When elected officials and community advocates gathered Monday at Ottawa City Hall to call attention to violence against women, the purple scarves and ribbons many wore contrasted noticeably against the bright teal walls of Mayor Mark Sutcliffe’s boardroom.

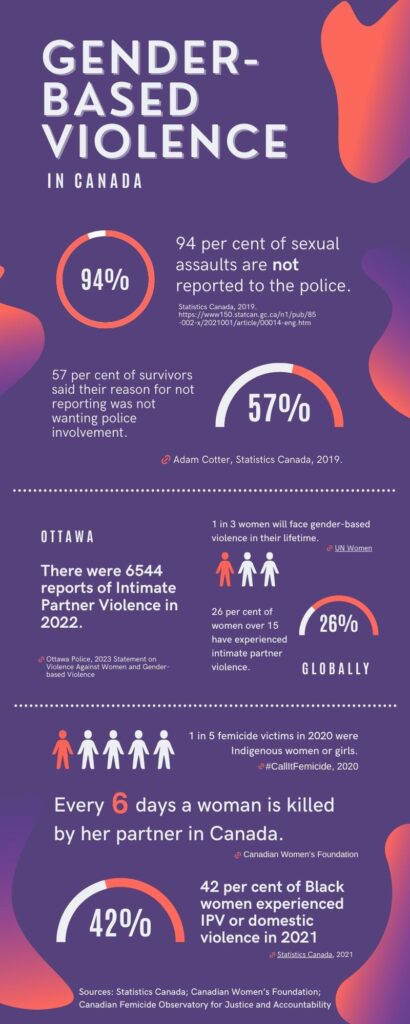

“One in three women will face gender-based violence in their lifetime,” Sutcliffe told the audience of city councillors, MPs and advocates, who had been invited to witness the signing of an official declaration marking 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence, an annual campaign lasting from Nov. 25 to Dec. 10.

Ottawa City Council previously declared intimate partner violence an epidemic on International Women’s Day back in March, following a recommendation that came out of an inquiry that investigated the deaths of three women who were killed in the Ottawa Valley in 2015.

Meanwhile, in the past 12 months, at least 62 women in Ontario were victims of femicide, according to a report from the Ontario Association of Interval and Transition Houses. This means, on average, one woman has been killed in Ontario every five days since November 2022. The report does not account for unreported deaths and disappearances.

Monday’s event in the mayor’s office came weeks after city council announced its 2024 draft budget, which includes a $13.4-million increase to the Ottawa police. In fact, council will vote on the budget on Dec. 6, the 34th anniversary of the Montreal Massacre, in which 14 women were killed at l’École Polytechnique.

Gender-based violence is a critical issue in Ottawa, Ontario and globally. With community members and organizations working tirelessly in the fight against sexual violence, some criticize the substantial increase to police funding. In a time when intimate partner violence is an epidemic, advocates instead are calling for culturally appropriate response initiatives, early intervention and a critical look into the systemic issues behind these acts.

‘Much more we need to do’: Sutcliffe

Here in Ottawa, there have been 5,815 reports of intimate partner violence in 2023 so far, compared to 6,544 in 2022 and 6,385 in 2021.

Insp. Peter Jupp, a specialized investigator for the Ottawa police, said the current statistic does not mean there is less domestic violence. “There’s so many things that can impact reporting,” he added.

Jupp explained one of the OPS’s biggest problems is people not reporting due to lack of faith in the authorities. He said the force is currently working on a new strategic plan that specifically addresses domestic violence.

“We’re consistently told from our community and advocacy groups that domestic violence is one of our biggest community concerns,” he said, pointing out the importance of working with advocates.

In his comments during Monday’s event, Mayor Sutcliffe said the increasing rate of gender-based violence in Ottawa was a priority in hiring new police officers. “We know there is so much more we need to do.”

The 2024 budget draft proposes a hiring of 555 new police officers and civilian employees over the next three years.

Ottawa Coalition to End Violence Against Women publicly critiqued the funding increase, calling for more funding to community-based initiatives, affordable housing, transit and immigration support.

Prevention must address root causes

Other advocates say more work needs to be done to prevent gender-based violence instead of relying on a police response.

“Police don’t prevent anything, they react,” said Marlihan Lopez, an activist and expert who worked on the development of the National Action Plan to End Gender-Based Violence. “The first thing is deconstructing what prevention is and the idea that police prevent violence.”

Lopez said prevention looks like “addressing the root causes of gender-based violence,” like intergenerational trauma. “Our communities need a lot of healing,” she said. She noted a way of prevention is having access to mental health and resources that help engage healing while acknowledging cultural and historical factors.

Lopez also mentioned the importance of youth and how, by enforcing their agency, they can be empowered to interrupt violence.

“If you go to a youth that comes from a racialized background and you tell them their culture enforces less women’s rights or is more misogynistic, that’s not going to empower them to interrupt violence,” Lopez explained.

Alexandra Bishop, a social worker with CALAS de l’Outaouais, expressed a similar sentiment, pointing out how education and early intervention is necessary for prevention.

CALAS de l’Outaouais is a non-profit organization fighting against sexual violence in Ottawa-Gatineau. Bishop said her organization educates secondary and mature students, social workers and police to ensure everyone knows what sexual violence is and how to prevent it.

“Every student, every person should have the same content,” she said, pointing out the importance of consistency in education.

She said CALAS is working towards more wide-scale events to get the message across. Recently in September, CALAS co-hosted the Take Back the Night March, an annual action encouraging people to stand against sexual violence.

“A lot of prevention is necessary,” she pointed out.

Meanwhile, the Ottawa Rape Crisis Centre is providing over 500 survivors of sexual violence with crucial supports, according to service navigator Caron Cuff.

Cuff said the organization is trying to be as preventive as possible but mostly works with survivors. “Our role is to support them as an individual through counselling, access to safe accommodation, basic needs,” she explained.

She said a lot of clients choose not to report to the police and instead seek support in the community.

Cuff said healing looks different for everyone. “We support whatever that individual’s perspective of healing looks like in any capacity that we can.”

She noted some survivors do wish to report to see a measure of accountability, but for some, it’s not that important. Cuff noted sometimes the perspective changes, depending on where someone is in the healing process.

According to Statistics Canada, 94 per cent of sexual assaults are not reported to the police. Fifty-seven per cent of sexual assault survivors said their primary reason for not reporting was not wanting to involve the police or the criminal justice system.

Jupp said the mandatory charging guidelines in Ontario, established in 1999, do not allow police to suggest a non-criminal resolution to incidents of domestic violence.

Police-alternative approaches needed

Those advocating against gender-based violence are asking for more non-police involved approaches to intervention and response.

For Lopez, responding to gender-based violence looks like equipping survivors with what they need to leave violent situations, like urgent financial support, secured Canadian citizen status and secure housing. Lopez said transformative prevention involves addressing the systemic issues that allow for gender-based violence to occur.

“The only response that governments really are invested in are responses through the criminal legal system, which does not prove to reduce or address gender-based violence, and according to most survivors, do not provide healing that they need,” she explained.

When it comes to restorative justice, Indigenous leaders are looking to return to the original teachings.

Carol McBride is the president of the Native Women’s Association of Canada. She said getting back to a “cultural approach” of serving justice is important to renewing law enforcement’s credibility.

“Indigenous people are overrepresented in police-involving death. That’s serious,” McBride explained. “Indigenous people represent one third of people shot to death by police. There’s definitely something wrong there.”

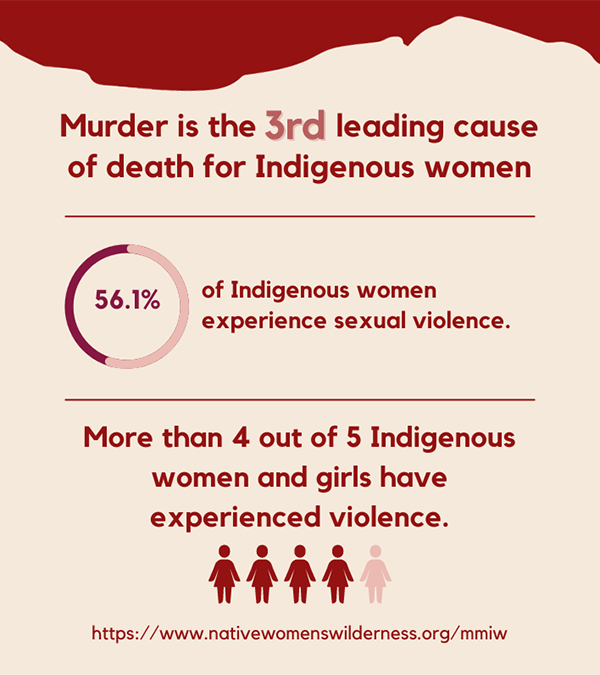

Murder is the third leading cause of death for Indigenous women, with more than four out of five Indigenous women and girls experiencing sexual violence in their lifetime.

McBride said restorative justice looks different for each community. “We have not been at the same level of trauma, of cultural shock or identity,” she said. “On an Indigenous level, lawmakers need to engage in a meaningful and collaborative discussion with the community they serve.”

She mentioned there is money allocated to develop a legislative framework for First Nations policing. She said she hopes the discussions reflect the community they serve and are culturally- and trauma-informed.

“I think that they have a long way to go,” McBride added. “I’m feeling hopeful.”

McBride said communities must be actively involved in the discussions to ensure they receive appropriate services.

“I’m a grandmother and I have four grandchildren that are growing up,” McBride said. She added she “wouldn’t want them to go through a lot of the discrimination” brought on by assimilation and settler-based approaches in the criminal-justice system.

A vigil for The National Day of Remembrance and Action on Violence Against Women in remembrance of the l’École Polytechnique massacre will be held in Minto Park on Dec. 6.