Tags

Related Posts

Share This

L’Oscar: Quebec filmmakers take Hollywood

Quebec’s film industry and talent have hit the world stage. The fact seemed incontestable this past year, capping a three-year noticeable trend. In mainstream movies of 2013, Quebecois directors Denis Villeneuve and Jean Marc Vallée made their Tinseltown mark with their respective hits, Prisoners and Dallas Buyers Club. Meanwhile, Louise Archambault’s French-language Gabrielle earned critical praise on the festival circuit and was considered one of Canada’s top films of 2013.

So, what gives? Why is Quebec consistently representing Canada for big-league film, and what does this say about Canada’s anglophone moviemaking?

For the 2014 Oscars, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences received a record high of 76 foreign-language submissions; all of these 2013 releases were competing for a handful of nominations for Best Foreign Language Film. It’s a huge honour for a non-English-language work, and Gabrielle was Canada’s official submission, following in the footsteps of Incendies (director Denis Villeneuve, 2010), Monsieur Lazhar (Philippe Falardeau, 2011) and Rebelle (Kim Nguyen, 2012) — all Quebec made.

Although none of the above-mentioned Canadian movies won the Oscar, their success and high profiles have helped to announce Quebec’s emergence. The nominations of Incendies, Monsieur Lazhar and Rebelle marked the first time in history that Canadian films were Oscar finalists for three consecutive years. The lucky streak was broken in January 2014, when Archambault’s Gabrielle missed the shortlist for Best Foreign Language Film (in a highly competitive year that will showcase work from Palestine, Cambodia and Germany). Yet Archambault has stated that the submission alone was a positive factor: The film has since received international buzz, and Archambault herself has seen a spike in film offers from Canada and the U.S.

Real people, real stories

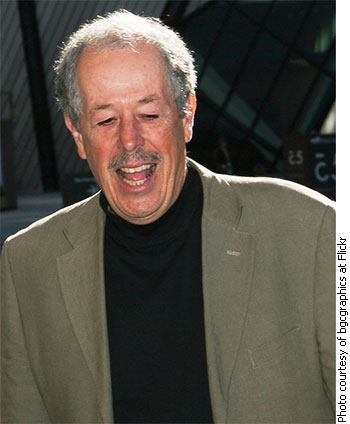

Acclaimed Quebecois director Denys Arcand earned Canada’s first best-foreign-film Oscar, for The Barbarian Invasions, in 2004.

It took several years for Quebec cinema to become a common currency in the international film market, says Quebec cinema researcher and expert André Loiselle. “It had started to find a place on the international festival market in the 1960s, but these were the very beginnings,” says Loiselle. “After 50 years of crawling its way up the ladder, Quebec cinema, as a national, smaller cinema, has pretty much reached its desired maturity and is now a regular among [Oscar] nominees.” This maturity places it among such national competitors as Sweden, Italy and Spain, Loiselle says.

In 2004, Canada brought home its first and so-far only Best Foreign Language Film Oscar, for Denys Arcand’s The Barbarian Invasions. Loiselle calls this a real turning point for Quebec cinema: “This is the best possible indication that by the early 2000s, Quebec cinema had truly found its way.”

Invasions tells the story of fifty-something Rémy (Rémy Girard), who attempts to make amends with old friends, lovers and family members upon learning he is dying of liver cancer. “When you look at Denys Arcand, his films are so good because the scripts are terrific. They are real. These are real people going through real things,” says film author Gary Evans, who specializes in Canadian cinema.

A reliance on touching, realistic scripts is one of the qualities of Quebec films, and what attracts audiences. “What Quebec is able to do is articulate stories that are compelling,” Evans says.

Typical of these compelling stories is Archambault’s Gabrielle, which deals with a subject no director had yet touched. Twenty-four-year-old Gabrielle (Gabrielle Marion Rivard) has Williams syndrome, a neurological disorder that causes developmental delays, learning disabilities and a particular proficiency for music. When she falls in love with a boy in her choir, she does everything she can to prove her independence to her family members, which causes problems when most of them disapprove of her new relationship. “It’s interesting because that [disorder] is one that people generally don’t know too much about. And it’s the core of what makes the film interesting, because the character is looking for love; she’s a lovable person, and we almost forget the fact that she’s ill,” says Evans.

‘What Quebec is able to do is articulate stories that are compelling.’ — film author Gary Evans

Indeed, Quebec cinema’s brand of realism was also developed in films such as C.R.A.Z.Y, the 2005 Jean-Marc Vallée film about a young gay man who comes to terms with his sexuality in 1970s Quebec. C.R.A.Z.Y.’s overarching themes include family relationships and conflicts, religion, and homophobia. It currently holds a 100 percent rating on Rotten Tomatoes, and won in almost every category at Canada’s 2006 Genie Awards. As Jette Karnion from Cinematical wrote, “C.R.A.Z.Y. succeeds by touching on the kinds of events that could happen to any of us.”

Poignant, realistic, original. Louise Archambault’s Gabrielle features a vulnerable character with a disability, Williams Syndrome.

This brand of realism seems to be something the Academy is fond of for the Best Foreign Language Film category, which was initially created to recognize smaller, art-house films with less production value. It started out by showcasing the European art films that emerged after the Second World War, and it still tends to focus on that particular type of cinema, says Loiselle. “The foreign film category is really there as a counterpoint to Hollywood blockbusters. And that, traditionally, is where Quebec has done very well.”

Although the aforementioned characteristics help Quebec’s films stand out on a global stage, they are advantaged by another evident element — the films are spoken in French. This of itself makes them contenders for the Best Foreign Language Film category; and their subsequent buzz is often followed by acquisition by powerhouse Hollywood distribution companies. Distribution rights to Gabrielle went recently to Entertainment One, which means the film will be shown in theaters across the U.S.

Anglophone cinema: Dwarfed by Hollywood

Yet this opens another question: Why are the Canadian films securing U.S. distribution the ones that are in a foreign language?

The answer may have to do with the fact that English Canadian films are competing nose-to-nose with Hollywood films. Canada’s main curse is that the films produced are in English, but with an exponentially smaller budget.

“A typical Hollywood film starts at a budget of maybe $20 million, and then you go up to $50 million, and then blockbusters cost hundreds of millions of dollars,” says Evans. This money is unavailable in Canada — for example, Telefilm Canada, a crown corporation that funds Canadian feature films, has an annual budget of $100 million — and investors traditionally are not keen to invest in films with no guarantee of a profit. In fact, Jean Marc Vallée’s Dallas Buyers Club was initially intended as a Canadian feature film, but Vallée has admitted he had to move the production to the U.S. to find funding for it. The casting of U.S. star Matthew McConaughey also secured funding as well as buzz for the film.

Crazy like a fox. Director Jean Marc Vallee (centre right, with his Dallas Buyers Club stars) broke though with his 2005 Quebec film, C.R.A.Z.Y.

Undeniably, English Canadian films are unable to compete with Hollywood in terms of all the great talents who live and work there, says Evans. Nevertheless, most English Canadian films also prioritize commercial success, and end up paling in comparison to Hollywood pieces. “That really creates a problem too — if your film looks like a pale version of a Hollywood hit, it shows that even though we are an English milieu, we cannot create something that is as enticing as the Hollywood product,” Evans says.

A case in point is Canada’s 2001 film Picture Claire. Under the respected Canadian director Bruce McDonald, the film starred Juliette Lewis as Claire, a Montreal woman who has to move to Toronto. Upon her arrival, Toronto police mistake Claire for a murderer. She cannot defend herself properly because she cannot speak English, and a game of cat and mouse ensues while the real murderer is at large. Despite a Hollywood presence in the film (it also starred Mickey Rourke), the dark comedy/thriller was so poorly received that it couldn’t even secure distribution and went straight to DVD; McDonald even released a 2002 documentary called Claire’s Hat: The Unmaking of a Film Plot, which included scenes cut from the movie. The documentary featured McDonald’s commentary and his explanation for the film’s failure, citing the confusing plot as one reason. Although mistaken-identity thrillers are typically well received (Lucky Number Slevin and Eagle Eye, for instance), this English Canadian one fell short.

Evans maintains that, unlike Quebec cinema, English Canada seems satisfied to produce film scripts that are second rate (a few significant exceptions aside): “And if you don’t have a good script, the film is not going to take off.”

This is not to say that English Canadians are unskilled. Evans says that many English Canadian filmmakers are “tremendously talented. But if you’re making a film that doesn’t have links — either in terms of the scripts, in terms of the money you’re investing in the film, in terms of what it is you hope to achieve — it will not take off.”

Quebec’s road to Oscar

“People around the world are looking at Quebec cinema now and waiting for the next director to come out of here. This has a tremendous impact on a country’s recognition outside of its borders,” said Rebelle director Kim Nguyen in a 2013 National Post article. And while Quebec filmmakers may be highly successful in their home base, researcher Loiselle argues that it’s only natural for them to be taking the logical next step: competing directly with English-language Hollywood films. This involves bigger budgets, A-list stars and collaborations with the best of the best.

Prominent examples include Denis Villeneuve, whose critically acclaimed and Oscar-nominated Incendies established him as a Hollywood player. His 2013 film Prisoners, about two families torn apart when their young daughters go missing, saw him collaborate with Hollywood heavy-hitters and Oscar favourites like Hugh Jackman, Jake Gyllenhall, Melissa Leo, and Mark Wahlberg (who served as an executive producer). The film has grossed $113 million as of February 2014 and has been nominated for a Best Cinematography Oscar. Meanwhile, Jean Marc Vallée’s Dallas Buyers Club, starring Matthew McConaughey as a Texas man with AIDS in the 1980s, has won an avalanche of praise, with Oscar nominations that include Best Picture, Best Actor, and Best Supporting Actor (Jared Leto), and Best Editing.

Canada will find out just how close this country is to Oscar when the Academy Awards air on March 2. With Dallas Buyers Club and Prisoners in the running, Canadian filmmakers — or actually, Quebec filmmakers — will be seen on the world stage. But can they bring home the gold?

Home-page photo courtesy of Flickr user Dave_B_ .

And the award goes to...

Dallas Buyers Club's Oscar nominations:

• Best Actor, Matthew McConaughey

• Best Supporting Actor, Jared Leto

• Best Picture

• Best Film Editing

• Best Writing

Matthew McConaughey and Leto also won the 2014 Golden Globe Awards for Best Actor and Best Supporting Actor, respectively.

Prisoners Oscar Nominations:

• Academy Award nomination for Best Cinematography