ICU patients experience long-term cognitive effects

Researchers try to understand the possible role of sedatives, sleep disruption, and other medical interventions on the long-term cognitive abilities of ICU patients

By Polina Gankina and Natali Trivuncic

Diazepam, commonly known as Valium, is a type of benzodiazepine. [Photo © Dominic Milton Trott]

Locked in an old, abandoned bathroom, Yasmin Awada remembers feeling nervous while she fiddled with the door handle. The sink slowly leaking, as an individual drop dripped into the small puddle of the sink’s basin, the next drop forming seconds afterwards. Mysterious creaks and beeps flooded the room.

Suddenly, the room filled with a bright light, as she began to open her eyes.

“It was just a dream, but the noises were real, what I had been hearing were the noises of the ICU,” she said.

Awada found herself in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) in January after she was diagnosed with bronchitis, causing stress in her lungs.

Due to the ICU’s fast-paced and noisy environment, combined with her intense body pain, she was given sedatives to help her rest during the course of her three day stay.

Bright lights, beeping machines, nurses coming in and out of the room, and overhead announcements are common factors which affect patients in the ICU. Patients, like Awada are often given sedatives to help ease them to sleep.

Although Awada did not suffer any long-term problems after her stay in the ICU, not everyone is as fortunate. According to a 2013 study published in The New England Journal of Medicine, “patients in medical and surgical ICUs are at high risk for long-term cognitive impairment.”

The study of 821 ICU patients, led by Pratik Pandharipande at Vanderbilt University, found that 40 per cent of patients had global cognition scores similar to those with traumatic brain injury three months after leaving the ICU. One year later, 34 per cent of patients exhibited signs of moderate traumatic brain injury, while 24 per cent had cognitive scores similar to patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease.

“We as health care providers need to be aware of this when patients come to us with memory problems…, and not blow it off as saying, ‘This is all going to get better,’ because we really don’t know,” Pandharipande told USA Today.

In the study, Pandharipande and colleagues found patients who had experienced long durations of delirium during their hospital stay, were at higher risk for cognitive impairments. Since the study’s publishing in 2013, many more researchers have investigated the possible role of sedatives, sleep disruption, and other ICU medical Interventions on the long-term cognitive abilities of ICU patients.

According to the Canadian Institute for Health Information, 11 per cent of the population, approximately two million Canadians, stayed in the ICU in 2015.

Keeping organs functioning has long been the primary concern in the ICU, said Laurent Brochard, director of the interdepartmental Division of Critical Care Medicine at the University of Toronto. Now increasingly, researchers who focus on ICU care are turning to the mind, looking to understand how time in the ICU affects a patient’s long-term cognitive function.

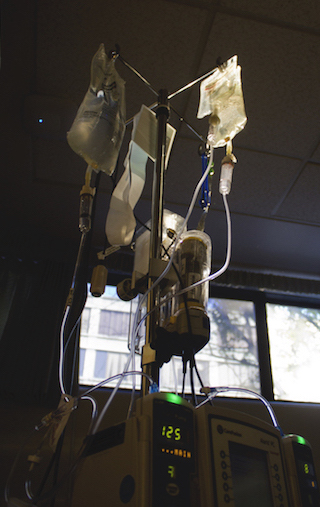

IV device found in the ICU. [Photo © Quinn Dombrowski]

Irene Telias, a Critical Care Fellow at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, studies the effects of sleep and sedation in the ICU. She said the most common sedative used for sleep is benzodiazepine, used as an IV drug.

According to Healthline, sedatives work to modify certain nerve communications in the central nervous system by increasing the calming effects of the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA). By increasing the effects of GABA, benzodiazepines are often used to calm or sedate patients.

In 2015, the Canadian Drug Summary reported 10.5 per cent of the population were prescribed sedatives.

[Visualization by Polina Gankina]

One concern about the use of benzodiazepines is the potential for addiction. According to Drug and Alcohol Services South Australia, 30 to 40 per cent of people who take prescribed quantities of benzodiazepines for longer than one month, feel withdrawal symptoms after stopping their usage.

Sleep disturbances are one of the withdrawal symptoms, among others like nausea, anxiety, and irritability.

Beyond the problematic side-effects of benzodiazepines, some researchers have found that prolonged benzodiazepine usage in ICU patients may also cause delirium- the main criteria for the cognitive decline found in Pandharipande’s study

In an audio interview published by the University of Utah, Richard Barton, professor of surgery and director of the Surgical Critical Care Unit at the University of Utah Hospital, explained that delirium is a change in the brain which causes confusion and emotional disruption.

“[Patients] seem normal and suddenly they would say something that is completely not cohering with what you’re talking about,” Telias said. Simple cognitive tests such as pointing to an object and saying its name can be difficult for delirium patients to understand, she added.

According to a report by Canadian Critical Care Trials Group (CCCTG), 70 per cent of the 63 patients monitored over six months experienced delusional memories 28 days after discharge from the ICU. The CCCTG report found that delusional memories were not related to sedatives- but another study found the opposite, highlighting the lack of consensus in this research area.

An article published in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Management (AJRCCM), found critical care patients were likely to experience delusional memories that were related to sedation. The researchers, led by John. P Kress, director of Medical Intensive Care Unit at the University of Chicago, found that delusional memories can also induce further issues for patients post sedation, such as PTSD from their time in the ICU.

Although sedatives may play a role in the long-term cognitive effects in the ICU, not all patients in the ICU require sedatives. Patients that require sedative drugs are typically those connected to breathing machines, making it hard to parse whether long-term cognitive problems are related to sedatives or to the effects of being connected to a breathing machine.

“Its difficult to separate the effects of the drugs to the effects of the other various things that are happening to a very sick patient in terms of neurocognitive function,” Telias said.

For this reason, it is difficult to pick apart the short, and long-term effects which sedatives may have on patients.

“It really depends on the baseline degree of injury that [patients] already have to their brains, either because they have some underlying brain disease or they have a stroke or a seizure or any infection to the brain,” she said.

Until the root causes of the ICU-related cognitive decline are determined, some medical professionals are being cautious about sedative use. Frances Chung, professor of the Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine at the University of Toronto, said she has noticed recently that medical professionals are avoiding sedative use, where possible.

Sedative use is typically only common in the ICU, and is hardly seen in the surgical ward, Chung said. One reason is that it is uncertain whether sedated sleep is restorative for ICU patients, Brochard said.

Similarly to Telias, Chung said it is difficult to say the exact long-term effects of sedative use on ICU patients. “One thing is for certain, sedatives make almost every patient incredibly drowsy,” Chung said.

Patients under sedative drugs usually have different brain activity that does not follow normal sleep patterns, something that can be observed by examining brain wave patterns on an EEG Machine, Telias said. The patient appears to be sleeping but functionally their brain is not actually sleeping; it’s just disconnected from the environment as the body stops responding to stimuli like noise and touch.

Critical Care Canada reports sleep quality in ICU patients is reduced, as patients often experience 20 to 80 awakenings per hour of sleep.

The correlation between sleep, sedation, and recovery is still relatively new but there is evidence that a lack of sleep has many downstream effects in the body, including a lack of cognitive function.

As researchers continue to study the long-term effects of being in the ICU, the hope is that medical professionals will be able to send these patients home in the future without concerns about cognitive decline.

[Visualization by Natali Trivuncic]