Jules Blais: Finding a solution to accidental oil spills

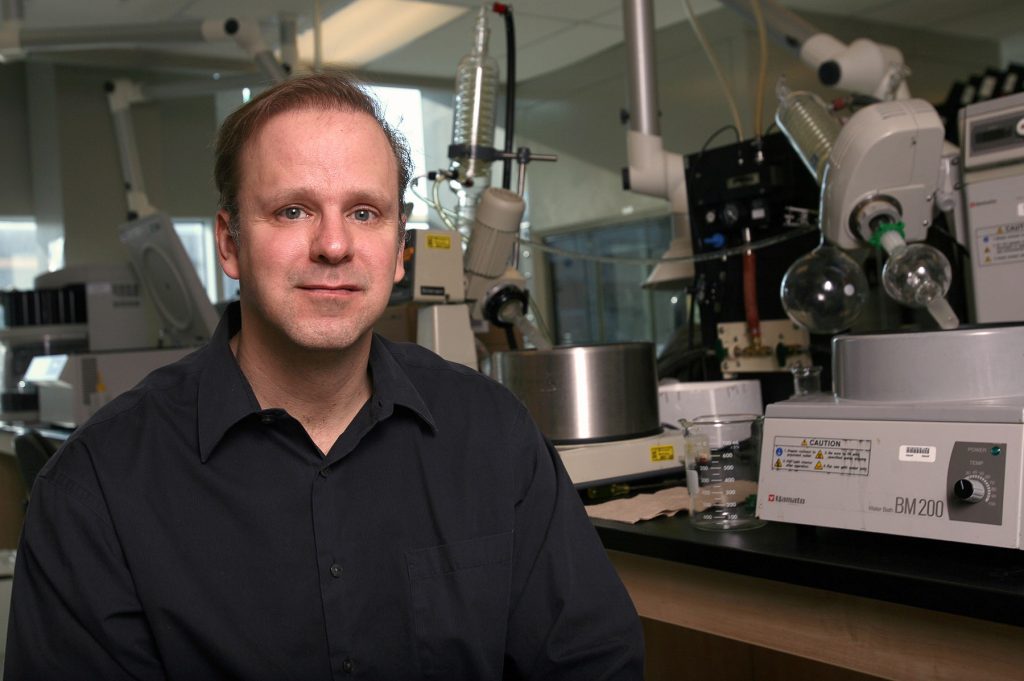

Biologist Dr. Jules Blais sits at a cluttered desk scrolling through what looks like an endless list of emails. Beside him, an antique lamp perches atop a bookshelf, brimming with copies of scientific papers and academic journals. The glow of the computer screen, the only source of light in the cramped fourth-floor office, reflects off the surface of his thin, square glasses.

But while the scene may convey the look of a cloistered academic, Blais’ scientific work is neither abstract nor confined within the walls of his fourth floor office at the University of Ottawa.

Blais is currently in the midst of planning an experimental oil spill in northwestern Ontario with his research team in order to better understand the harmful effects of diluted bitumen in freshwater lakes.

An expert at environmental pollution, Blais is currently planning an experiment in northwestern Ontario in which he and his research team will intentionally dump bitumen into a small lake to better understand the harmful effects of bitumen on freshwater ecosystems.

Blais believes his experiments will have implications for the ways in which Canada regulates oil transported through pipelines.

Blais grew up north of Montréal in a town called Rosemère, known for its rolling hills and fallow farmland. He said his interest in the environment, especially pond life, grew out of the surrounding landscape.

“Kids didn’t play video games back in those days and there were no screens except for a TV that had two channels so I was outside a lot.”

What started out as childhood curiosity about life underwater, turned into a Bachelor’s degree in biology from Concordia University. As a student enrolled in a PhD program at McGill University, he studied biogeochemistry and, more specifically, limnology, better known as freshwater science.

“I was interested at the beginning in metals and how metals behave in water,” Blais said. “What are some of the natural processes that can lead to high concentrations of metals?”

Unbeknownst to Blais at the time, that initial research question would open the door to a long and successful career spent tracking the reach of environmental pollutants around the globe.

Along the way, a key influence was renowned environmental scientist David Schindler, who teamed up with Blais on his post-doctoral thesis.

“We were interested in looking at organic pesticides and [polychlorinated biphenyl], and how they move through the environment,” Blais said.

Their research would lead to the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, an international treaty signed in 2001, which tried to eliminate or limit the production and use of persistent organic pollutants.

“He has a really strong background in a variety of different fields, and he’s always willing to push the boundaries of his own expertise in order to work on interesting questions that have important implications for aquatic ecosystems and even human health, in some cases,” said Joshua Thienpont, a postdoctoral researcher who works with Blais at the University of Ottawa.

The beginning of a promising mentor-mentee relationship

Thienpont first met his mentor while he pursued his master’s degree, and together they worked on a larger collaborative research program, co-led by Blais and his students. Then, shortly after, Thienpont joined Blais’s research team, and continues to conduct research directly under his supervision to this day.

Thienpont and Blais have teamed up to work on a number of different projects: “They range from assessing the legacy of impacts to aquatic ecosystems from contaminants around the Giant Mine site in Yellowknife and contaminants in the Peace-Athabasca Delta ecosystem of northern Alberta, downstream of the oil sands, to the impacts of in situ oil sands extraction in Cold Lake.”

Thienpont says their goal is to understand the natural environmental burden of different contaminants in advance of any potential development in that area.

Thienpont also says he owes a lot of his success in his academic field of choice to Blais’s guidance and tutelage.

“I think one of the defining feature of Jules and his research is that he’s not afraid to try new things; to look at new problems that maybe haven’t been assessed before or in new ways,” Thienpont said.

Blais’ experiment breathes new life into scientific research on oil spills

Blais and his ever-growing research team went on to study and date ancient deposits set in sediment cores. An example of their work took place at the Giant Mine in Yellowknife, where they examined an excessive amount of toxic arsenic that had been released into the environment.

“People were wondering if it was natural or if it was because of the mine,” Blais said. “There was high sulfur and that could explain why there was high arsenic.”

His team used relatively basic information, such as when the mine opened and closed, to measure the levels of arsenic underground.

“We were able to basically show the history of arsenic contamination in the sediment core and how it related to the mine,” Blais said. “This was clear evidence that the contamination was coming from the mine, it wasn’t natural.”

“What these kinds of archives allow us to do is extend that history of environmental change back sometimes thousands of years,” Blais added.

Blais was able to use this process to answer a hotly debated question related to the Alberta oil sands: “How much of these hydrocarbons have been released by human activity versus how much is there naturally?”

Blais and his research team studied the composition of these hydrocarbons that have been deposited at the bottom of freshwater lakes to determine how it has changed in relation to human activity.

The Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) agreed to greenlight their proposal to study the effects of oil on water.

This summer, in one set of experiments, Blais and his research team will add diluted bitumen to enclosed columns of lake water and then examine how this oily residue breaks down as well as what happens to the surrounding wildlife, including algae and fish.

Blais said he hopes his research will inform the national pipeline debate and inspire a solution to accidental oil spills in freshwater environments.

“It may look like we are doing something very nasty by adding some oil to water, but the goal here is to improve our regulations of the oil sector and make large-scale improvements to water quality, which I think can happen globally,” said Blais.