The public policy toothache

Fluoridation remains controversial even though it is the only free public health measure available for tooth decay prevention

By Meredith Lauzon, Dylan Parobec, and Daanish Rehman

“I never would have envisioned [fluoridation research] would lead to this many questions that I felt needed to be answered.”

Fluoride isn’t just found in your toothpaste; it might also be in your water. In Ottawa, it’s step eight on the city’s ten-step water treatment process, added to protect the public from the common affliction, cavities.

Yet not everyone is convinced the chemical should be part of the public water supply. Fluoride’s presence in Canadian drinking water has waxed and waned over the past few decades–sometimes because of the cost of fluoridation, sometimes due to fears about its health effects—fears that are unsubstantiated, according to Health Canada. Fluoridation is an “important and often overlooked public health measure,” and it remains the “most cost-effective and equitable” way to prevent cavities on a population level, the agency notes on its website. But the controversy hasn’t ebbed. In the wake of fluoride removal from some Canadian municipal water supplies over the past decade, new public health research suggests cavities are on the rise – motivating officials in some cities without fluoride to rethink its elimination.

Fluoridation’s Canadian History

In Canada, fluoridation of public water began in Brantford, Ontario in 1945. Community water fluoridation hit a country-wide peak in 2007 at 42 per cent. Health Canada regulates the optimal level of fluoride in water at 0.7 milligrams/liter, a measure Public Health Agency of Canada attributes to a 25 to 30 per cent reduction in tooth decay.

But over the past decade, the practice has waned. The most recent survey by the Public Health Agency of Canada, performed in 2017, showed fluoridation levels at 39 per cent across the country. The drop comes as municipalities across the country began discontinuing fluoridation, with the largest change happening in Alberta. In that province, the practice dropped from 74 per cent in 2007 to 43 per cent in 2012, where it remains today. This plunge is largely due to Calgary’s removal of fluoride from their water after which other municipalities in the province followed suit.

In late February, Calgary city council broke from their previous stance and motioned to review fluoridation research. The move was motivated by public health researcher Lindsay McLaren and her colleagues at the University of Calgary who found a correlation between removal of fluoride and an increase of cavities in the city’s children.

McLaren has spent eight years studying fluoridation, starting when Calgary removed it in 2011.

She said the decision to remove fluoride from Calgary’s water was partially motivated by the arguments of anti-fluoride advocates, and for financial and social reasons particular to Calgary. In addition to the yearly operational costs of fluoridation of about $750,000, the city’s infrastructure required a $6 million upgrade, McLaren said. In 2010 there was a municipal election that led to council turnover. When a motion was brought forth to stop fluoridation as a way to reduce costs and because of concerns with its safety, it was accepted. The motion included a resolution to redirect the funds saved from halting fluoridation to dental care for low-income children. It is unclear whether that plan was put in place and/or whether it helped on a large scale because of the increasing demands for dental care for disadvantaged families in Calgary. To some, this decision is surprising, but not to McLaren. She said Alberta’s largest city only adopted the fluoridation in 1991, and never had strong public support for the practice.

Fluoridation and Health

In February 2019, the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, an independent, not-for-profit agency that conducts systemic analyses of issues in health care published a report on the possible health outcomes of municipal water fluoridation in Canada.

Examining six decades of data, the organization found no evidence or insufficient evidence to associate fluoridation with poor health outcomes. In particular, the report found “no association between water fluoridation at the current Canadian levels and bone cancer, total cancer incidence, hip fracture, Down syndrome, and IQ and cognitive function.” Other systemic analyses come to similar conclusions: Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council found that “water fluoridation is safe and effective in helping to prevent tooth decay in the ranges recommended for use across Australia” and “does not cause harm.”

Such reports have done little to dampen the energy of anti-fluoridation lobbyists.

One of the most prominent voices in opposition of public water fluoridation is Paul Connett, the acting director and co-founder of Fluoridation Action Network (FAN), located in Binghamton, New York.

“From a scientific point of view no one has ever demonstrated that we need fluoride as a nutrient,” said Connett. “The one tissue that may benefit from topical fluoride is the teeth, but this is a topical mechanism, it reacts on the surface of the tooth, not from inside the body.”

Connett said he is concerned about the biological effects that fluoride might have when ingested in the water supply. He points to a 2017 study that examined fluoride exposure on prenatal and childhood neural development in Mexico, the work of University of Toronto researcher Howard Hu and colleagues.

The study, published in Environmental Health Perspectives, found that among 299 mother and baby pairs in Mexico, “higher prenatal fluoride exposure was associated with lower scores on tests of cognitive function in the offspring.”

When the study was published, the study’s main author Hu told National Post that “there still may be a level of fluoride exposure among both pregnant women and everybody else that can still preserve the beneficial effects on tooth decay, while avoiding any effects on intelligence.”

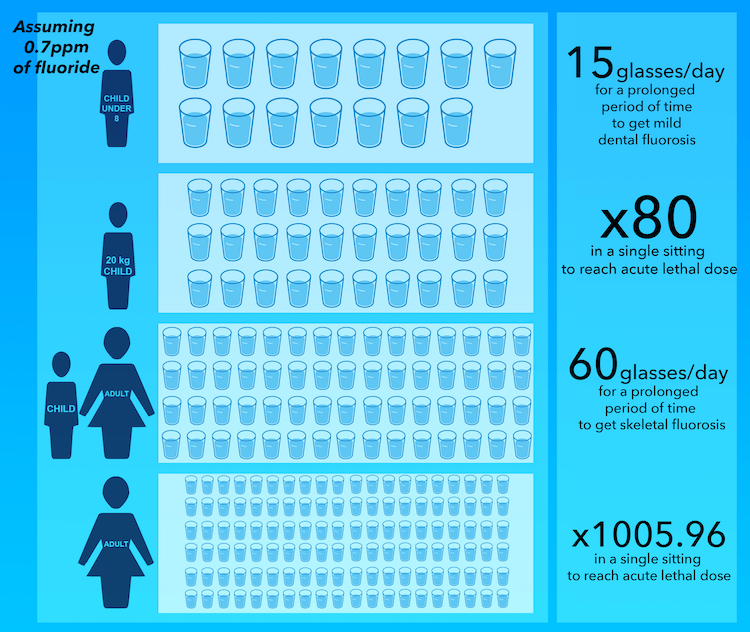

Data visualization by Daanish Rehman

Data source: Community Water Fluoridation presentation by Dr. Khalida Hai-Santiago, DMD, Oral Health Consultant http://www.wrha.mb.ca/healthinfo/preventill/files/HSHC-Presentation-02.pdf?fbclid=IwAR1MrGyEh54YiUdbb5B_yskFK9_gEZRrEUsPG3JHdCHglVWepZPz2xJoZdM

In an email to Catalyst, Hu added that more research needs to be conducted on the long-term effects of fluoridation exposure, but that he’d prefer to “let debaters and policy makers conduct the discourse.”

Public health researcher McLaren said Hu’s paper and others are “important, peer-reviewed contributions to this field.” She adds that research isn’t static–it’s important to continue researching to be able to recommend the best public health options that consider all potential benefits and harms.

In that regard, systematic reviews of all available studies are important for informing public policy. Systematic studies, McLaren said, gather all the individual studies together, assess methodological strengths and weaknesses, and evaluate overall relevance. “For example, sometimes studies focus on levels of fluoride that are very high, which would not necessarily be relevant to community water fluoridation per se.”

At the levels Health Canada recommends, McLaren does point out that fluoride can occasionally cause a cosmetic condition–discolored patches on teeth. This condition, called dental fluorosis, might be considered an adverse outcome because people’s appearance affects their wellbeing, said McLaren. But she said there is no robust research to suggest that there are other adverse health outcomes at the recommended level of fluoride in Canadian drinking water.

Fluoridation and Dental Care Coverage in Canada

Fluoridation prevents tooth decay in three ways, McLaren said. It enhances tooth remineralization by building up the protective enamel on teeth, it prevents or slows down the process of tooth demineralization, and consuming it through fluoridated water means that there is a low level of fluoride in your saliva, which helps fight the bacteria causing tooth decay.

The bacteria that cause cavities disrupt the tooth’s structure, causing weak spots, explained Ottawa dentist, Dr. Asal Hashemi. Fluoride helps strengthen those weak spots to prevent them from worsening in to cavities. Once a cavity is formed, fluoride cannot undo this decay and dental intervention is necessary – and is often costly.

In Canada, only “medically necessary” dental surgery is covered by universal health insurance plans. This does not include preventative visits like fluoride services or cleanings.

In a study on the Canadian dental system published by the C.D Howe Institute, Carleton University public policy researcher Frances Woolley found that, “dental problems are strongly correlated with income.”

Although all provinces have some dental programs for low income individuals, the coverage is often patchy. Cavities can take months to a year to manifest, and depending on the province, the available programs for low income recipients may only provide coverage assistance after major dental problems have developed, as shown by the C.D. Howe Institute.

For comprehensive coverage, people typically rely on employer-based dental programs that are often only available to full-time employees. This poses a concern for those in the “gig economy” that do not receive benefits, and the soon-retiring baby-boom generation, the C.D Howe study indicates.

McLaren said it’s hard to imagine a viable public health alternative on par with fluoridation—studies consistently conclude that it is a cost-effective way to prevent cavities. In an ideal world with fewer budgetary restraints, McLaren could envision large-scale campaigns to promote oral hygiene or universal dental care system.

“But those types of initiatives, especially if we are talking about dental services, they are just orders of magnitudes more expensive than fluoridation.”

As many municipalities evaluate whether to fluoridate their water or not, McLaren wishes the debate wasn’t filled with such contention.

“I feel like that’s not very constructive and it’s to the detriment of the people that it is so polarized.”