When mental illness is not just in your head

How gut bacteria could be affecting your moodBy Ebonie Walker and Haneen Al-Hassoun

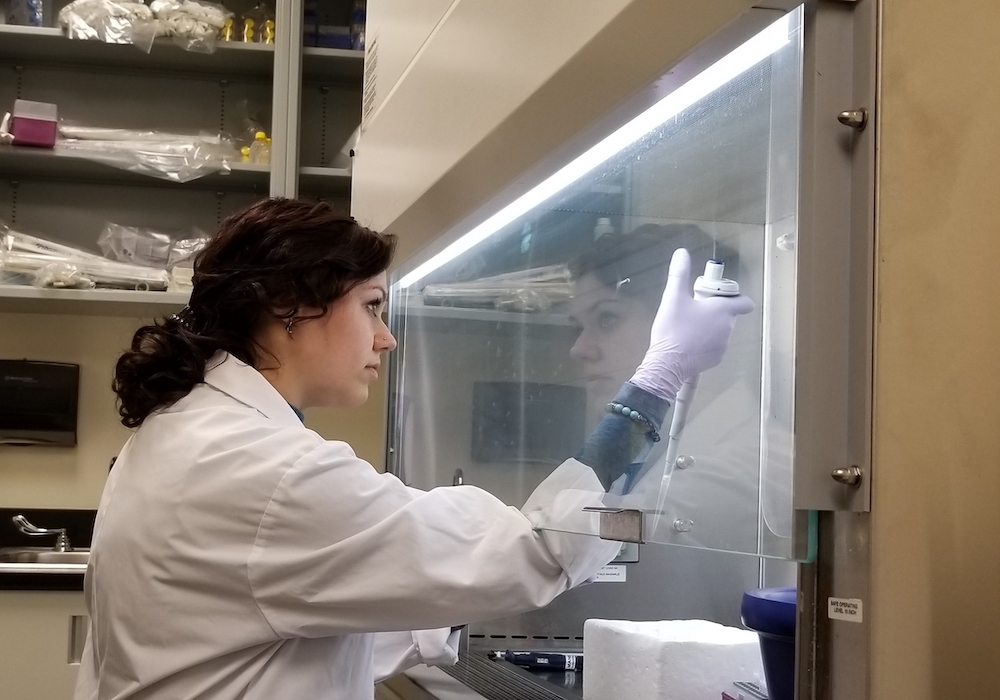

During her undergrad, Ana Santos was diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder and major depression. And like many people diagnosed with these mental health disorders, she was put on traditional medication to manage her symptoms. However, this did not work for her.

Santos has always been interested in the effect of food on people. She pursued a minor in food science. This and a neuroscience course led her into the world of diet, microbiomes and mental health.

She decided to make herself her own guinea pig and experimented with all kinds of food, until she found a diet that reduced the symptoms of her mental health disorders—enough to ditch the prescribed medication.

“Seeing how effective it was for myself, going from panic attacks multiple times a week to fast tracking into my PhD, was enough for me to believe so wholeheartedly that more of this research needs to be done,” Santos said.

Now, as a doctoral candidate at Carleton University, she’s doing just that by studying the effect of anxiety and depression on the gut microbiome and how diet can help with the symptoms.

Ana Santos was diagnosed with depression and anxiety in her undergrad. [Photo © Haneen Al-Hassoun]

The microbiome is the mini-ecosystem of microorganisms that live in and on the human body. The trillions of bacteria in our gut help us digest the food we eat by helping to extract the nutrients. Our microbiome also teaches our immune system the difference between symbiotic and pathogenic bacteria, allowing our immune system to respond accordingly.

Henry Schreiber IV, a postdoctoral researcher at the California Institute of Technology, likens the gut microbiome to an organ, albeit one composed of many different life forms. “It’s an organ the same [as] your liver or your kidney is,” Schreiber said. In other words, when all goes well, the microbiome can keep a person healthy, but when something goes wrong, the microbiome can make you sick.

Now researchers are starting to discover that the gut microbiome can also manipulate your mind, by producing molecules that modify mood, and by acting on a nerve that connects the gut at the brain. These finding might help medical professionals treat mental health more holistically, by considering the microbiome when they want to help the mind.

Now, the idea is that whatever [treatment] you give, may only have to be active in the gut and then rely on this gut-brain communication pathway to send healthy signals to the brain and reduce anxiety and depression

Paul Forsythe

Professor, McMaster University

Studies on the gut microbiome have spiked over the past few years, but some researchers began studying the gut microbiome almost four decades ago.

In the late eighties two scientists, Linda R. Hegstrand and Roberta Jean Hine published a study that looked at the histamine levels in germ-free and conventionally raised mice. According to Susan L. Prescott at the University of Western Australia, their work was initially overlooked. Yet as Prescott points out in the Human Microbiome Journal, these two scientists were among the first to propose that gut microbes may influence brain-chemistry.

Today, scientists are starting to understand the full implications of their pioneering work.

The gut-brain axis, explained

Our gut microbiome changes quickly in our first couple years of life. According to the European Society for Neurogastroenterology & Motility (ESNM), the human gut microbiome begins to stabilize itself by the time we are around three years old but it is never fully static.

Microbiome membership can change based on diet, stress levels and other environmental factors. For the past couple years, researchers, have been piecing together the links between stress, the gut microbiome and mental health. The once outlandish idea that intestinal bacteria could influence mental health has started to gain traction.

Paul Forsythe, who studies the gut-brain axis at McMaster University said there are three major biological systems–the immune, the nervous and the endocrine system—that act as communication conduits.

“They all pretty much act together to send signals from the gut to the brain,” he said.

In animal models such as mice, Forsythe and his research team found that bacteria in the gut can alter the animals’ nervous and immune system, and ultimately how their brain functions as a result. For example, germ-free mice models that were given the gut bacteria of obese mice, became obese as well.

Meanwhile, other studies show a difference between the microbiome of people with depression and the microbiome of non-depressed people, Forsythe said.

These studies suggest that altering the gut microbiome of people with depression to make it similar to that of those who aren’t depressed could perhaps reduce their depression too, he said. The idea is to identify certain bacteria “that seemed to be very good at influencing the central nervous system of behavior,” Forsythe said.

In fact, one recent study from Jeroen Raes and his colleagues at the University of Leuven in Belgium shows that people with depression have less of two specific types of gut bacteria, Coprococcus and Dialister.

Some researchers are looking at more than just bacteria acting on the nervous and immune system. Santos for example, is looking at less direct ways our gut microbiome could impact our mind. For example, how inflammation in the gut caused by stress might be modifying the neurochemistry of the brain.

She said the vagus nerve which runs through the brain and into the gut, creates a neural highway for signals between the two organs. This highway is constantly active—it’s what researchers call the gut-brain axis. If there’s a change in the rhythm or signals caused by inflammation, the information is transmitted to the brain, Santos explained.

“My last animal project shows that five weeks after chronic social defeat stressors—so the mice had been chronically stressed for the period of 10 days— they still had increased levels of gut inflammation,” she said.

Santos said this inflammation causes increased signalling up through the vagus nerve which increases inflammation in the brain—a symptom seen in people with anxiety with depression.

She said this signalling can happen because bacteria in the gut are causing inflammation there, or through what’s called a leaky gut.

A leaky gut is when, the gut barrier which is composed of a single layer of cells, becomes more permeable due to stress. Santos said this allows fragments of microbes or whole microbes to pass through the barrier and into the blood affecting how the brain fires and responds to stressful situations.

Ana Santos spends her days in the lab researching the gut-brain axis, in hopes of bringing clarity to this complex issue. [Photo courtesy of Ana Santos]

The future

Scientists agree that there is still much work to be done before research on the microbiome’s role in mood could lead to mental health treatments but small changes could start relatively soon.

Up until now, the dominant thought was that in order to properly treat mental illnesses, the treatment has to get into the brain, Forsythe said.

“Now, the idea is that whatever [treatment] you give, may only have to be active in the gut and then rely on this gut-brain communication pathway to send healthy signals to the brain and reduce anxiety and depression.”

One way to do this could be through the use of certain kinds of probiotics, called “psychobiotics” as a form of treatment against mental illnesses that may help to strengthen our microbiomes, he suggested.

These theories are already being tested in humans, Forsythe said. But he also urged caution: “I think we need to understand more about how probiotics are actually working,” Forsythe said. “It’s not entirely clear how the probiotics have their effect.” Or if certain probiotics have an effect.

There are many different ways in which probiotics might potentially affect the gut. For example, if the probiotics were to have an anti-inflammatory effect, then people with depression who also have high levels of gut inflammation might see better results than those who don’t.

Forsythe said there still needs to be large, controlled trials in humans to study probiotics and how they might help people with depression.

He added that this research offers a whole new way of thinking about mental health, which has traditionally only focused on the brain.

“It gets away from that thinking that it’s all in your head,” he said, “which is a cool paradigm shift in the way we think about mental health.”