Bringing back the dead: Scientists debate the pros and cons of de-extinction.

Humans are the single largest cause of animal extinction. As biotechnology advances, do we have a responsibility to restore extinct species?By: Anna Sophia Vollmerhausen

It’s a bright and clear day on the otherwise cold and remote tundra in Canada’s North. Herds of caribou huddle together, grazing on the sparse grass.

Suddenly, another mammal lumbers by, one with two long tusks and a furry coat that hasn’t roamed the Earth for nearly 10,000 years. Standing 10 feet tall and weighing almost 6,000 kilograms, the creature is a remnant from the last Ice Age—a woolly mammoth.

If some scientists have their way, this extraordinary scene could become realty in the not-so-distant future. Thanks to the science of gene-editing, prospects for de-extinction—the notion of bringing back extinct species—have never looked better.

But just because we have the power to bring back extinct species, should we?

According to Joseph Bennett, a biology and conservation professor at Carleton University, the answer should be a resounding “no.”

“If you’ve got the resources to make a choice,” Bennett said, “you’ll work on the living, not the dead.”

“If you’ve got the resources to make a choice, you’ll work on the living, not the dead.”

Sitting in his office at Carleton University, Joseph Bennett said that de-extinction is a costly process, and that money would be better spent on conservation efforts. [Photo © Anna Sophia Vollmerhausen]

Bennett is the lead author of a recent study published in Nature Ecology & Evolution that seeks to answer the question of whether or not it’s worth spending money on bring back extinct species.

As the study shows, it’s more expensive to bring back an extinct species and to have to care for it than it would be to work on the conservation of existing species.

Others disagree.

The California-based Long Now Foundation’s Revive & Restore project aims to “enhance biodiversity through the genetic rescue of endangered and extinct species,” according to its website. For a few years now, the group has been working to bring back extinct species such as the passenger pigeon or the heath hen.

Most notably, the Revive & Restore team has been working to bring back the woolly mammoth, which died out between 3,000 to 10,000 years ago.

Efforts to revive this ancient beast involve the creation of a hybrid embryo, by combining mammoth genes with Asian elephant DNA to create a “mammophant.”

Combining the genetic sequence of an extinct species with that of a closely related species—such as mammoths and elephants—is currently the most viable way of potentially reviving an extinct species, although the process is still in the early stages.

The challenges of de-extinction

Jordan Mallon is a research scientist in paleobiology at the Canadian Museum of Nature, and said he has a personal interest in de-extinction. According to Mallon, the technical challenges of reviving extinct species are likely to be overcome in the next few generations.

“The real challenge is the moral one—should we even be doing this?” Mallon said. “I think we have yet to reach a firm conclusion on that one. Sadly, I’m not convinced that the moral question is one that will stop anyone from bringing an extinct species back to life. It’s never stopped people from doing unwise things before.”

Scientists have yet to successfully bring back an extinct animal, since the process isn’t as easy as it may seem. First, they need a DNA sample from the species they’re trying to resurrect, as well as a closely related living surrogate that can carry the offspring to full term. Even in cases where all those criteria can be met, there’s no guarantee of success.

In 2000, the last Pyrenean ibex—a type of wild mountain goat—died. Nine years later, scientists managed to create a clone of an extinct species for the first time, although it later died after only seven minutes, due to birth defects.

This illustrates one of the common problems with de-extinction—the uncertainty of whether or not the species will survive.

“We weren’t actually able to estimate in our study because nobody knows what the uncertainty is,” Bennett said. “We know it’s high, but we can’t set a level on how uncertain it is to bring an extinct species back, and how uncertain is it that we could actually accomplish that.”

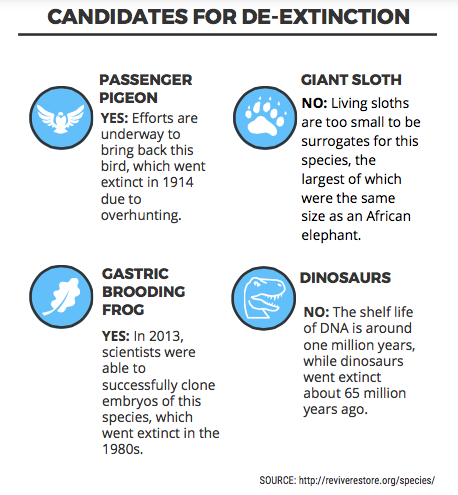

Some species are better candidates for de-extinction than others, depending on how long they’ve been extinct for, and whether or not a closely-related surrogate exists. [Infographic © Taylor Barrett]

The debate around de-extinction

If the technical hurdles can be surmounted, arguments both for and against de-extinction take on an ethical dimension. Since a driving factor in the extinction of many species has been human activity, the notion of “righting a past wrong” features highly on the pro-de-extinction side. But the counterargument focuses more on the well being and potential behaviour of these hybrid animals.

“If you could imagine a mammoth being raised by an Asian elephant surrogate mom, or some kind of a human trying to intervene somehow, how do we know that that thing would actually be happy in its environment, or actually function as a social creature?” he said.

In an interview with The Guardian earlier this year, George Church—the scientist leading the woolly mammoth team—said they are just two years away from creating a hybrid embryo. This embryo would then have to be carried by a surrogate mother, in this case, an Asian elephant.

But, Bennett said he sees a number of concerns surrounding the woolly mammoth project.

“If you’d imagine the difference between a mammoth and its surrogate mom . . . the difference between a mammoth and an elephant is like the difference between us and a gorilla—imagine us being raised by a gorilla,” he said. “Who is to say that that Asian elephant mom from the jungles of Asia would be able to teach an Arctic creature to actually function in its environment? It’s just not feasible.”

Environmental changes are also an issue when thinking about reintroducing these hybrids into the wild, he said.

“The Arctic that [the mammoth] went extinct in at the end of the last Ice Age is completely different from the Arctic now,” Bennett said. “For a lot of those creatures, their environments are forever gone, the environment went extinct with them.”

For his part, Bennett questions whether or not it’s ethical to spend millions of dollars to bring back a mammoth, when that money could be used to save dozens of other species from extinction.

“[If] you bring one species back from extinction, you increase the biodiversity by one,” he said. “But of course, by choosing to work on that one and not one of the 200 to 2,000 other species per year that are going extinct, you’ve essentially chosen to let other ones go extinct.”

Is conservation the better bet?

Mallon said he agrees that money is better spent on conversation, rather than de-extinction, and compared it to the colonization of other planets, such as Mars.

“It’d be far easier and more cost-effective to try and fix Earth’s problems than to try to move part of the population to another planet,” Mallon said.

However, Church said in an Ottawa Citizen article that releasing the creatures back into the Arctic would be beneficial to the environment, by “punching through” the layer of snow over the permafrost. This, he said, would allow cold air to come in and prevent it from melting.

But, Bennett disagrees.

“If you were going to be putting a lot of resources into something to prevent climate change, is the woolly mammoth the solution to climate change on our planet?” he said.

“No. It’s ridiculous.”

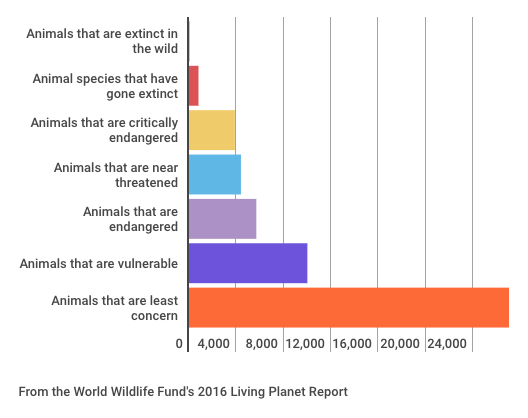

An estimated 200 to 2,000 species go extinct every year, according to the World Wildlife Fund. [Infographic © Taylor Barrett]