Tags

Related Posts

Share This

Record labels, who needs ’em? Young musicians market online

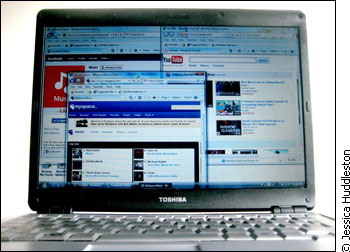

Sign up. Log in. Entering the world of MySpace is overwhelming at first. Everyone wants you to add her or him as a friend. Everyone wants to see who you are and why you are there. Then, there it is — the brilliance behind these social networking websites — flashing from different sides of the screen. “Are you a musician? Click here.” “Record, upload and share videos? Click here.” New artists quickly realize that the tools to broadcast and promote themselves are a click away.

Emerging artists are using online utilities to do what record execs used to: launch a career.

This trend of online music promotion invites the question — what happened to young artists wanting desperately the attention of a major record label? It seems nowadays all it takes is an online-savvy musician to set up a MySpace, Facebook, Twitter or YouTube account to reach a fan base. It seems the idea of the man in the suit sitting in the back of a smoky local bar, waiting to sign the unknown artist, is something of the past.

“It’s extreme at this point in time,” says Jason Feinberg, founder of On Target Media Group (OTMG), a digital music-marketing firm. “Most record labels are starting to realize they are no longer in the business of breaking music.”

Feinberg — whose company has a shiny list of campaigns that include Steve Vai, Van Morrison and Ringo Starr — helps already established musicians reach out to their fan base through online and digital engagement. He admits he would be reluctant to take money from a new artist, when artists can do the initial campaigning themselves online.

“The artist is in control now,” says Feinberg. “They can have a homepage, get on the core social networks and maintain a stream of content to their fans. They have the ability to share.”

Meredith Luce, an independent local musician who has been playing in Ottawa for almost six years, says she has remained unsigned because labels are generally “cliquey” and fixed on branding an artist’s identity. As an alternative, Luce is active in promoting herself online. Not only does she have live footage, photos and music downloads posted on her MySpace and Facebook pages, but she also sells hard copies of her recordings through a digital distributor, CD Baby, the largest online distributor of independent music.

The Oregon-based CD Baby allows any musician above the age of 13 to join their database, and it all starts with what seems to be the most popular step towards early artist success — signing up as an online member.

Once the artist is a member, the online warehouse creates a page for the artist on its website, digitizes the artist’s music and album information, and makes the music available to the masses worldwide. The distributor proceeds to ship music to fans, as well as to other online music databases like iTunes and Rhapsody.

‘Now, record labels come into the picture later. If they see someone already has a really good online fan base, they’ll pick you up.’ — musician Meredith Luce

For one physical CD or vinyl sale, the website asks the musician for a $35 sign-up fee and then a $4 portion per album sale. CD Baby has over 1.6 million customers and pays over $111 million in royalties to artists yearly.

“It’s a huge network out there,” says Luce. “I get people from across the world stumbling upon and buying my two albums.”

So does this mean that emerging artists don’t need record labels anymore? Not exactly, says Luce.

“Now, it seems record labels come into the picture later. If they see someone who already has a really good online fan base and has put in the time and money to sell themselves, they’ll pick you up.”

Feinberg corroborates this point, saying that it is rare to have a new band catapult to success by signing a contract with a record label. He states that for a label, it no longer makes sense — from an investment and revenue standpoint — to take an unknown band and move them up the ranks.

“Once the band already has that consistent fan base and has sold music, a major record label can obviously turn up the heat very quickly for them,” says Feinberg.

Tony Sutherland, coordinator and professor at the school of music business management at Durham College in Oshawa, says that to have an unknown act become a runaway success completely on their own is rare, but many contemporary artists are following the online-then-label model. Vampire Weekend, Lights and Jamie Robinson are all examples of artists who did the digital work themselves and then were taken to the next level by the major label.

Meredith Luce has never been signed to a label; instead, she markets herself online.

“Success breeds success,” says Sutherland. “The industry will help to build a successful regional act to a national and an international force.”

According to Feinberg, the changing face of the industry is not settling well with record label executives. The major labels are hesitating to begin the significant shift from the traditional business model to one that is rooted in online talent discovery, networking and sales. In order for the major labels to re-enter the start-up scene and profit off unknown talent again, they need to integrate large online elements into their business models — because that is where the money is.

If the shift from traditional to digital does not happen soon, the labels could crash and burn, says Feinberg.

“The people at the top might have an idea in the back of their heads of what they need to do,” says Feinberg. “But as they sit there with their multimillion-dollar salaries, it seems they can’t help but reminisce about the good old days — they don’t want to let it go.”