Starving for likes

How Instagram is affecting the modern day eating disorder

By Meg Sutton and Sarah Tsounis

When scrolling through your Instagram feed, you might see dogs so cute you could cry, your parents posting a selfie, evidence of your friends on their most recent night out, mouth-watering bowls of food — and bodies you wish were yours.

“It’s funny. I’ll take out my phone and start scrolling, then close it. And for some reason, unconsciously, I’ll pull it out and scroll again within the next minute,” she said. “It’s like I’m addicted to Instagram,” described M.T., a Carleton University student in her early twenties who enjoys reading Harry Potter books and drinking strawberry slushies. She agreed to talk on a condition of anonymity.

M.T. is one of a million Canadians who have struggled with an eating disorder — a mental illness which claims up to 1,500 lives across the country each year — as reported by the National Eating Disorder Information Centre (NEDIC). For M.T., it’s anorexia nervosa, and she’s not alone in feeling that seeing “thinspiration” or “fitspiration” on Instagram has an impact on her well-being.

For centuries, men and women have been pressured by society for their bodies to look a certain way — ideals which are constantly changing.

Critics have argued Instagram posts promote these ideals, that they are “pro-anorexia” content, and that they encourage the development of body image issues and eating disorders as individuals attempt to meet extreme appearance goals.

The power of these images, according to experts at the NEDIC, lies also in the fact they facilitate online communities dedicated to promoting and reinforcing harmful or dangerous behaviour relating to one’s view of themselves.

According to the National Eating Disorder Information Centre, anorexia nervosa is a life-threatening mental illness typically characterized by the following characteristics:

- Persistent behaviours, like restricting food and obessively exercising, to obtain a low body weight

- A fear of gaining weight or being ‘fat’

- Body image disturbances, such as overestimating and negatively evaluating body weight and shape

The National Eating Disorder Information Centre says Bulimia nervosa is a life-threatening mental illness characterized by a reccurent restricting, bingeing, and purging cycle. Individuals may go to extreme lengths to hide these behaviours.

Binge eating is consuming an unusually large amount of food in a short period of time.

Purging, which is meant to prevent weight gain after bingeing, can involve excessive exercise, self-induced vomiting and misuse of laxatives.

Self-objectification occurs when individuals treat themselves as objects to be viewed and evaluated based upon appearance. Studies have shown that men report lower self-objectification than do women, but young male adults are becoming progressively more worried about their physical aspect. In line with findings about women, men’s self-objectification is correlated with lower self-esteem, negative mood, worse perceived health and disordered eating.

There are currently more than 49 million posts, according to Instagram, with the hashtag #fitspo — the shortened version of “fitspiration.”

The word is a blend that combines “fitness” and “inspiration.”

The intent behind fitspiration is to motivate people to exercise, eat well, and take care of their bodies.

In the context of this article, “thinspiration” is used as a hashtag on Instagram. It typically references something or someone that serves as motivation for another seeking to maintain a very low body weight. The Oxford Dictionary connects it directly to content on social media related to anorexia nervosa behaviours.

“It’s funny. I’ll take out my phone and start scrolling, then close it. And for some reason, unconsciously, I’ll pull it out and scroll again within the next minute . . It’s like I’m addicted to Instagram”

As multiple research studies suggest Instagram is potentially detrimental for people who have or are at risk for an eating disorder, the social media company has taken action. In 2012, Instagram banned hashtags like #thinspo in its search engine, but just this year in 2019, after facing calls to strengthen its anorexia ban, users are now faced with a content warning when interacting with graphic body images. It’s a first step on a complicated path to supporting people with eating disorders on social media.

According to the NEDIC, Anorexia is a mental illness characterized by persistent behaviours involving weight maintenance, fear of weight gain, and an obscured sense of self. The causes, however, are not well-understood by medical experts.

“An array of biological, social, genetic, and psychological factors play a role in increasing the risk of its onset,” the NEDIC states on its website.

Danielle Kinsey, a Carleton University professor studying the history of the body, said anorexia has existed since the 12th or 13th century. Saint Catherine of Siena, one of the most notable eating disorder examples from that era, denied herself food as part of a spiritual cleanse.

“Eating was seen as a form of indulgence, or a sin, so clergy members would restrict their intake in order to be considered purer within the church,” Kinsey said. “Think of the poor people already starving and begging for food rations. There was no way they were going to willingly give up a meal, unless it was for the church.”

According to Kinsey, eating disorders remained a classist problem, recorded as mainly afflicting the elite until 1973 when a book on anorexia was published by psychoanalyst Hilde Bruch.

Bruch’s book allowed the general public to become more familiar with eating disorder cases, and reported cases of anorexia nervosa, in particular, spread beyond the upper class, escalating in numbers through the 1970s and 1980s, Kinsey explained.

In a 2014 report about the state of eating disorders among women and girls, the Public Health Agency of Canada revealed an overall incidence of 1.5 per cent in 2006 — the most recent data available. The report also points to the need for high-quality data on eating disorders.

The social media link

Now, as many people are tethered to their smartphone, researchers are beginning to study how social media impacts eating disorders.

Andrea Lamarre, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Waterloo, focused on the representations and perceptions of eating disorder recovery for her PhD dissertation, and found social media could be problematic for individuals attempting to recover.

[Timeline of the history of eating disorders merged with a timeline of body ideals © Meg Sutton and Sarah Tsounis]

Last year, she conducted a study examining how the recovery process from eating disorders are displayed on Instagram.

“People in recovery who are posting on Instagram tend to be thin, tend to be white, and tend to … [have] a body that is generally acceptable in society. And that could possibly be problematic because not everybody who experiences an eating disorder is thin, white, young in appearance,” she said.

M.T. identifies with this assertion, describing herself as someone whose body mass index (BMI), a tool often used to classify anorexia, categorizes her as obese.

“There were male patients in my treatment centre suffering from anorexia just like the rest of us,” she added. “Girls get off easy — they can be thin, or busty with booty now. But I feel like guys are always targeted for not having enough muscles, or not being athletic, or not looking like they walked off the set of Baywatch.”

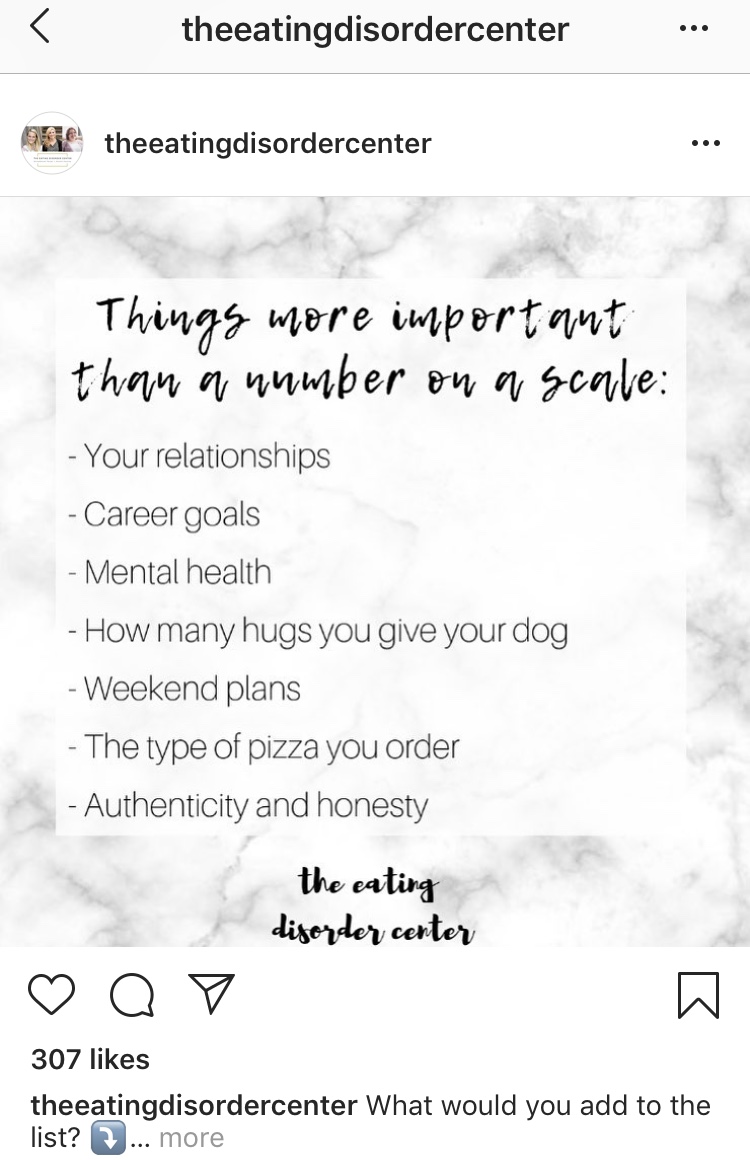

[Graphic © Meg Sutton]

A 2017 study also concluded that Instagram can contribute to body image issues. The study, in the journal New Media and Society, found a link between Instagram use and increased self-objectification behaviours in women aged 18 to 24. This self-objectification, described by the authors as when individuals view themselves as a collection of body parts, can lead to body shame, appearance anxiety, and disordered eating. It is also related to a prevalence of “fitspiration” or “fitspo” posts — a hashtag commonly captioned on images detailing body-image-based fitness goals.

Another study published in the International Journal of Eating Disorders from 2016 associates “fitspiration” with other eating disorders, including compulsive exercising, body dissatisfaction, anorexia, and bulimia nervosa — an eating disorder characterized by a restricting, bingeing, and purging cycle.

“While fitspiration posts alone cannot cause an eating disorder — they’re much more complex than that — poor body image and low self-esteem can be triggering factors to these serious mental illnesses,” the study found.

That means the goal of achieving a ‘fit’ figure for male or female bodies is a driving force behind the idealistic pictures on social media.

The overall conclusion from these studies is that if someone is recovering from an eating disorder, platforms like Instagram can be harmful, as Lamarre said.

“We have very strong messages that [are sent] out in the world around what you’re supposed to be doing, what you’re supposed to be eating,” Lamarre said. “And those messages are often in direct contradiction with the kind of messages that people receive when they are trying to recover from an eating disorder.”

She used the concept of eating a slice of chocolate cake to explain some of these feelings constantly contradicted on social media. In a meal plan for recovery, for instance, she said chocolate cake may be used as tool to teach individuals that it is okay to eat foods dense in calories.

“Whereas in society in general, eating a slice of chocolate cake would be seen as some sort of indulgence or often framed as something that you shouldn’t do,” she explained.

So on social media, there is a double standard of posts that sometimes celebrates and sometimes shames people based on their diet. They are encouraged to “eat cake for breakfast” but also conditioned that “cutting sugar leads to cutting fat.”

Finding a place for online communities

For those facing body image issues, Lamarre called Instagram “a double-edged sword.”

“On the one hand, [it’s] fantastic that people want to share their stories on Instagram, fantastic that people are finding strength and power in the community that exists on there for recovery,” Lamarre explained. “But on the other hand, it would be awesome to see more representation from more types of bodies in recovery from eating disorders.”

Lamarre said she believes policy changes and body diversity are necessary to make Instagram a supportive and safe space for those in recovery.

Currently, Instagram encourages people to report inappropriate content and provides the user with resources they can access to seek help, like helplines. The company faced calls early this year to block “pro-anorexia” — known in short as “pro-ana” — images in the same way self-harm images are censored.

But this practice is controversial because it can be implemented on people in recovery: Often, accounts of people who are in recovery are censored by Instagram as “pro-anorexia” content, Lamarre added.

“If we are going to censor a particular hashtag, I do think it’s really important that we provide some other space where people can go and talk about what they are experiencing in a way that doesn’t make them feel like they’ve done something wrong.”

In addition, Lamarre said “it would be awesome to see more representation from more types of bodies in recovery from eating disorders” to make the Instagram community welcoming to a diverse range of bodies.

Key to Lamarre’s research in eating disorders is the idea that recovery is “not something that’s done on your own, in this sort of vacuum.”

“It’s something that you do with people to support you, people who are challenging you,” she said.

An individual named Sophia praised Instagram for its “powerful” role in her recovery in a blog post for Beat Eating Disorders U.K. in 2017.

Video of Instagram’s content warning when searching #anorexia [Screen capture © Meg Sutton].

“If we are going to censor a particular hashtag, I do think it’s really important that we provide some other space where people can go and talk about what they are experiencing in a way that doesn’t make them feel like they’ve done something wrong.”

“People like @TheFoodMedic and @doctors_kitchen have played a part in how I see food, which is to heal and fuel and to boost my mood and energy levels,” Sophia explained. “Now I am able to work out for fun, not for punishment or a picture.”

But because recovery isn’t easy, she said, there are slip-ups.

“If one person falls, we could all have the potential of avalanching down. Like if someone posted about their weight,” Sophia wrote. “But it was about making sure those feelings didn’t last and encouraging one another to keep going towards recovery.”

It’s this sense of community support created on Instagram that Lamarre said is a crucial piece in the eating disorder recovery puzzle, making social media a tool that can be used to help or harm.

[Triggering Anorexic Content on Instagram, pre-update and censor © Instagram]

[ Recovery Community Post © Instagram ]

[A post tagged #fitspiration © Instagram]