Passing down history:

How our biology may play a role in the transmission of trauma

By Alexandra Vegso and Jessica Mundie

External modifications to our DNA, called epigenetic changes, may play a role in passing trauma from one generation to the next. Researchers studying these modifications hope to develop new strategies for Indigenous communities dealing with residential school trauma.

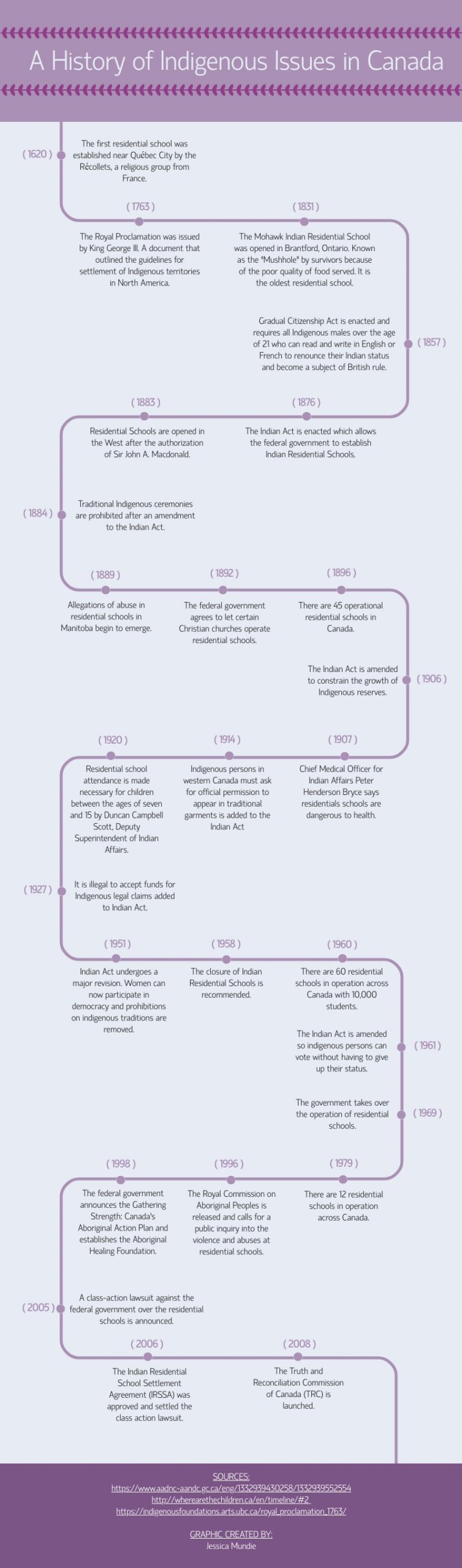

From the 1870s to the 1990s, thousands of Indigenous children in Canada were forcibly removed from their homes and sent into the Indian residential school system. These government-led schools were created to assimilate Indigenous children into colonial society and to be ashamed of their culture and beliefs. Most were exposed to frequent physical, sexual and emotional abuse. According to the First Nations Centre, residential school survivors are more likely to suffer mental health problems compared to those who did not attend.

Decades after the last residential school closed, the trauma of survivors can continue to negatively affect their offspring, explained Dr. Kim Matheson, a neuroscience professor at Carleton University who studies the social determinants of health in Indigenous populations.

“Even though the next generation didn’t actually experience the trauma, they show many of the same behaviours, emotions, and mental wellness that one would see in someone who has experienced a trauma,” she said.

This process is called intergenerational trauma, defined as the transmission of the experience of trauma in one generation to negatively affect the wellness of the next. According to the First Nations Information Governance Centre, 37.2 per cent of people who had at least one parent attend a residential school thought about committing suicide at some point in their life, compared to 25.7 per cent who did not have a parent attend.

Matheson said supporting the offspring of survivors by building stronger cultural support and identity is an important part of healing. Scientists are also investigating how an aspect of our biology called epigenetics plays a role in the passing of trauma through generations. Understanding how intergenerational trauma is transmitted at a genetic level has the potential to support the development of programs that could help people with intergenerational trauma overcome the past.

The role of epigenetics

Although there are many different processes by which intergenerational trauma can be transmitted, epigenetics is a prime candidate, explained Dr. Hymie Anisman, a professor in the department of neuroscience at Carleton University.

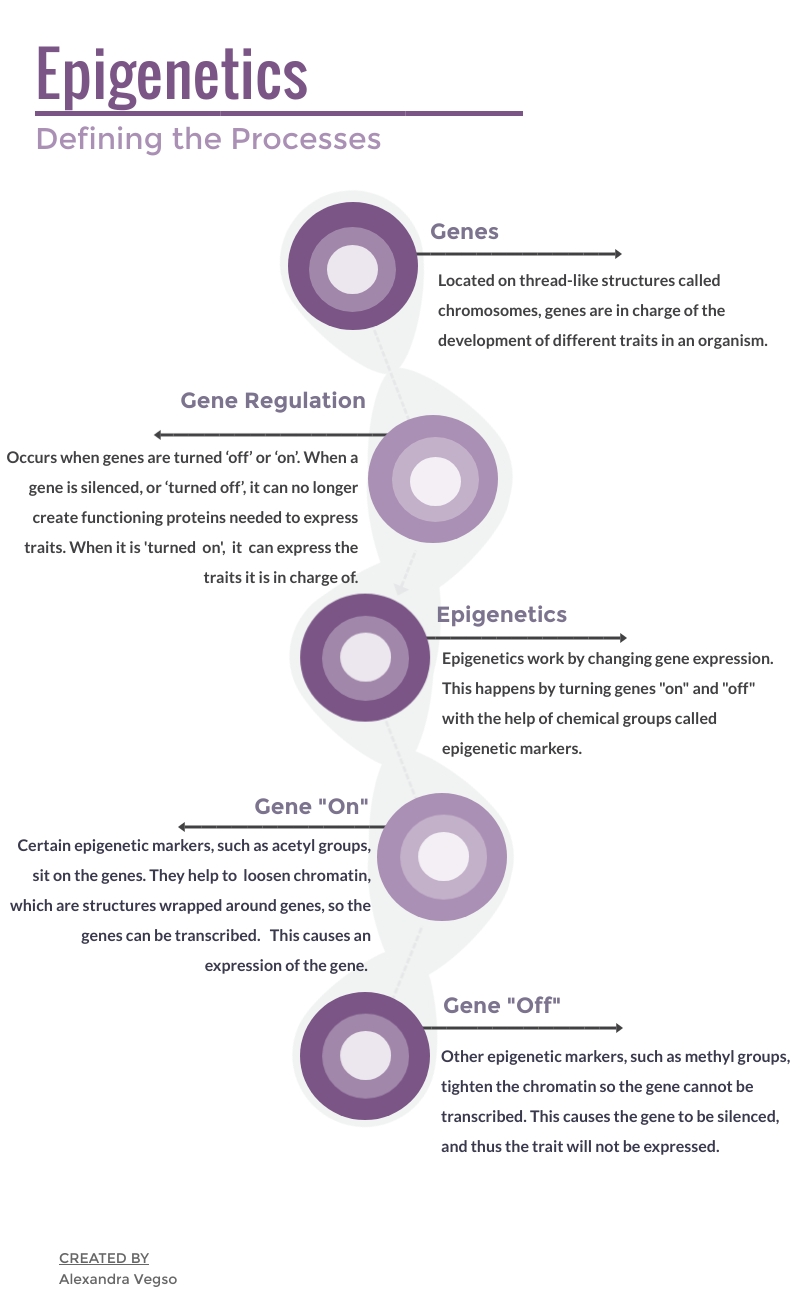

Epigenetics is a process in which environmental factors change the expression of a person’s genes. The genetic code itself is not altered. Rather, chemical modifications to the DNA sequence result in some genes being silenced or being expressed in greater abundance than before. These modifications result in fundamental biological changes within the individual.

“For example, there might be certain aspects of a gene that protects you from cancer,” said Anisman. “Now, if that certain aspect of your gene is [turned off], the cancer is free to spread.”

The same thing can be said for traumatic events, Anisman said. If genes that protect someone from stress-related illnesses – for example, depression or post-traumatic stress disorder – are silenced by epigenetics, that person could be at increased risk for these mental illnesses.

There have been many studies that suggest traumatic events can cause epigenetic changes. For example, in a 2009 study, researchers found epigenetic changes in the brains of children who suffered traumatic child abuse, which increased their risk of committing suicide.

As evidence began to mount that trauma led to epigenetic changes in an individual, researchers began to investigate whether these modifications might be passed from one generation to the next. In a 2018 review, researchers at the University of Northern British Columbia concluded that an important relationship exists between intergenerational trauma, traumatic events, and epigenetics for residential school survivors and their families. Identifying which environmental factors are specifically causing the epigenetic changes can be difficult, Anisman said. In the case of intergenerational trauma, a source of these changes may lie in the support, or lack thereof, of the surrounding community.

“If I have the right social support from the right people, those with whom I identify strongly, it can be a very powerful way of coping. So [I] won’t see the neurobiological changes that [I] might see otherwise.”

Anisman added that supportive interactions during upbringing are particularly important for reducing the transmission of trauma to children.

Dr. Hymie Anisman has completed extensive research on intergenerational trauma in indigenous communities. [Photo © Alexandra Vegso]

The importance of upbringing

Understanding why these epigenetic changes are occurring is an important step in alleviating the effects of intergenerational trauma, Anisman said. That’s because epigenetic changes can be reversed, as only about five per cent are permanent. One-way epigenetics could potentially be reversed is through positive social surroundings, Anisman added.

If a child does not grow up under good circumstances, they may have certain epigenetic changes, he suggested.

“But if I put him in a really great supportive environment with lots of friends and people taking care of him, those epigenetic changes can be undone.”

Anisman said many original survivors of residential schools raised their children with harmful behaviours they witnessed themselves in residential schools. He suspects that this parenting may have resulted in negative epigenetic changes in their offspring, a theory that has yet to be definitively proven in residential school survivors, although it has been seen in other cases of intergenerational trauma.

Residential schools taught some survivors how to be bad parents, said Anisman. “They emulated the people who looked after them and thought that abuse was normal.”

Addressing upbringing within the community

Dr. Cheryl Currie, an associate professor at the University of Lethbridge who studies Indigenous health, agrees positive upbringing could alleviate some symptoms of intergenerational trauma.

Currie has worked with Indigenous communities across Canada to address issues the communities deem important, for example, discipline within the household. The residential school system often taught children that it is better to punish rather than praise.

“I had an elder once tell me: ‘What residential schools did was it took the sweetness out of our families. You know, hugging your children is a sin, hugging your sister or brother is a sin.’ So, it really made people feel that even being close to someone is sinful.”

One of the programs she helps administer aims to foster a positive connection between parents and their children. The Strengthening Families Program usually runs for twelve weeks, and a typical session starts with facilitators talking to the children and parents in separate rooms about various topics, one of which is positive reinforcement.

“What residential schools taught is punishment, you punish behaviour. But positive reinforcement, looking for when your kids do something you like and then praising them for it, is much more effective than punishments,” said Currie.

At the end of the session, parents and children come together and complete exercises where they practice positive reinforcement together. Currie said these programs have helped families become closer to each other as well as their culture, which has tremendous effects on wellbeing.

A 2019 study conducted by Currie, which examined childhood racism and its impact on stress, found Indigenous adults who have experienced a significant amount of racism will undergo advanced wear and tear, called allostatic load. Allostatic load refers to dysfunction in the body as a result of prolonged stress, and it results in physiological problems, such as inflammation, high blood pressure, and an inability to shut down the body’s stress response.

However, Currie found that people who were practicing their culture intensely and had a positive identity related to their culture did not undergo as much allostatic load as a result of racism.

“So all those colonial characterizations of what Indigenous cultures are, they see through that,” Currie said. “They’re experiencing racism and it’s awful, but they’re more likely to feel like ‘I don’t deserve this’.”

The result of fostering favourable emotions towards one’s culture may be resilience, Currie added, leading to better protection against trauma.

Resilience of Indigenous peoples

While epigenetic and physiological changes caused by trauma can result in vulnerability to different illnesses, they might also create resilience. Anisman said when we study vulnerable populations we tend to focus only on the bad and ignore the good that may have come from their experiences.

Anisman explained that some epigenetics changes in our genes could be beneficial, for example by increasing protection to a disease instead of vulnerability to it.

Survivors of residential schools have also gained a great deal of resilience from their ability to cope with their shared trauma, said Matheson. Finding community and social belonging is key in recovering from trauma.

“You’ll hear elders talk about the friendships they had and how important they were. They may talk about the tricks they pulled on the staff,” she said.

Matheson explained their ability to laugh and find humour in their experiences is an incredibly important coping mechanism and renders resilience.

Anisman agrees. He said shared experiences bring people together and allow them to form special bonds that help them cope with the traumatic events. Perhaps, this also plays out at a biological level too.

“Resilience is not just a person, resilience is a whole community,” said Anisman. “Everybody working together, everybody sharing. It strengthens the groups as a whole and therefore strengthens the individual.”