Cleaning up the scraps: What can improve Ontario's waste diversion rates?

With space at a premium, Ottawa is among the municipalities that must urgently cut down on waste flowing into local landfills.

By Alicia Wachon

There’s a mountain looming over the nation’s capital—a mountain of trash.

A new report has identified Ottawa as the second worst among 12 similarly sized Ontario cities at diverting waste from landfill sites.

“I was a bit disappointed to find out that we were as bad as we are,” says Duncan Bury, a co-author of the Waste Watch Ottawa report. He is part of the advocacy group that uses evidence to suggest ways of improving design, collection systems, policies and programs in Ottawa.

Waste diversion refers to any household or organic food waste that can be recycled or composted instead of ending up in a landfill.

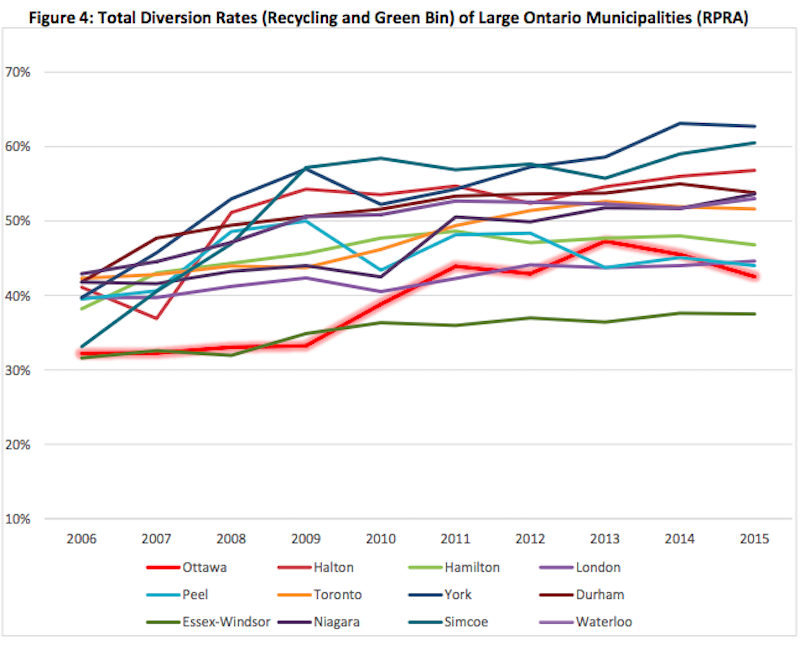

In 2015, Ottawa diverted 42.5 per cent of its waste. Only Essex-Windsor had a lower rate at 37.5 per cent. Ottawa’s 2015 diversion rate was also lower than its 2014 rate, which was 45 per cent. Though Ottawa is not far behind the overall provincial average of 47.7 per cent, it lags after other municipalities like Regional Municipality of York (York Region), which topped the 2015 rankings.

The WWO report believes that poorly performing systems are a result of not enough proper participation and a lack of education on what will happen if these rates continue to decline.

“It starts with looking at what we’re actually throwing out in the first place, and then thinking, how does that impact us in the long haul?”, says Bury.

[Photo © Waste Watch Ottawa Report, p.9]

Landfill life expectancy at risk

One major concern of the WWO report looks at the capacity of Ottawa’s Trail Road landfill site, which has a current life expectancy of 28 years.

“The argument and analysis [WWO] did, says that for every one percentage point [increase] to the existing waste diversion rate, such as 44 to 45, you get one extra year of life at the existing Trail Road landfill site,” said Bury. He says the odds of finding another site within the bounds of Ottawa are low because there is no room to fit another.

“Although 28 years in some ways seems like a long time, if you have to replace that site and find another one, this will be very expensive and difficult to do,” says Bury.

The report recommended how the city could easily increase their rates by improving the current collection programs rather than creating entirely new ones. To do so, they could enhance the collection frequency to prevent an overflow of blue box items. They could lower the limit on the collection of garbage as an incentive to increase participation, and could also create a ‘pay as you throw’ system that will discourage waste generation in Ottawa.

Duncan Bury, the co-author of the Waste Watch Ottawa report, says he believes that Ottawa has the ability to extend the capacity of the Trail Road landfill before it’s too late. [Photo © Clarissa Leir-Taha]

What happens to the environment?

In addition to to lengthening life expectancy, there are also environmental and health reasons to watch for in terms of restricting our waste diversion over time. As outlined in the Environmental Commissioner of Ontario’s report from October, Beyond the Blue Box called for immediate action on several environmental concerns that occur from improper waste disposal. Most of these concerns address either land or atmospheric pollution.

Firstly, rainwater that drips through waste can collect certain chemical pollutants and toxic materials that create a contaminated liquid called “leachate”. When landfills lack rigorous leachate collection systems, the report says the contamination affected surface water on the ground.

Another example of ground contamination is pure litter in the landfill. Besides the fact that it is costly to manage, it can pose risks to ecosystems and wildlife. As garbage breaks down, microscopic organisms ingest toxic chemicals into their body that can be passed throughout the food chain.

In terms of atmospheric pollution, the air itself is at risk when incineration takes place to make room for more waste. Particulate matter and pollutants such as dioxins released into the air cause human health problems.

Lastly, it is no surprise to that improper waste disposal also contributes to the already worrisome global issue of climate change. There are many ways that this occurs. For one, extracting resources each time produces carbon dioxide which is a common greenhouse gas. Transporting those products around the globe, as well as to the landfill when they cannot be reused, releases additional gases. Lastly, decomposing waste in landfills can cause uncontrolled fires and damage vegetation—again releasing emissions into the atmosphere and effectively speeding up the process of climate change.

New legislation

In 2016, Ontario passed the Waste-Free Ontario Act. It outlined a plan to maximize the province’s waste diversion by setting interim diversion goals to meet until Ontario manages to produce a significantly less amount of waste.

The primary change was aimed at large producers of waste from manufacturing industries to taking financial responsibility and collect their own waste made by their products and packaging.

“Under the previous framework, The Waste Diversion Act from 2002, … producers were not directly obligated to reduce waste, increase reuse or promote recycling,” says Lindsay Davidson, a spokeswoman from the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change.

In 2017, the province released the Strategy for a Waste Free Ontario report which introduced the concept of a circular economy. A circular economy aims to incorporate new designs of materials and products to be more environmentally friendly, which as a result, will maximize the overall amount of waste diversion. The report also says that the first few years of this process will be dedicated to setting the foundation for this shift in waste collection and will start by transforming the current programs.

“Making producers responsible for their products and packaging provides incentives to improve product design,” says Davidson.

The province thinks that if producers create packaging that is environmentally friendly, recovering these materials through their own collection services could also increase productivity that showcases a new design.

Financial relief provides municipalities relief

Waste management is no simple matter in Canada. Though it is regulated under provincial legislation, it still relies on action from the other levels of government. The federal government translates what is expected of the country from a global standpoint, while local municipalities manage the actual collection of waste.

In Ontario, there are generally two sectors of waste generation; the first being residential waste such as curbside collection or depot drop-off centres, and the other is an industrial, commercial and institutional sector (IC&I).

The Recycling Council of Ontario explains that municipal governments put by-laws in place for residential collection that aim to cut back on improper diversion. For example, some of these by-laws may include determining waste collection fees, setting specific bans on when materials can be brought to the landfill, or even monitoring the list of acceptable recyclable materials.

“Shifting costs of recovering product and packaging waste from municipal taxpayers to producers will also save money for municipalities and improve the sustainability of municipal services,” Davidson explained.

Currently, this is the issue that the municipality of Ottawa faces; too much financial responsibility that could be otherwise shared with the IC&I sector to develop higher diversion rates.

The city’s personal goal

Ottawa City Counsellor, David Chernushenko, is also the the Chair to the Environment and Climate Change Protection Committee. He has actively voiced that the committee is trying to understand why there is less participation for waste diversion, such as not properly sorting organics and the blue bins.

York Region has found that by implementing certain dumping bans and creating community center drop-off locations encouraged people to be more aware of what they were disposing of in landfills.

Angela Plant, an assistant to the committee, said, “Our office is encouraged by the Waste Free Ontario Act; 100% producer responsibility relieves pressure on municipalities who bare much of the burden to deal with an increasing diversity of products which are costly to recycle.”

“In fact, our overarching vision as a City is that, [b]y 2042, Ottawa will have room in its municipal landfill because as a community we improved our rates of reducing, reusing and recycling, and managed our assets wisely,” stated Chernushenko in a public letter.

According to the WWO report, majority of poor waste diversion occurs when citizens do not properly recycle their trash in the right bin.

[Photo above © Couvrette/Ottawa via Flickr. Photo below © Alan Levine via Flickr.]

“Making producers responsible for their products and packaging provides incentives to improve product design.”

Ontario’s waste diversion goals

Though provincial and municipal initiatives have started, the one problem that arises from elaborate plans to increase waste diversion, Bury says, is that timelines to implement these goals take too long. The Waste Free Ontario Report says it aims to hit interim diversion rates with a predicted rate of 80 per by 2050 if all plans stay on track.

But, at what cost does the environment suffer if the plans fall through?

“Big international companies aren’t necessarily going to change things just because of the citizens in Ontario. Maybe not even regulations in Canada. But, If [Ontario] broadens the scope of packages that can be collected in the blue box, the industry is going to have to do something with them,” says Bury.

He also says this could do wonders for the waste diversion rates across the province, and not just Ottawa.

“The province has still very clearly said, ‘We have a waste problem’. In many ways, nothing will change,” says Bury.

“Generally speaking…in Canada we still have relatively cheap disposal and in the case of Ottawa, we’ve got 28 years before we’re going to have an immediate crisis on our hands. In terms of what happens on the streets, a truck will come by and pick up a blue box as always. The big difference is who pays for it and who operates it?”