‘Don’t Worry, Be Happy:’ Social prescribing takes off in Ontario

Why more healthcare workers are prescribing community activities to treat mental illnessBy Katherine Lissitsa and Adam van der Zwan

Jean-Marie Messier, 65, felt a sense of sadness creeping in when he found himself isolated after retirement a decade ago. “It was the first time in my life that I found my schedule to be completely empty, but I didn’t have any hobbies or pastimes,” he said.

Refusing to waste his time, Messier made volunteering his hobby. He worked closely with his local health centre in the town of Kirkland Lake Ont., holding down administrative positions, until the Timiskaming District health centre offered him the role of a “health champion” — a volunteer who oversees various community activities related to a new project called social prescribing.

The practice involves health-care workers referring patients to community-based activities instead of prescribing clinical treatments for loneliness, depression, and other mental and physical health issues. While activities like knitting a scarf, playing board games, heading to the museum or catching a movie are often pastimes for a quiet weekend afternoon, they’ve now entered the Canadian healthcare system as officially prescribed treatments. The end goal is to improve a person’s overall well-being, to reduce the need for clinical prescriptions and to cut down on medical appointments.

A Canadian pilot project

The Alliance for Healthier Communities, a coalition representing community health organizations in Ontario, launched a social prescribing pilot in September 2018. Eleven community health centres in Ontario have now embraced the project and are tracking its progress through data collection over 15 months, to assess if it would be a sustainable practice in the long-run.

One of the activities Messier runs is a photography workshop at the local adult education centre. He said that after a few classes, he could already see the positive change in people’s moods.

“I saw it as a good way to not only battle my own isolation, but to help others with loneliness as well,” said Messier.

Research says loneliness can have profound effects on the human body when experienced for long periods of time. A study published in 2010 by PLoS Medicine found that weak social connections can lead to a shortened lifespan similar to one caused by smoking 15 cigarettes a day, and greater than that caused by obesity.

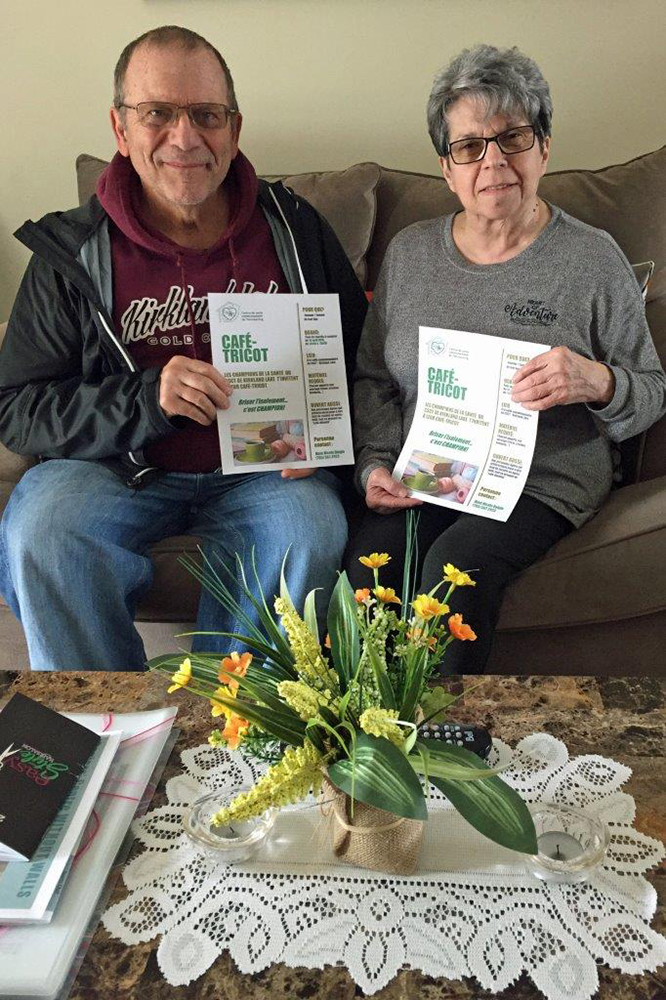

Jean-Marie Messier (left) and Nicole Daigle (right) both volunteer as health champions at the Timiskaming health centre. They recently helped launch a knitting cafe located in Kirkland Lake, for which they created a promotional poster.[Photo courtesy of Jean-Marie Messier]

When isolated, a human can experience a mental state of distress known as the “fight or flight” response. The person’s heart rate increases, muscles become tense, and breath quickens in order to prepare them to fight a threat, whether it’s an immediate danger, or a long-term stressor, like a lingering deadline. A constant state of stress increases a person’s risk of inflammation, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and early-onset dementia.

Around four years ago, U.K. doctors began prescribing social activities through the country’s National Health System (NHS) to treat mental and physical issues. Many British practitioners are now connecting their patients with link workers — people who can tailor health plans for patients and connect them to local support groups.

Britain busts loneliness the communal way

It’s a strategy that resonates with Dr. Clifford Stevenson. For the past 10 years, Stevenson, a social psychologist at Nottingham Trent University in the U.K., has studied how one’s feelings of community connectedness can impact their health.

“If you’re embedded within your local community and have good relations with other people, you’re probably going to cope better with what life throws at you, rather than if you’re isolated and alone,” he explained.

In January 2019, the NHS released its new long-term healthcare plan, which aims to hire over 1,000 trained link workers by 2021 and refer over 900,000 patients to social prescribing services by 2024.

“[Doctors] are well aware that patients are coming to them with social needs rather than healthcare needs,” said Stevenson. By referring patients to outside programs, doctors will be able to free up time for themselves to focus on the patients that need more serious medical attention, he added.

Inspired by the work done in the U.K., the Alliance for Healthier Communities decided to launch their social prescribing project across the Atlantic, with the help of British researchers.

Staff and clients of the Centretown Community Health Centre gathered to celebrate International Social Prescribing Day on Mar. 14, 2019. The centre’s data analyst Alexandre Mayer (second from the left) said he’s never taken part in social prescribing activities, but he hoped this one will be the first of many he can attend. [Photo © Katherine Lissitsa]

Janis Dahl, the health promoter running the project at the Centretown Community Health Centre (CCHC), in Ottawa, said that referring clients to the community has been a long-time practice, but the project gave it a name and a larger purpose.

A doctor’s bread and butter are to look at specific symptoms and come to a diagnosis. The healthcare workers in community centres, however, prefer a holistic approach.

“It’s not just looking at symptoms and medical concerns that the clients are presenting with, but taking a step back and looking at the whole picture of what impacts people’s health,” said Dahl. A client’s personality, interests, lifestyle, finances, housing and more are also considered.

Fran Charlebois, a client at the CCHC, was at her afternoon fitness class at the centre on March 14 when she was given a brochure for a “Talent-Optional Musical Gathering” happening down the hall later that day.

Dahl said clients at the CCHC were excited about the social prescribing project because loneliness is especially prevalent now, with the increased use of social media and technology that keeps people indoors instead of out in the community. “It’s getting people thinking differently about the possibilities and the importance of belonging and breaking social isolation,” she said. [Photo © Katherine Lissitsa]

Out of the songs played at the musical gathering, Charlebois’ favourite was “Hallelujah,” by Leonard Cohen, she said, adding that she loves to sing and thinks the centre should hold events like this one more often. [Photo © Katherine Lissitsa]

After eight years in the Good Companions choir, at a local seniors’ centre, she thought she’d give the event a try. She met with a couple of other attendees in a brightly lit room, where staff members strummed their guitars and tapped their tambourines. “I think this is wonderful,” said Charlebois, after songs like “Don’t Worry, Be Happy” filled the room and were followed by laughter and ardent rounds of applause.

The centre is working to collect the number of client referrals to community-based activities like the musical gathering and is tracking the outcome of those experiences from the clients’ perspective. The CCHC is currently tracking around 40 clients. [Video © Katherine Lissitsa]

Getting more doctors on board

Dahl also said that some of the centre’s clients are often affected by poverty and inadequate housing, and don’t receive enough mental health support or live with “toxic stress.” And while she acknowledged that attending a musical gathering won’t fix the greater issues in these clients’ lives, cultivating a sense of belonging within a community can alleviate loneliness and isolation.

Dr. Stevenson said some doctors in the U.K. are still resisting. “They’re chained to the medical model, they’re not familiar with social factors, and they’re often not convinced it’s going to work.” One way to persuade them could be to record feedback from patients so doctors can learn about how they’re faring among their social circles, he said.

Establishing this feedback loop would also encourage doctors to properly convey the importance of social prescribing to patients who may be concerned or hesitant. “If you go to your doctor with chronic health problems, and your doctor recommends that you join a knitting group, you might actually be a bit offended,” said Stevenson. “Doctors need to understand fully what the benefits are, themselves.”

Marty Crapper, the executive director of the Country Roads community health centre, said this new practice would benefit rural Ontario communities especially. “We don’t have museums or even gyms that we can partner with to get support,” he said. “So much of the support comes from individuals in the community.”

It’s more appropriate to deal with health issues with the proper intervention, added Marci Bruyère, the health promoter at the Country Roads centre. “Doctors are medical in their scope and they’re not the most well-suited to deal with a lonely person in a rural community.”

Crapper thought social prescribing could easily be a viable practice within Ontario’s healthcare system. “You hope that this is the sort of thing the government would pay attention to because it’s a cheaper way of improving health,” he said.

Dahl hopes the practice expands outside of community health centres.

“I’d be curious to see if this could grow bigger, so more people can really see how important social inclusion and a sense of belonging is.”