Doc on demand: Healthcare goes digital

Even with robotic doctors and telemedicine apps in place, is Canada keeping up with virtual care?

By Marissa Kocent

The device, which will be released next year, wraps around a person’s neck and shoulders, and makes direct contact with the skin. A sensor that sits in the wearer’s ear like a headphone connects with a wire to the device. It is meant to be worn almost anywhere, whether the owner is relaxing at home or out playing sports.

“Vitaliti is designed to continuously monitor your vital signs at a very accurate clinical hospital grade level,” said Robert Kaul, the CEO and founder of Cloud DX, a Canadian start-up that aims to warp the country towards a new frontier of digital healthcare.

The idea is to treat patients based “on their symptoms, not on their schedule,” Kaul said. For example, Vitaliti records the electrical activity of a patient’s heart, and flags any vital sign abnormalities. It will be a complementary device to another Cloud DX product already on the market: a telemedicine kit that virtually connects patients with a doctor on-demand, catering to a growing demand for consultations from home.

Kaul hopes Vitaliti and the telemedicine kit will be widely adopted by people with chronic health conditions and those recovering from surgery because they “don’t have to schlep all the way to the doctor if they don’t need to.”

“Even if you’re perfectly healthy, you might monitor your blood glucose just to see how your body metabolizes food,” Kaul explained, highlighting the benefit of having a doctor available at your leisure to discuss results. “If you have spikes in your glucose at certain times of day or two glucose crashes at other times, maybe you can adjust your diet so you don’t need six cups of coffee to wake up in the morning.”

As more and more of the world goes online, healthcare is no exception. Fueled by the widespread adoption of smartphones and powerful internet connections, telemedicine and virtual care innovations—such as Cloud DX’s products—are helping to reinvent how healthcare is delivered to patients.

In Canada, where doctor shortages, overcrowded hospitals and long wait times impede access to healthcare, federal and provincial agencies are turning to technology for solutions. But even as virtual care technologies become increasingly available in Canada, some health professionals worry that the country is still playing digital catch-up.

Digital demands

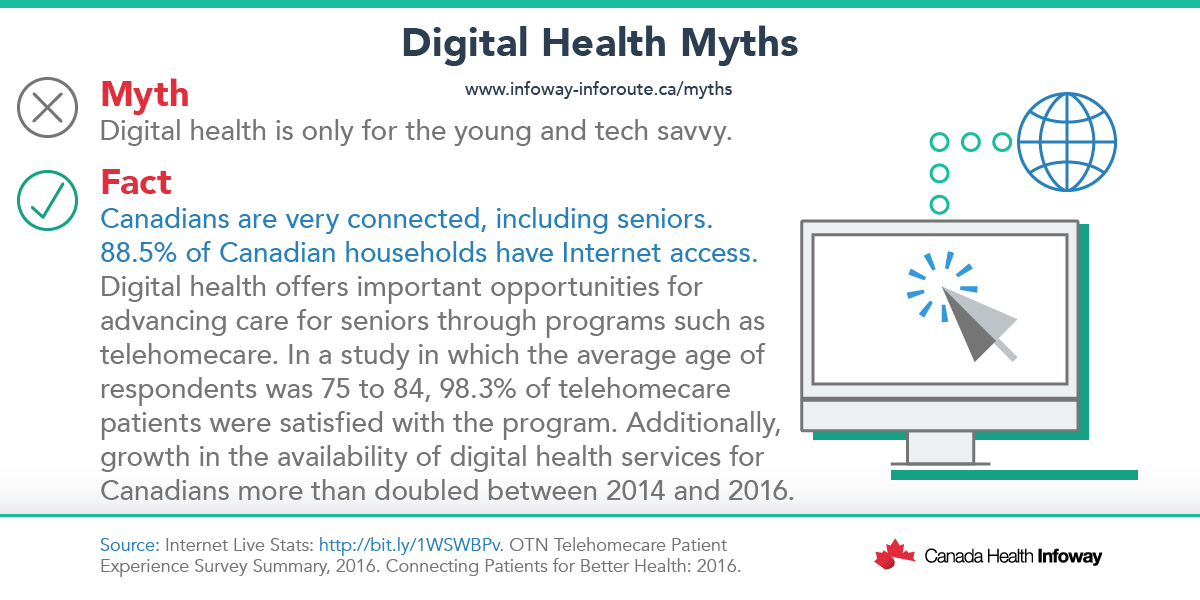

There’s all these terms for things telehealth: telemedicine, telehomecare, virtual care,” said Karen Schmidt, the communications director of Canada Health Infoway, an organization accelerating the adoption of digital health solutions across the country.

“Basically, it’s seeing somebody from a distance and having your concerns looked after,” she said, though there are slight distinctions.

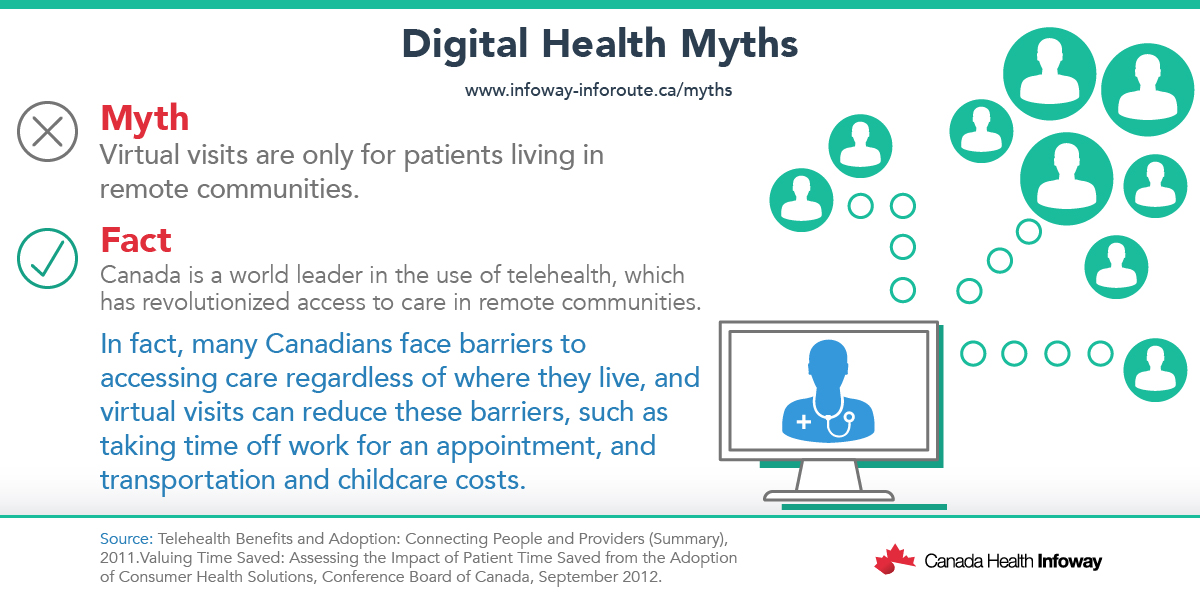

“It’s very beneficial for people who don’t have time to fit in waiting rooms and travel… [and] anything else that’s associated with taking time off work,” Schmidt explained.

Consider the eCare program, implemented by the Ontario Telemedicine Network, a not-for-profit funded by the province. It allows Ontarians with chronic lung and heart conditions—the majority of which are seniors–to be monitored and coached from home, cutting down on trivial trips to the doctor.

In Saskatchewan, a robot named Rosie treats patients in a remote First Nations community. A physician from elsewhere in Canada controls Rosie using a smartphone and can use video to connect with patients. Rosie can use a stethoscope, conduct ultrasounds and take electrocardiograms.

For Canadians who would do anything to avoid sitting in a waiting room full of sick people, there are downloadable apps that let you text, call or videocall a doctor instantly.

One of these apps is Maple, which according to its website, boasts it can connect patients with a doctor in two minutes or less. Nova Scotia resident Julia Melly downloaded Maple after seeing it advertised on Facebook and had a doctor diagnose her with a bacterial sinus infection over text.

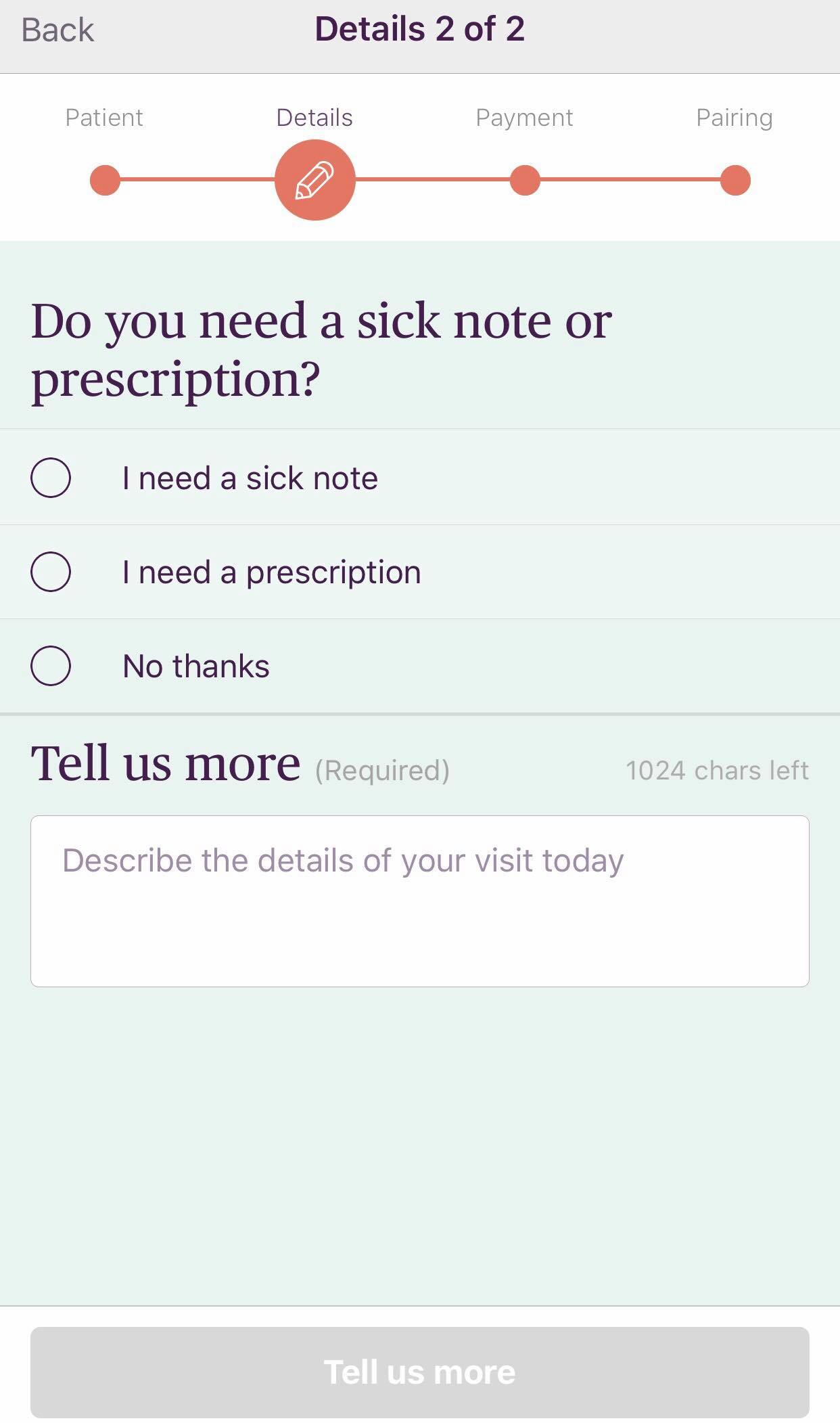

For Melly, there were both pros and cons to using the app. Maple requires users to pay per visit and it’s not covered by health insurance. But there are some advantages to the online encounter: “You can see the whole text transcript,” in case you forget some aspect of the medical advice, said Melly, who does not have a family doctor, like approximately 4.8 million other Canadians, according to Statistics Canada. Maple doctors fill out prescriptions and hand out doctors’ notes, just like at a regular clinic.

“My prescriptions were sent right away to my pharmacy,” added Melly, relieved.

“I never really thought that I would talk to a doctor online.”

What is telemedicine? Here are some common terms.

It can refer to everything from clinical services to two doctors discussing a patient’s results over video.

Telehomecare: Delivery of clinical services to a patient’s home using in-home monitoring devices.

Telemedicine: Delivery of clinical services, such as diagnosis and monitoring, over

Remote: When the patient and doctor are interacting, but are not in the same room.

Virtual care: Encompasses all the virtual interactions a doctor can have with their patients; email,

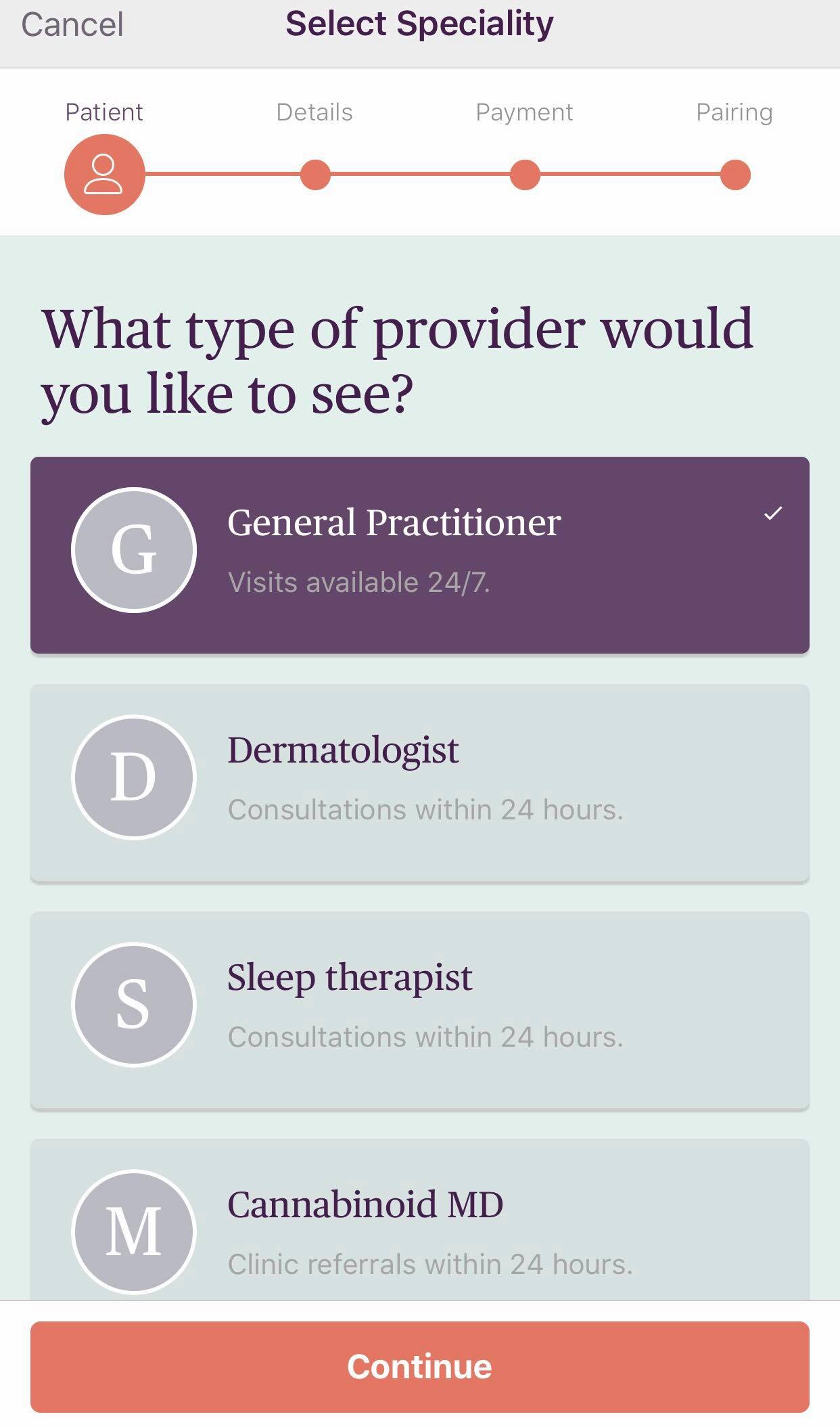

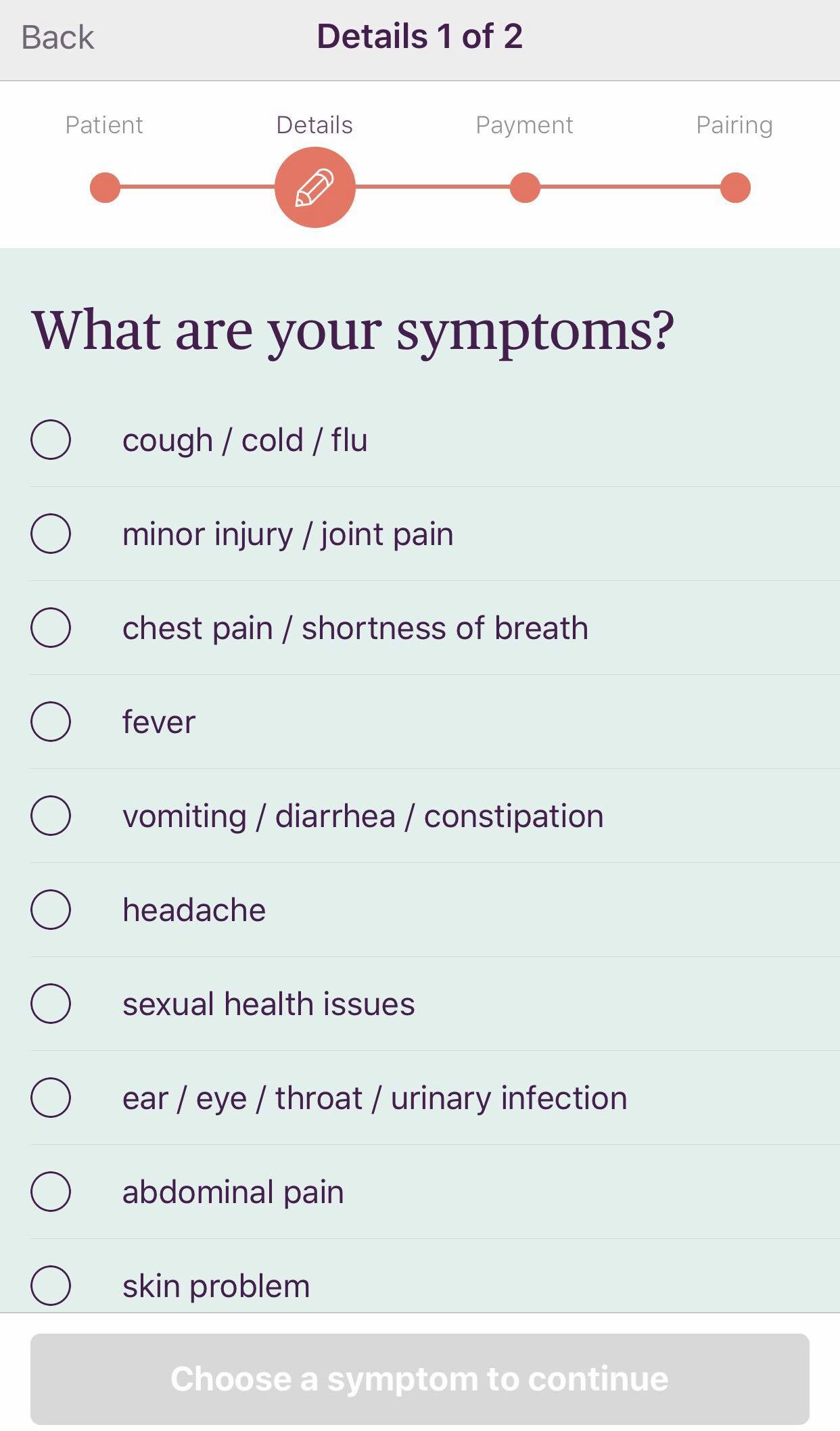

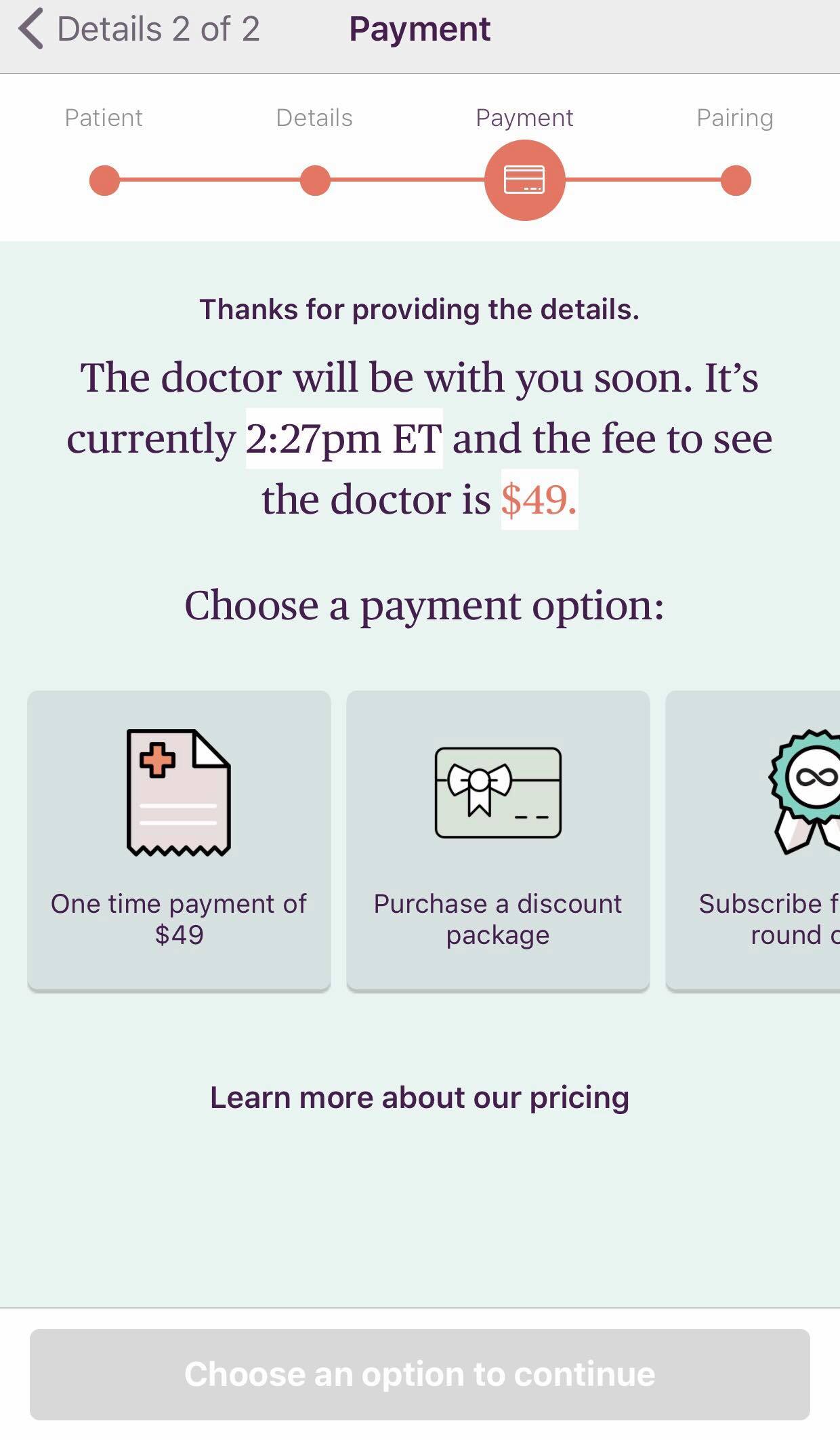

Maple is a Toronto-based telemedicine app. Flip

through to see what it’s like to request a doctor’s

appointment.

A burdened system

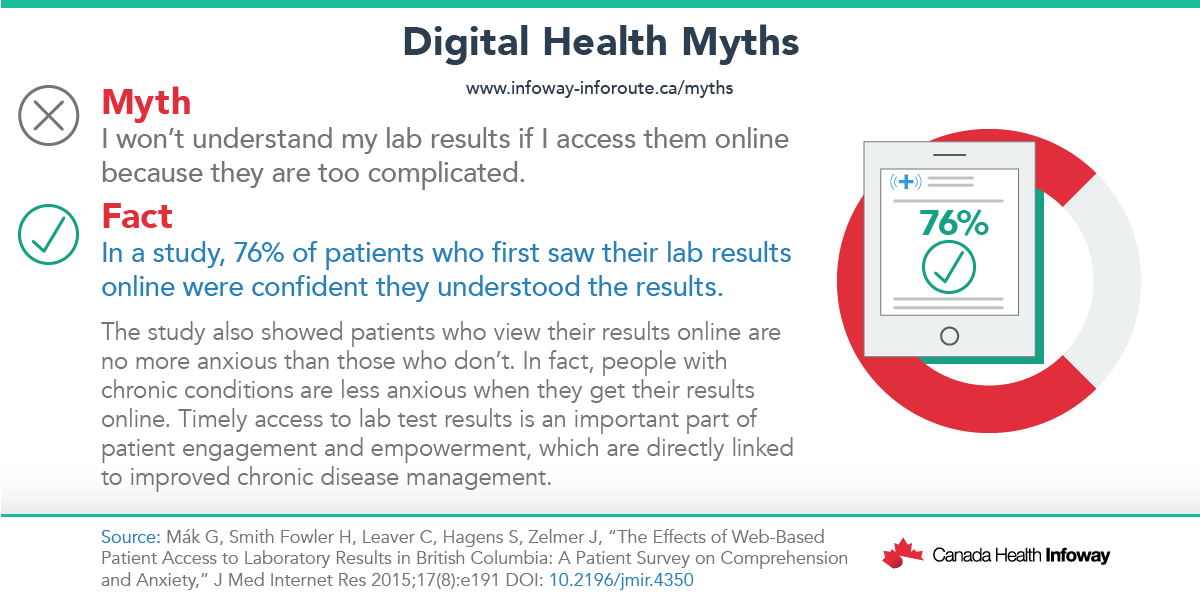

Melly is not the only Canadian who is unused to interacting with doctors online. According to a 2017 Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy survey, Canada’s digital health services scored poorly. When compared to ten other high-income countries, including the United States and Switzerland, Canada came last because many doctors aren’t available over email, lab results aren’t accessible online, and patients face long wait times, whether it’s to see a family doctor or specialist, or in emergency rooms.

Paramedic Carla Harrison observes some of these inefficiencies on the job.

“I see it every day, people call 9-1-1 for a lot of things and it’s not a medical emergency,” said Harrison, who works for the Toronto Paramedic Service, the largest paramedic service in Canada. Harrison says given the long wait times to access doctors, some patients view paramedics as a shortcut to care.

Paramedics in Ontario are obligated to outline all risks to a patient and encourage them to be assessed by a physician in the ER, even if their clinical presentation isn’t currently life-threatening. Though Harrison hasn’t used telemedicine on the job, she sees its potential in pre-hospital care because doctors would be making the call if patients should be brought to the hospital, potentially reducing the number of people at an already overcrowded facility.

‘Bullshit’ excuses

Yet online health care isn’t a cure-all.

Telemedicine recently faced criticism when a doctor at a hospital in California gave a patient a terminal diagnosis through a screen on a robot.

Bedside manner pitfalls notwithstanding, virtual care faces other challenges, including fraud and abuse, excessive treatment, inappropriate care – all concerns noted in a 2018 C.D. Howe Institute report on modernizing Canada’s healthcare system through virtualization.

“Of course, there are privacy concerns,” said Will Falk, one of the report’s authors. “But using the privacy concerns as an excuse to not modernize our health care system is simply unacceptable in 2019.”

“Are there a whole bunch of things that I’m not interested in talking to a doctor over on the phone or by e-mail? Absolutely,” said Falk, who teaches about healthcare innovation and policy at the University of Toronto. “But, to say that this is a reason not to use virtual care, I just think that’s bullshit.”

Falk scoffed at using what he called “vague generalizations people are making,” including a lack of compassion from the doctor when there’s no face-to-face contact, as the rationale for not implementing virtual care.

“You cannot tell me that on an icy February day, it’s in my mom’s best interest to go and be socialized at her doctor’s office in a room full of people with the flu,” he said. “Or the reason I can’t get my orange puffer renewed by e-mail.”

That being said, finding an appropriate business model is an obstacle to widespread integration, Falk explained, since “we shouldn’t be paying the same thing for text messaging as for full-on doctor’s visits” and many current services come with a price tag not all can afford.

“We need politicians to stand up and say in a direct way that patients have the right to a modern experience and to their data in electronic form,” he stressed.

A way forward

Canada’s free healthcare for “medically necessary hospital and physician services” is mandated by the Canada Health Act, said Maryse Durette, a Health Canada media relations advisor. Yet it is up to each province and territory to regulate primary healthcare in their jurisdiction, she said. This includes determining what tools, including telemedicine, should be used to deliver that care.

Since Health Canada reviews and approves new medical devices, including virtual care technologies, it established a new Digital Health Review Division last spring to streamline the evaluation of “innovative digital health technologies that have rapid development cycles,” in order to improve provinces and territories’ access to them, Durette said.

In late 2018, Canada Health Infoway, a federally-funded not-for-profit, also introduced Access2022, a country-wide initiative “not just focused on telehealth,” but rather “a movement to get Canadians better access to healthcare” by 2022, according to communications director Schmidt.

Part of the initiative includes pushing for increased accessibility to telemedicine. Under Access2022, Kids Help Phone, a provider of free telephone counselling to young Canadians, has created a new texting platform for children in crisis to use.

“Canadians deserve the best healthcare and we want to help them get it. Before we can get the best health care, you have to have access to it. Digital is the way to go,” said Schmidt.