The illusion of control

PTSD plagues more than a fifth of cancer patients within six months of diagnosis -- but is Ontario doing enough to help?By Patrick Barrios and Kat Topinka

Sindy Hooper thought she had gallstones.

She was experiencing a few vague symptoms, including itchy skin, fatigue, and weight loss. But a long ultrasound at The Ottawa Hospital revealed that she had a malignant tumour in her pancreas, about an inch in height and width: pancreatic cancer.

“I was facing dying within six months,” says Hooper, remembering the cold January day when she was diagnosed with the cancer. “It was very, very, very frightening.”

After a CT scan confirmed the diagnosis, Hooper underwent an eight-hour Whipple surgery, during which surgeons removed half her pancreas, half her stomach, her gall bladder, and part of her small intestine. This was followed by 18 rounds of chemotherapy and a month of radiation therapy.

It’s now been over five years since Hooper’s diagnosis, a milestone only seven per cent of those with pancreatic cancer reach. But a cancer diagnosis often has a long, lingering impact on a life, and for those with pancreatic cancer, the threat is never really gone.

Hooper is still called in every six months for a CT scan to check whether the cancer has returned, a process that will continue for the rest of her life. If it does return, not much can be done, she says. Another surgery is not possible, and chemotherapy alone will only be able to prolong life by a few months, at best.

Photo by John Hooper, used with permission

“When you get diagnosed with something like this – I mean, it’s a death sentence,” says Hooper, her voice breaking. “I literally live my life in six-month intervals. I don’t plan for anything beyond six months. Even now.”

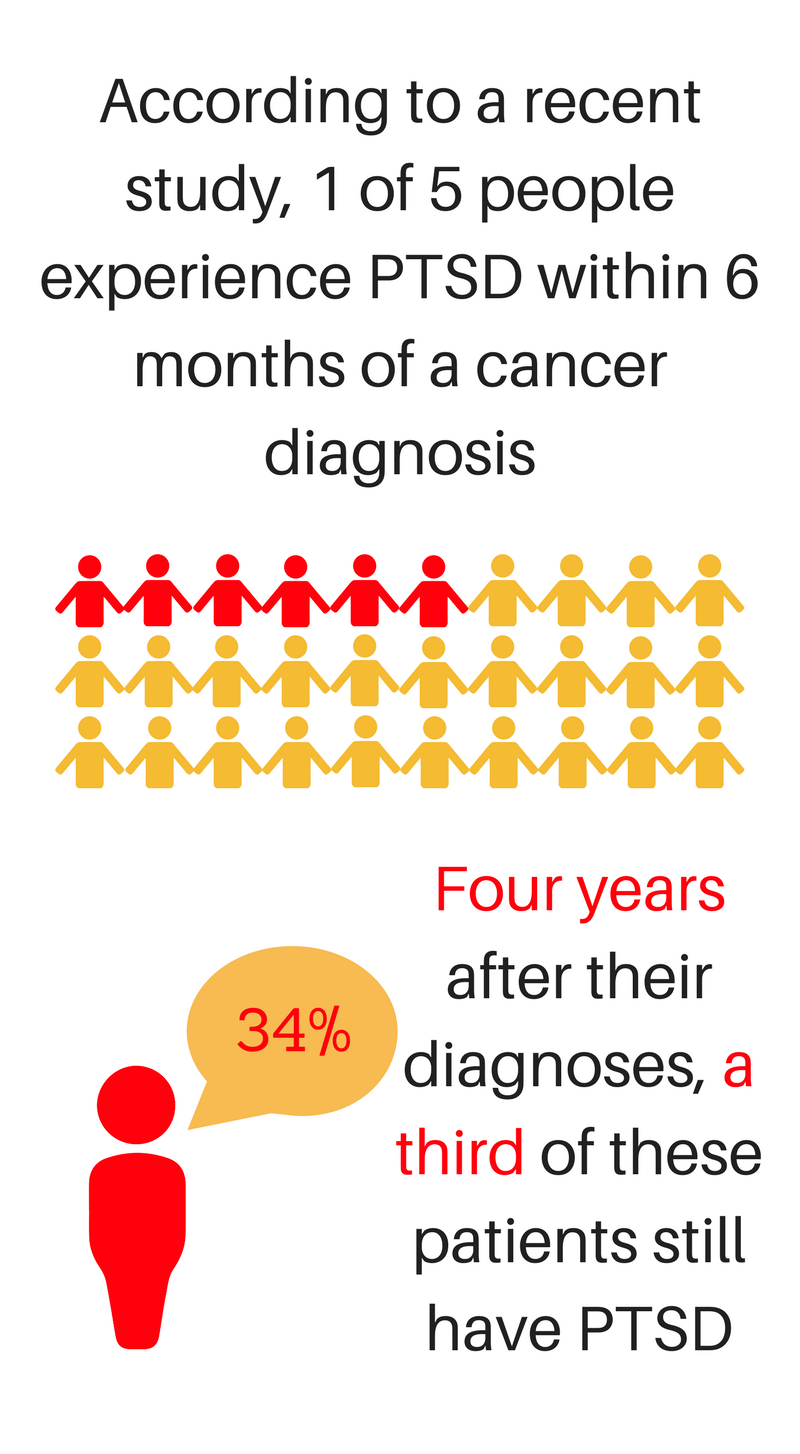

Receiving a cancer diagnosis, for any form or severity of cancer, can be a harrowing emotional and psychological experience. In fact, 22 per cent of cancer patients experience symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder within six months of their diagnoses, and these symptoms can persist for years, according to a study by researchers at the National University of Malaysia, published late last year in Cancer, the American Cancer Association’s official journal.

“We conducted this study because there is need to better understand and address the emotional repercussions that many patients with cancer face,” says psycho-oncology researcher Caryn Chan, lead author of the Malaysian study. “This understanding is important, because the health care system has a long way to go in terms of supporting individuals not just after a cancer diagnosis, but after their treatment ends.”

Flashbacks and nightmares

PTSD was officially recognized as a diagnosis in 1980, when it was added to the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders. At the time, the condition was mostly associated with war and combat, but it can be linked to any traumatic event.

Unlike most existing studies examining cancer-related PTSD, which rely on questionnaires, feature small sample sizes, and analyze cross-sectional data, Chan says her team used structured clinical interviews and tracked various patients over four years, to give a better idea of the long-term course of PTSD. The study followed 469 patients, though this number dwindled to 245 by the four-year mark, due to patients dying or dropping out of the study.

Now, patient groups and care providers are raising questions about whether there are enough measures in place to address the residual effects of these rigors, such as post-traumatic stress disorder. An improved system could increase awareness of PTSD among those diagnosed with cancer and widen availability of specialized care to address it.

According to the National Centre for PTSD, symptoms of PTSD include intrusive thoughts and flashbacks, nightmares, anxiety, a reduced attention span, and an urge to avoid anything that reminds you of the particular events which caused the PTSD. Cheryl Harris, the only psychologist assigned to The Ottawa Hospital’s Psychosocial Oncology Program, says the issue of avoidance is particularly problematic for cancer patients.

“If someone is distressed to the point of avoiding reminders of cancer, it can lead them to avoid the hospital,” says Harris. “I have met patients like this, where they very much struggle with coming in for follow-ups, and they have significant fear of having future MRI scans or anything that could identify the potential progression or recurrence of cancer.”

Another issue is that many patients might experience symptoms of PTSD without recognizing them or mentioning them to experts.

“I never really thought of [these symptoms] in terms of PTSD, but absolutely,” says Hooper. “I mean, the number of nights where I can’t fall asleep. The number of nights where I wake up in the middle of the night, and then I’m awake for hours, because I’m thinking about all this horrible stuff. Even during the day, it’s difficult to focus sometimes.”

According to Harris, there are two main types of psychological rigours that can accompany a cancer diagnosis.

The first is the psychological effect from physical changes associated with treatment, ranging from overwhelming fatigue to body-image anxieties related to treatment. These anxieties can be amplified when what’s lost – such as a breast removed for a mastectomy – is important to someone’s sense of identity.

Then, there are the existential crises that are thrust upon patients with potentially life-threatening illnesses; the confrontation with their own mortality and with the fears that surround death, in what Harris terms as the realization of the “illusion of control.”

“Life can change in an instant. I feel that patients are well aware of this, and it can be frightening for them, because they feel particularly vulnerable,” says Harris. “They can grapple with questions about the randomness and unfairness in the world, the fact that bad things do happen to really good people, and they’re left with fear about the cancer progressing or recurring.”

Changing the narrative

Harris says medical experts need to identify symptoms of PTSD as early as possible, so that psychological interventions can be put in place to help patients “live the best way possible” with their cancer.

“Patients with cancer and survivors who recognise symptoms of PTSD in themselves … should not wait for symptoms to go away on their own,” agrees Chan, noting that her study shows symptoms of PTSD can last for over four years. “Many of these symptoms can be resolved much more quickly – often within weeks or months – with professional support and therapy.”

How to Support a Loved One: Dr Cheryl Harris

But Jaymee Maghop, the public policy assistant at the Canadian Cancer Survivor Network, says that access to such services across Ontario is inconsistent and inadequate.

“I think the root problem with the lack of after-care services is that it isn’t recognized as part of the normal cancer care continuum,” says Maghop, who points out that while rehabilitation services exist during cancer treatment, patients are often left to deal with things like PTSD on their own once treatment comes to an end.

“Some survivors don’t even realize that there are post-treatment options out there, and that they should be seeking these,” says Maghop. She adds that even if patients do ask for referrals to rehabilitation services, their oncologists can be hesitant to give them recommendations based on their own unfamiliarity with available services. In Maghop’s eyes, the current lack of services for cancer rehab “isn’t just an Ottawa or Ontario problem” — it’s a nationwide issue.

Harris argues that there are good services already in place, but more funding and a long-term strategy are needed to expand the services currently available.

“The services provided here at The Ottawa Hospital are a good start … But is one psychologist for all cancer patients within the Champlain region [a region stretching from Pembroke to Hawkesbury] appropriate? Probably not,” says Harris.

One practice that Harris supports, which has been rolled out to cancer centres across Ontario over the last couple years, is an electronic screening measure filled by patients as they enter waiting rooms.

Patients rate their symptoms on a 10-point scale. Most are physical, like pain, nausea, and lack of appetite, but the list also includes anxiety and depression. These results are printed out and provided to their health-care professional, helping them identify trends that could indicate that a patient might benefit from a referral to a psychosocial specialist.

Beyond surviving

On the flip-side of the potentially PTSD-causing rigours of a cancer diagnosis is what many are calling post-traumatic growth.

“[PTG] refers to a situation where patients describe changes that happen such that they learn to live a more intentional and meaningful life following their diagnosis,” says Harris.

While research is not conclusive regarding a link between PTG and cancer diagnoses, Harris says there is “a lot of hope of people being able to cope well, but we need to help them to be able to do that.”

One survivor who may have experienced some degree of PTG is Hooper, who has completed several marathons and Ironman competitions in the five years since her diagnosis, raising awareness and over $200,000 for cancer research and The Ottawa Hospital.

When Hooper was diagnosed, she spent months seeking out long-term survivors of pancreatic cancer. In five years, she says she’s only met two people who survived for more than a year – and this terrified her. She wanted to find a beacon of hope, someone she could point to and say, “You see? There’s a chance!”

Now, Hooper says her goal is to be that beacon to others looking for hope. She wants to remind everyone – not just survivors – to live in the moment and make the most of every day.

And to anyone struggling to cope with a diagnosis, she says to stay as hopeful as possible.

“If you hope, there’s less fear,” says Hooper. “And it’s a little bit easier to live with hope than with fear.”