Mahamadou Taher Touré’s parents live in Bintagoungou, a small village near Timbuktu, Mali.

They are often afraid for their lives, says the Quebec physician. Malians look up to Canadians because Canada does not have a history of colonialism in Africa, he says.

The Canadian Armed Forces is going to Africa on a United Nations Peacekeeping Mission for the next three years. Canada might send its 650 troops either to Mali, the Central African Republic or Congo. If Canada’s forces go to Mali, Touré says, his parents and the general population will welcome them because the situation is escalating right now.

“They are an impartial third party that is useful to resolving conflicts,” says Touré.

The news of the new deployment raises questions about whether this new mission will put troops in harms’ way and not really effect any change on the terrain.

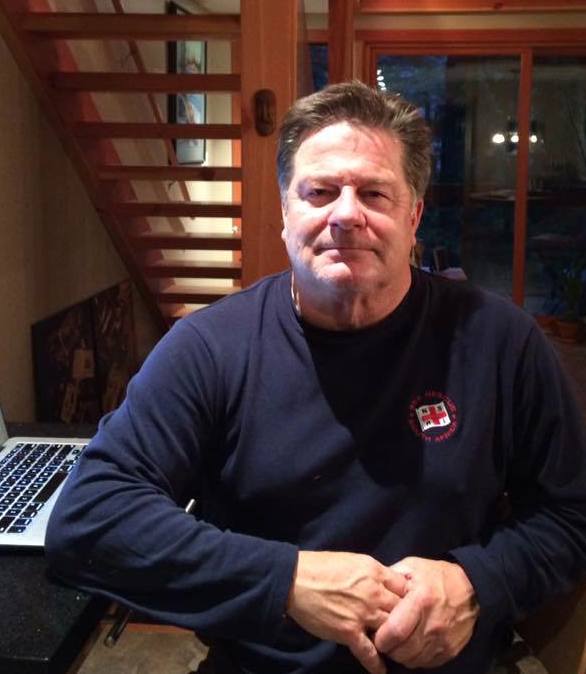

Do Canada’s UN peacekeeping missions do the good that is intended? Canada’s mission in Rwanda in the 1990s was not so successful, according to Jim Parker, a retired lieutenant who lives in Whistler, B.C. Parker spent six months with the peacekeeping mission in Sudan in 2008 and he said it was not what he expected it would be.

“We had no new tires, we were unarmed,” he says. “Some schools were left half-finished, some wells were left half-finished,” he says.

Moreover, the reports he would write about the locals’ situation were probably never read by anyone because nothing ever changed in the six months he was there, he says.

Parker says Canadians invented the term peacekeeping – “in fact it was probably invented when Lester B. Pearson gave his speech when he received the Nobel Peace Prize.”

While Canadians are known for having a peacekeeping tradition, Parker says “war” is a more appropriate description in most operations deemed as peacekeeping.

The government should “quit trying to make it seem what it is not,” Parker says. Rather, Canadian troops will effectively be at war if they go to Mali, where the situation is anything but peaceful, he says.

There were more than 100 casualties since the UN Operation MINUSMA started in 2013 in Mali.

Opposition leader Rona Ambrose accuses the Trudeau government of sending troops to dangerous places so that Canada gains back its seat at the UN Security Council. Trudeau did make promises during the October 2015 election campaign that his government would re-engage with the United Nations.

During Question Period last Friday, Defence Minister Harjit Sajjan said that “wherever we send our troops we’ll send them with the appropriate equipment, we’ll send them with the appropriate training,” and “we cannot just be sending our soldiers into harm’s way all the time – we need to start preventing conflict so we can reduce these things.”

Both Parker and Touré say they concur with the minister’s comment and that an approach that involves government officials on the terrain is better than a simple military operation.

Parker adds that the government needs to also think of how it will ensure the security of the troops.

But Master Warrant Officer Daniel Dospital says that troops have to do their jobs, regardless of the danger.

“It’s not my job to question the government; it’s my job to do my job,” he says.

Leave a Reply