Canadian stroke victims at greater risk of dying in rural hospitals, new study finds

By Mike Barry and Naomi Librach

When a stroke happens, every second counts. In urban centres, victims can usually access optimal care in their area.

Now, add hundreds of kilometres between the victim and treatment: for many Canadians, living in a rural area can pose a significant health risk.

Canadians who reside in rural areas are disadvantaged when it comes to multiple health-related measures, a 2006 report from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) discovered. It found that rural Canadians tend to have lower socio-economic status, resulting in a higher prevalence of adverse health behaviors, such as smoking.

The Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada’s website states that any aspect of an unhealthy lifestyle, such as smoking, poor eating and exercise habits, obesity, and alcohol and drug abuse, contributes to the risk of stroke. It says a stroke occurs when blood stops flowing to a part of the brain, damaging brain cells and resulting in detrimental effects ranging from paralysis to death.

A new study conducted at Université Laval has found that in-hospital mortality rates for stroke victims treated in rural hospitals is significantly higher than those treated in urban hospitals. Medical experts and the study’s authors are calling for action after results showed rural patients were approximately 25 per cent more likely to die from a stroke in-hospital.

Dr. Richard Fleet, the study’s lead researcher, is part of a group that works to improve research about rural hospitals and the training of rural physicians. Fleet said the main purpose of the study is to spark discussion about if Canadian health care is truly universal and to “get the ball rolling in terms of advocating for more services, better services” in rural health care settings.

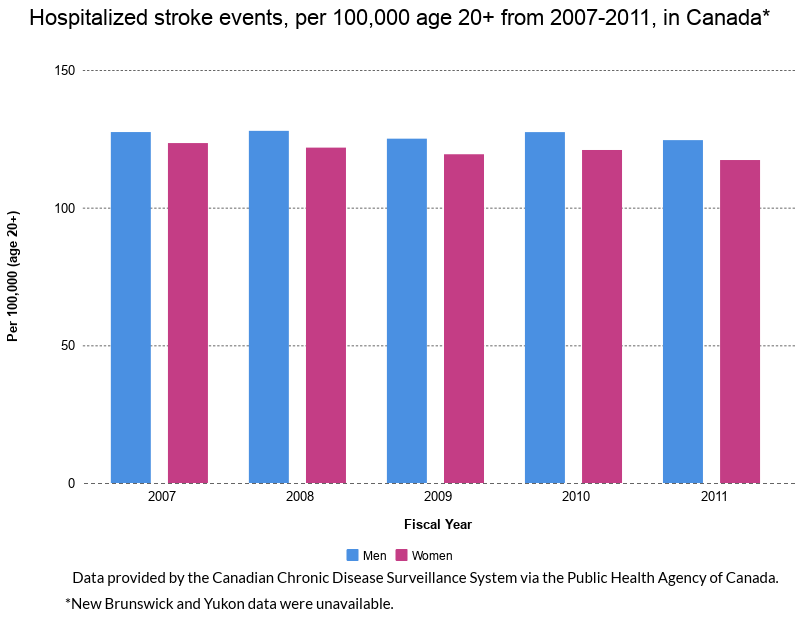

Using data gathered by CIHI from 2007-2011, Fleet’s team compared access to stroke diagnosis and care services across Canada, such as CT scanners and intensive care units (ICUs), in rural hospitals to those in urban hospitals.

The study defined rural hospitals as serving towns of 10,000 residents or less and analyzed those with 24-7 physician care and in-patient beds. Urban hospitals studied are academic centres with level one or two trauma centres which provided a wide-range of services to CT scanners, ICUs and speciality care, which Fleet called the “gold standard” of urban care. 286 rural hospitals met the criteria while the 24 urban hospitals that met criteria were used as a comparison point, he said.

Fleet said one of the main challenges was finding accurate data to adequately represent rural areas.

“There’s very limited research in rural healthcare and rural emergency care in Canada,” he said. “It’s quite surprising, and so, decision-makers need some data to inform them.”

Dr. Grant Stotts, director of the Ottawa Stroke Program, said Fleet’s study is important, “especially in Canada, where a considerable portion of our population lives in rural settings.”

“The discrepancy in stroke outcomes is important to recognize and improve,” Stotts said.

According to a Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada study published last month, 87 per cent of Canadians live within an hour’s drive of stroke emergency care. Though this statistic seems promising, it varies greatly when examined province-to-province. In Newfoundland, only 45 per cent of people are within an hour’s drive to stroke care. In Ontario, that figure sits at 97 per cent.

The Heart and Stroke study found that 69 per cent of Canadians nationwide have access to a service that operates at least five to seven days per week, and many services do not have adequate equipment to properly assess stroke victims. Fleet’s team also determined that access to CT scanners and intensive care units are critically limited in rural hospitals or missing entirely.

“A CT scan in an emergency department for urban emergency departments is kind of a basic tool nowadays,” Fleet explained. “Up to 20 per cent of everyone who walks through the door of an emergency department for evaluation ends up having a CT scan.”

According to Heart and Stroke’s website, a CT scan is used to determine the type and location of the stroke, and is vital for stroke victims to receive the correct treatment.

The Canadian Stroke Best Practice Recommendations, an advisory committee funded by Heart and Stroke and the Canadian Stroke Network, advocates for better treatment of Canadian stroke victims. In 2015, the network issued a report recommending immediate CT imaging for all acute stroke victims.

Citing this report, Fleet’s research team noted that the lack of in-hospital CT scanners in 89 per cent of rural hospitals “would hinder physicians from timely diagnosis of or administration of acute treatments when indicated.”

Based on recommendations from international guidelines and Heart and Stroke, Fleet asserted that the ideal treatment for potential stroke victims is to have a CT scan and have it interpreted within 30 to 45 minutes of symptoms, in order for doctors to provide quick and specific treatment. He called it concerning that this standard is often not met in rural hospitals.

“The first tool that should be maximized for rural settings that would assist stroke care would be 24-7 access to CT scanning,” Stotts said. “This includes physical machines, as well as funding for around the clock staffing.”

According to Fleet, many patients have reported bypassing rural health care centres and driving long distances to find stroke centres with adequate services. He said that on average, rural-dwelling Canadians are 200 kilometres from an urban emergency department or referral centre: a delay that could be fatal.

“Patients themselves should not drive long distances with anyone suspected of a stroke,” Stotts warned. “Since care is time dependent, treatment opportunities could be lost, especially if there is a misunderstanding of what is available locally and where they should go. This information is available to paramedics.”

Mary Wilson Trider is the President and CEO of the Almonte General Hospital in Ontario, a rural town with a population just below 5,000.

“Almonte General Hospital has an agreement in place which allows paramedics to bypass this hospital and go straight to a hospital in Ottawa with patients who meet the criteria for a stroke,” said Trider. The drive from Almonte to Ottawa is approximately 55 minutes on the highway.

Access to rehabilitation services following a stroke event are also problematic in rural areas. “Small hospitals in this region generally do not have sufficient human resources to support stroke rehabilitation close to home, such as physiotherapists, occupational therapists and speech language pathologists,” said Trider.

“All patients, regardless of whether they are urban or rural, would prefer to be cared for as close to home as possible in an environment that is familiar and close to their family and friends,” said Trider. “I think this is particularly true when the nature of their illness is serious and frightening, such as a stroke. It would be fantastic for the communities we serve if there were more resources available for the in-patient rehabilitation stage of their care to occur closer to home.”

Quebec and the Territories were excluded from the study due to limitations in the CIHI data. Fleet said another limitation of the study is the difficulty in determining the exact timeline of a patient’s stroke treatment. He said detailed data, such as the time at which a patient first showed symptoms, to when they were discharged from the hospital or died is not accessible.

“It is very complicated to obtain this information and it is quite costly,” Fleet explained. “It’s not readily available in databases, but that would be a really nice prospective study to discuss.”

Going forward, efforts are being made to improve stroke treatment data. The College of Family Physicians of Canada is working with the Society of Rural Physicians of Canada and federal health minister Ginette Petitpas Taylor to develop a “rural road map” to address rural health care issues.

Stotts said he would like to see improved telemedicine services and better training to local staff for stroke-specific aspects of hospital care. Telemedicine is the use of communication technology to widen access to healthcare in rural areas.

Through the Ontario Telemedicine Network (OTN), patients in rural areas can use apps and video calling to connect with out-of-area stroke specialists. In turn, those specialists can use the communication aids to monitor their patients. OTN has a special division called Telestroke, which connects rural physicians with stroke specialists during an emergency to ensure the best treatment plan possible is implemented.

“Initial stroke treatment with medications can be provided locally in a rural hospital through telemedicine with a stroke physician,” he explained. “This requires CT scanning capability and a telemedicine network. This has been established in Ontario and several provinces but is not nationwide, presently.”

Fleet added that his team’s study “may just be the tip of the iceberg” as to what Canadian citizens can do to “advocate, to study and to offer better standards for our rural citizens.”

“I’m hopeful that things will improve, but it’s going to take time,” he said.