The grazer effect

By Nadiah Sakurai

In 2011, scientists at the University of British Columbia fastened four different groups of steel metal plates to a section of shoreline near Vancouver where tidal waters washes over them and receded again day after day.

The plates were of special design – two groups consisted of black coloured plates and the other two were made up of white colored plates. The black plates warmed the plates up more than the white plates due to it absorbing more light.This was done to simulate the warmer ocean that is expected due to the influence of climate change.

This resulted in one group having less biodiversity than the others. One group of the black plates was all green – covered just in seaweed.

The others were bustling with more marine creatures – barnacles (crustacean animals which look like shells), baby snails, red algae and small critters such as amphipods (which has brown-black shrimp-like bodies). The reason why the one group of black plates looked different was because of one herbivore creature – the limpets. The warming plate covered only in seaweed had no limpets and the increase in temperature resulted in seaweeds taking over the plate.

What the scientist found was fascinating and not easily predicted.

The plates were part of an experiment to see how the ecosystem as a whole would respond to climate warming – if they would respond differently depending on the presence of limpets. The result showed ecosystems without the limpets would suffer in terms of biodiversity when the temperature rose.

“Consumers like these limpets are very important in this system, they facilitate (or help) other species… If important consumers like these are lost, the ecosystem is more likely to be harmed by a warming climate,” Rebecca Kordas from Imperial College London, the lead author of the study said.

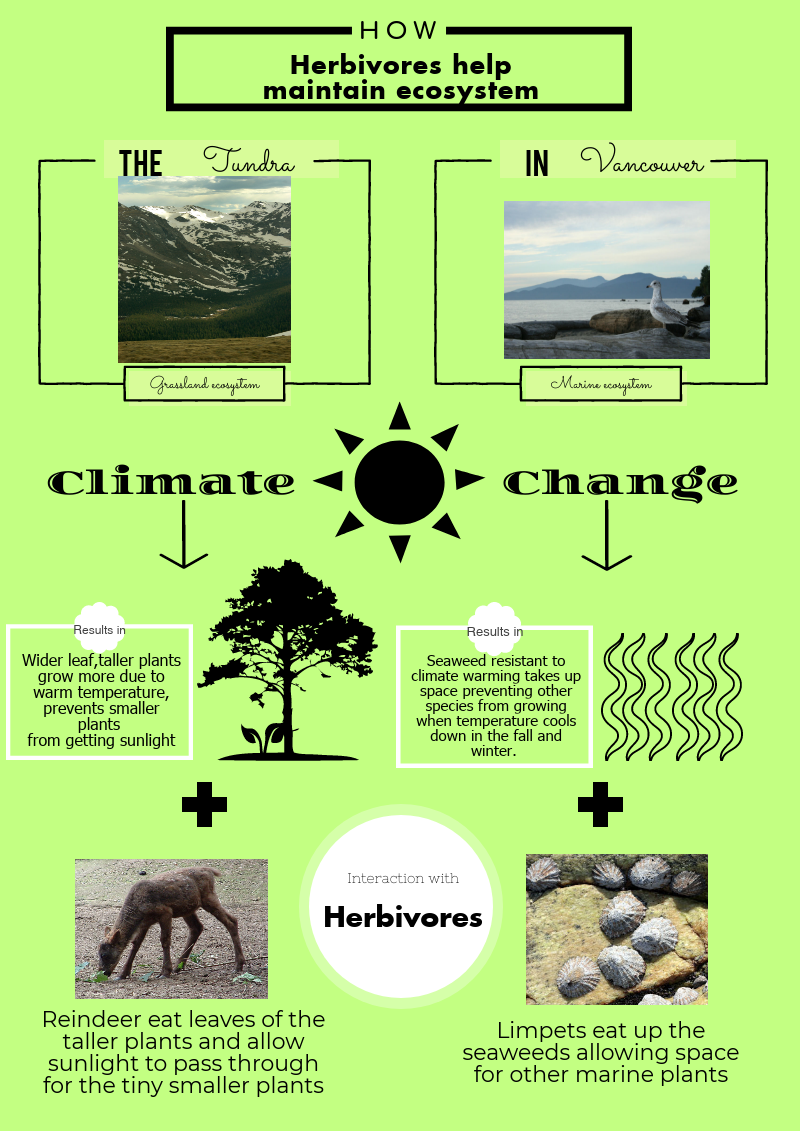

The experiment is one of many studies done by scientists to understand the relationship between herbivores and plants under the pressure of climate change. In the Tundra, a study experimented whether biodiversity declined when there were no reindeers to graze the field during climate warming. Another study done in the Arctic examined how plant biodiversity would fare without the presence of herbivores during temperature warming. In both studies, the result showed the sites without the herbivores loss plant biodiversity.

In the tundra, biodiversity was lost in the sites without reindeer as climate warming enhanced the growth of the taller plants with wider leafs – preventing the smaller tundra plants from getting sunlight.

Elina Kaarlejarvi, researcher from Umea University who studied the tundra, said the results could be applied in the bigger picture.

“We have good reasons to believe that these results would hold also in a wider scale, since warming is typically enhancing plant growth and herbivores consume plants.” – Elina Kaarlejarvi

This is because of how the taller plants crowd out the smaller plants by blocking sunlight from them.

If climate warming enhances plant growth, would that not be good for biodiversity? The answer to this is no. This is because climate warming effect different plants differently.

Michael Loik is a researcher at the University of Califonia who studies the effect climate change has on plants.

“Some species might move into certain places because of slight change in temperature making it somewhat more conducive in their survival in the new habitats,” he said. Meanwhile others might be outright pushed towards extinction.

“At any one particular place, there is bound to be winners and losers when it comes to biodiversity,” Loik said on the effect of climate change on biodiversity.

Herbivores help to prevent the effect of climate change on these plants – winners or losers – from disrupting the ecosystem and the biodiversity.

“Every organism plays an important role in an ecosystem,” Kordas said. “Consumers (herbivores and predators) are important because they keep the populations of the species they eat ‘in check’ – they keep them from taking over all of the resources.” They make sure that the “winners” don’t take up too much space which could result in the decline in biodiversity.

In Vancouver, the study was motivated by wanting to understand just how important interactions between organisms were.

“I’ve always been interested in how these links between species change with temperature but by looking at it all together and not just individually,” Kordas said.

“I wanted to understand how the species interactions were changing specifically and that’s why I did the added treatment of changing whether limpets were present or not so I could get the idea of how temperature was effecting the interactions.”

They play an important role in the ecosystem, Kordas said. “Without the limpets, the seaweeds take over the whole system because it grows really fast, it takes up space really fast and basically crowds out the barnacles. “

The limpets eat the seaweeds and by doing that creates a lot of space, allowing barnacles space to feed, and settle in to grow and become a bigger population.

Allowing barnacles to grow keeps the intertidal ecosystem diverse.

“Barnacles are very important to rocky intertidal ecosystems because they provide a lot of structure that is useful for other organisms. (Their presence) support a bunch of other species – creating more diverse and complex habitats.”

In the experiment, the plates that were warmed up with no limpets on them resulted in less biodiversity than the plates (not warmed) with no limpets.

This was because of how climate warming effected the seaweeds and the barnacles differently.

Limpets are found all over the world. They are small creatures – around one to one and a half inches long; related to snails and have shells on their back.

“They are very hard to remove from the rocks because they have an amazing ability to clamp down against the rock to avoid being eaten and to retain water within the shell when the tide is low,” Kordas explained.

“If you go out to the shore, you’ll see barnacles everywhere so there is this kind of idea that barnacles are like the cockroaches of the ocean and they will survive no matter what. But they are actually kind of sensitive to temperature,” Kordas explained.

Barnacles are not able to stand high temperatures and when the temperature spiked up to 40 degrees in the summer, it resulted in lots of deaths for barnacles.

The seaweeds on the plate on the other hand were less effected by temperature than barnacles.

“The seaweeds found on the warming plate were weedy species that are responsive to heat, so the seaweed on the plates were less effected by the temperature than the barnacles,” Kordas said.

This meant less competition for the seaweeds during the time when the temperature were warm – like in the summer. As there are no limpets to munch on them, they flourish on the plates and take up all the space – so when the temperature is cooler in the fall and winter, the barnacles are not able to find space to grow in and the biodiversity in the ecosystem declines.

This is how herbivores (the limpets) in the case of Vancouver help sustain the biodiversity of the ecosystem during climate warming. Kordas says the result shows the importance of maintaining the ecosystems.

“It is quite likely that similar results will be found in other systems.” – Rebecca Kordas

In the Tundra, another study was done to see the relationship between climate change and herbivore-plant interaction. The experiment took place for five years. The study took 56 plots in the tundra as part of the experiment. Out of these plots, 28 were fenced individually to prevent the reindeer from entering.

The biodiversity of the area were measured by comparing the amount of plants in the area in 2009 between July and August when biodiversity was most abundant and compared it to the amounts of plants in the area in 2014 (between July and August).

“Climate warming is boosting plant growth, while reindeer are eating plants,” Kaarlejarvi said in an email interview. “What happens to the plant diversity in the areas that are grazed compared to areas that are not grazed?” This was the motivation behind the study according to Kaarlejarvi.

The study result showed areas with reindeer maintained biodiversity in the tundra during climate warming. “We found that without reindeer grazing tundra plant diversity would decline under climate warming, while in presence of reindeer warming can increase species richness,” she said.

This is again due to how there are winners and losers in climate change. In the case of the tundra, the winners are the taller and wider-leaf plants in the tundra. They respond to climate change by growing rapidly.

The losers are the smaller tundra plants. As the taller plants grow more rapidly, they grow more leafs, shading the tiny tundra plants and preventing them from getting sunlight.

Reindeer helps this situation by eating the leaves of the taller plants and providing spaces for the smaller plants to get sunlight and grow in.

“Reindeer keep vegetation low and that way gives possibility for small and slowly growing plants to benefit from warmer climate and exist in a plant community,” Kaarlejarvi said.

“We can protect tundra plant diversity by protecting mammalian herbivores, especially reindeer populations,” she said.

Even though climate change effect plants differently, biodiversity of an ecosystem can be kept balanced and maintained by having their ecosystem intact – making sure there are consumers to keep the plants in control.

“We see loads of examples about (importance of intact ecosystem) in other experiments as well. We see a massive effect on the rest of the communities (when one part of the ecosystem is taken out).”

Now scientists knows how warming effects whole communities. “The next thing is to understand how this happens and why this happens,” Kordas said. “We might know how diversity changes with warming but we don’t really at all know why any of it happens.”

Kordas is now studying the relationship between prey and predators in the warming climate in Iceland to further understand how intact ecosystems are impportant.

“Intact communities are really important for the health of the world,” Kordas said.