What happens in the gut when we travel?

New traveller's diarrhea treatments may be on the horizon as researchers dig into the secrets of the gut microbiome

By Jordana Colomby and Matt Gergyek

Looking back on it now, Erin Hynes laughs about her and her partner’s bouts of

Hynes said she remembers being on a bus in Laos, a country in Southeast Asia, at the beginning of their trip. En route to Kuang Si, a famous waterfall just outside of Luang Prabang, the bus was weaving along a bumpy road, so the two were a bit queasy

“I don’t feel very good,” he said, and Hynes said she instantly knew what was about to happen.

For four weeks, Hynes and her partner took turns battling

There’s not one specific cause of

The inner workings of the gut microbiome — the collection of bacteria living in your intestines — are extremely complex. These resident microorganisms help humans digest food and fight pathogens. Bacteria hitchhiking on food and drink constantly enter and leave the gut microbiome. T

Escherichia coli, the main culprit for

Currently, the front line of protection against

But Dukarol isn’t technically a

Dukarol introduces minute amounts of inactive cholera bacteria into the patient, forcing their body to produce protective antibodies. Since the toxins produced by cholera are about 98

But in reality, that isn’t exactly what happens.

ETEC strains that produce this heat-labile toxin accounts for less than 10

Although Dukarol isn’t actually a defence against traveller’s diarrhea, it’s the closest thing travellers have to a vaccine. Riddle is one of the researchers working on developing a vaccine specific for traveller’s diarrhea, but it hasn’t been easy. “The [vaccines] we’ve been working on for the past 15 years have not come to fruition yet. But we’re getting smarter,” Riddle said.

Fighting the travel bug

Beatrix Morrallee is a nurse manager with Passport Health, a private travel health company with over 270 travel clinics across North America.

Morrallee said from her experience over 50

“We talk to every person about [Dukarol], but we tell them it doesn’t make them superhuman,” said Morrallee, who oversees all of the Passport Health’s 19 locations in Ontario. “Our job is to give [clients] all the options so they can make an informed [consensual decision] on what they want and what they can afford.”

Passport Health has two locations in Ottawa. The one pictured here is downtown on Albert Street. [Photo © Matt Gergyek].

Hynes took Dukarol but it didn’t stop the 29-year-old creator of Pina Travels, a travel site focused on budgeting and itineraries, from falling ill again and again.

“I was on a bit of a streak,” Hynes said. She hadn’t gotten ill for about a month and said she was feeling great when she arrived in Nepal — her second-last destination before returning home to Toronto. Hynes said she remembers hearing people in her hostel warn each other not to drink the free bottled water, but unfortunately, she had already made that mistake.

Over the next four days in Edinburgh, Hynes lost control of her bowels and found herself constantly darting to the washroom only to realize it was too late. “It was awful,” she said.

A photo from Hynes’s journey taken in Laos, a country in Southeast Asia. [Photo courtesy of Erin Hynes].

Morrallee said Passport Health recommends medications such as Imodium or Pepto Bismol for the first regimen of traveller’s diarrhea treatment and antibiotics when these treatments don’t work.

But antibiotics, if overused, can have a major downside: the global spread of antibiotic resistance.

“We’re in a losing battle against bacteria,” Riddle said. “It’s a tough battle and we continue to develop antibiotics to try to treat infections appropriately, so resistance does develop.”

As antibiotic resistance develops and spreads across the world, our medications become powerless and once-treatable illnesses can become fatal. Riddle said there are many ways drug-resistant bacteria can travel across country lines, like food imports and bird migration, but travellers can be vectors as well.

One of the controversies in the field right now is whether to take antibiotics for minor cases of traveller’s diarrhea or whether it’s best for patients to just ride out the symptoms and heal on their own. Minimal intervention has its own risks: Untreated, infected people might spread the pathogen to others and they are also at risk of developing chronic health problems connected to certain infections.

Campylobacter, one of the top three causes of traveller’s diarrhea, can lead to issues such as arthritis, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), or Guillain-Barré syndrome, which is an acute flash of paralysis, according to Riddle.

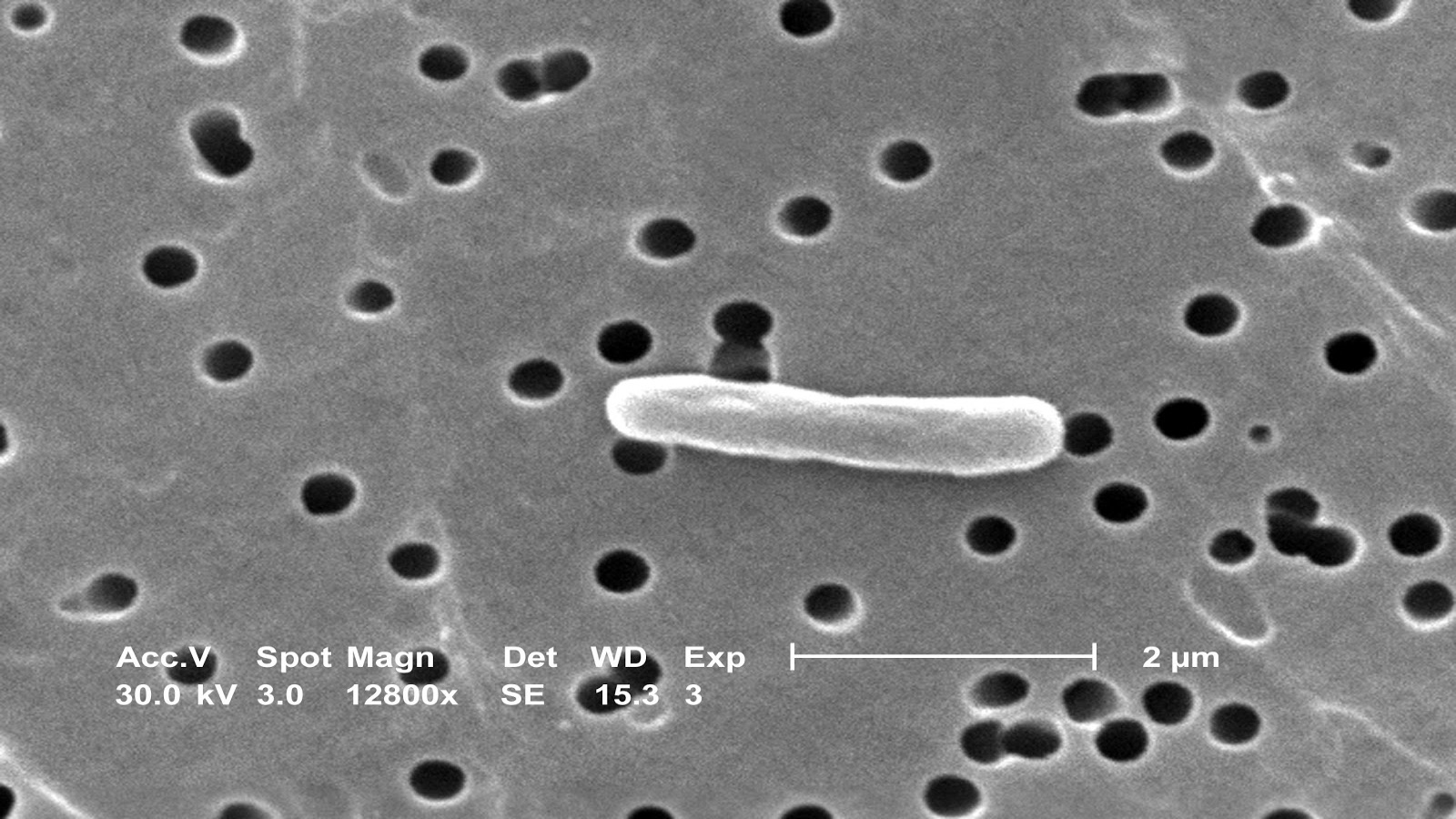

Bacteria of the Campylobacter genus, which causes about 15

Riddle said these “post-infectious cases [usually go] away in about six to 12 months, but in a certain percentage, say 30 to 40

While post-infectious diseases are a concern, most people’s microbiomes bounce back when they return home. Some people won’t even experience traveller’s diarrhea at all.

The gut microbiome inevitably changes with travel. Getting on a plane,

“You can have a change and actually have no illness, you could have

Whether or not you get sick depends not only on the pathogens introduced to your body but also on your initial microbiome, according to Dr. Brett Finlay, a professor of microbiology at the University of British Columbia (UBC).

Riddle found that approximately 15 to 20

“It’s a bell-shaped curve,” Riddle said.” You have people that are on the extreme of being more susceptible and [others who are] naturally protected.”

Even though we know some people are less susceptible to developing traveller’s diarrhea, researchers are just at the beginning of being able to translate that knowledge into treatments. At the moment, researchers are focused on understanding the basic

For example, scientists have been able to determine that some people’s microbiomes are better at fighting off and recovering from pathogens than others. They have started doing fecal transplants — transplanting the gut microbiomes found in poop from healthy individuals

Once researchers better understand the microbiome, they’ll be more adept at manipulating it to help prevent and cure traveller’s diarrhea — giving hope to