[Photo courtesy of The People Speak! via flickr (CC BY 2.0)]

System in crisis

Assessing youth mental health care in OntarioBy Mamta Manhas and Emily Fearon

Content Warning

This article has a story about suicide and discusses self harm.

When Jenepher Watt called the London Free Press in 2015 after she was forced to sleep on an emgergency room floor, her distress signalled a system that was faltering badly. Watt, 18 at the time, was waiting in London’s Victoria Hospital to be given aid for the mental health challenges she was facing. She was hailed a whistleblower for revealing a struggling system, and the exposed mistreatment of patients led to the hospital re-examining its procedures, but Watt’s own battle continued. One year later, she was rushed to the same hospital three times in 11 days after suicide attempts, only to be seen and discharged each time. On June 8, 2015, Watt took her own life.

Despite the attention to Watt’s story and the changes that ensued in the London hospital, there are signs Ontario’s health care system still needs much more work.

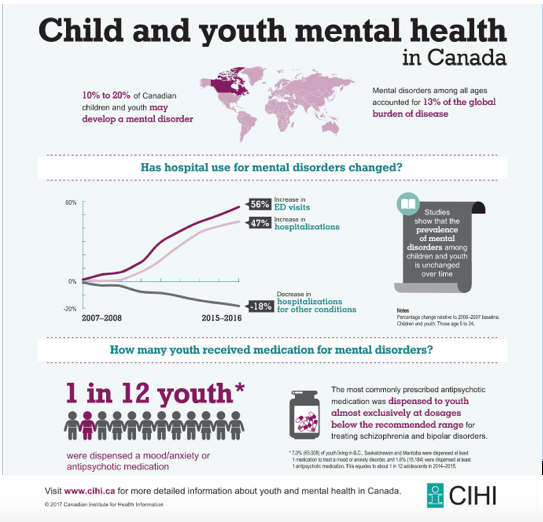

There is reason to believe demands on the stressed medical system will increase in coming years, especially the need to provide youth with mental health support. Canadian data shows a rise in numbers of youth hospitalized for self harm, and wait times for hospitals and community support services remain notoriously long.

“I think things have been bad enough that most people within and outside the system would say that there has been an ongoing crisis,” said Jonathan Sher, a journalist for the London Free Press who has covered healthcare since 2011, including Watt’s story. “It has, if anything, gotten worse over time, and that while there has been some incremental changes that tended to improve the level of service, that at best those incremental changes have not closed the gap.”

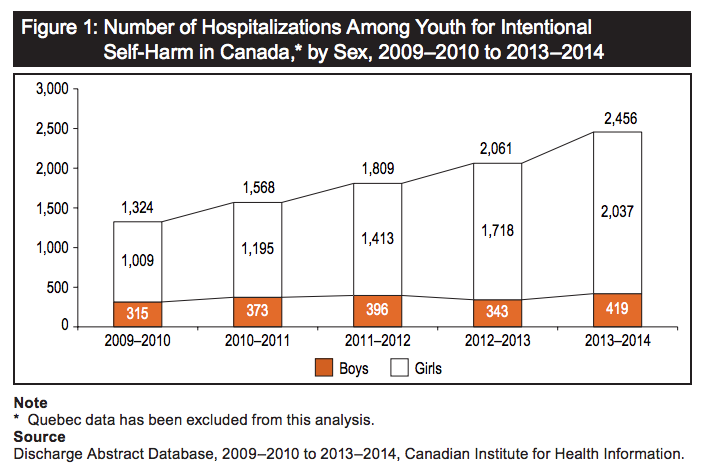

In 2014, the last year data is available, almost 2,500 Canadian youth aged 10 to 17 were hospitalized for self harm, reports the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). Girls made up 80 per cent of these hospitalizations. CIHI also recorded that between 2009 and 2014 the number of girls hospitalized increased by 110 per cent, and 35 per cent for boys. There was a 90 per cent increase in the number of girls hospitalized for cutting themselves, but the most prominent cause of hospitalization for boys and girls was poisoning.

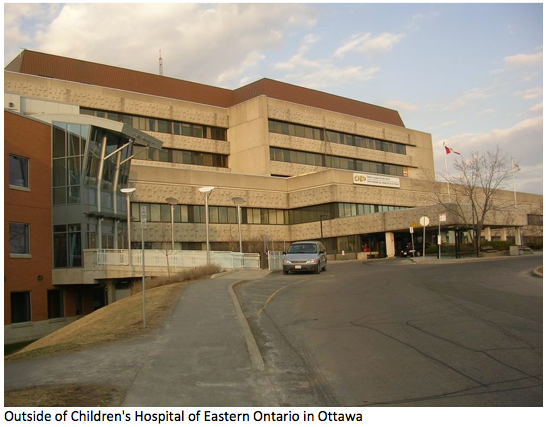

Dr. Sinthuja Suntharalingam is a child and adolescent psychiatrist at the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario (CHEO). She said CIHI’s data accurately reflects what she has seen in her work with acute cases of mental health distress: there is an increasing demand for support and more cases of youth needing care. “It’s not just at CHEO, I think it was all across Canada.”

Suntharalingam said the hospital’s approach to youth mental health has changed from longer-term treatment to acute crisis response in order to accommodate the increase of people seeking help.

“You will hear this as a general concern is that we need to have more things in place to meet the mental health needs of our children, and we do advocate for it, we ask for it, we do the best we can,” she said. “We are trying the best with what we’ve got, we just need more personnel, better mental health training as well as the resources to support that.”

Even more Ontario youth are taken to the emergency room for self-harm; in 2013 and 2014, the numbers reached 3,411 youth. Other data from CIHI indicated in 2015/2016 emergency room visits for youth with mental health disorders increased 56 per cent.

The increase in numbers could also be attributed to more youth seeking help according to Mary Bartram, a doctorate candidate at Carleton University and the former director of the Mental Health Strategy for Canada, which developed the first mental health strategy for the country nation-wide. “We’re getting more youth being willing to take care of themselves, we don’t see it only in hospital but…we also see it in community services, kids help lines are getting more calls, there’s more referrals to community level mental health centres for youth.”

Bartram notes that CIHI’s data might describe the cause of hospitalization as self-harm but could really be showing the numbers for suicide attempts among young people. As Suntharalingam explains, “self-harm when in psychiatric terms, it’s more to do with behaviours like self-mutilation by cutting, burning and things like that. Then we have…a suicide attempt, which would be intentional overdose.”

Currently, Ontario’s mental health policy takes a collaborative approach, relying on both community and medical services to help youth in crisis. A mental health and addictions policy was adopted province-wide in 2011 that aimed to address the needs of all Ontarians regardless of age. One of the main goals was to identify mental health and addiction problems early on, recognizing that mental illness typically begins developing during childhood or in one’s teenage years.

There has also been more support for mental health workers and resources provided for suicide prevention initiatives, Bartram said. “There’s good evidence that approach is working,” she said of the policy which encompasses community support and medical services, but she also recognized there’s a lot of catch up still to do.

“There’s been a longstanding gap and [lack of] access to mental health services for 50 years and it’s not going away overnight,” she explained. “I think they’re moving in a good direction, they could increase their funding by a lot more, but they do seem at least to be prioritizing youth mental health.”

Although there’s no concrete reasons why females have a higher rate of hospitalization than males, Suntharalingam thinks it may have to do with how males and females deal with stress and anxiety.

“Men or the boys tend to…outwardly express their frustrations and emotion, and that manifests in more behavioural disorders. Girls on the other hand, I find they’re more internalizers. So, they keep all their emotions inside, they don’t have a good way to express their pain, and therefore I think, in my opinion, they tend to self-mutilate and overdose.”

Bartram said females have higher rates of mood and anxiety disorders but also higher rates of seeking care. But whatever the motivation or reason for getting help, the steady climb in the number of girls and boys needing mental health services and care has impacts.

“Patients end up feeling worse-off after being in the

emergency department for many days,

than they were when they first got in.”

One significant impact is wait times to see medical professionals, as seen with Watt’s story when she was forced to sleep on the hospital’s floor. “What we hear is that patients end up feeling worse-off after being in the emergency department for many days, than they were when they first got in,” Sher said.

The wait times are a big problem for youth with mental health issues, Suntharalingam says. “It’s really really bad at this time. There’s simply a shortage of child psychiatrists and things like that.” She said she would like to see more funding for mental health training and community services: “There is a big shortage of things to meet the mental health needs.”

Wait times have been known to extend as long as five months for services in Ottawa, but a report released in late January shows wait times for youth mental health services have decreased at CHEO and the Royal Ottawa Mental Health Centre. The effective action plan to reduce wait times has been in motion since 2016 and includes initiatives like the two hospitals allowing families to select the physicians they want to meet with.

In mid-March, Premier Kathleen Wynne announced a $2.1 billion investment into mental health initiatives. The money would go towards an additional mental health worker per high school, 15 more youth wellness hubs, creating safe and affordable housing and further financial investment over four years.

However, this is contingent on the provincial Liberal’s re-election this summer. In the end, the system has to play catch up and it may take many years to come. “We can’t just increase the capacity of the system ten fold over night,” said Bartman. “That would be a tall order.”

“People who are suffering from mental health issues or their family or friends, generally they would tell you that the system has been in full-blown crisis for many many years” Sher said. “If you talk to people who work within the system, most of whom are at hospitals or agencies that are funded by the provincial government, there’s sometimes more of a reluctance to be unduly critical of the status quo because they’re having to balance advocating for their patients with not being too damning about the government that funds their services.”

Resources

Ottawa Crisis Line: 613-722-6914

Outside Ottawa: 1-866-996-0991

Kids Help Phone: 1-800-668-6868

But there is urgency to the matter. Jenepher Watt’s story continues to haunt a system that too often fails young people who struggle with mental health. Some are hospitalized for self harm and while still more pass through emergency departments. What is not clear is how many others are struggling in secret. Here the lack of data is a silent reminder the the full extent of the crisis remains unmeasured.