Eye on the sky

The past few years have been the safest in aviation history but researchers are working to ensure that the individuals making decisions in the cockpit are ready for anything.By Caroline O’Neill, Catrina Smyth, Christine Vezarov

By mid-afternoon, the January skyline was speckled with a few clouds, giving a clear view of New York City’s Hudson River.

At 3,000 feet up in the air, the cockpit’s view of the blue sky was suddenly blocked by a flock of Canadian geese. Loud bangs pierced the cabin, flames engulfed the engine and the scent of fuel filled the plane. As both engines shut down, Captain Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger pulled off an emergency landing that saved the lives of every passenger and crewmember aboard his plane.

“He 100 per cent successfully ditched his aircraft because he practiced it a thousand times in a flight simulator,” says Dr. John Hayes, a co-creator of Carleton University’s Atlas flight simulator, that trains pilots to react to different emergencies and conditions they could experience during a flight. Dubbed the “miracle-on-the-Hudson,” scientists like Hayes find nothing miraculous in Sully’s emergency landing. Brave and life–saving? Yes. But more importantly, the result of training and preparation that aim to make these kinds of reactions the norm.

Hayes is among the experts who rely on data like those in the Aviation Safety Network’s annual report, a worldwide collection of the crashes and causes by year.

“I used [this specific study] for a rationalization,” says Hayes who refers to ASN’s data when applying for grants.

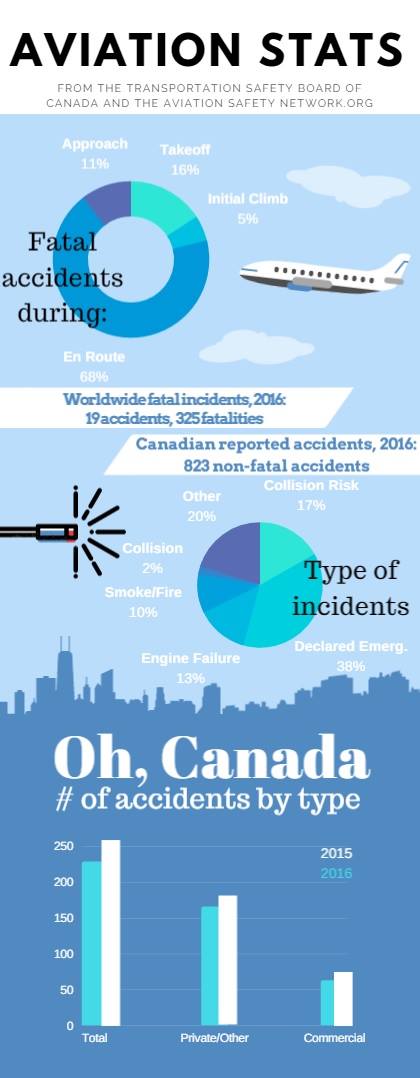

The data show that 2016 was the runner-up for the safest year in commercial aviation, with only 19 crashes resulting in 325 fatalities out of 3.5 billion travellers,. The top ten safest years all occurred in the second millennium, with 2015 awarded the gold medal, according to the World Bank.

To passengers who essentially hand over their lives to the pilot, plane and crew, such encouraging numbers don’t always negate fear. The disaster scenarios are all too easy to imagine: An aircraft can hit a mountain. A weapon might mike it through security. A pilot may suddenly act irrationally, endangering everyone on a flight.

To better understand the reality behind the numbers, Catalyst reporters spoke with professionals who are navigating the complex systems and the occasionally morbid realities that underly modern aviation.

Preparing for the unpredictable

Hayes’ lab at Carleton University aims to replicate the exact conditions a pilot might experience in the worst case scenario.

“Of course, [pilots] crash many times in the flight simulator – but zero risk,” he says.

Unlike other platforms, which seat the cockpit on six height-changing legs, Hayes’ flight simulator sits on “omni wheels” with castor rollers that individually swivel. This design allows for a wider range of angular displacements including those needed to simulate circular flight trajectories, Hayes says.

Yearly reports, like those provided by the ASN, show how regulatory bodies are doing their jobs to ensure that the mechanics, from radio towers to a plane’s rivets and permanent fasteners, are properly monitored. Ensuring each individual component of the system is performing, like the inner workings of a clock, is no small feat. Even though each country navigates their systems differently, Hayes says that most mechanical failures are actually random.

“People are very nervous flying, and I used to be that myself before I started working at Aviation and learning a lot more about how aircrafts work and the standards that are in place,” said Erin Greggory, the Canadian Aviation and Space Museum’s assistant curator and a reformed white-knuckler during in-flight turbulence.

“Each aircraft crash since the earliest days of commercial aviation has resulted in some sort of legislation or policy … that has improved the safety,” she adds.

Looking back at history’s skyline since the Wright Brothers first flight in 1903, Greggory says every plane crash due to a mechanical failure has provided sobering opportunities for improvement.

The system that entrusts regulatory agents around the world is not perfect, she notes. But scientists like Hayes are using technological advancements and lessons from aviation history to help plane safety keep soaring.

Fit to fly? The human factor

“When you’re a pilot, your medical is everything,” says Simon Garrett, a veteran flight instructor and examiner at the International Pilot School in Carp, Ontario. “When you lose your medical, you lose your job— your career.”

Pilots must complete routine, basic medical examinations to ensure they meet health standards. The tests are likened to head-to-toe check-ups. Legally, when a pilot goes to see a doctor, he or she is required to state that they hold a pilot’s licence.

“There have been times in my life where I’ve been afraid to go to the doctor and say I’ve got something wrong because I don’t want to risk losing my medical,” the pilot says, looking back at his 45 years of experience. “I will not take any sort of drugs unless I’m absolutely in agony. Not even an aspirin or Advil because I will not risk, in any way, shape or form, creating a dependency.”

“There have been times in my life where I’ve been afraid to go to the doctor and say I’ve got something wrong because I don’t want to risk losing my medical.”

After every doctor’s visit, the appointment details, results and notes are filed to the pilot company’s physician.

“If you’ve got a doctor who’s looking after, as they should, the best interests in aviation, and they have the slightest concern— they’re going to say that you’re not flying until you sort this out,” says Garrett, who has won multiple awards in pilot health and safety.

This is best-case scenario, however, it isn’t a catch-all, he says.

The reality is that some health issues won’t be flagged unless the individual comes forward about it. Mental health is one of these areas that, just like cognitive ability and skill level, isn’t assessed as time goes on, Garrett says.

“You know men, they’re not going to admit anything until the very last minute,” he jokes. “If they think they’ve got something quite serious, they’re not going to go to their civil aviation medical doctor.”

The system has cracks. While it is not easy to do so, it is possible for a pilot to manage to hold on to their a licence to fly even after failing a health health exam, Garrett says.

The Germanwings crash in 2014 shifted public discourse to the ‘human factor’ — the people flying the plane.

It was known that the pilot, Andréas Lubitz, had been treated for suicidal tendencies and had seen multiple doctors, Garrett said. But no action was taken. Three years later, the incident continues to highlight the need for a more holistic approach to pilots’ health.

“You are putting your trust in someone else to get you from point A to point B,” says Greggory.

“I tend to trust the machine more than the people operating it.”

Overall wellbeing can be just as hard to predict as an unforeseen mechanical failure.

“You can pass a medical today and tomorrow die of a heart attack,” Garret said, highlighting the difficulty in measuring all aspects of health empirically.

“I tend to trust the machine more than the people operating it.”

It’s not a single factor, such as age, that will necessarily determine the result of a standardized medical exam. Rather, a well-rounded examination is needed, Garrett says, one that assesses mental, cognitive, emotional and physical capacities.

And while this all-encompassing approach might not be in place yet, researchers continue to make strides.

“A pilot doesn’t forget how to fly or where they’re going, but they might forget to do something important in the future,” says Dr. Kathleen Van Benthem, a post-doctoral fellow at Carleton University’s Advanced Cognitive Engineering Laboratory.

Her research uses an old plane’s cockpit and a moving screen to simulate a flight, examines cognitive responses in aging general pilots. One hundred pilots aged 19-81 from Eastern Ontario have flown in this simulator, with different conditions thrown their way.

Van Benthem collects data on regular cognition like processing or memory, as well as cognitive skills specific to aviation. One factor, for example, is prospective memory: the pilot’s ability to remember things they should do in the future, like making radio call.

“We do not believe that there is one age where people should stop flying,” she says. “We want to develop resources to keep people flying longer, but safer.”

Flying into a safer future

Planes continue to be the only transport method to take passengers through time zones in a little more than a day. The complex systems regulating how and when they are flown are not perfect, but researchers are looking for new ways to keep pilots prepared for any turbulent situations.

For Hayes, this means ensuring his one-of-a-kind simulator offers as many different iterations of a disaster as possible. A stall, when a plane doesn’t have enough lift, can manifest itself in different ways, he explained. The Atlas Project aims to allow pilots to experience free falling.

Creating a conversation around plane safety with the public is another way to talk about reports, tragedies and research. But it can often be risky territory.

“It is a touchy subject,” says Greggory. “We don’t want people to have a negative experience when they’re here.”

The aviation museum did an exhibition called Safer Skies that analyzed potential causes for crashes. Fear can be combatted by being factual, neutral and avoiding dramatics, Greggory says.

Van Benthem’s approach to the future is to develop a cognitive health-screening tool that is unbiased against age. There is a time for individuals to stop flying, she acknowledges, but adds that she doesn’t want pilots’ to be grounded unnecessarily.

Another look-ahead for pilot training might include virtual reality goggles, which are more accessible and cost-effective than flight simulators, Van Benthem said. In augmented realities, a pilot’s senses are engaged to feel factors like turbulence, an altitude stall or hearing a radio call. Van Benthem foresees both virtual and augmented realities as ways to keep pilots in controlled, safe zones that are as near to true conditions as possible.

As 2015 and 2016 sit side-by-side as the safest years in aviation history, the next years could easily plummet or take flight to recent innovations.

Just as random acts can change an entire flight’s course, life’s circumstances might also be the reason many people will need to fly, whether they want to or not.

Van Benthem remains optimistic about flight safety in 2017 and beyond, and offers some advice for the worried:

“Don’t be scared to fly.”