Flu pandemic preparedness in the age of social media

Ottawa Public Health leads the pack

By Emma Rektor and Alexandra Elves

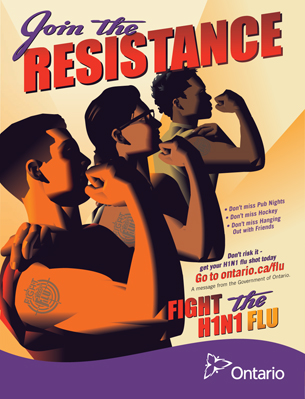

In March 2009, reports from Mexico of a new strain of influenza had health officials in Canada on high alert. By the end of April, there were more than 100 cases in seven different countries and seven people had died from the new mystery flu. Canada did not escape its wide reach, as people began to fall ill across the country. The first death in Ontario, in late May, came a few weeks before the World Health Organization declared H1N1 a worldwide pandemic.

The virus, colloquially called swine flu, was something new and had developed by chance in Mexico.

A study led by researchers from Mount Sinai Hospital would eventually discover that the virus had jumped between pigs, birds, and people, gaining new genes along the way. When this chimera virus infected people, it spread with alarming ease, their immune systems no match for the new bug.

Public health officials in Canada tracked the evolving situation and shared that information with Canadians.

In Ottawa, wait times for some vaccine clinics around the city spiked. People waited upwards of two and a half hours for inoculation at some sites; others faced no delays.

That is when Ottawa Public Health sent out its first tweet, a foray into the world of social media, in order to better disperse people among vaccine clinics across the city. Throughout the epidemic, the City posted frequent Twitter updates to keep Ottawans informed on expected wait times at clinics. The account grew rapidly in popularity, to the surprise of public health employees.

Ten years later, this surprise seems dated. The prevalence and impact of social media in our society has changed drastically. As people increasingly turn to social media to find and share information, public health organizations are trying to use that to their advantage while simultaneously navigating through roadblocks – such as those posed by the spread of misinformation – to a varying degree of success. As a future flu pandemic is inevitable, are governments and public health organizations prepared? Experts say Ottawa Public Health is a municipal leader in Canada but must remain vigilant as social media intensifies long standing challenges.

A solid communication strategy is the most important public health intervention during an emergency, experts universally acknowledge. By the same token, there are many opportunities for communications to go awry.

One major challenge is combating the spread of misinformation. The H1N1 pandemic marked the beginning of a “dark decade for science communication,” said Timothy Caulfield, a law and public health professor at the University of Alberta. Social media algorithms enhanced echo chambers, where people surround themselves entirely with ideas they already agree with, regardless of whether they are supported by science. In turn, social media helped spur the erosion of public trust in traditional sources of information and it boosted the influence of celebrity voices promoting pseudoscience.

An increase, often sudden, in the number of cases of a disease than is typical in a certain area. [CDC]

An epidemic that has expanded to multiple countries or continents. [CDC]

Information that is not true, but created and shared without malicious intent.

Information that is not true, but created purposefully to deceive and cause harm.

Studies have shown a “powerful anecdote will overwhelm the available evidence,” Caulfield said. He thinks the spread of misinformation through powerful narratives is one of the biggest challenges science communicators face.

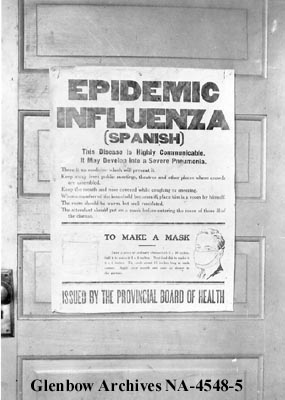

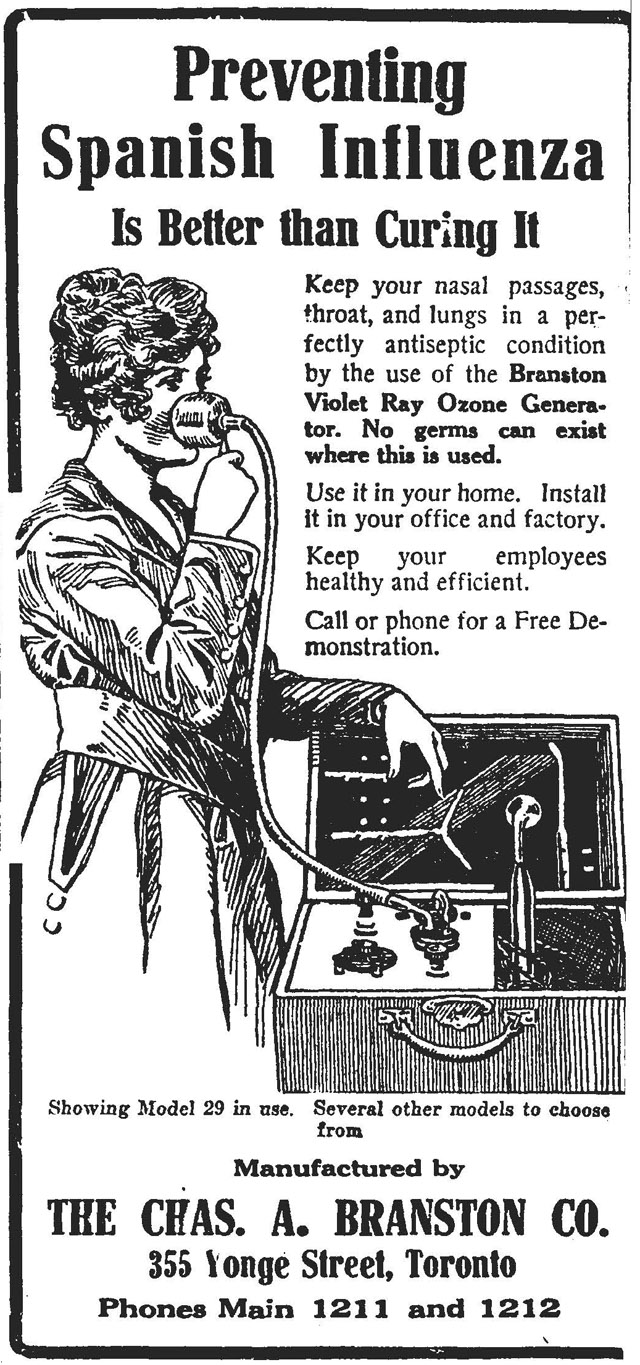

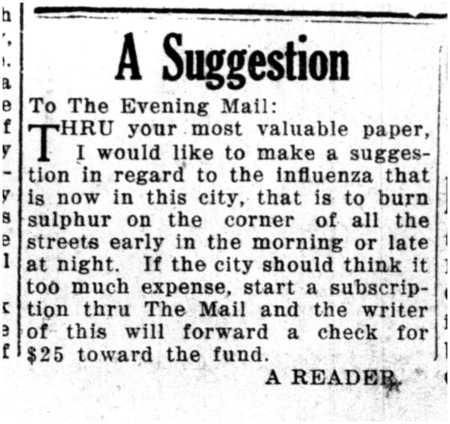

If a new pandemic arrived today, Caulfield said he expects the people already spreading misinformation would be “very energized,” but that surprising voices could also pop up. For example, he said “horrible lies” circulated about how to prevent and cure HIV/AIDS. That epidemic started about forty years ago, but organizations are still fighting harmful myths such as the idea that having sex with a virgin will cure HIV.

Caulfield emphasized the need to use “creative communication strategies,” to combat misinformation. The strategy could include the use of narratives, art, and data visualizations.

This new strategy wouldn’t necessarily require massive investment in training either. Caulfield said not everyone wants or needs to become an expert in social media and creative communication. Rather, he said it’d be better to support those who already have the interest and skill set to grapple with the misinformation beast.

Another challenge, according to Tracey O’Sullivan, Ottawa University professor in the Interdisciplinary School of Health Sciences, is communicating health information in a way that gets the public to take the right action. Messaging must strike the balance between causing panic and causing complacency, said O’Sullivan.

In Canada, the diversity of the population also creates a particular challenge. There are people who live in rural and remote communities, where Internet service is slower and less reliable. There are also groups of people who don’t use social media, such as many older Canadians or those who cannot afford a smart phone, computer or Internet service. Compounding accessibility issues, the 2016 Statistics Canada census found that nearly eight million people have a mother tongue other than English or French. Social media offers infinite space for the same message in various languages and formats, but tailoring messages takes time and investment in people who can do so, said O’Sullivan.

When developing a plan or a strategy, health authorities must avoid widening any existing disparities said O’Sullivan. For example, hand washing is a common measure likely to be promoted during an outbreak, but such messages assume the reader has access to clean, running water and not all Canadians do. In that situation, people require information on alternative actions they could take.

In a pandemic, social media isn’t just useful as a way to disperse information but also as a way to acquire it. No longer do governments and public health organizations simply issue directives to the passive masses. Citizens share their opinions and fears, details about their day-to-day lives – all of which will inform and mould a response in real-time as the pandemic plays out.

For example, public health officials could monitor social media platforms during a pandemic to note and nip misinformation in the bud, before it went viral. “Social media has a capacity to help people in that respect, in terms of alleviating fears or correcting misinformation,” said O’Sullivan.

This approach relates to what Marcel Chartrand, professor of communications at Ottawa University, refers to as the importance of centralizing information. To save individuals from having to sort through and try to identify for themselves what information is correct and useful, a system should filter and aggregate for everyone.

How could this be done? Chartrand envisions the establishment of a single hashtag, which governments, public health organizations, and the public alike could follow to stay up-to-date on all the latest developments.

According to O’Sullivan, Ottawa Public Health is doing “a really good job,” at leveraging social media and avoiding its pitfalls. That is because, O’Sullivan said, the organization has been very successful at building and engaging its audience.

Eric Leclair, manager of communications at Ottawa Public Health, points to a large following on Twitter as a reason Ottawa Public Health is a leader in the field nationally. The @ottawahealth account as of publishing this article has over 59 thousand followers, which is over 23 thousand followers more than the Toronto Public Health account, a city with nearly three times the population.

Leclair credits the large social media following, which extends to Facebook, to being early to the platforms and creating relatable and approachable content.

“We keep it very personal and we make sure that we’re very responsive. If somebody wants to engage on social media, they know that somebody is going to reach back out and contribute to the conversation,” Leclair said.

On Twitter, the organization supplies followers with some enjoyable aspects of social media, he said.

“We use those engagement tools like humour and pop culture to get people to listen and engage so that when we do have a big message people are there and they’re seeing it,” he said.

This use of humour separates the Ottawa account from other government accounts, where fears of making mistakes results in more bureaucratic, dry posts.

The post has not been looked at “by seven different layers of approvals and it’s become so stale and dry that it just doesn’t resonate,” Leclair said.

In an emergency, however, all other messaging stops as targeted emergency-related messaging starts, Leclair added. Followers are likely to turn to the organization’s account to save time during an emergency, he said.

Leclair points to the 2019 Westboro bus crash as an example of a recent successful emergency communications response. In the aftermath of the bus crash, residents could turn to the @ottawahealth account for mental health services information.

Leclair feels confident in his team’s ability to respond during the next pandemic but recognizes the need to stay vigilant as new challenges arise. Although Canada has made vast improvements there is still potential for growth as social media is under-utilized by some government organizations.

While a Canadian federal guidance document explicitly mentions the need to counter misinformation, neither Ontario’s pandemic plan nor the City of Ottawa’s emergency plan does.

It’s hard to predict how Canada will fare when the next pandemic hits, O’Sullivan said, but there is a well-developed understanding of what needs to be done and the country has put consistent effort into preparing for this eventuality.

This effort is paying off, as Canada ranked fifth out of 195 countries in the 2019 Global Health Security Index which evaluates countries’ ability to deal with health emergencies, including disease outbreaks. Still the report notes, “no country is fully prepared for epidemics or pandemics, and every country has important gaps to address.”