Shaming the vagina: The psychology and pseudoscience of “health and freshness” marketing

By Jensen Edwards and Olivia Robinson

In the feminine care aisle of many pharmacies and grocery stores, vaginal wipes often presented beside menstrual products like pads and tampons, conveying on the packaging that special hygiene practices are required during menstruation. [Photo © Olivia Robinson]

Chicken scratch in black permanent marker caught Courtney Howard’s eye when she reached for a tampon at the University of British Columbia’s women’s centre. “Get a Keeper!” was scrawled across the box. It was an anonymous plea to the medical school student and other women to eschew disposable products in favour of menstrual cups.

“I tried one first when travelling,” said Dr. Howard, now an ER doctor in Yellowknife. In her mind it was her only option: she was worried that tampons wouldn’t be readily available in the country she was visiting and she didn’t want handfuls of the menstrual product tumble out whenever she opened her backpack. The silicone solution worked without a hitch. Menstrual cups are inserted into the vagina – similar to a tampon – creating a vacuum seal that traps menstrual blood. A couple of times a day, aficionados wash the blood out of the cup and then reinsert into the vagina. Dr. Howard was unfamiliar with them before she did her research, having grown up bombarded with white-pants ads from major manufacturers that have long dominated the menstrual product market. She went on to do the world’s first randomized controlled trial, comparing tampons to menstrual cups in women who had previously used tampons. Ninety-one per cent of participants said they would continue to use the cup, after the trial.

Since the explosion of “femcare” products in the 1920s, personal care companies have framed discussions about menstrual products with shame and euphemism. With little oversight and research, unregulated vaginal hygiene cleansers, deodorants and wipes populated shelves of drug stores alongside tampons and pads. “Clean and fresh” has become their mantra, preying on people’s fears that their vaginas are breeding grounds for “dirty” bacteria – fuelling a $2-billion industry in North America. Pseudoscience remedies are peddled by lifestyle brands and independent Etsy sellers alike. In all the noise, legitimate vaginal healthcare needs are often pushed aside – something that some doctors and science-minded menstrual activists are hoping will change.

Selling shame

Most packaging for vaginal hygiene products like gels, sprays, deodorants, wipes, douches are littered with words like “fresh” and “clean” – language that suggests the vagina should be odourless, hairless and unobtrusive. It’s a narrative that has been peddled since at least the 1930s, when fragrances were added to menstrual pads to mask natural odours. But that doesn’t mean that the additives are necessarily innocuous.

Kieran O’Doherty, a psychology professor at the University of Guelph, points out that the freshness claims can be at odds with vaginal health.

According to a study published in 2011, using feminine hygiene products can disrupt the healthy vaginal microbiome, sometimes making the vagina more acidic than its normal pH of 4.5.

The vaginal microbiome consists of naturally occurring bacteria, viruses and fungi that, when in proper balance, help maintain health and help protect against pathogens like sexually transmitted infections. This community of symbiotic bacteria can be affected by things like antibiotics, sexual activity and vaginal hygiene practices.

In a 2018 paper in BMC Women’s Health, O’Doherty and colleagues were among the first to look at women’s vaginal hygiene behaviours through a psychological lens. They studied commercially available and naturopathic products and their associations with the health of vaginal microbiome.

O’Doherty found that “a least a quarter” of Canadian women have used cleansers, deodorants, wipes and other such products at some point in their lives, albeit not regularly. He concluded that the women surveyed in his study were self-conscious about having the “perfect genitalia” and unrealistic ideals of “hairless, odourless vaginas.”

Many of the participants in his study described feelings of shame about vaginal odour. “The bigger picture is that these products seem to be targeted towards certain insecurities and these insecurities are fanned by the marketing and the existence of those products,” O’Doherty said. “To me, that’s more where the problem is.”

The Newer Knowledge of Feminine Hygiene was a small booklet advertised in Canadian newspapers in the 1920s. Women could send away to the company to gain knowledge about “feminine hygiene” and “personal daintiness” and how the vagina was plagued with unbecoming bacteria. The booklet is ultimately an advertisement for Zonite, a company that sold douching products, ointments and a “marvel whirling spray.”

What is the vaginal microbiome?

Lactobacilli – composing of Lactobacillus crispatus, Lactobacillus gasseri and Lactobacillus jensenii – are some of the most common bacteria found in healthy vaginal environments. Lactobacilli converts lactose and sugars into lactic acid, which helps to stave off infections. [Source : https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3780402/]

The “cursed” history of menstrual products

The so-called menstrual “curse” was long hidden under layers of petticoats and rubber aprons, which concealed the “dirty” reality of femininity under a lily-white veil, wrote feminist scholar Elizabeth Kissling of Eastern Washington University in her 2006 book, Capitalizing on the Curse. Even “as mobility increased [through access to tampons and pads],” Kissling writes, “so did the demands of ‘freshness’ required of women.”

In the 19th century, hand-knitted cotton pads were pinned into undergarments or buttoned onto belts to capture menstrual flow. Catamenial sacks, for instance, were among the first non-absorbent devices to be used to contain menstrual flow. Worn externally and supported by suspenders, the rubber cups were “of sufficient size for the purpose [to contain menstrual blood],” according to one patent from 1896.

Less unwieldy than its 1800s predecessor, the first internal menstrual cup was made out of latex and patented in the 1930s. The cups were so convenient for transport and capture of fluids that Ernest Hemingway was known to sip gin from one on trans-ocean flights. Despite celebrity endorsements, the cup failed to fly with consumers until the 1980s, partly because early would-be users may not have felt uncomfortable washing them out.

Despite decades of commercial availability, menstrual cups, and menstrual products in general, have received little academic attention. When studies are published, wrote Kissling, they are often perceived as “exciting or inappropriately … taboo breaking.”

One 1970s Canadian parliamentarian bemoaned the fact that Statistics Canada was studying the number of sanitary pads used per household, calling it a “strange priority” for the government. He argued that “[the government] conducts studies on what people do in their bathrooms, but it cannot raise money for the widows of veterans,” widows who may have also been spending their late husbands’ pensions on sanitary pads.

Social media: A Wild West for pseudoscience

Social media influencers and entrepreneurs have capitalized on fear and shame to push pseudoscientific products. Such fear-mongering, like unsubstantiated claims of known carcinogens contaminating tampons, has pushed prominent companies like Tampax to issue a disclaimer on its website that its products have “never contained asbestos.”

This fear of the unknown has spurred a crop of “organic” menstrual products, tampons included. But when it comes to organic menstrual products versus regular menstrual products, there is a lack of research and evidence to point to any clear health benefits from the more eco-friendly option.

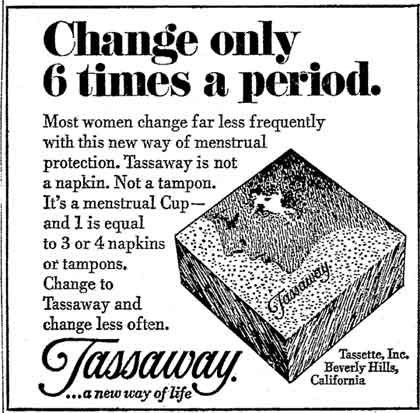

The Tassaway was the disposable replacement for the unpopular Tasette, a reusable rubber menstrual cup introduced in the 1960s. It solved two problems for its manufacturer: it would let women avoid having to wash out their cup and unlike its reusable predecessor, it would make customers come back sooner to buy more.

[Image courtesy of Museum of Menstruation and Women’s Health]

“If you’re somebody who avoids pesticides and other parts of your life, you may personally have a reduction in stress,” she said. “So you can count that as a mental health benefit, but I don’t think we know enough [to make conclusions about vaginal health benefits].”

Rachel Ettinger, founder of Here for Her, is less concerned about the differentiation between these products. She’s focused on people getting better access to menstrual products in the first place. Her organization aims to reduce the stigma around women’s health and regularly coordinates donations of menstrual products to those in need.

“All I know is that the organic pads and tampons are so expensive, even for me – and I have a full-time job. Even I can’t afford to buy an $8 or $10-pack of organic pads,” she said.

In addition to the organic market, consumers are looking to alternative vaginal products for esthetic rejuvenation – harkening back to Zonite’s merchandise from 1928 that promised “thorough germicidal action” to kill “germs” that caused “distress during menstruation.”

Products created under the guise of a vaginal hygiene label are finding new audiences in online marketplaces like Etsy. Amanda Laird, host of the period-positive podcast “Heavy Flow,” cautions against the “gimmicky products that really don’t have a function” – like vaginal exfoliators and douches – saying that these products could potentially do more harm than good. They prey, she said, on the same fear of uncleanliness that their predecessors have been doing for almost a century.

“The name ‘feminine hygiene products’ makes it sound like we are dirty,” said Ettinger.

“I think that femcare or feminine hygiene industry is marketing towards somebody who is trying to erase their bodily functions,” said Laird.

“Yes, you can get a yeast infection or a bacterial vaginal infection and that’s definitely going to make you feel less-than-fresh, but on a day-to-day basis, our vagina is a self-cleaning organ. We don’t need to be douching.”

O’Doherty’s goal – much like Dr. Howard’s – is that there should be more biomedical research done in in the vaginal health market to clean up misconceptions about vaginal health and hygiene. They hope more studies will pinpoint whether using vaginal hygiene products or menstrual products can cause a vaginal infection or irritation.

Where insecurities today flow from online trends and social media esthetics, Dr. Howard believes that cutting out unnecessary and unhealthy expectations of vaginal hygiene can help mitigate any shame.

“We probably can’t solve Instagram’s impact on your self-esteem,” she said, “but we definitely can prevent Canadian girls and young women from hitting menarche and not having a really good sensible set of [menstrual product] options available.”

In “Women’s genital body work: Health, hygiene and beauty practices in the production of idealized female genitalia,” Kieran O’Doherty reported that female respondents in his survey felt the need to carry deodorant sprays that could be used in public spaces, like at school. [Photo © Olivia Robinson]

Scare of toxic shock

in the 1980s

Advancements in the materials used in menstrual products led to a public health scare in 1980, when 814 women became ill because of Toxic Shock Syndrome, TSS, and 38 died from the disease.

The blood infection occurs when a proliferation of bacteria, Staphylococcus aureus, is fostered by a tampon left in place for too long, thus allowing the bacteria to grow. High-absorbency tampons made of synthetic fibres allowed users to leave tampons in longer, leading many to experience TSS. To exacerbate the problem, the synthetic fibres were more conducive to rapid bacterial growth than cotton predecessors.

After the TSS crisis, the U.S. Federal Drug Administration began requiring tampon producers to include a universal absorbency rating on all of their products. The same regulation and scale was reproduced in Canada. Warnings on how to prevent TSS must also be including on packaging.

Meanwhile, brands pulled their high-absorbency tampons in favour of simpler materials that were less likely to result in TSS with their absorbency rates.

Risks of TSS were not caught in the development stage of the rayon tampons. Such is the case with many vaginal health and hygiene products: there is little clinical and regulatory oversight to evaluate the risks to the vaginal microbiome and user’s overall health.