.

|