Threat to sustainability: How fishing endangered species is impacting Canada's ocean economy

By Lia Pizarro

Capelin are a small fish with a big responsibility.

Traditionally used as fertilizer or bait, capelin is a small, forage species that attracts numerous predators such as fish species and marine birds. They live in the northwest Atlantic in vast areas that span throughout the Labrador coast and St. Lawrence Estuary.

Prior to the 1970s, capelin fisheries in the east were non-existent.

Today, capelin roe (or spawn) is sold primarily to the Japanese market – where the species fishery is skyrocketing.

Yet the importance of this species has prompted the Department of Fisheries and Oceans to increase efforts in protecting this popular resource.

So why is this a concern today?

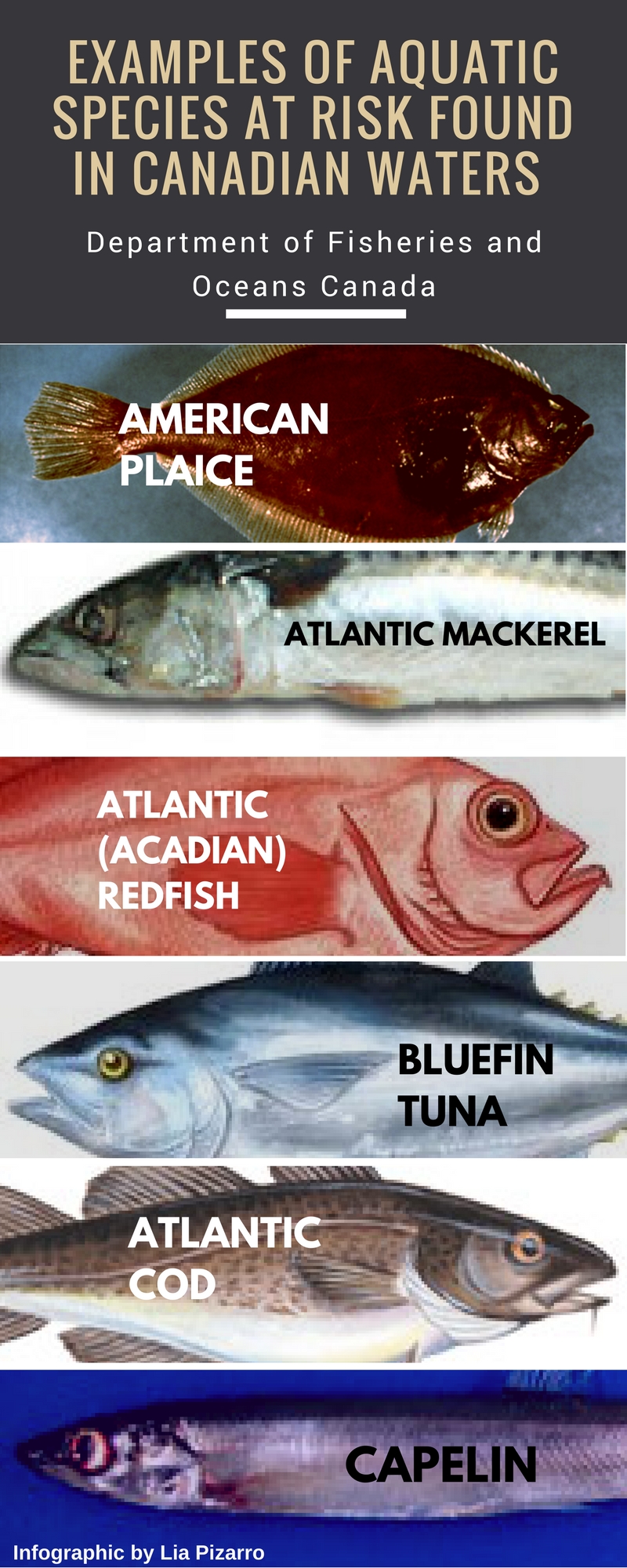

Aquatic species declining and the need for greater marine conservation are two major aspects that have threatened the growth of sustainability, especially in coastal communities along the Atlantic.

In April of this year, the DFO spent more money and time understanding why capelin stocks did not recover, putting almost $2.4 million on surveys to assess the stock.

Despite improvements to the management of fisheries over the past few years, Canadians remain unaware of the looming fate that our ocean economy could face by continuing to fish endangered and threatened aquatic species.

Marine conservation coordinator, Susanna Fuller, says Canadians should be more vocal and demand greater ocean protection.

“I don’t think Canadians realize how many fish populations are endangered or threatened and that we continue to fish them,” said Fuller, “They don’t know that we are fishing at the bottom of our food web and that when those are done – there isn’t much left.”

Overfishing species at the bottom of the aquatic food chain has serious implications for the entire marine kingdom.

“We’ve seen huge declines in herring and mackerel in the last five years, which are the base of the aquatic food chain, and they aren’t rebounding very quickly like they usually do,” said Fuller.

In terms of losing the population of commercial fish, there are a few species, like the American plaice, that are showing signs of decline.

For many years, Canadian fisheries have also commercially fished species that are considered to have low stock levels, such as tuna and cod.

“When those are done – there isn’t much left.” – Susanna Fuller

Cod set out to dry after being cleaned and salted in Fogo Island, 2017. Atlantic cod are one of many species considered to be threatened or endangered by the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada. [Photo © Lia Pizarro]

“We’ve done more ocean protection in the past two years than we have in the last 150”

The Department of Fisheries and Oceans

According to a representative from the DFO, the stock status of intended targets of a fishery, whether in a commercial, recreation or subsistence fisheries, are regularly assessed.

The DFO recognizes that overfishing, among other concerns, is a global problem with many serious social, economic and environmental implications.

When a stock status falls below the point at which serious harm is occurring to the stock, known as being in “the critical zone”, management decisions are made which promote stock growth. A rebuilding plan is put into place with the aim of growing the stock out of the critical zone within a reasonable time frame.

The Atlantic Mackerel for example, has a stock status that is currently in the critical zone and as a result, management decisions have been made with the aim of improving the health of the stock. This includes limiting the Total Allowable Catch (TAC), as well as freezing the issuance of new commercial mackerel licenses.

The concern that Fuller presents is that by enlisting certain species, many fisheries are at risk of closure. Socio-economic issues often trump the decision to list a species as endangered.

Map of Aquatic Species at risk (by the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada): http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/species-especes/fpp-ppp/index-eng.htm

Impact in the East and lessons from the cod collapse

The decline in aquatic species has been taking a toll on coastal towns along the Atlantic for many years, where rural areas depend on these industries for their economy.

Almost two decades ago, Canada experienced the largest fish collapse in its history – the decline of the northern cod population.

The historic cod fisheries in the Newfoundland and Labrador region attracted local and international fishers for centuries – and employed thousands of Canadians along the Atlantic coast. Since the incident, the government was forced to impose a moratorium and shut down the industry as a result of the depleted stock.

Since then, the devastated cod population has shown very slow signs of rebuilding.

However, twenty-five years ago Canada did not have nearly as big a lobster, shrimp or crab fishery as it does today. Prior to the country’s infamous cod fishery collapse of the early 90s, cod used to feed on juvenile crab and lobster – species considered to form the base of marine food chains in a large part of the world’s oceans. When the cod population declined, there was a boom of these crustacean species and fisheries.

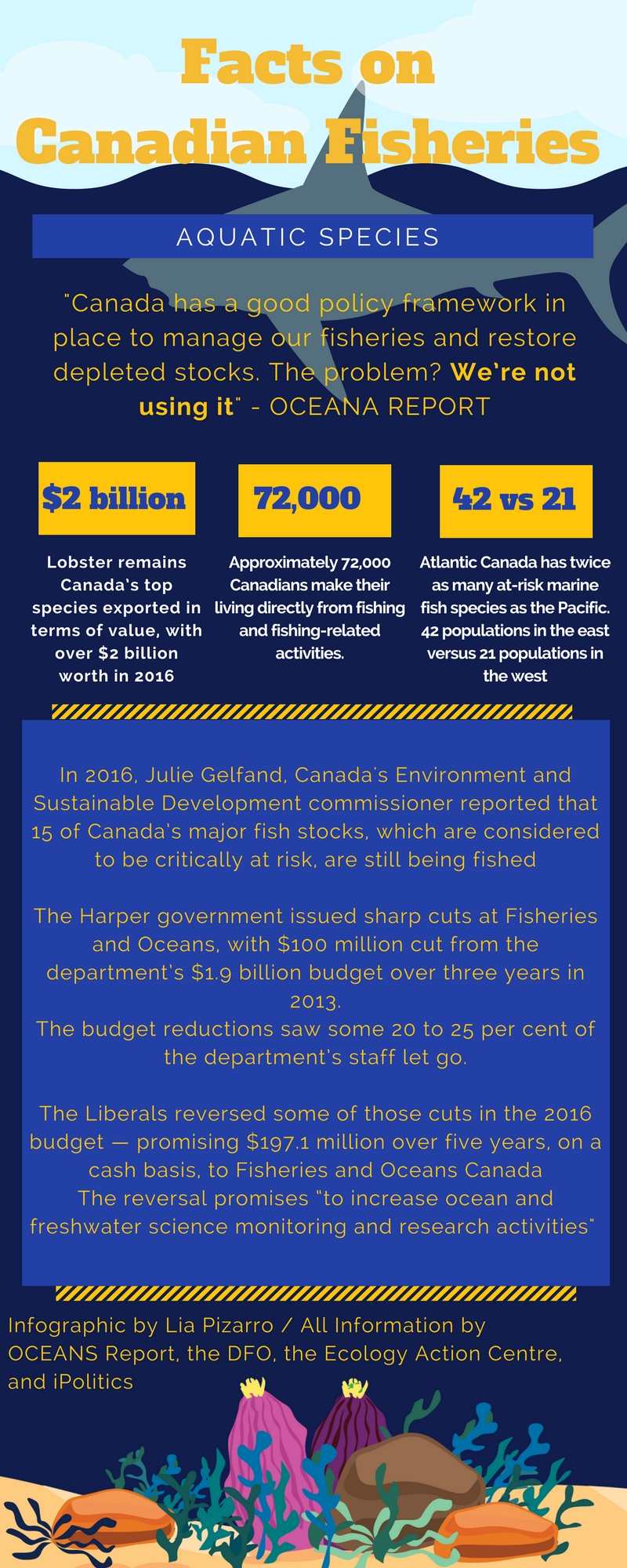

Today, we’ve shifted to lobster, shrimp, crab and shellfish fisheries, which are very valuable. Financially, we are better off fishing these species, especially as lobster remains Canada’s top species exported in terms of value, with over $2 billion worth in 2016. Canada was also the world’s eighth largest fish and seafood exporter in 2015, with exports to more than 130 countries – valued at over $6.0 billion.

“Lobster in Nova Scotia, in Atlantic Canada, is a billion-dollar industry. We don’t have any other billion dollar industries that employ thousands of people and are very important for rural areas. And if lobster did decline, who would it impact?” – Susanna Fuller

Since the time of the cod fishery collapse, there have been significant changes to fisheries management in Canada with a focus on the sustainability of our valuable marine resources and preventing any future fisheries collapse.

What is total allowable catch?

“The total allowable catch (TAC) is a catch limit set for a particular fishery, generally for a year or a fishing season. TACs are usually expressed in tonnes of live-weight equivalent, but are sometimes set in terms of numbers of fish.”

– The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

Photo on Heritage Newfoundland and Labrador of fisherman surrounded by cod on the Grand Banks, 1949. [Photo courtesy of Library and Archives Canada/National Film Board of Canada]

Local fisher holds salted cod in traditional cod shack on Fogo Island, 2017. [Photo © Lia Pizarro]

Environmental role

Patrick McGuinness, President of Fisheries Council of Canada, said that the council has been working closely with the DFO, collaboratively coming up with solutions whereby species at risk are protected.

According to McGuinness, United Nations reports have confirmed and stressed the significance of climate change and other environmental impacts on fisheries around the world.

“It’s not just harvesting and fishing that has an impact on the species. What we’re finding more and more is that it’s environmental issues.”

– Patrick McGuinness

The UN Sustainable Development Agenda reported that 31.4 per cent of the commercial wild fish stock were overfished back in 2013. Furthermore, climate change has been reported as a significant threat that have displaced fish species, reduced fish production for export and hurt the economies of coastal communities.

McGuinness said that a major cause of species decline in a specific area could be attributed to changes in access to food and water temperature. For instance, fish moving up north often do so to maintain a certain temperature that will help them survive from warmer, southern temperatures.

He also believes this was a similar occurrence during the cod fishery collapse.

“Mother nature had a big impact on the northern cod. Yes, there was probably overfishing but at the same time, the oceans were going through significant changes in terms of changes in the water temperature. It was becoming much colder,” said McGuinness.

Reports from the Northeast Fisheries Science Centre in the United States shared a similar assertion, stating that rapid warming waters are making the Gulf of Maine less hospitable for species like the cod, reducing the capacity of cod populations to rebound.

Future of fisheries through political involvement

While the DFO states that they have taken greater responsibility to properly manage fisheries and oceans, as well as working to ensure that fish stocks remain at healthy levels, Fuller says that Canada has not implemented many of the lessons learned from the cod collapse, and part of that reason is because of political will.

“Canada wants to be an ocean leader but we have a lot of catching up to do,” Fuller said. “We need more economic balance but more ocean protection – so there’s tension between those two things.”

Fuller believes that commercial fisheries need to be more engaged with DFO managers – people who are heavily involved with making big decisions towards improving the industry by restocking and repopulating fish species.

She also sees greater political involvement with the Liberal government, who are paying more attention to ocean protection and marine conservation.

“I think we’ve seen with this government that when they adopt a mandate around the oceans, they are working hard to fulfill it,” Fuller said.

However, short term economics versus long term population monitoring and rebuilding has always been a problem in fisheries decision making. This makes it difficult to manage dealing with major issues, such as species decline, right away.

These issues are not only overwhelming in scope and impact, but they also make smaller victories for fisheries in Canada not feel like they are enough to make a real difference.

“The time it takes to make real policy changes and implement them happens on a decadal scale, and often that does not feel fast enough,” Fuller said.