Finding home

Those who survive Boko Haram end up in one of three places: official camps, set up by the government and non-governmental organizations; host community camps, which are more informal settlements usually housing whole villages; or, their own homes, which is happening more often these days.

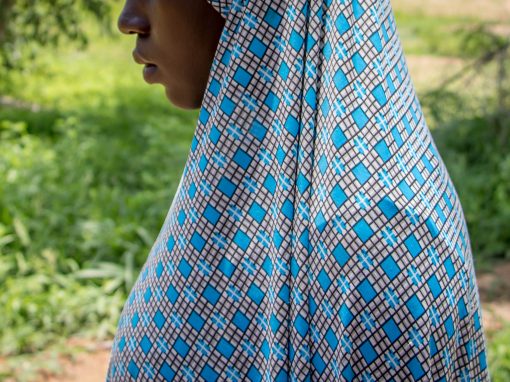

Wherever they end up, readjusting is not easy, especially for the women and girls abducted by Boko Haram. According to a 2015 report by UNICEF and International Alert, they suffer from “acute mental distress resulting from sexual, psychological and physical violence suffered in captivity.”

Even after regaining their freedom, their hardship continues.

Communities are often suspicious and fearful that women and girls who return from Boko Haram captivity may have been radicalized by the terrorist group, which has used them for suicide missions in various parts of Nigeria’s northeast.

And when they return pregnant or with children born out of their experiences in captivity, the stigma from the community is two-fold.

“They say things like a child of a snake will always be a snake, that these are the Boko Haram of the future,” said Chitra Nagarajan, a humanitarian expert who works on human rights, peace and security in northeastern Nigeria.

The 2015 report highlighted that these children are seen as having “bad blood” passed on by their fathers.

The women are called “Boko Haram wives.”

In communities where many have suffered the brunt of Boko Haram’s horrific atrocities, to be called by these names is not only derogatory, but a clear sign of danger, said Mausi Segun, a senior researcher with Human Rights Watch. Some families have sent their women and girls away to live with relatives in other places to keep them safe, because these women and girls fear retaliatory attacks.

Even within families, it’s hard to find acceptance. Only mothers are most likely to readily accept their children back, said Nagarajan.

Some women and girls won’t even admit that they were held. Those who do acknowledge it find it difficult, if not impossible, to get help.

Needs

The needs in northeastern Nigeria are enormous. Boko Haram has caused damage across the region, not just to the women and girls. Whole communities are suffering. In fact, this conflict has plunged some areas into a danger of widespread famine. The World Food Programme stated that Boko Haram violence, “coupled with the existing challenges of extreme poverty, underdevelopment and climate change…has led to one of the most acute – and sorely neglected – humanitarian crises in the world.”

“We have a general lack of services in terms of quantity as well as quality,” said Nagarajan.

This is the reality that many of these traumatized women and girls return to. They have vast needs, too. One of their most pressing needs is special healthcare.

Women who return pregnant or with children need supports such as maternal and pre-natal care. They need to be able to make choices about what happens to their pregnancy and should have options for adoption or even access to safe abortion if that’s what they desire, said Nagarajan.

But in the Penal Code for Nigeria’s northern states, an abortion is categorized as an “offence affecting the human body.” A woman who seeks one can be punished “with imprisonment for a term which may extend to fourteen years.” They could also face fines. The law only permits safe abortions when a pregnancy puts a mother’s life in danger.

This forces women and girls who want abortions after being impregnated by Boko Haram terrorists to consider unsafe options.

The search for justice is another aspect that many women and girls don’t know how to even begin, said Mausi Segun, a senior researcher with the Human Rights Watch who has interviewed more than 100 of these women.

Women and girls who managed to survive nightmarish atrocities at the hands of Boko Haram have had to return to their lives without any form of counselling or support to help them deal with their trauma.

It is perhaps not surprising that when some of them speak about what they endured in captivity, they do so without emotion, in a matter-of-fact tone. It’s their way of coping.

“This is a big challenge when it comes to rehabilitation,” said Nagarajan.

“We know that even with the best of care it can take months or even years to get over even something like a single instance of rape and sexual violence, let alone something of this nature. I don’t think it’s something that’s an easy thing but I think it’s a long-term process that is needed.”

Add that to the fact that international and national non-governmental organizations have only recently started to provide support for those who have returned from captivity.

“The humanitarian response as a whole was delayed,” said Nagarajan. “There were people doing some work but this really only started in earnest last year.”

This work did not start on time because of some issues of funding, Nagarajan added.

The 2015 UNICEF and International Alert report states that “government programmes are limited.”

For example, the Office of the National Security Adviser in Nigeria launched a short-lived rehabilitation programme offering medical care, psycho-social support, post-traumatic counselling, de-radicalisation and livelihood programmes for women and children associated with Boko Haram, in January 2015. According to the report, the programme lasted until the end of that year.

Thus far, government actions suggest rehabilitative support for the women and girls is not a priority right now. It has placed more emphasis on winning the war against Boko Haram, on reclaiming territory so that the more than 1.8 million displaced people can return to their homes.

Possible next steps

A rehabilitation programme will have to include everyone, and not only women and girls returning from captivity, said Nagarajan. If these women are the only beneficiaries of interventions, they could be targeted by members of their community.

“There’s a bit of a continuity between what their needs are and what the needs of other people are,” she said. “We are talking about issues of healthcare, psychosocial care, these are broad-ranging needs that everybody requires, some to more extent than others.”

The Nigerian government may not have the resources to provide for the women and girls, but it bears responsibility for ensuring they can get help by creating an environment that allows international agencies and non-governmental organizations to step in. According to Segun, this means taking an active role in coordinating the efforts of these organizations.

These women and girls, as well as others who will return from Boko Haram in the near future, still have a long road ahead to proper recovery and finding home. And the effects and implications of what they survived will be felt for generations to come.

Click on an image below to read the story