Insecurities of government contract work

John Yemen has worked part-time contracts over the last 16 years without benefits. © Jean Pierre Niyitanga.

Working part-time contracts can create both financial and job instability, leaving many government employees worried about retiring without enough savings.

That includes John Yemen, a 41-year-old who has spent 16 years of his career working various casual contracts with the federal government in Ottawa. He has lived a modest life and working short-term contracts with no employment benefits has left him worried for his future.

“You can’t really do much of planning,” said Yemen, who now works as an imaging technician at Library and Archives Canada. “Something like paying your mortgage, which requires having a certain sustainable income, is really difficult. If I was planning my career better, I would have tried harder to find a full-time job earlier in my career.”

When he started working in 1999, Yemen was aiming for a permanent job but couldn’t find one. He found a part-time job through an employment agency and went on from there. Because his contracts are not automatically renewed, sometimes he spends two years waiting for an employment agency to find another job for him.

“There is a seduction of working for an employment agency because they will do the work of finding a job for you,” said Yemen, who studied multimedia development at Algonquin College. When he doesn’t have a contract, Yemen gains extra income through the movie-screening business he co-founded with his friends.

According to Statistics Canada, a full-time worker makes a lot more on an hourly basis than a part-time worker: $23.08 compared to $13 in 2014. Similarly, the median wage for a permanent employee was $22 per hour in 2014, compared to $16 for a temporary employee.

Even though Yemen has been able afford day-to-day expenses, he always feels the pressure to be careful how he spends his money. He said not being able to save any money makes it impossible to plan big projects like buying a house or a car, or going on vacation. He says even seeing a dentist can feel like a financial burden.

He said he went four years without taking a vacation and when he got sick he wasn’t paid for the days he stayed at home. He said he feels he’s missed out on a good quality of life and considers himself a working-class person.

When Yemen turned 30, he started to think more about his future. He said he realized he needed to earn more so that he could afford a vacation, a house, a car and more importantly, a good retirement pension package. In 2014 he was able to get a term contract with LAC that provides him with the same employment benefits as permanent employees.

After getting a term contract, Yemen immediately decided to buy an apartment hoping his contract would be renewed so he could pay off the mortgage. And with the term contract, he was able to take a paid vacation for the first time in 16 years.

Joseph Coppolino is in the same situation. A graduate of Carleton University, Coppolino’s first one-year contract with Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada ends in December and the pressure is increasing as he looks for another job.

“It sucks,” he said. “There is a lot of work to be done but it seems like there isn’t enough money to spend on a permanent employee.”

The blame is on the changing economy

One way the government can cut their expenses is by hiring workers on short-term contracts – and they have a growing tendency to do so. Between 2006 and 2014, part-time jobs grew by 15 per cent while full-time jobs grew by only seven per cent in the same period, according to Statistics Canada.

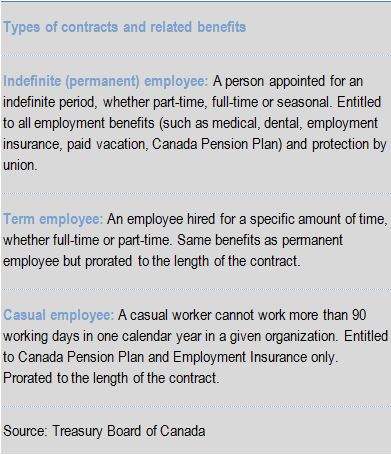

Professor Frances Woolley, associate dean and professor of economics at Carleton University, said the government doesn’t have the same obligations to part-time employees as they to their permanent workers..

“The system gives the government flexibility to bring in expertise they need for the time they need it and they don’t have to worry about what happens to that person after,” she said.

Woolley said the labour market has become increasingly competitive and there is a lot of downward pressure on wages. Woolley observed that the system is advantageous to employers who have the option to find a competent employee for a cheap salary.

“If they can find someone who is really good, get him under contract and pay him less without paying benefits, it’s much more attractive for the employer,” she said.

Economics professor, Frances Woolley, believes that young employees are vulnerable to a more competitive labour market. Photo Credit: Frances Woolley.

Woolley doesn’t see the situation changing soon, especially as technology transforms the economy and the nature of work. She said that with technology, it’s easier to get the work done with fewer staff compared to past years.

“My job right now as a university professor is to mark papers; there are people making computer systems that can mark students’ papers. In few years ahead it will be very easy to replace me by a computer system. There will be no need to pay me a salary,” she said.

The change in the government labour environment started with the 2008 recession. By 2014, the number of part-time jobs grew while full-time jobs declined. In 2008 there were 6,240 part-time jobs and in 2014 they were 9,206, according to the Treasury Board survey.

Luc Pomerleau, Gatineau Regional Representative for the Public Service Alliance of Canada (PSAC), one of the unions representing public servants, doesn’t think the hiring of part-time government employees affects his organization because few of them join the union. Currently, five per cent of PSAC members are part-time employees working on term contracts.

These are mostly former members who used to have permanent contracts. They may have decided to reduce their workload because of other commitments or they may have retired and come back to work as consultants.

This situation is a concern for young workers because the system gives advantage to experienced workers who can take up available jobs even after retiring.

“While some workers complain about part-time contracts, there are people who like that system,” Woolley said.