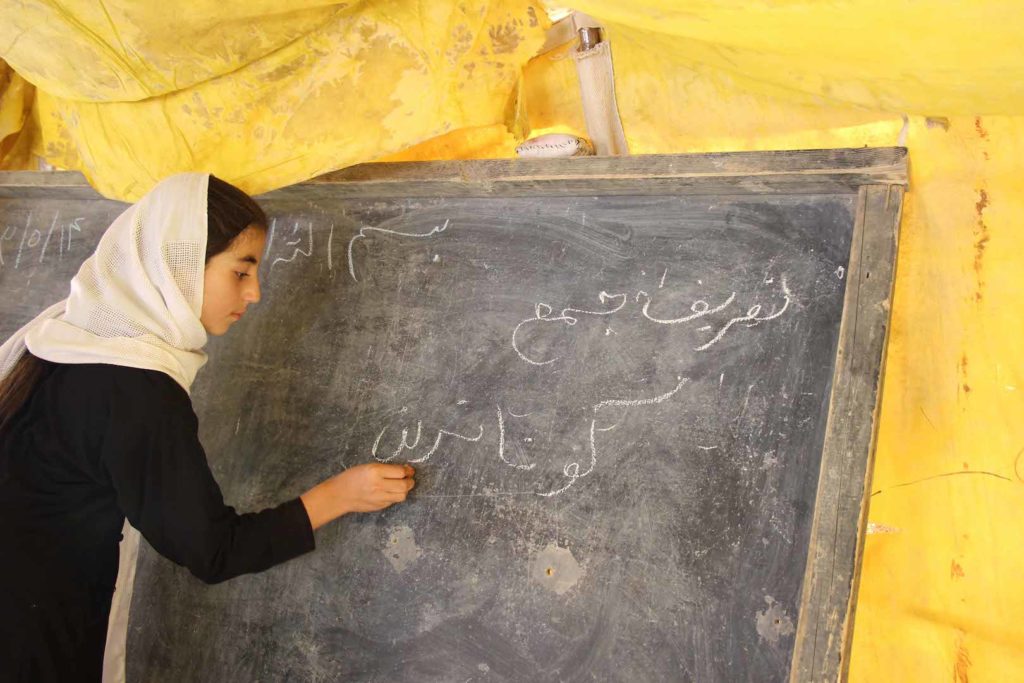

![]() Cover Photo: After weeks of fighting around the city of Kunduz, schooles reopened. May 2017. [Photo by Qais Azimy]

Cover Photo: After weeks of fighting around the city of Kunduz, schooles reopened. May 2017. [Photo by Qais Azimy]

The Western world poured billions of dollars into Afghanistan after the fall of the Taliban. One of the undisputed success stories of the war is said to be broadening freedoms of Afghanistan’s women. Under the Taliban, women were not allowed to go to school. Today more than 3.5 million girls are enrolled in school, and there are many programs promoting women’s rights and their freedoms. A significant number of Afghan women who had experienced the worst form of oppression started working as women’s rights activists soon after the fall of the Taliban, often supported by Western-funded NGOs. And with support from the international community, the Afghan women’s condition has improved significantly over the past 18 years.

The rise of an educated generation reached every aspect of social life – from political leaders to entrepreneurs. Millions of women have voted in national elections, most of them for the first time in their life. Of 249 parliamentary seats, the Afghan Constitution of 2004 guarantees a minimum of 68 seats, or over 25 per cent, for women. Women hold are ministers or deputy ministers, and a number of women serve as ambassadors. A new Ministry of Women’s Affairs was created as part of the government cabinet, with departments throughout the country at the provincial level.

Women’s sports programs in Afghanistan were a favourite of Western funding; Afghanistan has a strong women’s soccer team and women’s taekwondo team. Afghanistan now also has an Independent Human Rights Commission chaired by a well-known defender of women’s rights.

The extent of female engagement has reached the highest level of government in the country today. According to a recent Crisis Group report, “women now hold 27 per cent of civil service jobs.” In the 2004 Afghan presidential election, a female medical doctor ran against former president Hamid Karzai. Her name is Massouda Jalal; she was the only female candidate. While she didn’t win, she later served as Minister of Women’s Affairs for Afghanistan.

Another success story in Afghanistan is the establishment of freedom of speech and free media. Scholars say that this platform was invaluable in raising and supporting women’s rights; a common observation in research papers and interviews on this subject is that Afghan media are the voice of the voiceless. “Media absolutely empower women in Afghan society today, especially in public campaigning processes where it is more acceptable for men to participate, so it can be difficult for women to campaign. Media, especially in the 2005 elections, gave women the opportunity to campaign by giving them free access to the campaign,” said Peter Erben, a United Nations organizer of the Afghan election in 2005.

“Media help dissolve gender and ethnicity boundaries” said Roya Rahmani, a Canada-based activist promoting women’s rights in Afghanistan. She believes Afghan media are particularly useful in fostering education and knowledge.“For example, by seeing women speaking in the parliament or a woman as an anchor on T.V., this builds confidence of women’s talents that have been missing for a long period of time.”

Afghanistan was considered to have one of the freest media in the region among Iran, China and other central Asian countries. This is even more impressive considering how free media had been forbidden under the Taliban regime just 18 years ago. According to a 2016 Asia Foundation survey, Afghanistan had 174 radio stations, 83 private television stations and 22 state-owned provincial TV channels. Today these outlets effectively reach the country’s (estimated) population of 32.2 million.

Those achievements came at a high cost. The international community and the Afghans have paid in blood and treasure in Afghanistan for a prosperous and democratic country where women and human rights are respected. The U.S.-led war in Afghanistan is said to be “the longest war in American history, a conflict that killed more than 3,500 U.S. and NATO soldiers and cost the U.S. taxpayers nearly $900 billion and left thousands of Afghans dead and millions more displaced.”

With a power vacuum looming in the wake of the Taliban regime collapse in the last days of 2001, a group of prominent but underrepresented Afghans gathered in Bonn, Germany, to map out a path to forming a new national government. Coming mostly from the two main groups – the Northern Alliance who were fighting the Taliban in the north of the country, and the “Rome Group” representing exiled King Zahir Shah – they planned out a state where women wouldn’t be second-class citizens again. The Bonn Accords of December 2001 articulated a three-stage process of political transition.

Hamid Karzai was chosen as chairman of the Interim Administration (I.A.), which operated for six months, at which point the second phase began. The I.A.’s duties included running the state in the short term and preparing to reform the judicial sector and civil service. The government was to temporarily operate under the 1964 Constitution, which called for equality between men and women, with no distinction between them. In the newConstitution that followed, the right to free education up to the undergraduate level, irrespective of gender, was established.

Shahrazad Akbar, head of Afghanistan’s Independent Human Rights Commission, is one of the few Afghan women who studied in the post 9/11 era in “Western” post-secondary institutions; she attended Oxford University in England and Smith College in the U.S. Akbar believes a lot has been done for the empowerment of women around Afghanistan over the past 18 years. In her view, access to political participation, health, and education have all increased for women, but she sees that a lot of work remains in some critical areas like access to justice, an important aspect of women’s rights. “For the first 15 or 16 years, there was a lot of investment in our justice sector, but a lot of it was misguided and for the most part a waste,” said Akbar.

For her, the years of fighting and instability in the country also disrupted access to services and justice. Akbar argues that the police force is corrupt, inefficient and unqualified for their roles. She says they do not have the required training or education, a significant number of them may get into the police force because of political connections and nepotism. All of this “again complicates woman’s access to justice, because women cannot trust the police, the police have harassed women, female police officers are not present in many places,” says Akbar. “Conflict and the increasing Taliban influence in parts of the country have unfortunately reversed some positive achievements and woman’s access to education.”

In Fawzia Koofi’s journey to becoming a politician, she lived through civil war and the Taliban regime, rising to prominence after the collapse of Taliban rule. She was elected to the Afghan Parliament for the first time in 2005, and the following year she was elected deputy speaker of Parliament, the first woman in Afghanistan’s history to hold that position. Koofi says while the positive changes may seem significant compared to the Taliban’s dark ages, it still falls far behind the rest of the world. “We don’t have much freedom; right now Afghanistan is the worst country in the world to be a woman. So what freedom do we have?” asks Koofi.

For Koofi, the achievements of the past 18 years have not erased the consequences of a darker chapter. “There are horrible cases of violence against women. If you look at the literacy rate, Afghanistan has the lowest of literacy rates in the region,” Koofi said. “If you look at employment opportunities, if you look at access to economic resources, if you look at the social structures of Afghanistan, even the kinds of freedoms that human beings should actually enjoy within the social norms, Afghan women are deprived of it all.” Sadly, Koofi believes most of these new opportunities were limited to major cities or the capital, Kabul.

According to Human Rights Watch in 2017, “sixteen years after the U.S.-led military intervention in Afghanistan that ousted the Taliban, an estimated two-thirds of Afghan girls do not attend school.” Based on statistics from the Afghan government, 3.5 million children are out of school and 85 per cent of them are girls, According to Human Rights Watch report up to 80 per cent of Afghan women face forced marriages, many before the age of 16, and 87 per cent of Afghan women are illiterate. If the Taliban return to power this already grim prospect for women will plummet further. The Taliban refuse to give details on how they see women’s rights in the future, they simply describe the issue using religious contexts.

The Doha peace agreement was signed by Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, the co-founder of the Taliban movement in Afghanistan and their current political chief. In January 2020, Baradar spoke to Afghan journalist Najibullah Quraishi who was working on a documentary for PBS-FRONTLINE (Taliban Country). At the end of the interview, Quraishi asked Baradar an unexpected question on how they would treat women if they rule the country again. Baradar was vague: “There has been no change of Taliban mindset in this (women-empowering) regard. We accept all the rights that God has granted to women […] under the Islamic law, if they want to live and work, of course we will allow it.” “He was not happy with my question which is why I did not get a proper answer,” said Quraishi.

Even though Baradar said they have not changed, Quraishi thinks that Taliban could be more flexible now. “It’s good that [Taliban] leaders are now living in a country like Qatar, they can see some freedom of women there […] I think that might make them a bit open-minded and they could have a better look on women’s issues now,” said Quraishi, who often traveled with Taliban fighters in Afghanistan as a journalist. For him, when the Taliban say they accept women must live “under the Islamic law,” it is a demand that could require a change in the current Afghan constitution.

“The laws of Afghanistan are Islamic and even compared to some more progressive Islamic countries, it’s quite restrictive. Frankly, I can’t open a bank account for my son. Only his father can,” said Shahrazad Akbar, the head of Afghanistan’s Independent Human Rights Commission. As one of the few women who met the Taliban in Doha for peace talks, she is pro-Afghan engagement because she thinks “at least people [are] trying to put their narratives on the table.” Akbar is torn between hopes and fears for the future of women: “I’m exhausted like many Afghans … I’m also very concerned about the return to tyranny.” She thinks what the Taliban need to understand is that “their understanding, and their version of Islam is not necessarily acceptable to all.”