Tourette’s therapy

Tried, true, and tricky to try

By Julia Paulson and Martin Halek

Researchers look for new Tourette’s therapies as current best-standard treatments remain tricky to access.

At her Montreal psychology practice, Kelly Ann Cartwright sees patients who suffer from conditions that can be hard to discern from the outside— anxiety, depression, trauma, grief. But Cartwright’s specialty is a more visible condition that she has herself: Tourette’s.

“Growing up making movements and noises that are laughed at— in the media, sometimes stereotyped, stigmatized— you learn to hold it in,” said Cartwright. “If we do manage our tics, people around us don’t know the cost of that— they have no idea how hard it is, and of course we don’t tell them, because we’re scared.”

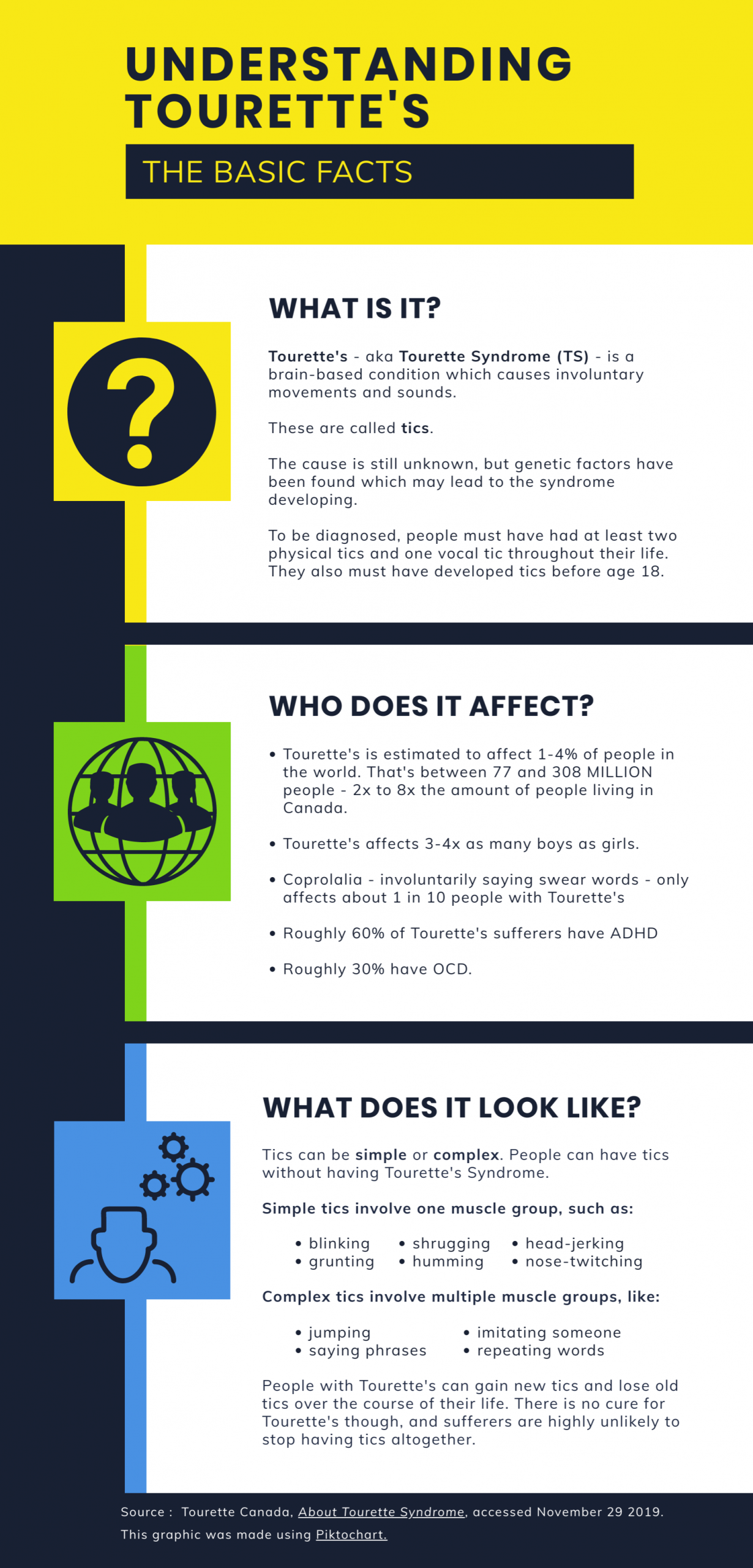

Tourette syndrome is a neurological disorder characterized by sudden, involuntary sounds or movements, known as tics. It’s estimated to affect between one and four per cent of the population. For people with Tourette’s, the urge to tic feels similar to a sudden itch. When they try to ignore it, the urge intensifies until it’s almost unbearable. And like scratching an itch, performing a tic provides brief relief, but makes the urge come back worse.

The leading treatment for tics is a form of habit-reversal therapy, but it has drawbacks. Researchers at Yale University have been studying whether a technique involving real-time brain imaging might form the basis of an additional treatment. This method, called neurofeedback, might teach people to control their own brain activity.

[Story continues under infographic.]

Tourette’s was first reported by French neurologist Gilles de la Tourette in 1885 after observing several patients with similar symptoms. He speculated the condition was rooted in the biological functioning of the brain.

In the early 20th century, researchers believed the condition’s root was psychological, seeking to cure it using psychoanalysis. It was not until the 1970s that Tourette’s was widely accepted as a neurological condition, being added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 1980.

The exact cause of Tourette’s is unknown, but genetics play a definite part. A 2017 study published in Neuron found four specific gene variants strongly associated with the risk of developing Tourette’s.

“The evidence shows that Tourette is one of the most heritable neurodevelopmental disorders,” said Paul Sandor, director of the Tourette Syndrome Neurodevelopmental Clinic at Toronto Western Hospital.

According to Sandor, identical twins have about a 80 per cent chance of both inheriting Tourette’s, compared to 25 per cent in fraternal twins.

“This indicates that genetic factors contribute about 60 per cent to an individual developing TS, while the rest is probably environmentally determined,” he said.

There is no known cure for Tourette’s. Until the early 2000s, medication was the only means of treating tic disorders such as Tourette’s. According to Sandor, medications such as antipsychotics can be effective at suppressing tics, but are used less often today due to adverse side effects.

Instead of medication, practice guidelines published this year recommend Comprehensive Behavioral Intervention for Tics (CBIT) to the majority of patients seeking treatment for their tics. It’s a form of therapy which trains people to manage tic urges without medication or equipment, its effectiveness highlighted in a 2019 review of scientific evidence.

With CBIT, patients learn to recognize that itchy urge to tic as it builds in their body. They’re also taught why indulging it can actually make their tics worse.

CBIT doesn’t teach people with tics to suppress their urges. Instead, it provides them with the tools they need to ride out those urges, explained Kim Edwards, one of two psychologists in Canada certified to train other professionals in CBIT.

Patients retrain their brains using competing behaviour – physical actions which make it difficult to perform their tics, such as holding their hands together if their tic involves clapping.

They also learn how their environment can worsen their tics. They practice relaxation techniques and are encouraged to educate their friends and family about ways they can help take the spotlight off their tics.

For Cartwright, CBIT combined with relaxation techniques played a key role in improving her tics. “My level of preoccupation with my tics is now very small,” she said.

Despite being highly recommended by medical guidelines, CBIT does have some major drawbacks. Very few psychologists are trained in it, which means long journeys and long waitlists for patients.

It’s also expensive. In Ontario, Toronto Western Hospital offers CBIT treatment in a hospital setting. Programs like this are rare. Many patients must turn to private psychologists, which aren’t covered under provincial health care plans. Although some psychologists offer a sliding-scale for low-income patients, paying out-of-pocket– even at reduced rates– can affect patients’ livelihoods and isn’t always an option.

For people who can’t access CBIT directly, there are do-it-yourself online resources such as TicHelper and the Leaky Brake Toolbox. However, the mental retraining required to overcome the urge to tic can be difficult without outside support.

“I don’t think [self-help] is actually as effective as having a therapist there to walk you through everything,” said Edwards. However, Edwards acknowledged that self-help is better than nothing for patients who can’t access CBIT.

Most importantly, CBIT doesn’t work in all cases. For Tourette’s activist Melissa Water, resisting her urges full-time is impossible. She only attempts to suppress her tics in specific circumstances. This normally amounts to postponing tics for a short time.

“When I’m passing a group of children, and I feel profanity coming up, I try to hold off until I’m past them.”

The fact that CBIT is not successful for all people with Tourette’s has motivated researchers to develop other treatments.

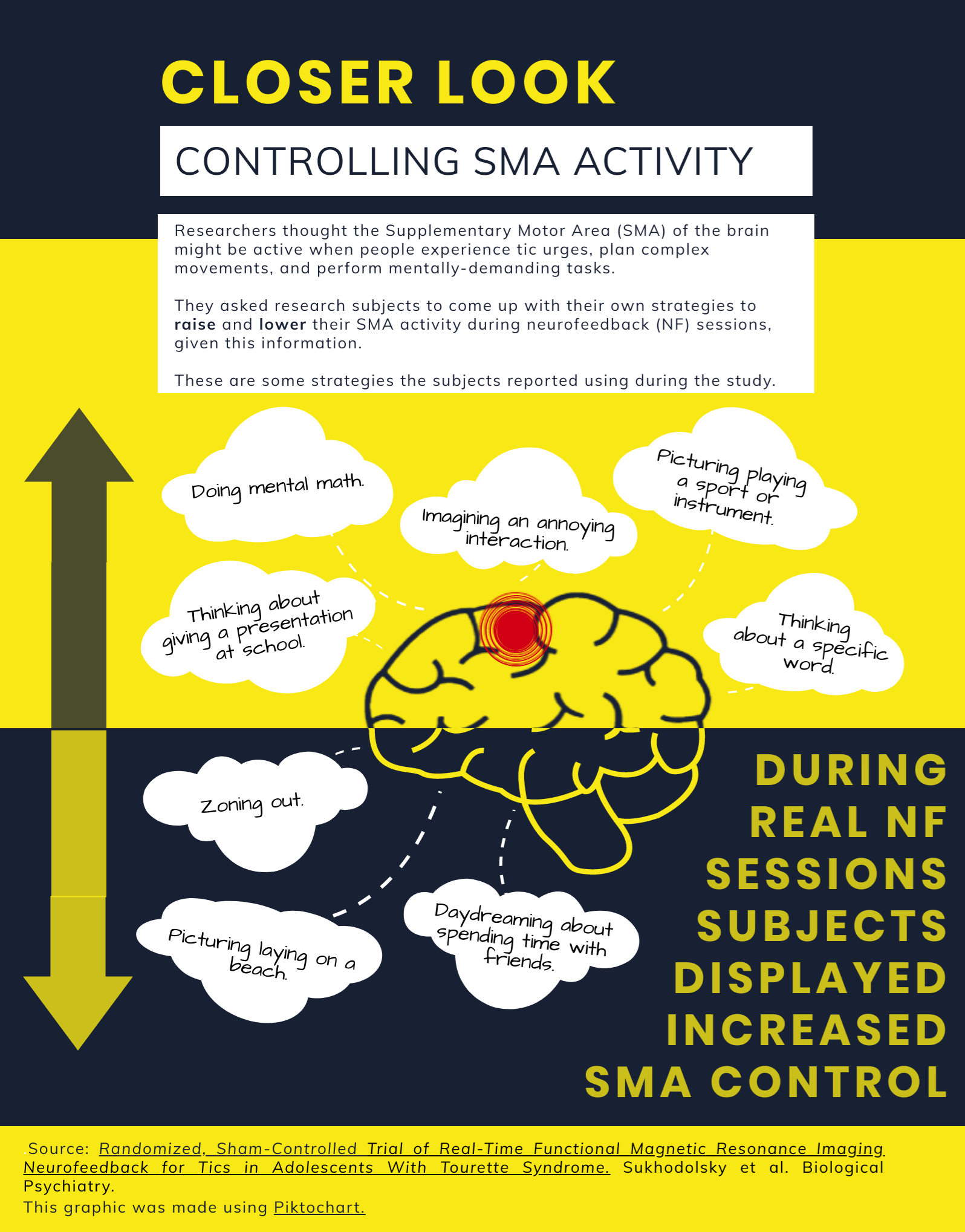

Instead of CBIT’s method of reducing the urge to tic by changing physical activity, what if patients could change their brain activity instead? Michelle Hampson and her fellow Yale researchers tried to answer this question with the first clinical trial of a treatment called real-time fMRI neurofeedback (rt-fMRI-NF).

Researchers know that stimulating a region of the brain called the Supplementary Motor Area (SMA) with electrical impulses can cause tic-like behavior and urges. This implies activity in the SMA may be linked to Tourette’s.

Using rt-fMRI-NF, researchers–and patients–can observe real-time SMA brain activity by monitoring blood flow to this area. The information appears as an updating line graph. Peaks in the line mean more blood flow (and more brain activity); dips mean less. The ultimate goal is for patients to develop personal mental strategies which lower their SMA activity, such as picturing calm scenes, or zoning out. Hampson and her fellow researchers believed this could reduce Tourette’s symptoms. Their study’s results were published this year in Biological Psychiatry.

In a trial that included 21 adolescents with Tourette’s Syndrome, the researchers found that subjects experienced a significant drop in their tic severity following real neurofeedback treatment, as opposed to sham neurofeedback treatment.

The average tic severity score dropped by 5.27 points in a group of subjects who received real neurofeedback, while the score of a group who received sham neurofeedback decreased by only 1.5 points. Additionally, a clinician (who did not know which treatment subjects had received) rated five out of 11 subjects in the real group as “very much improved.” None of the 10 subjects in the sham group received this rating.

These results suggest neurofeedback treatment worked to reduce some Tourette’s symptoms.

Overall, the study’s findings are promising, but they need to be replicated in larger trials to prove SMA neurofeedback is widely effective. In the meantime,

Hampson and her fellow researchers are working on refining the treatment approach. They’re analyzing their fMRI data for any other areas brain activity which may have changed in response to the real neurofeedback sessions.

Considering how expensive, time-consuming, and challenging Tourette treatments can be, some people with the syndrome prefer to simply live with their tics.

According to Edwards, Tourette’s is the only disorder in the DSM which can be diagnosed without impairment.

“What that means is there’s a fair number of people who can be diagnosed with Tourette’s, but their tics don’t bother them at all.”

The 2019 guidelines for treating tics state an acceptable approach for patients who don’t feel impaired by their tics is to see if tics improve naturally instead of seeking treatment.

Even if the tics don’t improve, some people are choosing to embrace their Tourette’s, rather than trying to change it. Water rarely holds in her tics these days.

Tourette’s activist Melissa Water explains how living with Tourette’s does not have to define one’s life.

“I used to be very apologetic every time I would swear. At some point, I just had to accept it so I wouldn’t be embarrassed every time I did something I didn’t mean to,” said Water.

“If I start apologizing again, it puts me back into a state where I feel bad that I tic– and I shouldn’t do that, because it’s not my fault.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story included an infographic which mispelled Sukhodolsky’s name in its source citation.