Salmon farming of the future

With two Federal parties pledging to convert all of BC’s salmon farms to close-containment facilities by 2025, industry experts have raised a number of concerns

By Lauren Hicks and Melanie Ritchot

Venture Point fish farm, owned by Norwegian company Cermaq, is approximately 150 km North-West of Vancouver. Lights illuminate the water to increase “daylight” feeding hours. This practice also attracts wild species like herring and salmon to the farms. [Photo © Tavish Campbell]

Feeding fish, monitoring water quality, removing waste, and checking health are all in a day for workers in a Canadian salmon hatchery. Kenny Leslie, a supervisor at Big Tree Creek Hatchery on Vancouver Island is one of them. He has been working in hatcheries for nearly five years since he moved to British Columbia from Scotland.

A fish farm’s production cycle begins when workers like Leslie introduce young salmon called “fry” to a diet of fish feed. Weighing 1.5 grams at first – about the weight of a paperclip – workers watch the fry grow for at least nine months before transporting them – 30,000 at a time – by truck, and then by boat, to open ocean pens where they’ll reach maturity.

“They’re amazing creatures to watch,” said Leslie. “In any given week they’ll change so much, and it’s impressive how quickly they develop in that life stage.”

Knowing he helps produce so many portions of fish – a relatively healthy form of animal protein compared to red meat – for consumers is one of the highlights of working on a fish farm, Leslie said.

Yet not everyone is thrilled with Canada’s current open-pen salmon aquaculture system. Some advocacy groups and certain Federal parties are concerned about the industry’s negative impacts on the environment and coastal ecosystems. During the 2019 Federal election, Justin Trudeau’s Liberals and Elizabeth May’s Greens vowed to take action.

The Liberals promised British Columbia’s farmed salmon would be moved from open net pen farms to in-ocean closed containment systems by 2025, while the Greens want to move all salmon farms out of the sea and onto land in the same timeframe. Critics argue that both parties’ plans are unfeasible, that they would require immense resources and that the technology is not yet ready to accommodate the changes promised. However with rapidly rising ocean temperatures, climate change may force the farms on land before the debate is settled.

Aquaculture, or fish farming, is probably the fastest-growing animal food-product industries in the world, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Over 50 per cent of fish on the market across the world comes from aquaculture and this demand is increasing by up to 10 per cent each year, according to Tim Kennedy, President of the Canadian Aquaculture Industry Alliance.

Mowi, the Norwegian company that runs the hatchery where Leslie works on Vancouver Island, produces 45,000 tonnes of Atlantic Salmon per year in British Columbia alone. Between all salmon farms in the world, 2.5 million tonnes of salmon is produced per year, according to the International Salmon Farmers Association.

Canada is currently the fourth largest Atlantic Salmon producer in the world, after Norway, Chile and the United Kingdom. But Canada’s 40-year-old aquaculture industry has the potential to expand considerably.

With the longest coastline in the world, Canada only uses about 1 per cent of our marine capacity for fish farms, according to Tim Kennedy, President of the Canadian Aquaculture Industry Alliance.

Marine-based salmon farming

Aside from a couple of pilot projects and small-scale on-land facilities, Canada primarily farms salmon in marine pens. The pens, consisting of little more than a net anchored to mooring equipment, places the farmed salmon in direct contact to wild salmon populations and coastal ecosystems. In the past, this system of direct contact to natural ecosystems has drawn criticism.

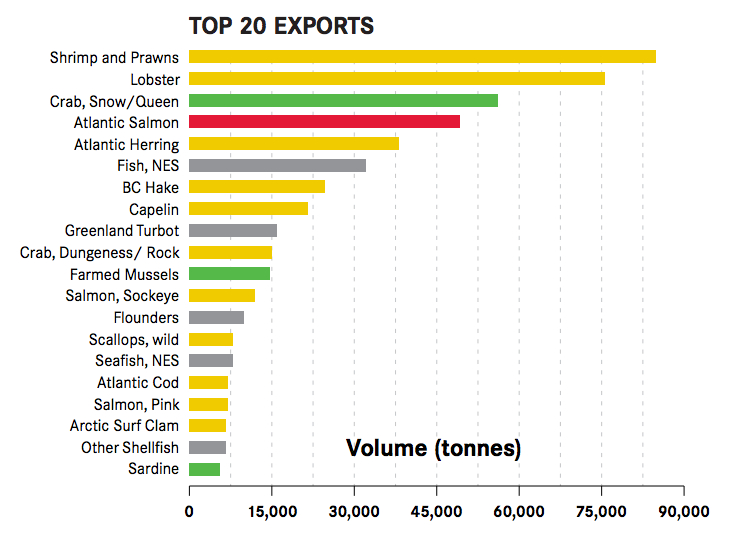

Top Canadian fish exports in 2017 by volume. Colours are based on Sea Food Watch advisories at the time. From: Statistics Canada.

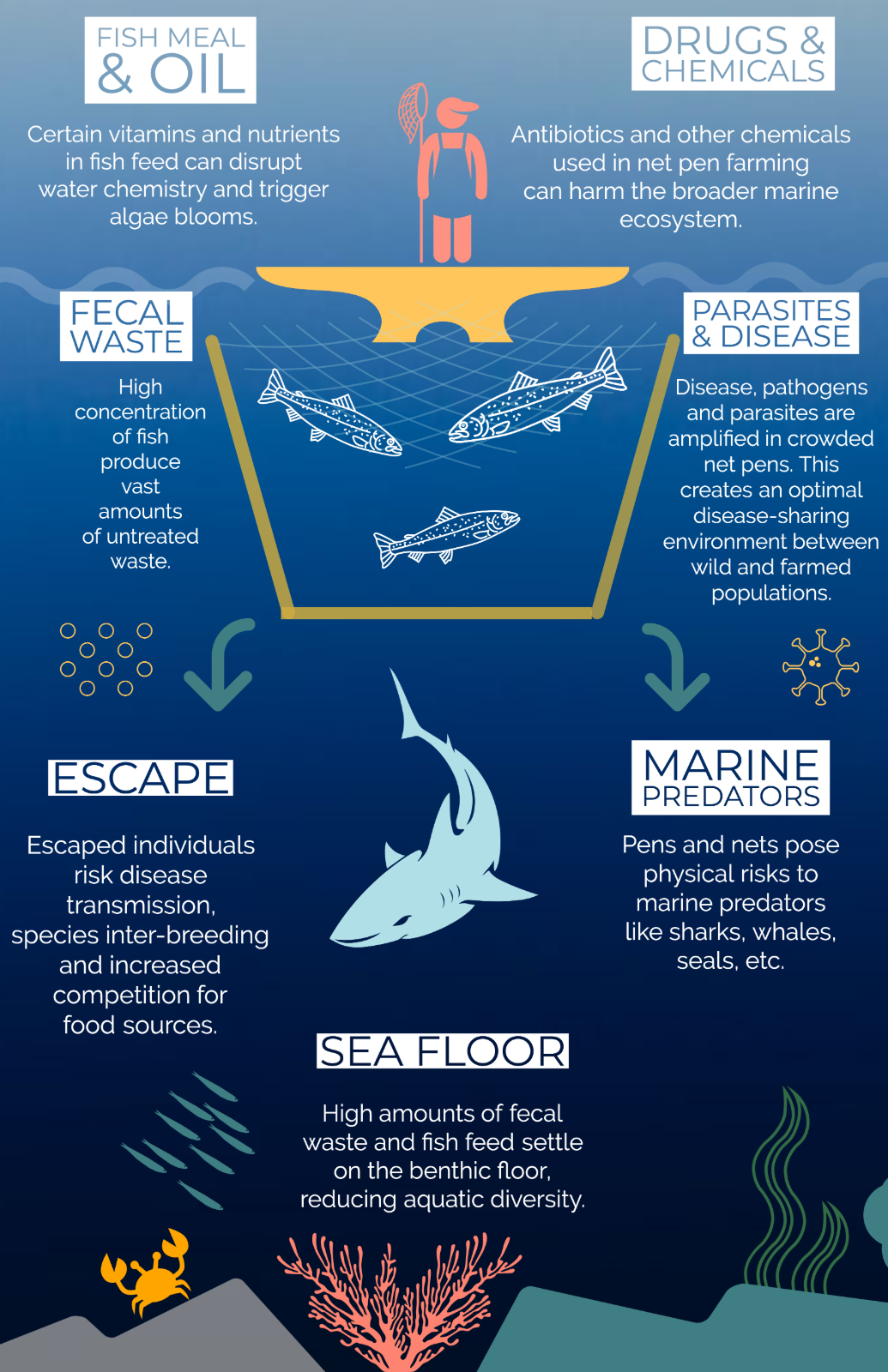

One of the issues is fish waste. Many advocacy groups, like Ecology Action Centre, worry that large amounts of fecal waste could contaminate the water – spreading disease, smothering the sea floor, and ultimately reducing aquatic diversity.

Another issue with open-pen sites are mass escapes that happen when netting or mooring equipment breaks. This might allow farmed Atlantic Salmon to breed with wild salmon on the Atlantic coast, reducing genetic diversity in the wild population.

Wild salmon smolt make their way up the B.C. coast, passing a patch of ocean kelp. [Photo © Tavish Campbell]

Disease epidemics are also a growing problem, according to Dr. Brian Dixon, a fish immunologist at Waterloo University.

“[Researchers] are working on vaccines but the problem is that vaccines do not work well in fish,” explained Dixon.

According to Dixon, the high density and proximity of farmed fish often leads to infectious disease spreading quickly. Fish tend to be treated with antibiotics when disease spreads. According to Dixon, Canada’s west coast dumped 150 tonnes of antibiotic into the ocean last year.

“One veterinarian I know says he remembers writing a single prescription for 1,500 kilograms of antibiotic,” said Dixon.

Aquaculture farm worker Leslie, who has a degree in environmental sustainability, said he thinks environmental concerns are overblown and this electoral promise was made to get votes from those who are against salmon farming.

Various political parties and environmental groups have voiced concerns surrounding a number of issues associated with open-pen fish farms. [Graphic © Lauren Hicks]

“They’ve never been on a farm, they’ve never seen it, they’ve just heard that aquaculture is bad, he said. “There’s absolutely no way I could do this job if I thought it was degrading to the environment in any way.”

Industry lobbyist Kennedy argues that even though aquafarms can have multiple, detrimental effects on the coastal environment, their overall environmental impact is much less than other land-based protein producing industries.

Farmed salmon is the most efficient meat protein in the world based on carbon emissions and space efficiency compared to beef, chicken and other meats, Kennedy said.

That’s because open-pen farming utilizes natural energy from water currents, similar to how windmills use wind power and how solar panels engage energy from the sun, he said.

But regardless of whether marine-based salmon farms require relatively little energy, climate change may make these coastal farms unfeasible Dixon explained.

Atlantic Canada’s ocean temperatures are set to increase by two to four degrees in the next 30 years.

“On the East coast, some inlets are peaking at nearly 17°C in the summer months. If you start getting up to 19 or 20°C , that is lethal for Atlantic salmon,” Dixon said.

This means, according to Dixon, that marine farms may need to move north or onto land in enclosed pens. By this logic, the Liberal and Green proposals may be a necessity.

Yet industry professionals argue that the technology is not ready. They don’t believe such a big move is feasible within five years, the timeline of the party platforms.

Closed-pen and land-based salmon farming

Closed-pen and land-based systems are less common farming methods, designed to function as closed water systems with no direct contact with wild populations or natural ocean ecosystems.

Atlantic Sapphire, near Miami, Florida, is considered the leading land-based salmon farming facility in the world, according to Kennedy.

He said their secret is the area’s unique geology.

The company avoids high expenses by pumping massive amounts of water from deep underwater deposits called aquifers.

They also have permits to dispose of waste from the tanks deep underground below the water table, which reduces the cost of filtering and treating the water.

According to Kennedy it is unclear whether this could work in Canada because the country’s geology is so different than Florida’s.

Some small on-land systems have been piloted on both coasts of Canada of Canada and in some First Nations communities with federal funding. But many scientists, like Dixon, do not think the technology is ready to handle the sheer size of Canada’s aquaculture industry.

Jonathan Grant, a professor in the Oceanography Department at Dalhousie University, agrees that Canada’s industry is not ready to make the switch.

“If you did the analytics and saw the number of jobs lost, the disruption to the industry, and…the capital costs of building those factories, it is pretty significant,” said Grant. He added, “It is a total illusion that the problems go away because [fish farms are] on land.”

Kennedy thinks we’re more likely to see closed containment pilot projects in the ocean than on land, but even those face challenges.

Problems Grant anticipates with closed-pen systems include tremendous energy and water requirements, reduced fish welfare, rampant disease outbreaks and potential power failures.

Indigenous peoples have the most at stake in decisions about the development of the salmon aquaculture industry, as virtually all salmon farming operations in British Columbia fall within their traditional territories, according to research published by Marine Policy.

If large-scale land-based salmon farming was feasible in Canada, Kennedy said this would have immense impacts on Indigenous nations, since the industry employs many Indigenous persons and most farms are located on their land.

Caption: Marine-based and on-land salmon farms look completely different, as seen here by comparing marine-based pens in Okisollo, BC and land-based farm Atlantic Sapphire in Florida.

In British Columbia, 20 per cent of all workers in the aquaculture sector are Indigenous, which is a significant amount, considering only 5.9% of the province’s overall population is Indigenous, according to Statistics Canada.

The majority of farmed Salmon production in British Columbia is made possible by agreements with First Nations. [Graphic © Melanie Ritchot]

What’s Next

Instead of relocating fish farms to closed marine systems or on land, Dixon advocates for pursuing advancements in mooring technology, disease control practices, and optimal site selection procedures as a way to address environmental concerns about aquaculture.

“I think the problem is that we need aquaculture. The industry is trying to be an environmentally conscious as they can, they are experimenting with new diets, new vaccines, new technologies. It is just going to take time,” said Dixon.

With many jobs and competing interests at stake, it is unclear whether the Liberal government will implement their campaign promise, and force Canada’s aquaculture industry to radically change–and whether, in a minority government, they will have the political backing to do so. Regardless of the direction politicians, policy makers and the industry try to take fish farming in the future, climate change may have the final say.