‘Screw the rules’

saving lives on the front lines of harm reduction in Ottawa

By Emily Fearon

Marilou Gagnon wasn’t surprised when her passions made her an activist. She says she loves being called a rebel, but as long as that doesn’t mean she’s incompetent, disorganized or dangerous.

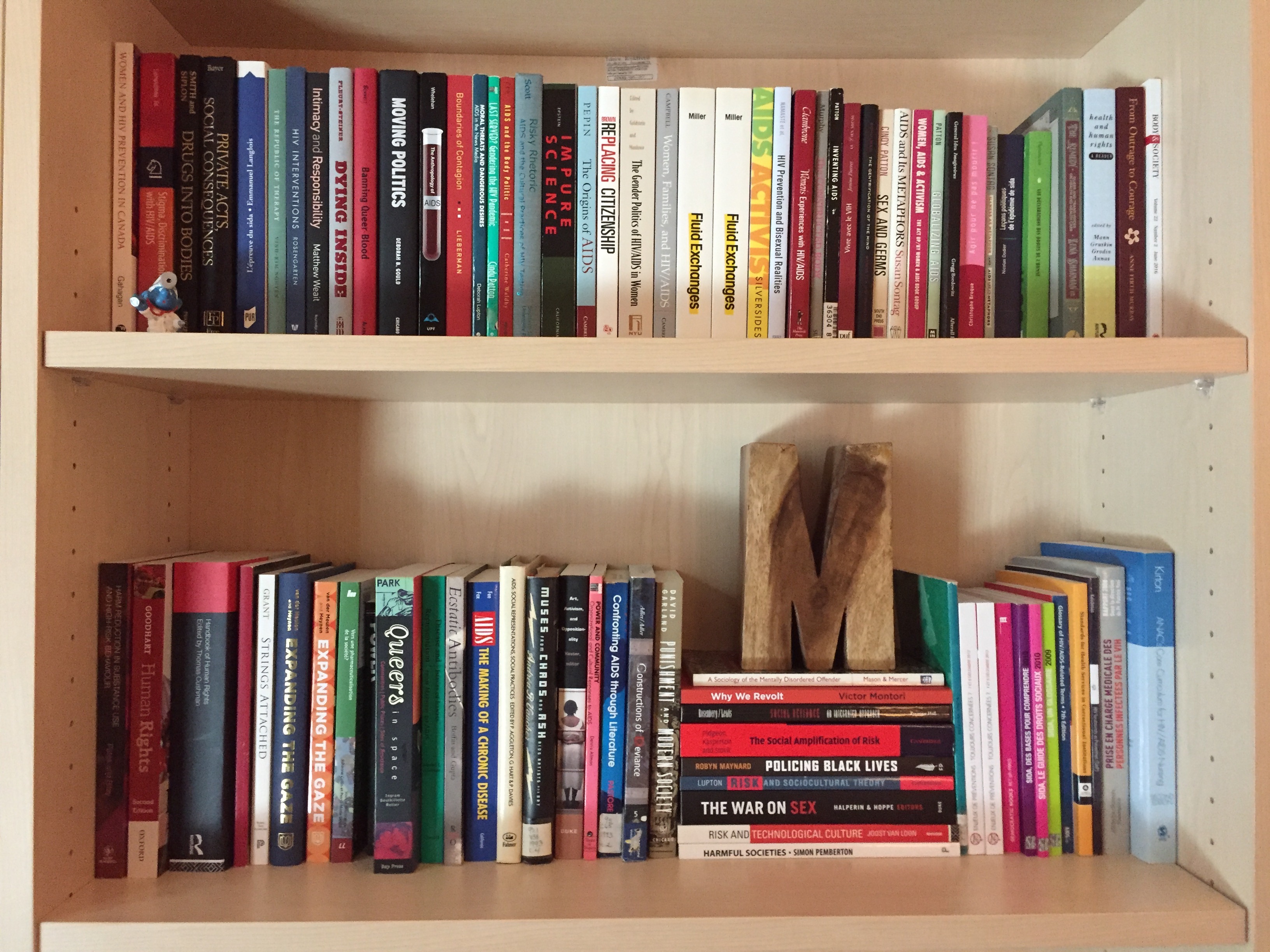

Even while in the process of a big move out-of-province, Gagnon’s office at the University of Ottawa is tidy and in order. She apologizes for the mess, nonetheless. Her space in the school of medicine has walls covered in colourful books, posters and paintings. Gagnon is a nurse but is also a doctor since she pursued a PhD, though she says that was never part of her original plan. In fact, she landed at the U of O for her doctoral studies and has now been in Ottawa for 12 years. She moved to the Capital from Quebec; born in a small town outside of Montreal, she didn’t learn to speak English until she was 18, but studied at John Abbott College in English anyway.

It was during her clinical rotation that her life was changed. “I went in an HIV clinic and everything happened right there,” she says.

While fascinated by the medical complexity of HIV, Gagnon says it was the social and political injustices and implications of the virus that sparked her passion for being an advocate for others’ rights.

“I didn’t know I had that in me,” she says, and asserts, “you could not be a nurse in HIV and not be involved in advocating for the rights of people living with HIV.”

Since her eureka moment Gagnon has hardly had a moment to breathe. “I think people from the outside often think that I don’t sleep because it is really seven days a week, nonstop,” she says.

“You couldn’t find somebody who’s more ethically grounded or devoted to her work and what she believes in,” says Jean-Daniel Jacob. He’s also a nurse and professor at the U of O and he and Gagnon completed their PhDs together. They’ve been close friends and coworkers since 2006. “When she worked in HIV, she lived it, she breathed it, it’s fantastic, and now same thing with all the work in harm reduction,” he says. “She’s definitely someone who will put her work into action.”

Gagnon’s projects include starting an official incorporated professional association for nurses working in harm reduction, starting a nursing observatory, she’s written 15 op-ed pieces in 2018 alone and “I also ran an overdose prevention site for 78 days in Ottawa with an amazing group of people, and I was the only nurse on the core organizing team,” she says nonchalantly.

Last year, from August 25 until the November cold made operation too difficult, Gagnon and other volunteers worked tirelessly in Raphael Brunet Park to ease the pain and horror of the opioid crisis. “Opening an overdose prevention site took us seven days and a few tents and tables and chairs and volunteers. It’s just that easy,” she says. But it was only the opening of the site that was simple. The investment and work the site demanded of its volunteers was anything but easy.

The moment Gagnon joined the team she had three days to train volunteers, find medical supplies, create protocols, pick a location and prepare for the response from the community, media and law enforcement. It was “a lot of emotions and stress and excitement in very few days, and then we opened.”

And she was there every day. As the nurse on staff in the injection tent, she would do three to four shifts a day. She says running the site was simple and it took only one week before the team hit their stride and could have expanded the site’s hours of operation. But they never did. Opposition from the community, a lack of support from the mayor’s office, other demands and dramas made it messy. She had a general sense that the site was supported by the community, but there was also a small group of vocal and vicious opponents of the site. Gagnon recounts days dealing with police calls, obstructions of their space, air horns, manure spread across the park’s lawn, and having to wear sunglasses at night because lights were used to blind the volunteers. But what surprised Gagnon was the media coverage.

“I thought I knew what to expect but the media coverage surprised me a bit in how bad it was,” she says. “I expected the police to be our biggest obstacle,” she continued, but it was the media’s lack of context or education that became a barrier and negative force in the public’s perception of the volunteers’ work. “The coverage was meant to be very divisive, like the poor neighbour victims, and the rebels.”

She did name one journalist, however, who covered the site well. Kieran Delamont, who wrote for Ottawa’s Metro paper before it folded at the beginning of 2018, was the first to cover the site.

In his most revealing interview with Gagnon while the site was open, Delamont says he could tell how exhausted she was. “It was somebody who was really tired but didn’t want to say they were tired . . . very accomplished fatigue, in a way. I remember her wearing her heart on her sleeve and being pretty honest about that and the toll it takes.”

Delamont, who used to cover City Hall but now freelances, called Gagnon a polarizing figure in local politics. “You could kind of see when she went to board of health meetings there was a little bit of ‘ugh here we go again’ kind of attitude,” he said. “But you need those kind of people who are going to be a constant thorn in the city’s side.”

While Delamont only knows Gagnon professionally, he said he could imagine the toll the site took on her. “Marilou said she knew the name of everybody that came in. That all the people who showed up to use their site, she was trying her best to remember everyone’s name,” he said. “It wasn’t a heartless, mechanical service as much as it was really just people watching out for one another in the community.”

The site eventually closed when Ottawa’s weather became too cold. Gagnon said this was a calculated move on the city’s behalf that she and her team would be edged out by the elements. “This was not a decision . . . we were forced to close because we didn’t have any other option,” she said. “To this day I cannot really understand how a responsible elected official can shut down something like that in the context of a crisis.”

Gagnon affirmed Delamont’s read on her. She said she was exhausted. But she also called working at the site the best experience of her life.

“It’s hard to summarize 78 days,” she says. “It’s a combination of being extremely proud and very emotional and really experiencing almost like you’re a part of a family . . . but at the same time being extremely angry all the time at the system; the systems that are failing people, the systems that have created this problem in the first place, and also how systems are creating these big barriers for us.”

She said it was hard to leave the people behind as the site closed — it was a sense of success amid the harsh circumstances that halted their work. “We actually saved people’s lives in there from overdoses, we helped them at the most vulnerable points, got to know them, hear their story, then just abandon them.”

While there is a Phase Two of this project coming down the line, Gagnon won’t be a part of it. She’s leaving the U of O to head to the University of Victoria. She’ll be in the same teaching role, but in a province pushing forward in overdose prevention at a much faster clip than Ontario.

Jacob says that Gagnon’s ability to combine academia and activism makes her a good fit for her new role. “Ottawa U is losing a gem,” he adds. “You don’t get a prof like that very often. You don’t get those types of prof really ever.”

In B.C. Gagnon will carry on her passionate work in the niche of rebellious harm reduction.

“Harm reduction was never a public health intervention, it came from people that were very grassroots and activists and anarchists, people that were just like ‘screw the rules, the right thing to do is to give people clean syringes,’” she says.

“I love being described as a rebel, I’ll take it any day, but I think sometimes the way it was presented, it took away from the fact that you can decide that the rules are killing people, and that you will not follow these rules,” she continues. “Historically that’s always been how people make things evolve.”

A previous version of this story incorrectly stated where Gagnon first studied nursing.