Tags

Related Posts

Share This

The healthy balance at Ottawa’s artist-run galleries

Visitors to SAW Gallery in downtown Ottawa won’t be greeted by a front-desk host or a tour guide in uniform.

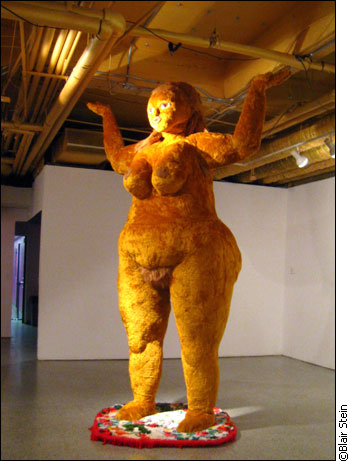

Instead, they’ll be confronted by a naked goddess, 12 feet tall, made of felt and plush, complete with emphatic pubic hair. She’s standing on a latch-hook rug, and her head almost disappears into the gallery’s exposed ceiling. She looks like the idol in some crazy version of an ancient Greek temple.

Apparently, this isn’t a traditional art gallery.

SAW is only one of two artist-run galleries in Ottawa, along with Gallery 101 at Bank Street near Somerset. Artist-run centres, which have been operating in Canada since the 1970s, have by definition a board of directors containing a majority of artists. According to Daniel Roy, Director of the Artist-Run Centres and Collectives Conference of Canada, the spirit of the artist-run centre runs far deeper than that.

What’s important, he says, is “the way these places work and what they do with the services they provide to artists.” What they provide is freedom.

“Artists working in an artist-run-centre context have much more freedom to do what they want to do than those who are working at a bigger institution,” he says.

Guardian spirit: the goddess at SAW Gallery on Nicholas Street.

Unlike commercial and public galleries, artist-run spaces do not depend on selling exhibited works or tickets to make a profit. Instead, they run as not-for-profit institutions, relying on operational and project grants, memberships and fundraising.

And it’s all controlled by artists.

Money matters

“I’m shocked when I hear this misconception that artists don’t know how to manage money,” says Roy. He says that artist-run centres are proof positive that “artists are the best to manage money because they have so little that they have to work with what they have.”

Pat Durr has been creating art in Ottawa for over 30 years, and says that she too has encountered the notion that artists are bad at business.

“We’re not a bunch of artsy-fartsy, inept people just dancing around and looking for inspiration,” she says. “Any artist that has to stay alive and functioning over any period of time has got to learn to be a decent businessperson.”

Durr says that artist-run centres can be seen as one solution to one of the biggest problems facing Ottawa-area artists — a lack of exhibition space.

“If you can’t find places to start exhibiting, then it’s very hard to find a clientele who can support you,” she says. She says that artist-run centres provide a different service than other galleries “because the people running artist-run centres are artists, and they understand the issues and the problems we face.”

Because artists are in control of how the art is presented, says Stefan St-Laurent, curator at SAW Gallery, they can identify with the exhibiting artists and present them as well as possible.

“Public galleries have a lot of pressure to perform, sell tickets and try to organize blockbuster exhibitions,” he says. “Instead, we really want to show the artist today without any censorship whatsoever.”

‘We’re not a bunch of artsy-fartsy, inept people. Any artist that has to stay alive has got to learn to be a decent businessperson.’

— artist Pat Durr

St-Laurent says that his curatorial experience would be completely different if he was at another sort of gallery, and he wouldn’t have it any other way.

“If I would be working at a public art gallery, I would probably encounter a lot of obstacles,” he says. “I’ve never been told I can’t do something because it’s contentious or potentially controversial.”

St-Laurent also says he has a love for the off-beat, which often goes ignored in traditional galleries. For instance, in 2003 St-Laurent curated an exhibition called Scatalogue, featuring all things fecal, and told the Canadian Press that he was excited to break art’s “last remaining taboo.”

Granting and raving

The artistic freedom of artist-run centres has allowed St-Laurent to bring shows like Scatalogue to SAW, but it comes at a price. Artist-run centres rely on funding from federal, provincial and municipal organizations like the Canada Council — curators’ and administrators’ estimates range from 20 to 75 per cent of operating costs — and they need to be accountable. Scatalogue, for instance, was called a waste of taxpayers’ money by a Canadian Alliance MP when it premiered in 2003.

Leanne L’Hirondelle, the director and curator at Gallery 101, says that she always remembers that she is “beholden to [her] funders.”

Even so, L’Hirondelle has brought cutting-edge shows to Gallery 101. Recently, she exhibited works by First Nations artist Roger Crait, featuring brightly coloured metropolitan landscapes literally exploding — a highly controversial view of the First Nations experience.

Shopping for art at a SAW fundraiser.

Gordon Hatt, who runs the Contemporary Art Forum in Kitchener, says he also keeps his money in mind. “Each funder has a different point of view and different interests,” he says. Even so, the vast majority of provincial and federal grants are peer reviewed — the organization’s eligibility for funding is determined by other arts administrators — and Hatt says he knows he is in good hands.

“If we think [a show] is really good, then we’re pretty sure that our colleagues at other organizations think it’s a good thing, too,” he says. “Then we know that we’ve got our act together and will be reasonably well supported by the peer-reviewed councils.”

Both SAW and Gallery 101 supplement their government funding with other initiatives. They host fundraisers and sell memberships, and “have things that make me really tired, like we rent out our space to groups and events,” says L’Hirondelle. “It makes for a lot of long days sometimes, but it helps.”

Present tense

These fundraising efforts might help, say both St-Laurent and L’Hirondelle, but they’re just not enough.

The question comes down to funding. Gallery 101 can’t fix Ottawa’s lack of exhibition space on its own, says L’Hirondelle, because it faces the same pressures.

“I don’t think we can totally fix all of the problems because we’re limited by the same things that are limiting the artists,” she says. “If you look at how many submissions we get per year and how much space we actually have, your chances as an artist of getting art in an artist-run centre are pretty small.” She estimates that fewer than 10 per cent of the submissions received end up in a gallery.

Gallery 101’s minimalist space on Bank Street, downtown.

Like the artists themselves, Ottawa’s artist-run centres are suffering from a lack of exhibition space. SAW has been in Ottawa for over 35 years, and Gallery 101 recently turned 30, but their spaces seem to be getting smaller and smaller, says L’Hirondelle. SAW is located in what St-Laurent calls “a glorified basement with exposed ceilings,” under the Mackenzie King Bridge, and Gallery 101 is in a loft-apartment-sized space on Bank Street.

Even so, these galleries play a vital role in the Ottawa’s arts community. Peter Honeywell, executive director of the Council for the Arts in Ottawa, says that artist-run centres provide a youthful glimpse into Ottawa’s art scene.

“The fact that those galleries have been able to stay for 30 or 40 years shows that they’re obviously finding a clientele,” he says. “It’s fantastic that we’re starting to see a younger market exploring what’s available through their own artists in their own community.”

Artist-run centres, says Honeywell, are constantly “balancing the needs of the artist…their artistic goals…and that they have the income to make the space work.”

According to Roy, it’s this sense of balance that ensures that artist-run centres are an “important complement to the visual arts in Canada.”

“It’s all part of a delicate ecosystem,” he says. “We all have a spot in this ecosystem and every spot is important, [but] artists are in the best place to know what is good for them.”

Related Links: