Tags

Related Posts

Share This

Creation by destruction: the rise of glitch art

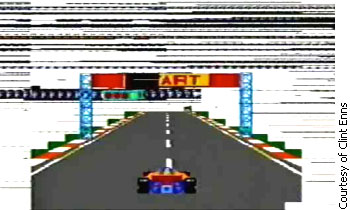

As Clint Enns pulled apart the wires inside his Atari computer, the world of the racing videogame onscreen began violently to collapse. Dozens of lines and chunks suddenly emerged from images of the sky and ground.

Glitch, please. Digital artist Carrie Gates says glitch will gain more respect once critics understand the artists’ methods.

Glitch, please. Digital artist Carrie Gates says glitch will gain more respect once critics understand the artists’ methods.

Flashes of blue, yellow and purple static swallowed the car and roadway whole. Even stranger was the fate of the “start” sign hanging over the pavement. “Every time I’d hit a few wires together,” the Toronto filmmaker recalls, “the ‘st’ would go away and it became ‘art.’”

The chaotic footage, shown at Gallery 1C03 in Winnipeg, is just one example of glitch art — a growing movement of artists manipulating technology to produce colourful and often abstract images. The genre has become not only the latest look in art, entertainment and fashion worldwide, but also a reflection of concerns about our technology-driven culture.

At its core, glitch art is created by running visuals through programs and devices they weren’t meant to be shown in. This is known as “databending” for images and “datamoshing” for videos. The method lets artists toy with a visual file’s code, the digital skeleton that shapes the overall image. Removing one “bone” in one spot might create a series of lines on the surface; adding a bone to another spot may change how part of the image is coloured. One popular method is “analog glitching,” the use of broken laptops, cameras and other devices to alter this file code.

Not only is it the latest look in entertainment and fashion, but it also reflects concerns about our technology-driven culture.

Because glitch artists can’t exactly control how their images will turn out, many are drawn to the genre by the element of surprise. “Errors are unexpected and exciting,” says Enns. “You can look at the canvas and say, ‘I made that? Wow that’s cool. I’ve never seen anything like that before.’” Designer and glitch artist Rob Sheridan, creative director of music acts Nine Inch Nails and How to Destroy Angels, considers the touch-and-go method to be more like cooking than painting. “The process injects new ideas, and you can react to how they feel and follow certain paths. It’s sometimes a much more inspiring way to work than staring at a blank document and relying entirely on your own brain to fill in every pixel.”

A dash of chaos

Glitching also creates vibrant and visually pleasing rays of colour, is do-it-yourself-friendly and is still very much uncharted territory. Given these features and the supportive online glitch art community, it’s not hard to see why the genre has moved steadily mainstream in the last ten years. Following the 2005 creation of the “Glitch Art” Flickr group, more and more artists have connected via wikis, blogs and forums to share their art, learn new glitching techniques, and support each other’s work. For example, South Korea–based artist Mathieu St-Pierre saw his “Glitch Artists Collective” Facebook group grow to 135 people after only one month. “With sites like Facebook, you can get genuine feedback on what you’re doing,” he says, adding that the glitch community has given him more confidence in his work. “It pushes you to not to make the same thing and try to be original.”

How to Destroy Angels is one of several music acts with glitched promo material. Clockwise, left to right: Mariqueen Maandig, Trent Reznor, Rob Sheridan, Atticus Ross.

Today, the glitch look has become part of our culture. After discovering the genre, Sheridan used Photoshop to glitch the album artwork for Nine Inch Nails’ With Teeth (2005) and Year Zero (2007) to reflect the industrial rock group’s chaotic sound. In 2009, Kanye West’s music video for “Welcome to Heartbreak” was glitched with datamoshing. In 2010, Colorado artist Kristopher Collins launched the glitching app Decim8 that lets users databend their photos with the touch of a button. In 2012, fashion designer Karl Lagerfeld and electronic musicians Skrillex and Diplo began using glitch in their ads, promotional images or videos. Glitch artwork and video have been exhibited in places worldwide including the Share art festival in Italy, Oslo Art Academy in Norway and the Vancouver New Music Festival. An annual glitch art conference, appropriately titled GLI.TC/H, began in Chicago in 2010 and has since travelled to the Netherlands and United Kingdom.

Meanwhile, Sheridan glitched the 2010 artwork for The Social Network soundtrack album (through databending) and for his own group How to Destroy Angels’ 2012 “An Omen EP” (through analog glitching). Sheridan says he chose glitch art to reflect the theme of information overload present on both albums. “It’s an inevitable reaction to the world becoming more digital. There’s just something cathartic about unleashing errors and chaos into ordered systems. It’s like bringing some humanity into the machine — imperfection being, really, the essence of humanity.”

The medium is the message

The unease with our culture of perpetual upgrading is carried by fellow glitch artists including Carrie Gates, a digital media designer from Saskatoon. “I’m really frustrated with the hyper-clean vision commercial technology is pushing forward,” she says. “I don’t like the idea that everything is so controlled and idealized. There’s so much more complexity to life that glitch art enforces.”

Similarly, as filmmaker Enns explains, it comments on our fixation with upgrading and obsolescence. “As an artist, it’s great: I have access to cheap cameras within months of them coming out. As someone living on this planet that’s slowly being destroyed due to overconsumption, it’s not so great. It’s one of the political aspects of glitch art, revealing that newer isn’t better.” Other artists, Sheridan notes, are driven by a curiosity or plain subversive urge. “Glitch draws in the type of people who get a new tool or a new device or new software, and think, ‘How can I use this in a way that wasn’t intended, and get interesting results?’”

Accidental “Art.” Clint Enns made the glitch video prepare to qualify on an Atari running the 1982 racing game Pole Position.

Some critics dismiss glitch as a mere button-pressing exercise that only produces jarring images. In their essay “Notes on Glitch,” glitch theorists Hugh S. Manon and Daniel Temkin note that GlitchBot, an automated Flickr account, parodies how repetitive the genre can be by randomly glitching and uploading images to Flickr’s “Glitch Art” group. Many appear as similar blocks of static. Artist Gates counters: “It actually takes a long time and a lot of practice to hone your craft. It just looks easier to them because it’s digital. Eventually, with a greater understanding of how and why these pieces are produced, the respect will come.”

But will glitch become a victim of its own success? As the look gets co-opted into big-money advertising and promotion, will it lose that very subversive bite that has made it worthy? “I don’t think so. It proves that glitch art can sooner or later stand as an art movement,” St-Pierre says. “Commercial media will get saturated with certain glitch effects, but it pressures artists to come up with new glitches and visuals to keep the movement alive.”

What’s certain that you’ll be seeing more glitch art in years to come, as new technologies continue to provide platforms — and issues — to connect artists and audiences. “Glitch art is about trying to figure out, experiment with, and demystify the technology that we’re using,” Enns says. “That impulse will keep going.”