The Heart of the Matter

There are plenty of awareness campaigns surrounding women’s heart health,

yet statistics still show women are not being properly treated for heart disease.

By Taylor Barrett

On Dec. 23, 2016, actress and author Carrie Fisher, 60, boarded a plane from London to Los Angeles. About 15 minutes before that flight landed, she went into cardiac arrest after she stopped breathing for roughly 10 minutes, according to witnesses on the plane. Prior to that, she showed no other symptoms.

After four days on a ventilator in the intensive care unit, Fisher died.

Following her death, amidst all the tributes to her career, a handful of articles were published discussing heart disease in women: what the risks and symptoms are, and how women can protect themselves. There is nothing new about this information. Yet the numbers suggest the message still isn’t getting through.

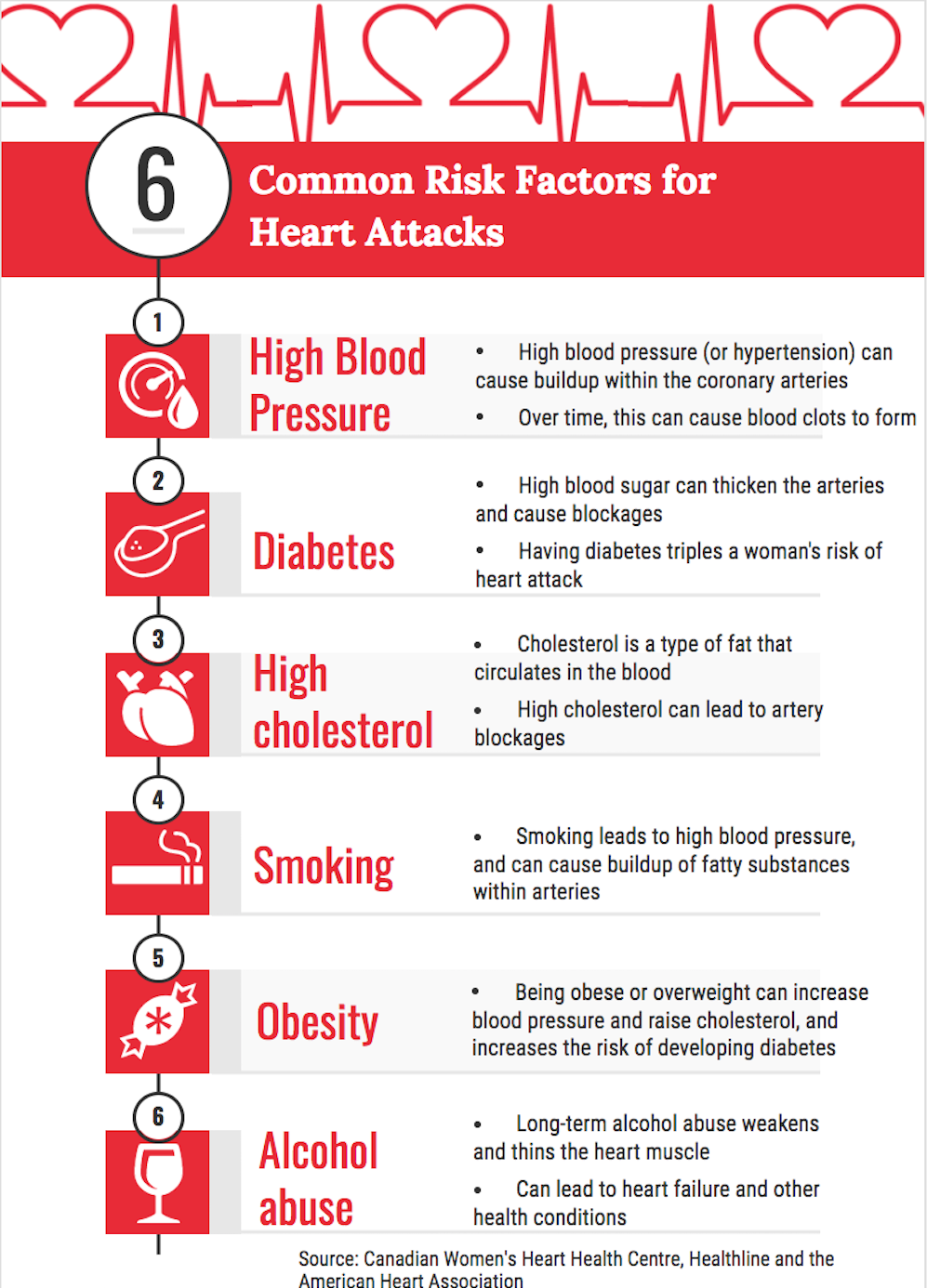

According to the Heart and Stroke Foundation, women in Canada are 16 per cent more likely than men to die after a heart attack, and about 36 per cent more likely to die of stroke. Like Fisher, roughly 64 per cent of women who die suddenly of coronary heart disease had no previous symptoms, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Research published this year from the George Institute for Global Health and the University of Sydney in Australia found women were significantly less likely to be assessed for heart disease risk factors. Most shockingly, heart attacks and strokes kill twice as many women than all cancers combined, according to the World Heart Federation.

In spite of numerous awareness campaigns surrounding women’s heart health—including the Heart and Stroke Foundation’s popular Heart Truth annual fashion show and the American Heart Association’s Go Red for Women campaign—and a conference devoted to the issue, it appears that many women who should be screened for symptoms of heart disease are not. It’s a difference they are paying for with their lives.

Greg Killough, project lead for women’s heart health research at the Heart and Stroke Foundation based in Ottawa, says awareness campaigns are only part of the story.

“Women are focused on a number of different health issues, heart disease and stroke being one of them,” Killough said. “Where there is maybe a disconnect is that women don’t understand that heart disease and stroke are more deadly for them than they are for men.”

Physical differences between men and women

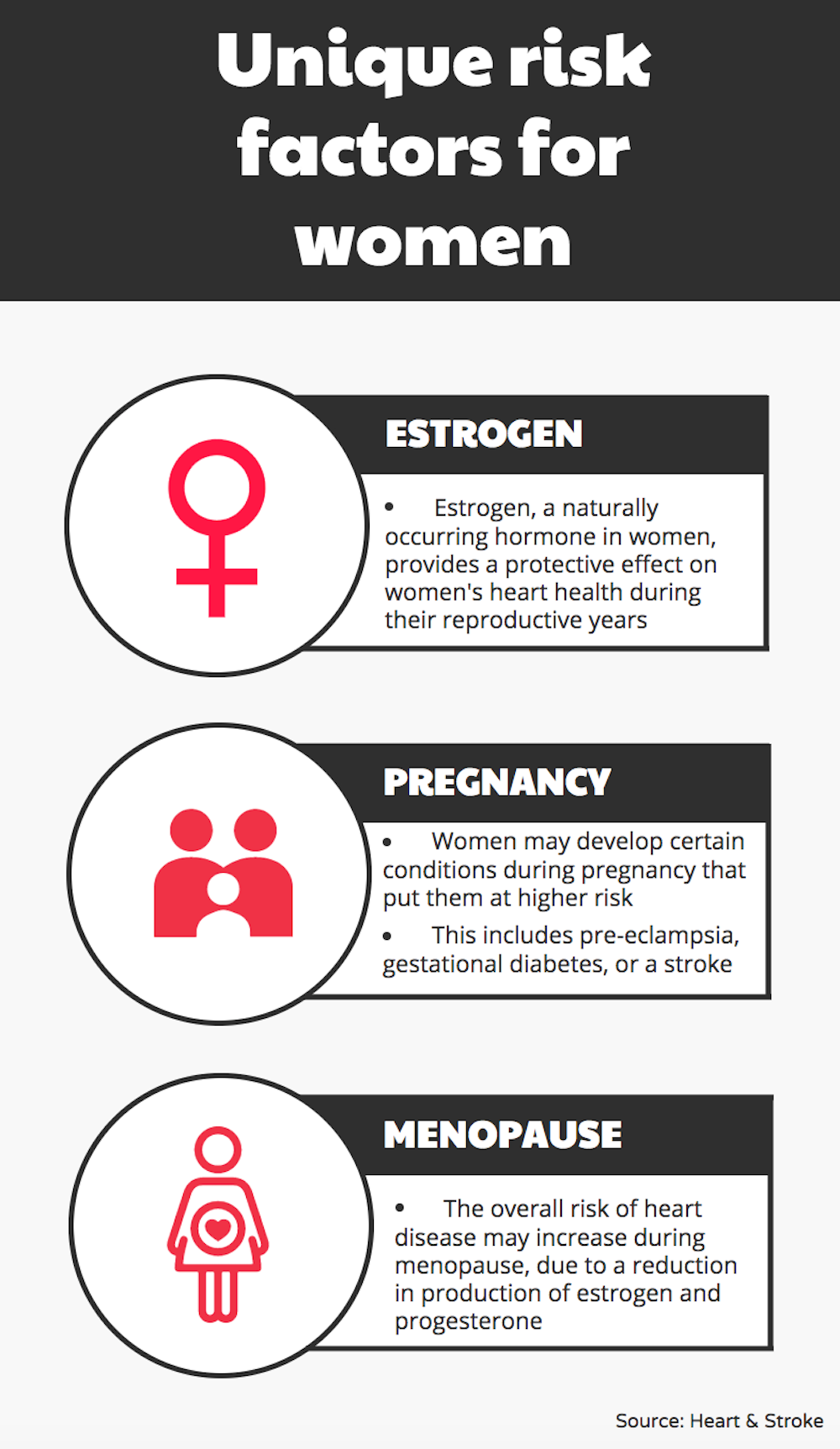

Women typically have smaller hearts and arteries and higher heart rates. Male hormones enlarge arteries, but female hormones make arteries smaller, which leaves women more prone to blood clots and blockages. Female arteries are also more difficult to repair for the body.

Lisa McDonnell, project manager for the Canadian Women’s Heart Health Centre based at the University of Ottawa Heart Institute, has noticed an information gap when it comes to these details. When she and her team were forming the centre, they surveyed Canadian women on beliefs and practices surrounding women’s heart health. On tests marked out of 40, the average score was 15.

“We didn’t expect women themselves to be that unknowledgeable,” she said. “There was this huge difference in perception versus reality.”

Another key component surrounding awareness is misperceptions about women’s risk—women fail to recognize their own vulnerabilities surrounding heart health.

“Most of the time I get people saying, well, that’s odd, women are the usually the ones that look after the health of their families,” McDonnell said. “But it just goes to show they might be able to recognize it in other people but not themselves.”

“It’s just not a matter of build it and they will come,” she added. “A lot has to go into not just informing them but there’s that extra step of helping them personalize that risk.”

When women underestimate their heart attack risk it can lead to symptoms of heart disease being unrecognized or misdiagnosed—particularly because the traditional framework for diagnosing and treating heart attacks is based on the male physiology.

“Seventy per cent of what we know about cardiovascular disease is because the research was conducted in male subjects,” McDonnell said. “Our therapeutic and diagnostic strategies for heart disease and heart health are based on a male model of how it presents.”

Women’s symptoms are not all that meets the eye

Heart disease is generally perceived as a man’s illness—one of the largest misconceptions surrounding the disease. Men present with heart disease symptoms seven to 10 years earlier than women do, and by the time women show signs, it becomes more of a grey area because they often have other complications unrelated to heart disease.

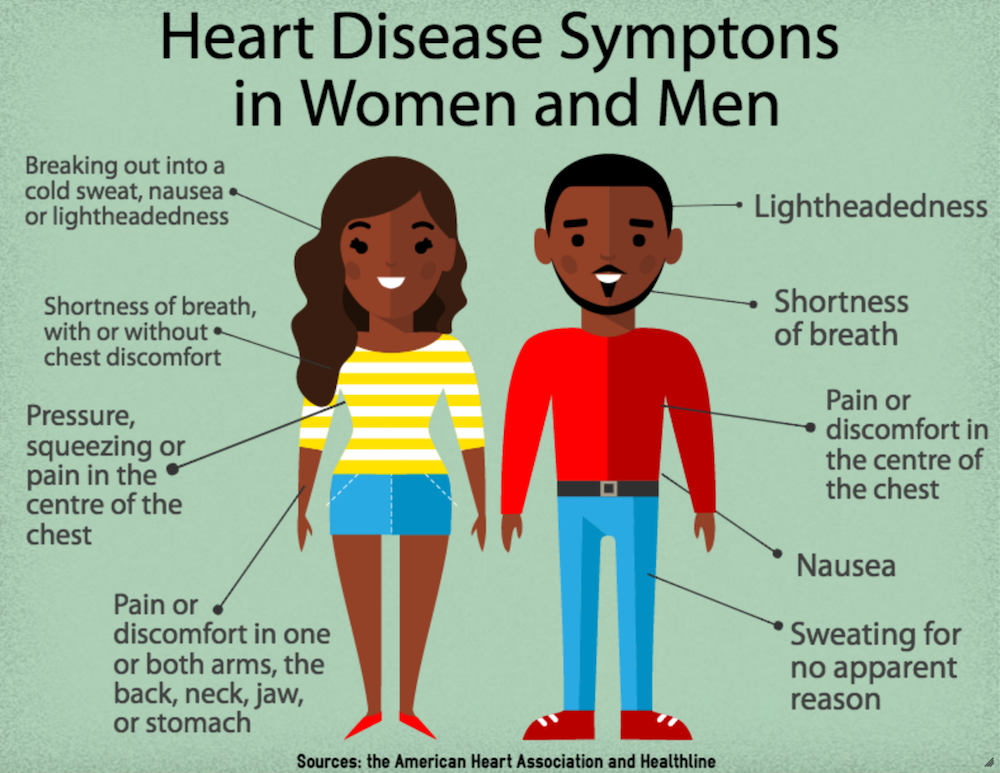

In women, heart disease presents atypically compared to the classic Hollywood heart attack: sharp chest pain, shortness of breath, lightheadedness, and arm pain—illustrated by the late comedian Redd Fox’s famous routine.

Primarily, women have different types of heart disease that are exclusive to them, and other types of heart disease that present in women more often than men.

Female hearts respond differently to physical and functional changes after heart disease. Generally speaking, women are more likely to suffer strokes and develop heart valve disease than their male counterparts.

Women’s symptoms also differ compared to men. Women tend to present with aches and soreness that can feel like upper back pain, fatigue, shortness of breath and neck or jaw pain. Plus, females with heart attack symptoms will likely have normal results when tested with standard heart attack treatments.

“Oftentimes we’ll hear stuff like ‘it felt very much like flu-like symptoms,’” McDonnell said, adding that anywhere from 26 to 54 per cent of women who present with theses symptoms are either discounted or ignored.

On the healthcare provider side, McDonnell said new doctors have a difficult time recognizing atypical symptoms because of the standard treatments based on the male body.

“They’re saying, yeah, well you know, a heart’s a heart,” she said. “Well, no it’s not because women have different types of heart disease that are much more prominent versus what we see in men.”

Heart attacks and strokes kill twice as many women than all cancers combined.

The beat goes on

As for the future of women’s heart health, the Canadian government has shown an interest in boosting research. The federal budget—announced on March 22—included $5 million given to the Heart and Stroke Foundation over the next five years to support women’s heart health research.

In the last 10 years, more research has been done on women’s heart health in Canada, which started when researchers noticed more women were dying of heart disease compared to men—30 per cent versus 28 per cent, respectively.

“We’re really looking to grow the knowledge around women and heart health and really foster collaboration and innovation within Canada to further our knowledge and to put that knowledge into practice,” Killough said. “Public education and awareness is really critical to what we do.”

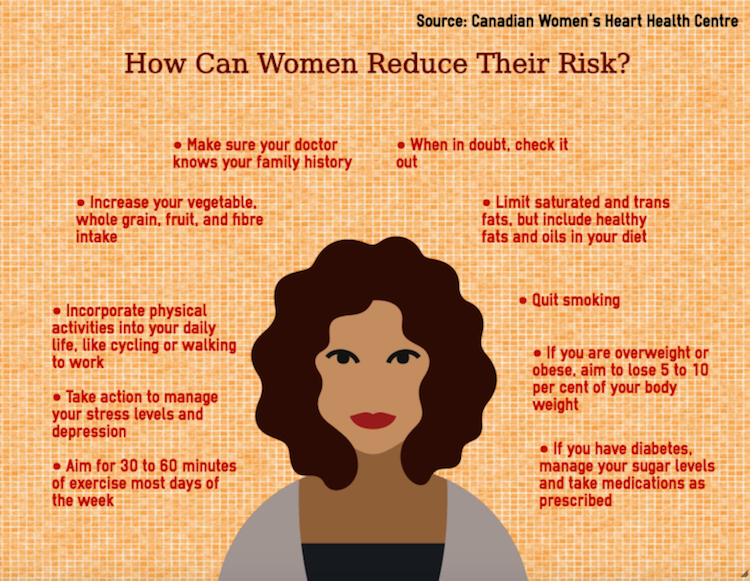

On the health side, McDonnell said starting a conversation around women’s heart health is the most important step—80 per cent of heart disease risk can be managed through health practices and behaviours within an individual’s control.

As well, women should be aware of their own risk profile on a yearly basis and be willing to advocate for their own treatment. McDonnell says women need to keep tabs on changes in test results, such as blood pressure and cholesterol.

“It’s your body, they’re your numbers,” McDonnell said. “Make sure you understand what they are because even the slightest creep up in a number could make a dramatic difference.”

“There’s one thing to treat a patient once they’ve presented themselves to you, but oftentimes that’s too late.”