“Do-it-yourself” Smallpox study renews debate on ethical concerns in scientific research

By Andrea Tingey and Nadine YousifA study published by a Canadian scientist in Jan. of this year has breathed new life into the age-old scientific debate of the ethics behind publicizing research that can be both useful and harmful.

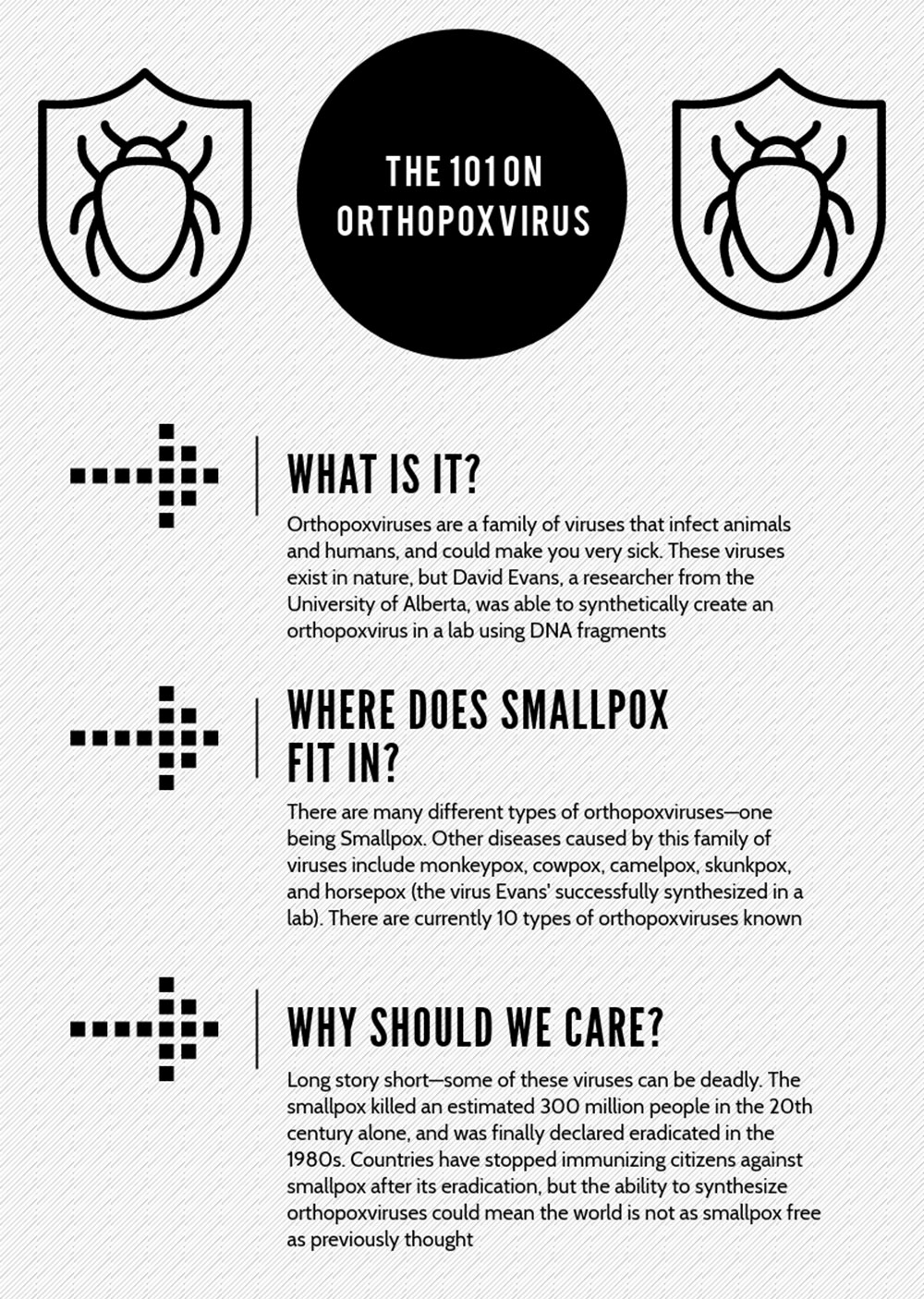

David Evans of the University of Alberta published a paper in PLOS, a popular peer-reviewed science journal, outlining the steps to create a synthetic version of the extinct horsepox virus, which is a cousin of the deadly smallpox virus. The rationale behind the research is to use this synthetic virus as a new vaccine against smallpox.

Today, vaccinations against smallpox are rare. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), no government gives the vaccine routinely as it could cause serious complications.

These complications are what prompted Evans and his team to research a new vaccine, according to Grant McFadden, a researcher and professor at Arizona State University. McFadden previously worked alongside Evans and the two have published papers together in the past. McFadden also sits on PLOS’ Dual-Use Research of Concern Committee, which green-lit the publication of Evans’ research.

The smallpox vaccine consists of the vaccinia virus, which has similar DNA to the horsepox virus. They all belong to the same family of viruses, orthopoxviruses. Because horsepox is extinct, Evans outlined in his paper the need to synthetically build it in order to test it as a potential new vaccine against smallpox. After exposing mice to the synthetic horsepox virus, the researchers found that they were protected against orthopoxviruses with minimal side-effects.

Evans declined to be interviewed for this story, stating in an email that, “there has been plenty said on this matter already.”

Critics of Evans’ research have voiced concerns about the possibility of the information falling into the wrong hands. Gregory Koblentz, an assistant professor at George Mason University who has written extensively on dual-use research, said his main concerns lay with the fact that the syntheses of horsepox can be applied to any orthopoxvirus, including smallpox.

McFadden, however, countered this argument by saying research that outlines synthetically created viruses was already available.

“Although the [dual-use] committee agrees that the technology can be misused by others, the technology pretty much already existed and it wasn’t a major advance technologically,” McFadden said. Indeed, research on how to synthetically build polio was published in 2002, and the Centre for Disease Control recreated Spanish influenza in 2005, which once killed as many as 50 million people in the early 20th century.

Behind the Research

Evans’ research was privately-funded by Tonix Pharmaceuticals, a company best known for a drug to treat PTSD. The PLOS paper was co-authored by CEO and co-founder Dr. Seth Lederman. Tonix declined an interview request, but according to McFadden, the company might be interested in patenting the designer virus in the case of it being licensed or sold as a product.

Koblentz, however, said the research is “based on a very weak business model,” as there is a limited market for smallpox vaccine that is dominated by the United States government, who has not expressed interest in a new vaccine but is rather focused on improving the vaccinations currently available.

“I don’t think it’s actually going to lead to the benefit or the product that they say it’s going to lead to, and so at the end of the day we’re left with all risk and no reward,” Koblentz said, and added “there is very little evidence” the syntheses of the horsepox virus would make a better smallpox vaccine.

Lack of Oversight

Koblentz said he is also concerned with the lack of biosecurity oversight or overview prior to the publication of this research, mainly because it was funded by a private company.

“[The publication of Evans’ report] legitimated doing this kind of research without having to get approval from a national government or the WHO for that matter, and being able to do this in a way that is almost completely unregulated,” he said.

Koblentz added the WHO, DNA synthesis companies, and the scientific community need to take joint responsibility in overseeing the synthesis of orthopoxviruses.

“The research needs to be monitored and approved in a way that scientists and governments are confident that the benefits of this research outweigh the risks,” he said. “That conversation needs to happen before the research takes place, that did not happen in the case of Horsepox syntheses.”

David Knutson, a spokesperson for PLOS, said a considerable amount of deliberation went into the decision to publish Evans’ research on the recreation of the smallpox virus. The journal adheres to a 14-point checklist that deems whether an article is safe to publish.

“We reject 50 per cent of the articles we get because when they go through our 14 technical and ethical checks there’s something in there that’s missing,” Knutson said, adding that PLOS publishes about 30,000 articles a year.

From there, McFadden said the PLOS committee discussed the potential implications of publishing this research. The committee only meets on a case-by-case basis, which usually amounts to just a dozen times a year. These meetings take place primarily over email.

McFadden said the WHO wants a safer smallpox vaccine and effective antiviral drugs before the destruction of the two existing samples. But Evans’ research proves that destroying these samples won’t free the world from the threat of the virus: it can be created in a lab.

McFadden first saw Evans’ research while sitting on the WHO Advisory Committee on Variola Virus Research in Geneva, Switzerland in Nov. 2016.

“The only thing I remember is thinking to myself, ‘I wonder what took the field so long to actually make a virus from scratch?’” McFadden said.

McFadden said that though the controversy surrounding Evans’ research was unjustified, we could see more of this in the future.

“I think synthetic biology is here to stay and will only grow in the future,” he said. “The day will come when probably people will synthesize viruses that they want from scratch simply because it’s easier to get it.”

The Future of Dual-Use Research

This isn’t the first time dual-use research has caused a stir in the scientific community. Similar conversations surrounding ethics of publication rose to the surface in late 2011, after the journal Science and Nature published an article where researchers modified the H5N1 virus, also known as avian flu, and proved that it could be transmitted between mammals.

The discovery stirred debate about whether or not the journal should have published the results, and PLOS’ own DURC committee was formed as a result.

“It really set a number of journals off to realize they need to take DURC seriously,” McFadden said of the controversy.

The Canadian Institute of Health Research formed a sub-committee in 2017 to address new technologies through the lens of DURC. The focus remains on creating material to raise awareness and educate peer reviewers and applicants.

PLOS has taken steps to address the controversy. They’ve asked four experts, including David Evans, to write opinion pieces about the horsepox article, which will be published in an upcoming journal.

McFadden teaches his students at Arizona State University about the H5N1 controversy. Students prepare arguments for and against publishing the paper. One thing he’s noticed?

“The class never votes in unison.”