Tags

Related Posts

Share This

Body casting: feminism’s newest shape

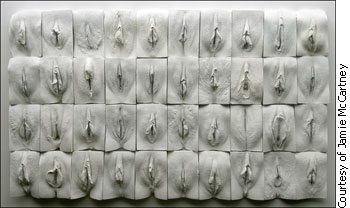

British sculptor Jamie McCartney has been approached by medical textbooks looking to use photographs of his artwork for sections about vaginas. He’s been told his “Great Wall of Vagina” is the best source in the world for showing what normal vulvas look like.

The Brighton-based McCartney created his “Wall” as a commentary on the phenomenon of women getting cosmetic surgery because they don’t like the look of their vaginas. The wall is made of plaster casts of women’s vaginas. McCartney has completed 360 casts and hopes to do 40 more before the piece debuts this year at London’s Hay Hill Gallery.

One cast panel of Jamie McCartney’s “Great Wall of Vagina.”

Says McCartney: “My work is often a celebration of the female form, but at other times it is more of a celebration or even investigation of what it is to be female.”

He says he likes the immediacy and honesty of casting. “I capture people as they are, rather than creating my version of how they are.”

Casting allows the artist to experiment in a variety of ways. Some of McCartney’s casts are done of a subject’s entire body, while others, like those in the wall, are of a specific area or body part.

This accuracy is what makes body casting so popular today. It is even used in psychotherapy (often with an emphasis on full-body form, not just genitalia). By seeing themselves as they really are, women are able to overcome body-image issues, said Jamie Hurst, program coordinator at Hopewell Eating Disorders Centre in Ottawa.

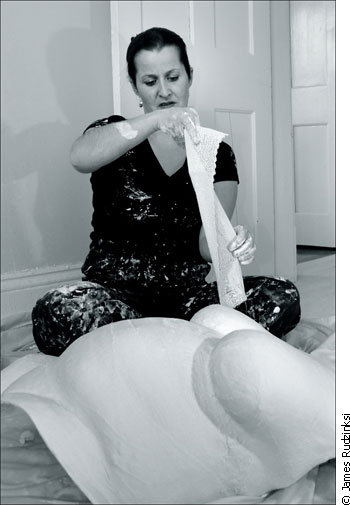

McCartney covers a live subject in plaster for a full-body cast.

McCartney covers a live subject in plaster for a full-body cast.

Body casting was used in Hopewell’s prevention program for girls aged 11 to 14. “We used the body casting with them as a means of helping them to recognize that all of us have different body shapes and sizes, and no one shape and size is any less beautiful than another,” Hurst said.

The artist behind the mould

McCartney began his body-casting business in 2006. He juggles many projects as an artist, photographer, sculptor and body caster, but admits his fine-art ambitions have taken somewhat of a backseat with the success of his casts.

While artists have found commercial success in casting, others pursue the vocation from a medical standpoint.

Keon was shocked at how beautiful her body was when she first saw a cast of herself.

Julie Keon, an Ottawa body caster, began as a doula and has a background in social work. She began casting pregnant women’s stomachs after a birthing client asked for help with an at-home casting kit she’d bought.

Keon says she thinks more women would benefit from the use of body casting in psychotherapy. Like most of her clients, Keon herself was shocked at how beautiful her body was when she first saw a cast of herself. She said she thinks every woman could benefit from that experience.

Changing outlooks

To inspire and empower more women to accept and love their bodies, Keon displayed her casts in March 2010 as part of the “Breaking the Mould” event held at Carleton University, organized by students for a women’s studies class focusing on activism. Then in July, Keon’s “Goddess Project” was displayed at Ottawa’s Stepping Stones Art Gallery. Both projects featured casts of women of all shapes and sizes who had been through various traumas or challenges, including sexual abuse, rape, mastectomies, eating disorders and physical disabilities. The casts were anonymous, but each was accompanied by a plaque detailing the subject’s story.

Julie Keon’s “Goddess Project”: casts and stories from a variety of different women.

“I hope that women can look at their bodies differently, that they can celebrate their bodies and maybe celebrate things like that they’re healthy, that they can walk, that they’re strong,” said Keon.

“By getting casted, it really gave me a chance to see myself from the outside,” said Anna Bélanger, who had her cast done by Keon.

She said getting the chance to see her body as it really was completely changed the way she felt about herself, for the better.

Body casting is an effective tool in feminism because it doesn’t go deep into theoretical issues, said Patrizia Gentile, a professor of women’s and gender studies at Carleton University. It is engaging, easily understood and accessible for a wide audience. It powerfully puts forth a feminist message by “visually representing the diversity of women’s bodies in an immediate way,” she said.

Keon adds plaster to strengthen a cast before she paints it.

Gentile pointed out that women’s bodies have traditionally been thought of as weak and inferior, and to challenge these ideals by proudly and unapologetically displaying them delivers a crucial message about accepting the great diversity of the female form.

The women whose vaginas are included in the wall are a real representation of diversity. There is every race, sexual orientation and age – the youngest being 18 and the oldest 76.

There are also six transgendered individuals included: three male-to-female transsexuals who have undergone gender reassignment surgery, and three female-to-male transsexuals who were undergoing hormone therapy at the time they were cast.

McCartney says he feels the absence of a victim of female genital mutilation is a real gap in the wall. He is actively searching for such a woman to participate, but much to his disappointment, no one has yet come forward. He says he sees that as a missed opportunity for drawing attention to the “barbaric practice.”

McCartney at work on a body cast: “I capture people as they are.”

The Great Wall of Vagina not only encourages the acceptance and celebration of each unique woman, said Gentile. It and similar projects serve to de-mystify the genitalia and challenge taboos about vaginas by displaying them outside a sexual context.

McCartney, who considers himself a feminist, said he’s very glad to have helped women think more positively about their bodies. “It is humbling,” he said. “It thrills me that I have done something right with my life. It is easy to change peoples’ lives for the worse, but to actually change them for the better on a grand scale is a miracle, it’s amazing.”

Related Links

The casting process

When preparing to cast a subject, Julie Keon covers her studio floor with clean sheets, and cuts up rolls of hospital-grade plaster gauze into strips.

To relax her client, she lights a candle, puts on soft music and spends a few minutes chatting with her.

Once ready, the client removes all her clothing except her underwear, and Keon applies Vaseline to the subject’s body. Clients are instructed to wear their oldest underwear, since they will be destroyed in the process.

Keon works with her subject to find a pose that is comfortable and looks good. Most of her casts are with the subject sitting, as pregnant women can get lightheaded if they stand for too long.

Keon dips the strips of plaster gauze into warm water and smooths them onto her subject’s skin, creating a few layers to form a sturdy cast of the subject’s body. The cast does not normally enclose the subject’s back.

The plaster dries as Keon works, and after about 20 minutes she gently pulls the cast off. The Vaseline helps it come off easily.

While the client showers to remove the bits of plaster from her skin, Keon adds more layers to strengthen the cast, leaving it to dry for a few days.

The finishing process involves a lot of sanding with different grades of paper and screens. A layer of Gesso (a plaster-like liquid) is added, to seal the cast in preparation for painting with a matte or high-gloss varnish.

When completed, the cast is delivered to the customer, ready to hang, about four to six weeks after the initial session.