The price of pollen

With temperatures rising, ragweed is on the move and North Americans are spending more than ever on allergy reliefBy Sarah Kazak

Itchy, watery eyes, scratchy throat, runny nose, coughing, sneezing and to top it all off, the joys of being congested. Those who suffer from seasonal allergies know the symptoms all too well.

A variety of pollen-releasing plants are responsible for triggering seasonal allergies, which generally flare up every spring. But the one that wreaks the most havoc — ragweed — saves its worst effects for the fall.

Ragweed pollen, which can cause seasonal allergenic rhinitis, more commonly known as hay fever, is one of the most common chronic health conditions impacting North Americans. It affects 10 to 20 per cent of Canadians and as many as 23 million Americans, according to the Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Society of Ontario and the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

In fact, ragweed is the offending allergen for about 75 per cent of hay fever cases, according to a 2010 report by the National Wildlife Federation.

But if ragweed is a debilitating nuisance for so many today, experts suggest it’s only going to get worse. Thanks to a changing climate, ragweed is growing for longer periods of time and spreading to new areas. Longer summers and warmer falls are forcing North Americans to spend more money than ever before on allergy relief medication.

In fact, the impact on the annual pollen season can already be measured, says Dr. Anne Ellis, associate professor and division chair of Allergy and Immunology in the department of medicine at Queen’s University and the director of the Environmental Exposure Unit in Kingston. “We do know that climate change is altering the pollen season,” says Ellis. “We are starting to see pollen season start earlier in the year, particularly in the spring, compared to previous years because of the increase in temperatures in North America…”

From 1995 to 2015, ragweed season increased by 25 days in Winnipeg, Manitoba; 24 days in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan; 21 days in Fargo, North Dakota; and 18 days in Minneapolis, Minnesota, according to a study by the United States Environmental Protection Agency. Often what happens with ragweed in particular, says Dawn Jurgens, director of operations at the Aerobiology Research Laboratories in Ottawa, is that the season starts in late July and then peaks sometime in mid-August. Once it has peaked, the (pollen) levels drop and they remain the same until the first frost, she said.

“If the first frost keeps getting pushed later…then obviously its stands to reason that it will cause those low levels to continue longer.”

Ragweed is spreading

Every plant has a natural range that is partly a function of climate, says Stephan Gruber, associate professor at Carleton University and Canada research chair in climate change impacts/adaptation in northern Canada. “With climate change you can expect the range of some plants to change, for example, some plants may go a little further north than they have been before depending on the temperatures.”

He says while some plants may no longer be able to survive in their place of origin because of changing weather conditions, it may become ideal for another.

“Ragweed range has increased in my lifetime quite a bit,” says David Miller, a chemistry professor at Carleton University who has held an NSERC Industrial Research chair in fungal toxins and allergens. “I am from New Brunswick and when I was [in my twenties], ragweed didn’t exist in New Brunswick and it does now. In fact, I am allergic to ragweed and I wasn’t until I lived in Ontario after 7 years.”

“I would say that this is something that is happening perhaps in areas that are not really established right now, so in places like Saskatchewan and Alberta,” says Jurgens. Since ragweed is not native to the prairies, she says when looking at data from 2000 to 2016, the amount that has started to grow indicates that perhaps the range is expanding.

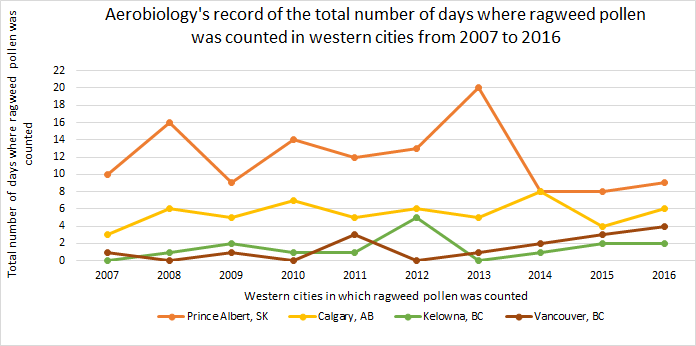

For example, in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, there was only enough ragweed pollen to count for 10 days in 2007 versus in 2013 where there was enough for 20. This is also the case in Calgary, Alberta, since the 2007 data shows that ragweed pollen was counted for three days versus eight days in 2014, according to Aerobiology data.

Data provided by Aerobiology.

However, Dawn suggests that while it is plausible that climate change is playing a big role in intensifying seasonal allergies, there can be other factors at work too. Since there are so many things that interact within nature, she says it is hard to say that one thing plays a bigger role than another. “I would definitely say that (climate change) is important and probably contributing to (an increase in ragweed)…but (an increase) could be due to many different things.” She says it could also be related to “an elevation of carbon dioxide levels, or something as simple as a decrease in competition of different types of weeds, or a decrease in a specific bug that eats ragweed.”

About ragweed

About 17 widely-distributed species of ragweed are found in North America, according to Pollen.com, an allergy forecast website run by IMS Health. Short or common ragweed, scientifically known as Ambrosia artemisiifolia, has lacy and palmate leaves with parts diverging from a common base, like the fingers of a hand. Its flowers grow in a spike that extends vertically above the leaves and it can measure anywhere from a few inches to more than 12 feet in height.

The soft-stemmed weed is tough and is able to survive in many places, especially where soil disturbance occurs like in construction sites, along the margins of agricultural fields, along roadways, and near riverbanks that usually change during each spring snow melt and runoff, according to the allergy website.

Common ragweeds only live for one season, however, during that time, each plant alone produces up to one billion pollen grains, according to the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America’s New England Chapter.

This is concerning because not only is ragweed season getting longer, it has been estimated that symptoms after exposure to ragweed pollen can begin with concentrations of as few as five to 20 pollen grains per cubic meter, according to a 2008 study published in the Allergy, Asthma, and Clinical Immunology journal.

“If the seasons are getting longer and if the range of ragweed is expanding, there is going to be more people at a farther reach that are going to be affected and therefore buying (allergy-related) drugs,” says Daniel Coates, director of marketing and business development at the Aerobiology Research Laboratories in Ottawa.

Over the last four years, the number of North Americans suffering from seasonal allergies has increased approximately 15 per cent, according to Coates.

Photo of ragweed provided by Aerobiology.

The price to pay

“People really take this seriously because it is responsible for the biggest single over-the-counter spend of medication,” says Miller.

Every year in the United States, hay fever costs Americans over $11 billion dollars in medical costs and more than $13 million in doctors’ visits. There are more than four million missed or low productivity workdays and over $700 million in lost productivity due to the allergy, according to the National Wildlife Federation.

“There is a direct correlation between sickness and productivity,” says Coates. “Allergies affect people’s health, and once they get sick from those allergies, they are away from work and that has a big economic impact.”

As for how to best deal with seasonal allergies, Ellis says those suffering should always start with second-generation non-sedating anti-histamines such as Reactine, Claritin or Aerius, along with prescription nasal corticosteroids. However, if an individual is suffering from more severe symptoms, he or she should consult with an allergist about more targeted relief from an allergen-specific immunotherapy, administered through an allergy shot.

Looking to the future, “we are developing newer and better specific immunotherapies…with better side-effect profiles,” Ellis says.

About one in 1000 individuals risk suffering from a full-body or anaphylactic reaction from allergy injections, she adds, “so it would be nice to have safer treatments that require fewer injections.”

And with climate change now contributing to the spread of ragweed pollen and other seasonal irritants, a growing demand for allergy relief is among the easiest trends in the pharmaceutical industry to forecast.

For example, “Canadian havens from hay fever,” published by Agriculture Canada in 1976.