Integrating the community

Denise St-Pierre is in charge of the religious instruction of Catholic youth and adults in Baie-Comeau, Que., a town on the north shore of the St. Lawrence. The first time she met an African priest was about 15 years ago. Her initial reaction when she saw him? “Happy that he was coming,” she answered.

This is a common reaction among Quebec parishioners, according to Gaspé bishop Gaétan Proulx. He currently has eight priests from overseas working in his diocese. Twenty years ago, there were none. He said that churchgoers are usually welcoming to them, because they “know that if we didn’t have these priests, then there wouldn’t be a lot of people left to serve them.”

Serge Tidjani, who was born in Benin and who now works in Proulx’s diocese as a chancellor, echoed this sentiment. “Most people are grateful,” he said, adding that the majority of Quebeckers he met realized that migrant priests were leaving their home and loved ones as an act of service.

But the integration of these newcomers in the community is not always smooth. Cultural differences and misunderstanding are sometimes sources of tension, and some priest still report incidents of racism.

Subtle and not so subtle – racism in the parish

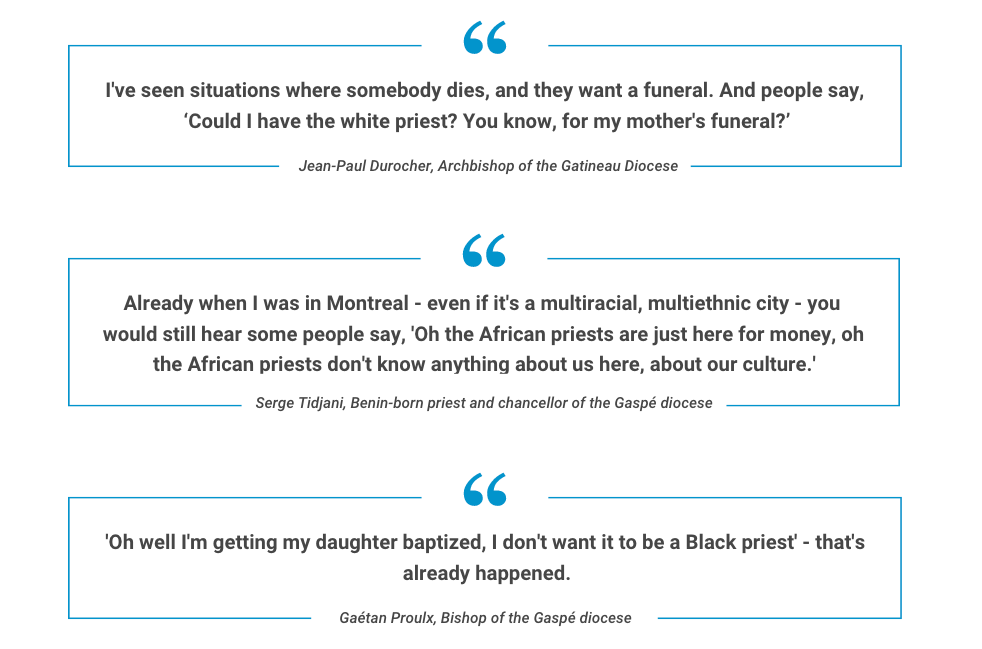

Quebec premier François Legault may have repeatedly denied that systemic racism exists in his province, but that hasn’t stopped bishops and priests from witnessing remarks aimed at foreign missionaries that were indisputably xenophobic or prejudiced.

“It’s not blatant, but it’s there,” said Paul André Durocher, Gatineau’s archbishop. For example, a member of his diocese asked him once why he was making the parish African.

Rimouski bishop Denis Grondin recalled similar conversations, saying some parishioners told him; “We don’t want them.”

Tidjani acknowledged that he had experienced racism, but maintained it didn’t reflect the majority of his interactions with Quebeckers. “It’s a minority, it’s really a minority,” he emphasized.

What helps is explaining to parishioners that all priests receive the same theological training regardless of where they’re from, said Proulx.

But sometimes, that’s not enough to foster acceptance.

What did you say?

A big obstacle to foreign-born priests being accepted by Canadian worshippers is their accents. “A lot of them tell me, ‘they speak French but we don’t understand them,’” said Claude Deschênes, pastoral representative for Sacré-Coeur, a small town in the Saguenay.

Some people in his parish told him that they would stop going to church if it continued that way.

“Here we speak Quebecker, you know,” said Deschênes laughingly. Whereas when Africans and South Americans clerics speak French, “their words are sometimes not said the same way as us,” he explained.

Proulx and Grondin also said parishioners came to them to complain about this issue.

Seniors, who make up the majority of churchgoers and who are more prone to hearing issues than younger adults, seem to have the hardest time understanding them.

Benin-born priest Serge Tidjani talks about how it was like for him to go through the experience of being misunderstood by his Quebec parishioners.

This especially happens in areas where immigration is low and people are not used to hearing different accents, said Jason West, president and vice-chancellor of the Newman Theological College. “It can create challenges and a certain resentment,” he noted.

In his role, West oversees an enculturation program for migrant priests working in Western Canada. Those in the program are specifically taught about the importance of speaking slowly and clearly, and are given resources to help them.

Not everyone cares if their priests speak differently than them though. “Someone told me, ‘we don’t understand him but he’s very nice’,” said Proulx, speaking of a priest that works in his diocese. They didn’t want him to leave because they really liked him.

Shorter mass, please

Another source of tension is the length of masses celebrated by some foreign-born priests. It is common for the ceremony to last a few hours in African or South American countries. “People will walk an hour or two to get to church on a Sunday morning and so they’re not going for a half hour celebration,” said Durocher. “They want something that’s worthwhile.”

It’s quite common, as a result, for priests there to repeat their sermons many times, coming at it from a different angle each time.

But this is in sharp contrast with mass celebrations in Canada, which usually don’t take more than 45 minutes.

“They give great long homily – it makes sense all of what they say – but it’s way too long for Quebeckers!,” said Deschênes.

Durocher remembers that his father was very frustrated the first time he attended a mass delivered by a Congolese priest in his parish. “He told me once, ‘Does he think we’re stupid? I understood the message the first time, he doesn’t have to repeat it three or four times!’,” the archbishop recalled.

It’s a harmless misunderstanding between two different cultures, but one that can nonetheless lead to friction.

Women belong in the church

A fear of being replaced

Rejection does not come just from community members. The Canadian clergy itself is not always happy to get new members.

Some local priests think they are being replaced on purpose because they’ve done something wrong, Proulx explained. They’re worried that it’s their fault that there aren’t any Canadian youth to take over the vacant jobs, he added.

Perhaps it’s like rubbing salt in the wound. “This church, who sent so many missionaries abroad, is now forced to turn to others for help. That’s not easy to accept,” said Tidjani.

They think that migrant priests are stealing their jobs and yet they “forget that they’ve maybe got the Canadian citizenship,” the Benin-born priest went on to say. “Just the fact that he’s from abroad shocks.”

Léonard Kapia and Nnaemeka Ali did not report facing racism when they spoke about their experiences living in their respective parishes.

To hear more about their experiences and to know what it’s like for foreign-born priests when they arrive here, see also “A day in the life – Calling Canada home”

Top photo © Émilie Warren