They loom in downtown areas, veering on obsolete. Once bustling, entire storeys now sit quietly vacant, abandoned by workers and employers who favour hybrid and home offices. Below-capacity office towers across the country are increasingly being considered for conversion to infuse more housing in downtown areas. Ottawa is no exception.

Experts deem Ottawa particularly poised for conversions, with ten federal government buildings actively being considered for disposal. In early November, the federal government announced three of its former office buildings in central Ottawa will be converted into housing units.

City council approved recommendations to incentivize office-to-housing conversions on Nov. 8, anticipating future similar plans. These projects seem attractive on paper, but unique case-by-case considerations often make or break their financial viability. Industry insiders say the measures passed by city council are far from enough to convince developers to take on expensive renovations. As the city looks to increase the housing supply, office-to-residential conversions offer a niche solution rather than a panacea, advocates say.

City council evaluated what conversion incentives it could offer in light of the housing need and the availability of office buildings, according to Coun. Jeff Leiper. “We’re in a housing crisis,” he said. “There is not enough housing for everybody in Ottawa.”

The city pledged to create 151,000 new housing units over the next 10 years. Conversions are one way of building “more housing more quickly” in a “more sustainable way,” Leiper said.

Converting buildings produces a much smaller carbon footprint than re-building from scratch, as renovations saves the concrete, a CO2-heavy material, in the existing building structure.

The approved incentive measures target conversions where no new storeys or major additions are proposed. Qualifying projects could potentially save over $50,000 in fees and benefit from reduced processing time when applying for building permits.

Leiper said these measures are all that city council is planning to offer. “There isn’t a thrust to go further.”

Leiper said he expects market forces to guide developers to turn underused office space into housing sooner or later, though demolition and re-building from scratch may prove more popular than conversion for buildings with outdated infrastructure.

The city’s incentives are likely too small to entice developers to go through with conversions, according to Dean Karakasis, executive director and CEO of the Building Owners and Managers Association Ottawa.

“You’re talking about million-dollar projects. What is $56,000 relative to that?” Karakasis said. “Your architecture alone will easily eat that up.”

New recommendations to remove red tape, such as a zoning amendment to push certain proposals through faster, are not game changers either, he added. “We’d like to see the city offer a better fast track if they really want buildings to convert,” Karakasis said.

It would take some extraordinary measures to incentivize mass conversions. In many cases, they aren’t as attractive as the buzz may suggest, Karakasis said.

If a building is paid off, keeping a partially vacant office may be more profitable than a complete, costly renovation. “It isn’t just because the building is technically capable of converting that it’s a logical candidate,” Karakasis said. “It’s all about the money.”

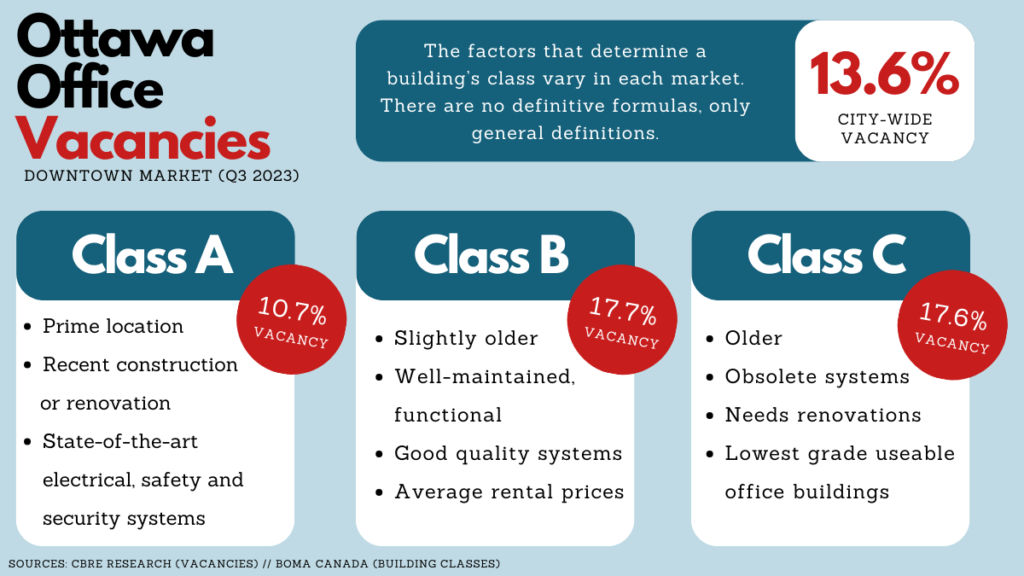

New buildings are cheaper to renovate, but often, it’s 50-year old buildings being considered for conversion efforts. Those buildings fall under class C, a designation that involves extra conversion costs.

As with any conversion, their layouts need to be adapted to housing needs, but they also need to be brought up to current building code standards according to Ian Lee, associate professor of management at Carleton University.

“A lot of these C buildings are tear-downs,” he said. “Because it’s not worth the cost.”

Every building is unique so, for some, conversion makes more sense. District Realty converted the former Red Cross offices at 170 Metcalfe St. in 2018. The building, now a luxury apartment complex bearing amenities such as a theatre room and a fitness centre, used to be “somewhere in between” class B or C, according to CEO Jason Shinder.

The cost of the Metcalfe project was comparable to re-building from scratch, Shinder said, noting that in some cases, re-building can be cheaper than conversion. “It just becomes a little bit faster, a little bit better for the environment.”

“The rent for apartments in Sandy Hill would be greater than the rent for office space in Sandy Hill,” he said, explaining which buildings make good targets. “If you already own the building, and it’s going to be fully empty or almost empty, or you’re struggling to find commercial tenants for it, then it’s probably a good candidate to be an apartment building.”

Nevertheless, elements like floor plans, plumbing and windows can render an empty a building too complicated or expensive to retrofit.

For the amount of subsidies needed to make some trickier class C buildings viable for conversion, Karakasis said all three levels of government — federal, provincial and municipal — would need to pitch in. Yet, on a country-wide scale, those efforts would not be viable either, Lee explained. “It will run into the hundreds of billions of dollars, because there’s so many buildings.”

That’s without the cost to put renovated units on the market at affordable housing prices.

For housing to be considered affordable, rent needs to sit at or below the average market rent for similar units in the area. That’s $1,347 a month for a one-bedroom apartment in Ottawa.

“Developers just can’t make housing truly affordable and make profit on it, especially in the current market conditions,” said Brandon Bay, board chair of Make Housing Affordable, an Ottawa-based advocacy group. He cited the elevated cost of construction as a defining factor of the problem. “It needs to be levels of government leading.”

As the federal government evaluates selling off some of its vacant properties, proponents have high hopes for more residential conversions. However, Bay said the effort to offer financial incentives has been lacking.

He said the government is not showing enough leadership in discounting their vacant buildings to sell them to developers, or in funding their conversion into affordable housing “like they ought to be.”

Lee said policies likely to help with affordable housing include rent subsidies directly to consumers or increasing government-owned housing. In contrast to private development, the latter is funded through taxation as opposed to being profit-oriented.

The city estimates there are over 10,000 people on the social housing waitlist, with wait times exceeding five years in some cases. “We’re not moving fast enough to clear that up,” Bay said.