Cultural half-court

The crossroads of Chinese basketball

A flourishing economy, an emerging middle class and an athletic superpower – why China’s winning formula has failed its most popular sport and stripped the freedom of the millions who chase an impossible dream.By: Andrew Savory

Note: Due to the overlap of names, full first and last names have been used for clarity upon reference of Chinese individuals.

A six-year-old boy stumbled through the snow, the soles of his sneakers thick with slush. The sun had yet to rise as Yao Huafeng ran alongside his father, a farmer and former soldier. The daily routine began at 5 a.m. Together they darted between the alleyways of Huaibei, a small-town of two million located in the mountainous northern region of Anhui province.

“We had little money and I didn’t study well. My father told me I had to play basketball well to make a good future,” said Yao Huafeng. By the time he was 13, he but already knew he had little chance of passing the gaokao, China’s national college entrance exam.

The gaokao, or ‘high test’ is a historic tradition that was reintroduced in 1977 after the Cultural Revolution. That year, more than 5 million students wrote the standardized test in hopes of earning one of roughly 272,000 spots, according to Xinhua, China’s government news agency.

The test was designed to give students from rural areas a chance to compete with urban applicants for coveted spots at universities. Though admission rates have risen from below five per cent in 1977, provincial and municipal quotas ensure the test remains cut throat in nature. Police patrol neighbourhoods in advance of the exam to ensure all is quiet. Once testing is complete, a child’s path is clear.

Studies or sports.

Parents await their children following the gaokao examination in June 2016. Photo by: Thomas Snape, Flickr.

Yao Huafeng’s father lost his job in 1998 when Yao was 13. Both his sisters quit school to support the family. But his father had a different vision for his son: go to the provincial sports school in Hefei, Anhui’s capital. At 14, Yao Huafeng made one final morning journey with his father.

They left at dawn. He was unsure of what life at Anhui Sports School would be like. He had been guided by familial duty and knew difficult years lay ahead.

“It was my first time in a big city and I was filled with fear and excitement,” Yao Huafeng said. “My father told me, ‘Your mother and I will make the money we can to support you, but you have to look after us.’”

Every day for the next four years began at 5:45 a.m. with a run. Days ended at 9 p.m. Interspersed between was seven hours of training and practice. The only education offered was a mix of Chinese cultural theory and history. Some days, after a combination of laps up and down the stairs and jumping between tires, he’d miss class altogether, opting to crawl back to his room and sleep.

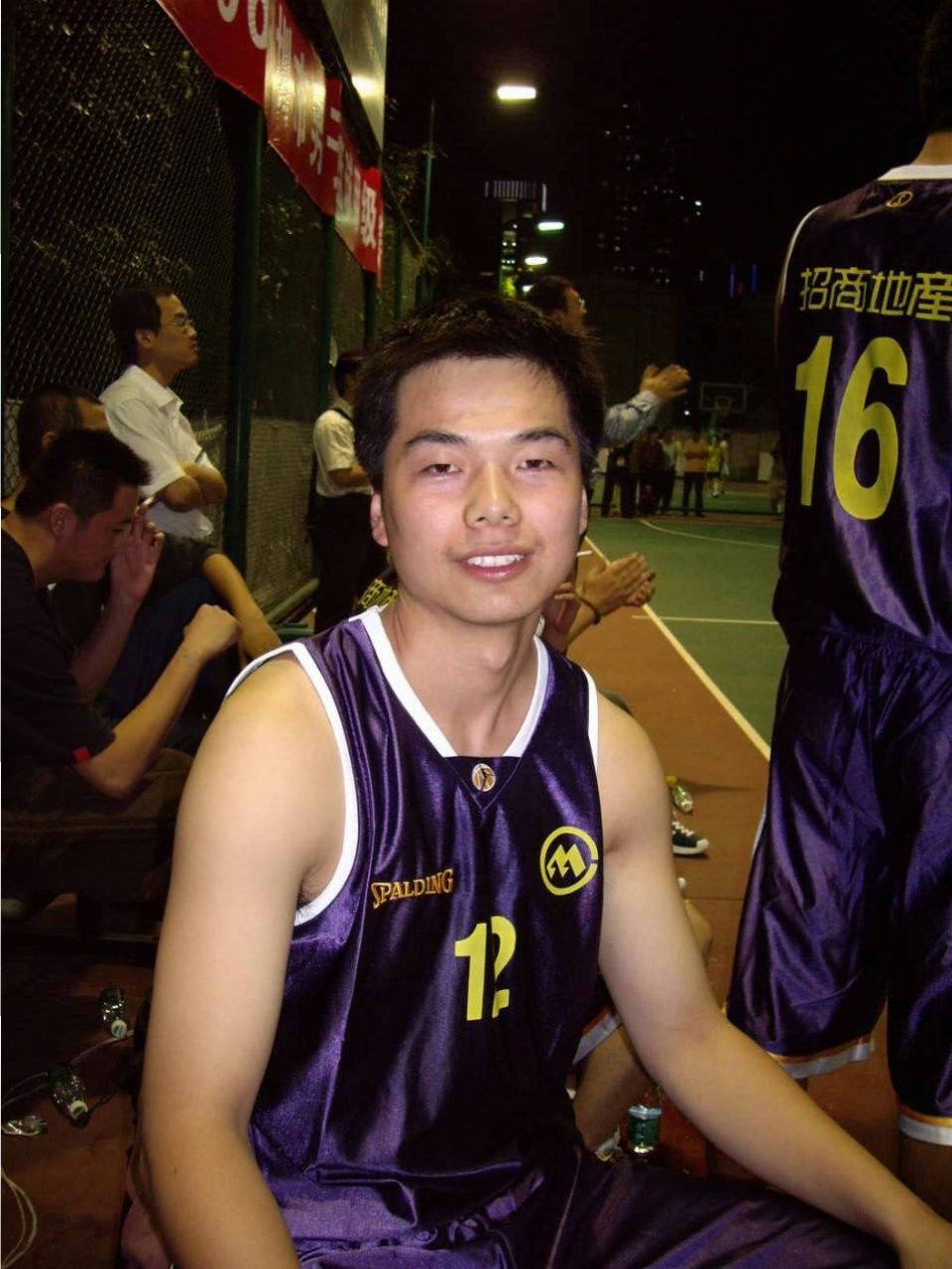

After arriving in Shenzhen, Yao Huafeng made a living by competing in corporate basketball leagues and tournaments. Photo courtesy of: Yao Huafeng.

It was difficult for Yao Huafeng to look further than a night’s rest into his future. After graduating at 18, basketball remained his only platform after leaving his education behind. He could chase a contract within the trenches of the Chinese Basketball Association (CBA), where lengthy contracts, dormitory living and excessive training is the norm, and individual freedom is not. Or he could pursue work in Guangdong province. With 350 yuan ($43 USD) to his name and his family’s struggles in mind, he left for Shenzhen, China’s city of the future.

Yao Huafeng’s experience was common. For many Chinese families, the sports school system offered a way to bypass financial difficulties. Athletes as young as six years old are introduced to intense training regimens that see anyone from a gymnast to a basketball player train up to eight hours a day, six days a week, under constant supervision. Education is limited.

The schools remained attractive following the announcement of then-communist party leader Deng Xiaoping’s new economic policy in 1978, which opened China’s doors to the West. Rural migrants flocked to areas like Shenzhen coined as “special economic zones” (SEZ). Cities of thousands became megalopolises of millions, occupied by an emerging middle class with new financial capabilities.

“Before this new wealth emerged, there were three reasons to send your kids to sports schools. The first is you were poor, the second is you cannot control your kids, and because the training is very strict, it’s like sending them to the army. The third is a few were really passionate about sports,” says Zhang Aihong, a professor of sport sociology at Beijing Sport University.

Zhang Aihong, professor of sport sociology at Beijing Sport University, in her office on campus at the the university. Photo by: Andrew Savory.

But the rise of China’s middle class has brought the slow demise of the sports school system. Parents are aware of the trials inflicted by the system – rigorous training, poor education and a lack of opportunity after one’s athletic career is over. According to government data, the number of sports schools has dropped from 3,687 in 1990 to 2,183 in 2016.

“It’s a Soviet system where each person is a tool within the machine. Athletes win gold medals while everyone else fuels the economy,” says Jiang Xueqin, an honorary principal at Chengdu Tonghui Primary School and a researcher for Harvard’s Global Education Innovation Initiative. “With the rise of the middle class and an urban elite, parents have begun looking for more education options for their children.”

China wants to use sports schools to manufacture athletes, but it hasn’t worked for its most popular sport. Yao Huafeng arrived in Shenzhen undereducated and underqualified for most jobs. Before finding work in the warehouse of an oil company, he could only afford to eat one fast food meal a day. Modern Chinese parents don’t want their children to endure a similar hardship. Like Yao Huafeng, players let down by the system wind up playing for corporate bosses against fellow drifters determined to salvage a pay cheque from the very sport they sacrificed their youth to play.

“I wanted to be the best, to go to the CBA. But my family had sacrificed too much for me. As a man, I had to take responsibility for them. So, I came to Shenzhen by myself. I came to fight for my life,” Yao Huafeng says.

China hasn’t been able to win any Olympic gold medals at basketball. The men’s team has never medalled, while the women’s team only medalled in 1984 and 1992. The irony is that the CBA claims to have a cohort of basketball players roughly equal to that of the entire United States. China’s desire to convert its mass into medals has opened the door to the NBA, which has begun taking matters into its own hands of fuelling the country’s basketball obsession. Unlike the NBA, a private multibillion dollar corporation, the CBA is made up of a murky division between both privately and publicly owned clubs.

Three avenues exist for Chinese players to pursue basketball. Teenagers can either join a sports school where communist ideology looms large, they can go to a public school and fight to avoid being vetted by academic thresholds and coaches bred from sports school traditions, or they can join state endorsed private academies that are backed by CBA and NBA money. Each system is trying to find its own way to overcome the communist distortion of a North American game.

Nanshan district is one of Shenzhen’s wealthiest neighbourhoods and is home to several sports facilities. Photo by: Andrew Savory.

Behind the glimmer and steel of China’s modern urban centres where the NBA has set up, the legacy of the old sports schools can still be seen and felt. Graduates of those schools now occupy positions of power within sports bureaus and continue to keep Chinese basketball anchored to the past while perpetuating the gap between the athletic and academic spheres.

Bureaus are facets of provincial governments that closely monitor sports schools’ players in hopes of finding the next prodigy that can bring provincial glory and preserve the jobs of bureaucrats for another term. In the absence of reform, Chinese children will continue to be forced to choose between basketball and academics.

*****

The price of admission: Chinese basketball players’ sacrifice

Yao Huafeng had come to Shenzhen during one of the largest short span population growths ever. The city swelled from the 30,000 fisherman and merchants that occupied its harbours in the 1970s to the diverse cluster of 11 million domestic Chinese and expatriates that now live within the glistening atmosphere of the 21st century megalopolis.

By coming to Shenzhen when he did, Yao Huafeng found himself on the right side of a historical migration that won’t happen again. Instead, a limited set of life prospects await today’s sports school graduates. Upon graduation, a player can be a coach at the school, destined to preach the same gruelling principles that were ingrained in them. Or they can attempt to enter the workforce following several years of regimented living and without a formal education.

Several CBA clubs have agreements with sports schools that sees school coaches provide their top players to the province’s CBA team when the player is a teenager. The incentive for coaches lies in the “development” fee that they pocket from the exchange. Coaches inside develop a reputation for supplying talent and soon become relied upon to continue fuelling the pipeline.

“Most of the time it’s the coach marketing the kid,” says Lukas Peng, director of scouting and analytics for the Guangzhou Long-Lions of the CBA. “You’ll hear, ‘Oh hey, this coach is trying to sell this kid. He’s 6’10 and he’s 14.’ They’ll send videos of them to keep you informed.”

A residential court outside the Guangzhou Long-Lion’s practice facility in Foshan, China. Photo by: Andrew Savory.

The whole process becomes a glorified auction that concludes with a teenager changing hands. Youth enter the depths of the CBA junior system, which functions as a feeder program. The CBA consists of 20 professional teams. Most are comprised of one senior and two junior teams. Teenagers are typically signed away from their school to a junior team between the ages of 12 to 17. Their signature solidifies what is usually a contract that can last a decade.

China announced that an estimated 300 million Chinese citizens play basketball. The statement prompted many to ask: where are they?

Yao Ming, China’s most successful player retired from the NBA in 2011. Despite standing 7-foot-6, height wasn’t Yao Ming’s only skillset. Yet his towering stature and illustrious career have perpetuated the status quo that height is the price of admission for those desperate to find his successor.

“GMs told me that to save your own ass, you don’t take a small kid. To the owner, if you’re going to spend money, you get a seven-footer,” Peng said. “If you take a kid who’s 6-foot-2, there’ll be questions like, ‘Why did I allow him to come?’”

*****

Basketball washed on the shores of Tianjin in 1896 when a group of YMCA missionaries brought a game invented by Dr. James Naismith with peach baskets and transported it to China in hopes of using it as a vehicle to promote Christianity.

The sport didn’t truly embed itself within Chinese society until nearly four decades later when basketball became interwoven with the military. China was in the midst of civil war between communist and nationalist forces in the 1930s when Mao led a ravaged Red Army on a near 6,000-mile trek across the mainland. Starvation had set in and to boost the army’s morale, Marshal He Long founded what came to be known as the “Fighting Army Team.” The sport was easily transportable. Between run-ins with nationalists, soldiers would bundle a basketball next to explosives in their packs, ready to play on their next stop after combat.

Basketball became a fixture not only among Mao’s troops, but within Mao’s vision of communist China. He saw the 1950s as an opportunity to restore China to its former glory and to shed a label that had grown pervasive throughout the last century – that China was the ‘sick man of Asia.’ He began purging western influences. Outposts, businesses and agencies disappeared. Basketball stayed.

Restoring national glory and rebuilding the national psyche was at the forefront of his agenda. He looked to his neighbors in the north for advice. To develop athletes, institutionalized sports schools had been devoted to stockpiling Olympians.

It paid off.

The Soviets finished second at their first Olympics in 1952. The message was clear to Mao. The Soviets had used sports as a platform to signal their emergence to the world not only as an athletic superpower, but as a global power. China could do so also.

“After the national government left, we didn’t have anything but a big division within our culture,” Zhang Aihong said. “The Soviets provided the theoretical foundation for our national sports system up until now. We learned everything by moving their sports school system to China.”

*****

A room of eyes fixated on a 14-year-old boy. It was 2006 and Junzu Qi was at the hospital for a test that measures the distance between the bones in his hand. On that day, his future height was predicted. It’s an inexact science, but it’s enough to invite the interest of provincial sports bureau officials and prospective professional coaches. A tape measure traced his hand before he placed it atop an x-ray. The next few moments determined whether Junzu Qi should pursue a professional basketball career in China.

The bone test serves as a rite of passage for China’s next generation of players. Just as the gaokao has long vetted students from consideration at China’s top universities, the x-ray is designed to project one’s eventual height. Over time, taller players tend to remain, while a blind eye is turned to smaller players.

“It’s a process that all players at the sports school will go through at some certain age,” Junzu Qi says. “The problem is just the old culture. The coach has too many players to pick from.”

The scan of the bones in Junzu Qi’s hand predicted that his future height would be to his detriment. He would be too short to play game. He left his hometown of Benxi for the Shenyang Sports School in Liaoning province shortly thereafter. Liaoning is the breeding ground of Chinese basketball. Estimates vary, but various CBA players and managers suggest that as much as 60 to 70 per cent of Chinese professional basketball players come from Liaoning, a province known for its colder climate, tough demeanour, and most importantly, taller humans. For centuries the people of Liaoning have been known as warriors, hunters and athletes.

*****

Downtown Shenyang, the capital of Liaoning province and one of the many industrial, coal-burning cities in China’s northeastern corner. Photo by: Andrew Savory.

One day during practice Junzu Qi soared for the ball, collected it in midair, only to collide with another player. There was a click, followed by a snap in his ankle. He knew immediately – his time at the sports school was over.

“I looked at my parents and I knew that I would never be tall. When coaches know you’re injured and you won’t be able to be back to that level again, and also that you won’t be tall, they make changes and switch their mind,” Junzu Qi says.

Registering its players with the provincial sports bureau has allowed Liaoning to maintain basketball dominance. Once registered, players are positioned at the base of a siphon intended to help Liaoning’s professional club gets first pick of the province’s best players.

Before breaking his ankle, Junzu Qi was buried in this system. Upon admittance, he and his peers were registered with the Liaoning sports bureau. After being checked in, he was escorted to his room and met his three roommates.

Sports schools’ top players are viewed as invaluable commodities. Once registered, players are tied in service to bureaucrats, who in turn prioritize the state’s interests and success at provincial competition over players’ individual freedom. Teams from rival provinces will offer anywhere from hundreds of thousands to millions of yuan for elite talent. The better the player, the less likely the government is to allow them out of its grasp.

“That’s the issue. You can’t go anywhere,” said Xiang Cheng, vice president of the Liaoning Flying Leopards of the CBA.

Junzu Qi, seen crouching third in from the right on the bottom row, in his freshman year at Benxi City High School. Photo courtesy of: Junzu Qi.

Junzu Qi transferred to Benxi City High School two months after breaking his ankle, where he learned that even in the public school system, mastery of basketball was a matter of school pride. One game, Junzu Qi’s team found itself ahead by 15 points. As the buzzer neared, he set his sights on eclipsing the school’s scoring record. But his coach had a rule: they weren’t allowed to beat an opponent by more than 15 points.

Junzu Qi pushed the lead above 15 points. His coach told him to stop. He didn’t. Junzu Qi found himself at the free throw line on the next possession. His coach ordered him to the sideline in between his two shots.

“He slapped me in front of our school’s principal. He had to show my principal that he had power – that he’s leading the team and that everyone is scared and listening to him, which is pretty normal,” Junzu said. “It’s all about keeping face in China.”

But the public system offered something more than basketball.

Gong Li was Junzu Qi’s high school English teacher. She noticed his struggle to catch up academically while balancing basketball. Practice in the evenings would end around 10 p.m. After practice, Junzu Qi and his peers would go to a study centre to review class notes before returning home at midnight.

Science had said that Junzu Qi would be too short to play. His dream of playing professionally wouldn’t happen. Now, his studies had fallen behind. When the game left, there’d be nothing for him. If he wanted to leave Benxi, it would have to be through school, Gong Li warned.

That message resonated with Junzu Qi. He shifted his focus towards the gaokao and earned a spot at Shenzhen University.

Shenzhen University in the summer of 2017. Photo by: Andrew Savory.

There he met Joel Haines, an English tutor from St. John’s, N.L., who took an unofficial after school basketball program and turned it into a cross-country enterprise. Haines hired Junzu Qi as an assistant basketball coach at Five-Star Sports when he was an undergraduate student.

Five-Star’s goal isn’t to produce professional players. It’s a business that uses the attraction of English-language instruction in conjunction with physical recreation to garner parents’ interest.

The company limits recreational basketball classes to once a week so as not to deter parents or jeopardize their childrens’ studies. The program has branches in Guangzhou, Chengdu and Shenzhen and has trained more than 3,000 kids. Its growth has invited the interest of local coaches, who according to Junzu Qi, dangle entrance and education certificates at the city’s best schools to gain control of a player prior to feeding him into the professional system. Such offers often come with a price tag.

Five-Star’s best players have been contacted by local high school coaches, who assure that players won’t need to attend class and will still receive high school and university certificates just for being on the team – but only if the player pays the coach, Junzu Qi says.

A young boy crouches near the three-point line on Five-Star Sports’ courts in Shenzhen, Guangdong, China. Photo by: Andrew Savory.

Junzu Qi, now chief growth officer at the company, acknowledges that Five-Star isn’t going to change the landscape of Chinese basketball and that the company caters to wealthier families. Despite the country’s economic climb, China remains crippled by rampant income inequality between its urban hubs and massive rural population. The avenue offered by Five-Star only exists for select families. BMWs and Tesla charging stations encircle the courts under the shadow of Nanshan’s high-rises. On a nightly basis parents gather to watch their kids receive English instruction from a foreign coach and a Chinese assistant coach.

As Harvard researcher Jiang Xueqin explains, competitive sports aren’t an avenue that China’s public school system adequately provides. The system prioritizes academics and most schools lack anything more than a recreational team, leaving private schools and programs like Five-Star as some of the few outlets for organized competition.

Even in China’s capital of Beijing, a city of nearly 22 million people, only an estimated 200 basketball teams exist out of 1800 combined elementary, middle and high schools, according to Ma Ming, deputy secretary general of the Beijing Basketball Association.

“Most parents want their kids to be successful in basketball and any sport, but most parents also want their kid to go to university,” Ma Ming says. “If you play ball, you have no future. You must master your studies and pass the examination.”

A foreign Five-Star coach provides English instruction to young Chinese basketball players attending an evening basketball class. Photo by: Andrew Savory.

What Five-Star offers is an alternative to the pitfalls of a development system that fails to entertain the notion of a student-athlete. Junzu Qi says he’s begun a habit of sitting down with parents and encouraging them to send their children out of China if they want to play basketball.

“In Canada you would never say: ‘Okay, this is Monday, you cannot play basketball.’ In China, you have to make a decision between if you do sports, or if you do education. There’s no middle gap where you can do both,” Junzu Qi says.

“I push kids to leave early. The earlier they get there, the more chances they have. If you get there from elementary school, their whole story changes.”

*****

The legacy of sports schools’ old guard

Young gymnasts practice at the Shanghai Sports Institute in early August 2017. Photo by: Andrew Savory.

Six toes point towards the ceiling. Heels arch. Three sets of ankles press tightly against one another. Two ponytails slink to the floor. Slight wrinkles in the mat begin to form under the pressure of bodies in perfect formation. Three girls, no older than six or seven, hold their stance upside down. Their handstands are unwavering. Five minutes pass before they level on their feet.

Quick breath. Repeat.

Their back muscles have already begun to show. Behind them, a shirtless boy admires their poise while others await their turn at the Shanghai Sports Institute.

This is the next generation of Chinese Olympians.

“A colleague of mine works at another school like this. He told me that the girls there can go for a half-hour. They’d fall asleep upside down,” whispered Gavin Pratt, a performance manager at the institute.

An exterior wall bordering the Shanghai Sports Institute’s entrance. Photo by: Andrew Savory.

Dance routines are practiced in the center of the room by some of the young gymnasts. Photographs of the routines aren’t allowed due to suspicion of stealing ideas. A girl on the left side of the room paces on a treadmill in front of a horizontal mirror. Her reflection casts the image of a child walking steadily, wires dangling near her wrists, transmitting her heart rate.

“Basketball players mostly need joint therapy from repetitive stress, whereas gymnasts suffer from soft tissue damage. Both are caused by overexertion. They normally train for six to eight hours a day,” Pratt says.

The facility – Meilong as it’s referred to, named after the suburb where its based, is home to some of the best athletes in China. Gymnastics, trampoline and hand ball are its specialties. The sports school is also home to the Shanghai Sharks of the CBA. Approximately 300 full-time students live in the dormitories. Some are Olympic hopefuls, some have already been crowned world champions, others have been dropped off and forgotten by their parents, Pratt said.

Yao Ming, the greatest of all Chinese players, once trained here as a member of the Sharks.

The Shanghai Sharks’ junior team practices behind a curtain at the Sharks’ practice facility within the Shanghai Sports Institute. Photo by: Andrew Savory.

The Soviet inherited system has had fantastic results in terms of assuring an impressive medal count. After sitting out the 1956-1978 Olympics, China saw its medal count slowly rise at the Summer Games throughout the 1980s and 90s, culminating with the most gold medals of any country at the 2008 Games in Beijing. Reuters reported in 2016 that over 95 per cent of China’s 639 Olympians were sports school students or alumni. But that number has started to drop. China recorded 91 medals in London in 2012, and 70 in Rio de Janeiro in 2016. Most of China’s victories come in individual sports like diving, gymnastics and weightlifting, as well as “small ball” sports like ping pong and badminton.

The playing environment in these sports never changes, whether it be the height of a bar, the length of a table, the weight lifted, or the same opponent for the duration of a match. K. Anders Ericsson once theorized that it took 10,000 hours of practice to become an expert at a chosen discipline. Much debate surrounds the theory’s validity, but one thing is certain – Chinese professional athletes born from the sports school system greatly exceed this mark.

But the formula hasn’t worked for team sports like basketball and soccer – with the exception of volleyball, where the women’s team ranks first in the world and the men’s team 20th.

These sports—big ball sports—require split-second decision making and teamwork to adapt to the up-tempo nature of the game. Players never face the same situation twice, whether it be in the form of a defender or teammate. Intuition is required to adapt to constant play calling. The regimen of fierce drilling has left Chinese basketball players lacking the intuition necessary to succeed at the game and susceptible to wear.

“Chinese athletes play very one-paced because they’re always saving themselves for the four-hour session that comes next. ‘If this is the first 30 minutes of a session, I need to be sure that I’m still here three hours from now,’ said Brentan Parsons, an Australian strength and conditioning coach at the Shanghai Sports Institute.

*****

Ma Jian became the first Chinese-born player to play NCAA-DI basketball in 1993. Five years earlier he was playing for the junior national team.

A group of American coaches had been invited by the CBA in 1988 to host a clinic for Chinese coaches.

Ma Jian had worked towards this moment. He’d been fascinated with basketball ever since watching his first NBA game on a black and white television in the 1980s. The energetic play, the emotiveness of the players – the freedom one could have while on court.

He wanted to leave for America. Ma Jian’s physical style of play caught the attention of his coaches. The team had been instructed to run drills at 80 per cent, but Ma Jian saw the exercise differently.

“I dunked on one of my teammates,” he recalled. “I did everything with energy. I knew that it was an opportunity. If I got recruited, you never know.”

The dunk caught the attention of Jim Harrick, who asked Ma Jian a simple question: do you want to go to UCLA?

“Sure, where’s UCLA?” Ma Jian said, unsure of just how difficult leaving China would be. He wrote letters to government officials for three years, pleading his case. The response was always the same. No.

Ma Jian was Chinese basketball’s greatest hope in the early 1990s. He tried to argue that he should be allowed to leave on the merits of North America having the best quality of basketball in the world. If he wanted to improve, he had to go. For doing so, they punished him. If Ma Jian couldn’t succeed within China’s system, then he shouldn’t be allowed to succeed at all.

“I’m not a party member, I was just a 20-year-old boy that wanted to play basketball,” Ma Jian says.

The national team travelled to the Philippines in 1991 for a series of exhibition games. One morning, Ma Jian snuck away to write the SAT required for admission to UCLA. But his English had hardly improved since he met Harrick. He took the test and failed.

It took four years for his request to go to America to be approved. By then it was 1992 and the Barcelona Summer Olympics were about to begin. Ma Jian was on China’s team at those Olympics. By then, he was viewed as a defector. The Chinese lost all seven of their games and Ma Jian, the only player to receive formal consideration from American coaches, was largely confined to the bench for political reasons by Jiang Xingquan, a former player and coach for Liaoning. “They think that I embarrassed them,” Ma Jian now says.

In America, Ma Jian was somewhat of a trailblazer. In China, he was an outcast. By 1996 he had played two years at the University of Utah and was still one of China’s best players, but he was given no place on the Olympic team. “That’s when I thought, ‘Oh, fuck off.’ I was really pissed,” Ma Jian says.

“I give very honest opinion about my basketball knowledge because I learned it from the world. I learned from my education. I have my own opinion and I’m not a politician,” Ma Jian said. “I can straight tell them, ‘You’re shitty, you’re not good enough. Look, you’re missing all the details.”

Ma Jian wasn’t the only player shunned by the Chinese establishment for playing in America. Wang Zhizhi was similarly shunned in the early 2000s after attending summer camp with the NBA’s Dallas Mavericks rather than returning to China for a national competition. Wang Zhizhi was subsequently barred from the national team, as reported by Newsweek’s Brook Larmer in his 2005 book Operation Yao Ming.

*****

A performance by young boys and girls during an intermission at a game between Anhui Wenyi and the Beijing East Bucks. Photo by: Andrew Savory.

Twenty seconds remain and the sound of thousands of plastic boomsticks bursting under the feet of a hometown crowd anxious to leave are turning Anhui Wenyi’s arena into an echo chamber.

The game was over by halftime. Russ Smith, an American, scored 21 points in the first quarter while teammate Bernard James sat bored underneath the basket with a pair of headphones on. Prior to the game, a group of kids no older than five had taken to the court to perform a series of ballhandling tricks that concluded with a toddler balancing basketballs in either hand while doing the splits.

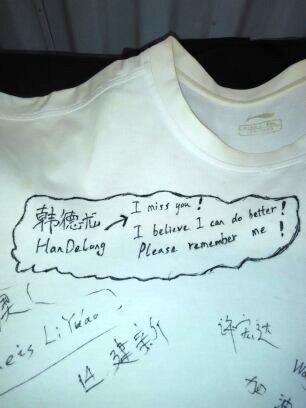

“This is the burial ground for most Chinese players,” says Bob Pierce, a China-based scout for the Miami Heat of the NBA. Yet this isn’t a scouting trip. Pierce wants to know what happened to Han Delong, the boy that gave him his t-shirt the first time they said goodbye in 2008 when Han Delong was 13 and a member of Xin Sheng Wei, a team Pierce coached for footwear giant Li-Ning.

Pierce, front center in red, with the Xin Sheng Wei junior team where Han Delong can be seen in the back row directly behind Pierce, seven in from the left. Also seen is the shirt that Han Delong and the rest of the Xin Sheng Wei junior team signed on the day of Pierce’s departure from the team. Photos courtesy of: Bob Pierce.

Han Delong scored a modest eight points and showed flashes of the quick guard that had made him a player to watch in China’s junior system, at one point even trying to dunk over a taller opponent, only to be blocked on his way to the rim.

Pierce and another one of Han Delong’s former teammates with Xin Sheng Wei, Xi “Tiger” Yuxing, await his arrival at a local restaurant close to Anhui Wenyi’s stadium.

Tonight’s the first time Pierce has seen Han Delong in nearly two years. A plate of boiled pig ears and a skillet of pig brain fill the distance between them. Han Delong arrives and takes a seat at the table. He’s 6-foot-5 with a slender build. His navy hoodie hangs loosely from his shoulders. Tiger points across the table at Han, gesturing at the cell phone in his hands. “Where’d you get that?” Tiger asks. Team policy requires Chinese players to hand in their phones the night before a game. Han Delong smiles. He had two.

This isn’t where Han Delong expected to be at 22 – a member of Anhui Wenyi, a team in the National Basketball League (NBL), a second-tier professional league in China. He had once been a promising member of China’s national junior team and was supposed to be in the CBA as a member of the Bayi Rockets. But Han Delong’s trajectory was broken by a team that refuses to change. Spat out of the professional system that he seemed destined to ascend, Han Delong is confined by an under the table agreement to the NBL, a league that American journeyman use as a training ground while Chinese players wait out the rest of their careers.

In his teens Han Delong played against now current NBA players at international tournaments. He never believed that he could make the NBA, but he takes pride in the knowledge that at one point in his life, he could at least compete against legitimate NBA prospects.

Bayi was Han Delong’s former team. Its name, Bayi, pays direct homage to the anniversary of the People’s Liberation Army on August 1, 1927. The Rockets are the Chinese army’s team. They enjoyed dominance when the CBA commenced in 1995, winning seven of the first eight championships. As Li Ke, a former player for the Rockets in the early 2000s, remembered, players would train three times a day, six days a week and would dress in uniform once a week for military theory, designed to “bring us together.”

“Bayi’s culture isn’t just something built in three or four years. It was built over generations,” Li Ke said. “When you’re on Bayi, you represent China, you don’t represent anything else and China always comes first.”

To wear Bayi’s crest was to wear China on your sleeve.

Li Ke, left, and Wang Zhizhi, right, stand in uniform holding the CBA championship trophy after the Bayi Rockets’ title in 2007.

But a steady influx of foreign import players from outside of China has tilted the scales in favour of the 19 other CBA teams that have capitalized on the right to have as many as two international players on their roster. The lone exception to the rule is Bayi – the sole club comprised of only Chinese-born players. Since their 2007 championship, the Rockets have only finished with a winning record twice.

Despite its regression, Bayi refuses to abandon its ideals.

Han Delong’s development was snuffed out by an organizational power structure that’s compounded within the confines of a military institution. He joined Bayi in 2008, inspired by the Rockets’ allure as the titans of Chinese basketball. But Han Delong found anything but inspiration as a member of Bayi. It took him six years to rise to the surface of the Rockets’ senior team. Once there, he played sparingly. Suspected nepotism began to circulate the team as head coach Adiljan Suleyman’s son received more playing time at his position. Han Delong wanted to leave.

Switching professional basketball teams in China is difficult. It can be done, but rarely on players’ terms. With no players’ union or free agent system, players can’t opt out of contracts early. Most players sign contracts dating back to when they were teenagers, with terms lasting upwards of a decade. In exchange for subsidized accommodation, food and a small monthly stipend, fringe players forego bargaining power when disputes arise. Players are investments and several clubs won’t allow it if a talented player wants to leave.

“I don’t want you to go outside the club because if I let you go, I’ll end up playing against you later on,” Xiang Cheng says of China’s lack of a free agent system. “It kind of hurts the player, but we have no choice.”

Han Delong had two years remaining on his contract when he left Bayi. He stayed in Beijing to train. “Some teams tried to connect with me, but I couldn’t go,” he says.

Han Delong’s tight-lipped when asked about the two years between playing for Bayi in 2014-15 and starting his NBL career in Anhui in 2017. “Little by little, it felt like I was losing favour,” he says. Han Delong had been blackballed by the system. If he didn’t want to play for Bayi, then he wouldn’t play for anyone.

“Usually once your contracts up you can go, but for a lot of guys it never ends,” Pierce explains. “They’re kind of in limbo.”

Pierce met with Han Delong early in his time spent training in Beijing after leaving Bayi and before he went to Anhui. Photo courtesy of: Bob Pierce.

Han Delong had reached out to former national team coach Gong Luming for help regarding his disagreement with Bayi. Guanxi has no direct translation, but it’s generally used to reference the tight-knit relationships born from close personal and professional connections. Han Delong wouldn’t have been able to leave Bayi without the help of Gong Luming, now a senior executive with Anhui Wenyi.

Gong Luming used his contacts inside Bayi to help negotiate for Han Delong’s freedom from the team so that he could play in the NBL, so long as he stayed away from the CBA entirely.

Few CBA players re-emerge from the NBL after falling to the second-tier league. Though Han Delong is determined to try, he knows the odds are against him. He was given no choice but to leave by speaking out against Bayi. For doing so, he lost two years during a formative period of his career. Now as a member of Anhui, all he can do is hope to make up for time lost at the hands of Chinese basketball’s rigid old guard.

“The first time I left Bayi I felt free. For once, no one was in charge of me. I had a chance to become an adult,” Han Delong says. “Every day was hard. It made me grow up. I love basketball and I have faith – I need to hold on to that. I have suffered through a lot, I’m not willing to give up.”

*****

Struggling for reform under the government’s shadow

He stands on the outskirts of the huddle, his neck bent, his shoulders slumped. A red and white towel soaks the sweat gleaming across his collarbone.

Zheng Zhun’s arms dangle at his sides, gangly and undefined.

He steps to the free throw line, expressionless. He grips the ball between his hands, looks downwards, before tilting his chin up, raising his arms, and releasing the ball with a flick of his wrist. One fluid motion, twice repeated. Two for two.

“He’s your traditional Chinese big man – a smooth shooter who hits like 90 per cent from the free throw line. But he’s not very good,” says Lukas Peng, Guangzhou’s director of scouting, as he leans over a balcony overlooking the Guangzhou Long-Lions’ practice court in July 2017.

“He’s a 7-foot-1 center who hates basketball.”

No smile, no fist-pump. Zheng Zhun turns and runs back on defence, numbed by the monotony of life as a Chinese professional basketball player.

Zheng Zhun is the type of player that Chinese scouts clamour for. His name began circulating internet message boards in 2006 when word spread that a 7-foot tall 14-year-old with rail thin limbs caught the attention of NBA player Dwight Howard at an Adidas camp in China.

Height can be projected, quantified, and as Yao Ming demonstrated – dominant. Zheng Zhun’s been the opposite. He is one of many Chinese big men that have been prioritized because of their height – despite an evident lack of coordination, body mass and passion. Contrary to what doctors and coaches had hoped of Zheng Zhun when they tested for his height, his stature has not translated to skill. He entered the professional system when he was 12 and has been a professional for more than a decade. Basketball is all that he knows.

Mike Schierhorn, back middle in white, provides direction to a team of players brought together to help Guangzhou gauge its level of talent during the offseason. Photo by: Andrew Savory.

Zheng Zhun and the Long-Lions are playing a team of American ringers – journeymen with resumes spanning varying levels of collegiate and university basketball. They’ve been brought together by Mike Schierhorn, known to many in China as “China Mike.” Schierhorn has a reputation for assembling teams of western ballers to come to China to compete in “wild ball” tournaments. The name’s derived from the quick payout that can be earned and also the scarce insurance coverage players receive. The stakes can be high. Win, or go home. Lose, no pay cheque.

There are many here like Zheng Zhun, a cohort of players who loved the game once, but grew sick of what it had denied them – an education, daily free time and agency. Players like Zheng Zhun have no joy for basketball anymore, Lukas Peng says, but they have no other alternative but to keep playing.

“Where would they go?” Lukas Peng says. “They can’t go out, it’s like jail.”

Lukas Peng has known Zheng Zhun long enough to know that he hates his job. Hates the game and what it represents. The only reason he continues to play is because he can’t think of another way to earn the money he does from the court.

As Lukas Peng recounts: “We walked by the parking attendant and he told me he would rather that job. I asked why because it’s not a great job and he said, ‘Yeah, but at least I get to sit.’”

Zheng Zhun and the rest of the Long-Lions are the leftovers of the former Shaanxi Kylins team that was purchased and later relocated to Guangzhou. Many of Shaanxi’s best senior and junior team players had been sold off by the time the team moved, said Xu Song, general manager of the Long-Lions. It’s now Lukas Peng’s task to restock the Long-Lions’ depleted junior system with talented teenagers.

CBA teams’ junior programs typically range between 20 to 40 players. When this number is adjusted to include the junior programs of the NBL and other lower leagues, the result is a foundation of between 2,500 and 3,000 potential professional players – far from the 546,428 American high schoolers that supply the 18,684 university students scattered across NCAA Division I, II and III campuses, according to 2017 NCAA data.

Scouts like Lukas Peng and government officials alike know how illusory the CBA’s statistic of 300 million supposed players truly is.

“There’s no official record here. I can say that our registration system for basketball players isn’t good. So many people want to play basketball, they want to register, but we don’t have a system,” says Li Fang, the deputy secretary of the Guangzhou Basketball Association.

The mass infrequency of organized basketball in the school system has created a breeding ground for corruption and exploitative recruiting tactics. Good, young players are hard to come by. Teams resort to extreme measures to convince a child, coach and parents that their team is the right choice.

Different professional teams use different methods, such as offering residency in upper crust cities like Beijing, greater payouts for the coach that trained the child, and in some instances, university education certificates, despite the player not likely attending university, Peng said.

Citizenship in cities like Beijing is especially enticing because the gaokao has a regional prejudice. The entrance score required to get into top schools like Peking or Tsinghua—China’s equivalent of Harvard and Yale—is lower for students from Beijing compared to students from other provinces.

“If you’re from a small village, you can get a Beijing ID. So, when you have a kid, your kid is from Beijing and they can go to school in Beijing. It’s hard to get, unless you work for a government agency,” Lukas Peng says. “Stuff like that matters when you recruit. Money matters.”

A tour is given on the campus of Tsinghua University in the summer of 2017. Despite being years away from vying for admission, the prospect of going to a prestigious university is enough to lead students to study years in advance of competing for limited spots at the school. Photo by: Andrew Savory

The team has begun using a new bartering chip to entice parents to let their children join Guangzhou’s farm system – schooling.

But, according to the Long Lions’ general manager, once a teenager signs a CBA contract, the closest semblance to an education he’ll receive is diluted mathematics or history on site at the playing facility.

Youth team players like Song Shuai, a shooting guard on Guangzhou’s junior team, wish they didn’t have to leave their education behind just to go professional.

Song Shuai began his career with Dongguan’s junior team when he was 13. The dorm rooms were tight with bunkbeds taking up most of the room’s walking area. Song joined Guangzhou when he was 15 and was paid 800 yuan monthly, equivalent to $116 USD. Six years later in August 2017, he was earning 2500 yuan monthly ($363 USD).

“We practice two to three times a day, everyday. It’s normal. No games, just practice. Basic training everyday. I have no money to spend to go out,” Song Shuai says. “It’s very little. I can’t save up at all. It’s too little to send back home. So, I choose to stay in my room.”

Players like Song Shuai are subsistent on basketball. The longer they remain in the professional system, the more the sport becomes their means to an end that will likely never come. “I wouldn’t ever quit basketball to go back to school, but I do wish that I could do both because I feel like I’m missing out on a lot of knowledge,” he says.

One of the universal fears among Chinese professional basketball players is what they’ll do after retiring. To answer this anxiety, Xu Song’s tried to offer a way out for those that want it. The Long-Lions helped a community university establish a basketball team and in return, the university allows players to study at the school, Xu Song said.

Xu Song hopes that schooling and a greater reliance on drafting Chinese University Basketball Association (CUBA) players from the CBA Draft will help bring reform to the CBA. Photo by: Andrew Savory.

The Long-Lions are the latest rebels within an association with a history of silencing reform or protest. To create change, Guangzhou must fight a system built to uphold bureaucracy at the expense of sacrificing players’ education and wellbeing. Guangzhou wants to create positive change, but they must also play by the rules.

“We are already one step ahead of China, but we face problems because we can’t solve the whole system that China still largely follows,” Xu Song says.

Despite their efforts, the Long-Lions’ domestic pool of players isn’t good enough to rival government influenced powerhouses like Liaoning and Shandong, which have a firm grip on their province’s top players. In the past, Xu Song said Guangzhou was comprised entirely of sports school graduates, but since the inaugural CBA Draft in 2015, they’ve been cultivating talent from the Chinese University Basketball Association (CUBA).

“We attract parents by allowing school and university. Some clubs just invest a lot of money in players. Some are very traditional like Liaoning and Shandong – they can register kids when they’re very young so that they belong to the province,” Xu Song said.

Like many international professional basketball leagues, the CBA places a cap on how many “import” players a team can have. The allure of import players is evident. To a Chinese owner, two high-scoring Americans can lead a team from relative obscurity to national prestige in the matter of a season. There is one exception, of course. The Bayi Rockets. The Rockets don’t have any import players. When opposing teams face the Rockets, import players can only play four quarters collectively across a game that only spans four quarters in the first place.

The relationship between import players and Chinese basketball’s development is a test of patience for many CBA teams. Adding a high-scoring American can vault a team from the bottom of the standings to the top in a season’s time. Developing a foundation of Chinese talent takes years, and as Xu Song notes, the appeal of the playoffs, increased ticket sales and honour often supersedes the several years needed to establish a junior system of Chinese talent. The highest scoring Chinese player in the CBA last season, two-time league MVP Ding Yanyuhang, only finished 20th in league scoring. Import players occupied spots one through 19.

Photos from inside and outside of the Guangzhou Long-Lions’ practice facility in Foshan, Guangdong, China. Photos by: Andrew Savory.

Players, coaches and managers within Chinese basketball are trying to change, but the path ahead won’t be easy. Families are wise to the consequences of attending a sports school or signing a professional basketball contract. Parents want their children to receive an education.

The Long-Lions don’t have a solution for the myriad ways in which the divide between the academic and athletic spheres has rendered the growth of Chinese basketball stagnant – they are still bound by the constraints of a largely government-controlled system. But giving players the chance to stay in school until they’re 16 is a start.

“Kids don’t want to play in the CBA. It’s like the new trend,” Lukas Peng says. “If you go to the CBA, you don’t have an education, you don’t really get to play, it’s somewhat corrupt if you don’t know somebody – that’s what they think.”

Xu Song believes that in order for Chinese basketball to improve, change must come from within. Photo by: Andrew Savory.

For every sign of progress, there is the weight of tradition. Liaoning remains responsible for the predominant production of China’s players. The province’s CBA team, the Flying Leopards, are perennial contenders and have no interest in drafting a Chinese university player. The team has yet to select a player in each of the CBA Draft’s three years running.

The choice is made partially on the grounds that they don’t believe university players are good enough to be on the team, but also because they’ve already invested nearly a decade in incubating a crop of teenagers within their junior system. Historically, Liaoning’s best players aren’t allowed to leave. They’re indebted to the state after a decade’s worth of free accommodation and basketball servitude. But the economic ascent of China’s southwest has triggered tension in its northeastern stronghold.

*****

Incubating basketball: How bureaucracy keeps progress in check

All is quiet at the Liaoning Flying Leopards’ practice facility except for the murmurs between a trainer massaging a player’s ankle and the snap of Zhao Jiwei’s flip flops breaking the silence as he walks along the sidelines.

Zhao Jiwei’s the starting point guard for China’s national team and one of four players from the Flying Leopards consistently chosen to represent China on the international stage. He exudes a natural confidence. Although just 6-foot-1, Zhao Jiwei’s tightly built. His veins run noticeably down his arms, while his calves look swollen above the neck of his ankles. He wears all black, including a t-shirt that reads “Bad Five Fight For Hoop.”

The workload endured by Chinese players is heavy. In addition to year-round overtraining—with the exception of Chinese New Year—players are expected to be available for national team commitments. Between various FIBA tournaments, Asian Championships, exhibitions and other provincial and national level competitions, the wear incurred by Chinese basketball players is visible.

“I’m always switching between the club and the national team. This is not a good system for me. I’m always changing roles and there’s constant demands. I feel this is bad for my own progress,” said Zhao Jiwei, who will travel to Tianjin for the 13th National Games in two weeks time – one of many commitments Chinese basketball players are often required to participate in.

Until recently, players weren’t asked to participate. They were obligated.

“In the past, the letter with a CBA letterhead say, ‘You must play for us, you should feel honoured.’ But Yao Ming has said, ‘No, don’t do that.’ Instead, ‘Hopefully you can join this journey with us. Looking forward to hearing from you soon.’ This is the new trend – you need to respect the kid,” Xiang Cheng said.

Zhao Jiwei is a frequent member of China’s national men’s basketball team. He competed on behalf of Liaoning province at the 13th National Games in Tianjin. Photo by: Andrew Savory.

The National Games hold special significance for Chinese bureaucrats. They are the ultimate chance for sports bureaus to prove that their province is elite in comparison to others. It’s also a crucial time for bureaucrats to improve their chances of keeping their job. Sudden firings and lay-offs are known to follow an embarrassing result.

Yao Ming’s arrival as the first non-government president of the CBA has brought hope for change. However, the topic of consolidating the power of China’s sports bureaus and bringing reform to the sports school system has been raised before, only to be snubbed in advance of Beijing’s recent Olympic bids.

“For the government to send kids there, the schools must promise results, so they won’t change the ways they train,” Zhang Aihong says. “To guarantee that China is competitive at the Olympic Games, the system must promise victory. If it changes, who will guarantee the result?”

The National Games have a big impact, especially for a team like Liaoning, which is 20 per cent owned by the state and 80 per cent privately. When the government has a hand in the team’s affairs, the expectations and demands of the province supersede players’ individual freedoms.

“If you’re a pro club that is also a government owned club, your pro team system is based on the sports bureau’s system, which makes the National Games so important for a team like Liaoning,” Xiang Cheng says. “It’s the key event for sports bureau officials to get promoted, to guarantee a salary raise, or just to keep their jobs.”

But the government’s influence on the lives of Liaoning’s basketball players runs deeper than national and provincial duties. When youth in Liaoning are herded into the junior system, they sign a contract that binds them both to the CBA professional club and the provincial government. If they want to leave, they require two stamps of approval. One from the team, and one from the sports bureau.

Yang Ming is the Flying Leopards’ captain. The aging veteran saw his minutes dip in favour of upstart guards like Zhao Jiwei and Guo Ailun, the latter labelled by many as the “best guard in Asia” and a potential export to the NBA.

Yang Ming had been fielding offers from other teams for as many as five years. He was inching towards his early 30s and wanted to end his career off on his own terms, not the government’s.

“The situation for him is very special and typical. As a club, we don’t own the player. We pay the player. Sports bureau own the player because they pay for everything since they’re maybe eight or nine years old,” Xiang Cheng says.

“So, if you want to go, I won’t let you go for free. There’s no way. With Yang Ming, I won’t say he gave up, but he doesn’t have the dream to go to another team anymore.”

Yang Ming’s case is one of the main reasons why prospective Chinese NBA prospects have difficulty attracting sustained interest from NBA franchises, let alone outside their own province of Liaoning.

A row of cubbies where players’ shoes were kept inside the practice facility owned by the Liaoning sports bureau. Photo by: Andrew Savory.

Xiang Cheng served as a translator for one of Liaoning’s other players, He Tianju, when the NBA’s New Orleans Pelicans came calling in 2015. New Orleans needed three-point shooting and wanted the Chinese sharpshooter. The Pelicans offered to bring He Tianju to the NBA’s Summer League showcase in Las Vegas.

He Tianju was injured at the time and Liaoning’s management was skeptical of the Pelicans’ offer. Xiang offered to write a formal letter on behalf of New Orleans. A letter of clearance was issued under one condition. He Tianju must return to Liaoning afterwards.

“Because of Wang Zhizhi’s experience. Teams are always asking, ‘Who does it mean? Who are you?’ They worry about tampering from other teams,” says Xiang Cheng, who has translated for a number of NBA and CBA stars.

The red tape of NBA-CBA contractual negotiations is often enough to dissuade players from committing to the pursuit of an international opportunity. He Tianju is just one of the latest Chinese players that have made an appearance in the NBA since Yao Ming’s retirement, but have failed to stay.

A sense of ownership over players permeates through Chinese basketball. During the season, the Flying Leopards live together in Benxi, a short hour’s drive from the capital of Shenyang. The city was built on the backs of coal miners and steel production. Import players like Lester Hudson often travel to Shenyang for leisure, but domestic players without Guo Ailun’s status are governed by a different set of rules.

Players aren’t allowed to leave the dormitory once the front gate of the team’s residence is closed at 10:30 p.m. Cell phones are taken away and the Wi-Fi is turned off. Monitors are observed between 1 a.m. and 3 a.m. The following morning, team managers watch junior and senior team players to ensure that players eat their breakfasts.

“If you don’t eat breakfast, you’ll get fined or a penalty,” Xiang Cheng says. “If you skip, no energy, no blood sugar, more chance to get hurt – means big financial damage.”

Minor undermining of team protocol is tolerated in some cases. Team leaders like Guo Ailun are permitted to leave, but bench players like Chong Minchen have learned that such privileges don’t extend to them.

Players occupy the role of both resident and investment. To become a professional, you must succumb to a life of surveillance.

“Our development culture is different. You’re on your own as an American. Right now, in China you’re not on your own because the team pays everything for you. You’re not your own guy anymore, you need to do everything that the team wants,” Xiang Cheng says.

The practice facility in Shenyang used in preparation for the National Games is owned by Liaoning’s provincial sports bureau. Gallery photo and map by: Andrew Savory.

Liaoning is communist ideology personified. But that’s to be expected. The province neighbours North Korea and its team competes in Benxi, just a short 250-kilometre drive from the border. The Flying Leopards are merely complying with the framework for developing athletes according to the Chinese government. “The ideological and moral education work of the sports school must adhere to the guidance of Marxism-Leninism, Mao Zedong Thought, and Deng Xiaoping Theory,” reads the All-China Sports Federations’ webpage. Players must be monitored to be developed successfully for the benefit of the state.

“If I don’t trust you being professional in the offseason, if you claim you’re working with trainers, who knows if you’re just hanging out for three months?” Xiang Cheng says. “I don’t want to make any damages – I don’t trust you not to. I want you to practice in front of me.”

Despite years of success, some predict that Liaoning’s dominance may soon come to an end. Private clubs with corporate backing from Guangdong and across China have begun harvesting Liaoning’s sports schools in cities like Anshan, Dandong, Liaoyang and Fuxin.

Zhang Xuefeng fears that the provinces’ economic decline and the team’s ties to the government are part of the reason why the Flying Leopards have a depleted junior team program. Photo by: Andrew Savory.

Zhang Xuefeng has watched the team’s stockpile of talent diminish since becoming manager of Liaoning’s junior program. Schools like the Fuxin Basketball School used to supply players to the team, but the price has gone up in recent years, leaving wealthier clubs from southern China to compete among themselves for the nation’s top talent, Zhang Xuefeng said. He fears that Liaoning’s success will dwindle without the finances to compete in the auctions for youth players.

“We have gone to Fuxin to talk about players and they’ve told us that they won’t give us players unless we pay. No money, no players. We offer less,” Zhang Xuefeng says. “It’s hard for me. Me and the Fuxin Basketball School, we have no communication. We are not welcome sometimes.”

*****

Breeding commodities from policy

The entrance to the Fuxin Basketball School in Fuxin, Liaoning, China. Photo by: Andrew Savory.

A cloak of rain falls over a sinking city.

Sulphur chokes the air and paints the skyline with a bleak demeanour. Many of Fuxin’s buildings are a uniform grey. The city’s just shy of two million residents and grew alongside the largest open-cast coal mine in Asia. That all changed in 2005 when an explosion at the plant took the lives of more than 200 workers and signalled its closure. Fuxin’s been working to respond to decades of over excavation that have weakened the city’s foundation.

Basketball has taken the throne in the city where coal was king. If Liaoning is the bedrock of Chinese basketball, then Fuxin is its current epicentre. The sport’s prominence is by design. The State General Administration of Sport declared Fuxin as one of 15 special “Basketball Cities” in 1999. The label brought policies tailored towards promoting the sport in the city by building courts and distributing basketballs, while also ushering the opening of the Fuxin Basketball School on September 24, 2003.

The school has produced players for China’s national, professional and university level teams, but entered a new category of prestige in 2016 when Zhou Qi was drafted by the Houston Rockets. Zhou Qi became the first Chinese player to step onto a regular season NBA court since Yi Jianlian in 2012.

The relationship between the Flying Leopards and the school has broken down. Liaoning normally paid in the vicinity of 20,000 yuan ($3,176 USD) to acquire a player from the school, Zhang Xuefeng said, but Fuxin has begun refusing what it deems to be low-ball offers.

Zhou Qi himself is originally from Hunan province, but attended the school in Fuxin, before later playing for the Xinjiang Tigers. Given Liaoning’s firm hold on player mobility, it’s hard to believe Zhou Qi would’ve been allowed to sign with a rival club like Xinjiang, a title threat to Liaoning.

“I think the school profited off selling him to Xinjiang, some ridiculous number, like multimillion yuan,” Lukas Peng said.

The school’s president, Li Ming, is the deputy director of the Fuxin Sports Bureau. He was said to have been away in preparation for the National Games in Tianjin, but Zou Yan Xia, the school’s principal, was there.

Chairman Mao overlooked the city just 10 minutes away from the school, dressed in his trademark suit jacket with his right-hand held high, his left at his side. A labourer’s appeal to the people, made timeless by stone.

A thin canopy of trees stretched over Yuhong Road, casting a punctured shadow. The embankment of trees stopped and the sprawling courtyard of a 30,000 square foot complex appeared.

The front entrance of the Fuxin Basketball School consists of a retractable steel gate, a police station and promotions of past athletes. Photos by: Andrew Savory.

Zou Yan Xia sat inside the principal’s office. The white walls of her office were mostly bare. Potted plants sat in front of the windowsill next to picture frames of past tournaments. She insisted on showing the school’s trophy room on the sixth floor. Zhou Qi wasn’t just the school’s must prominent export, he was their premier marketing tool.

A poster of Zhou Qi alongside fellow national team member Yi Jianlian took up nearly an entire wall in the staircase. Zhou Qi’s presence filtered into the trophy room. Above the doorway sat a rectangular picture frame, encased was a signed letter of thanks from Zhou Qi. Two marble pillars rest atop a red-carpeted platform at the front of the room, each with its own stone sculpted basketball. Behind the pillars is the red and yellow CBA crest. The two pillars are dated 1999 and 2003, a nod to the government’s declaration of Fuxin as one of China’s chosen basketball cities.

“Mr. Li Ming, our headmaster, found him, and take him to our school. He came here at 9 years old. Very, very young,” says Xu Xiao Fang, an assistant at the school and Zou Yan Xia’s translator. “He looks for players who are confident and flexible.”

The description fit Zhou Qi perfectly. Standing 7-foot-2 with a wingspan stretching more than seven and a half feet, Zhou Qi is the physical specimen Chinese basketball desires.

The conversation grew colder on the topic of the school’s relationship with CBA teams. Xu Xiao Fang began to answer questions on behalf of Zou Yan Xia, before finally referring to Zou Yan Xia when asked about how Zhou Qi had come to sign a contract with Xinjiang and whether he had registered with the Liaoning sports bureau. The school exists under the banner of the CBA and has provided 70 to 80 combined players to the CBA and the Women’s Chinese Basketball Association (WCBA), Xu Xiao Fang said, motioning to the doorway.

Zou Yan Xia, seen in the left photograph, offered a tour of the Fuxin Basketball School’s trophy room and showcased both the school’s, and Zhou Qi’s (seen shooting a basketball) achievements. Photos by: Andrew Savory.

Institutional sports schools have fallen out of favour with many Chinese families, but the traditional approach to training born within them has carried forward into private academies like the Fuxin Basketball School, where players reside on-site throughout most of the year.

“The number of sports schools may be going down, but new schools that specialize in basketball train the same way. The players who didn’t make it from the sports school system just become coaches and teach what they learned to younger players,” Lukas Peng said.

The school’s website said that admission was based upon specific height requirements. Males are listed as having to be at least 175 centimeters while females must exceed 165 centimeters, according to the school’s admissions page.

Zou Yan Xia denied the height requirement for admission when asked. Xu Xiao Fang answered on her behalf, “When they have personal abilities, we’ll take them to our school.”

Players deemed capable of becoming professionals stay at the school between the ages of 9 and 15. Zou Yan Xia described the span as a two-way relationship where the “CBA can come here to search for players, and our school can send our players to the CBA.”

She became distant when asked about the recruitment process that sees the school supply players to various professional clubs. Her tone hollowed and Xu Xiao Fang’s translation grew quiet.

“Not the Liaoning professional team,” Zou Yan Xia said. “They don’t come here often.”

She wouldn’t elaborate on why the relationship with Liaoning had deteriorated or the contractual clause that requires the Fuxin Basketball School’s students to return from the professional team when required.

“If we need them, they will come back,” Zou Yan Xia said. “That is a rule.”

“Do teams pay for players?”

“Yes,” Xu Xiao Fang whispered before circling back to Zou Yan Xia. Lunch was over.

She offered to answer more questions by email, but ultimately did not. Three days later an email arrived with both a Mandarin and English translation of what was the equivalent of a news release. No questions were answered.

The Fuxin Basketball School is sold as a new type of institution, but when the curtain’s pulled back, it’s still a government school that has the same issues born from abiding by the rules of a communist dictated league. The province’s struggling economy has paved the way for affluent private-owned clubs that are willing to pay the fees necessary to entice the school to part with its players. A student body from 23 provinces fills its corridors with children of varying lengths and sizes – the best bound to be sold to teams that can afford them.

*****

Balancing cultures: Spurring change inside an East meets West enterprise

It’s day one at player development coach Ganon Baker’s summer camp at the CBA Dongguan Basketball School (DBS). More than one hundred students clad in white school t-shirts sit cross-lagged, awaiting Liu Mutian’s next translation.

Baker is crouched at front of the room, pounding a basketball against the floor with one hand while tossing and catching a tennis ball with the other, all while telling a story about his time training with Kobe Bryant. Baker’s here to preach his brand and the NBA’s gospel.

He divides the group and instructs the players to perform a crossover underneath a bouncing tennis ball. Few manage the task. Balls begin to collide and scatter across the room. Other children start shooting on available hoops until a nearby coach guides them back to the group. One parent retrieves his son’s tennis ball and attempts the feat himself.

“Number one, you can’t be soft. If I say go hard, be quick,” Baker says. The group is divided up into sub-sections, but not before Baker reminds parents to consider a purchase of his training video before leaving.

For 8,000 yuan ($1,265 USD), kids at the camp receive nearly two weeks of summer training from Baker and accommodation at the complex. The camp is just one small facet of the school, which was established as a cooperative full-time middle and high school run by the CBA and the NBA in 2011. Its mandate is to train players and coaches in hopes of creating what former technical director of the school Bruce Palmer called “pathways inside and outside of China.” Students that can afford the school are exposed to a decorative environment that surrounds youth with NBA iconography. Even the elevators are coloured to match the NBA’s two conferences.

DBS greets students and visitors with NBA iconography and memoribilia at every turn, whether it be posters, trophies, or the jerseys worn by many of the school’s students. Photo by: Andrew Savory.

The school stands as the embodiment of a several thousand square foot promotional campaign. It’s also a manifestation of one of the most unique partnerships in East meets West business. The NBA announced in 2014 that it was partnering with China’s Ministry of Education to develop a “joint fitness and basketball development curriculum,” NBA Commissioner Adam Silver said in a news release.

In widening its arms to western business, China has offered American mega-corporations the chance to monetize the lack of organized competitive sports in its school system. Three more NBA training academies have arrived in tow. But as Palmer learned, fulfilling a mandate drawn up thousands of miles away at headquarters in New York City requires constant readjustment to satisfy the demands of the world’s hungriest basketball market.

“It was a cowboy thing my first year. At the end of the school year the principal came in and told me that I had to fire two coaches just to make a statement,” says Palmer, who left the school in April 2017 after serving as its second technical director for five years.

“The technical detail of what’s being taught is lacking and there’s no pathways for coaches either. If you hadn’t played in the CBA or prior to that played for China on their national team, you could never be a CBA coach.”

Many of China’s sports bureaus and professional basketball ranks are filled by friends, family and close ties. Pre-existing relationships often influence who occupies positions of power in many institutions. This school is no different.

The school’s headmaster, Li Qun, is a former CBA player and coach for the men’s national team. His older brother, Li Lun, is the school’s administrative director. The oldest of the brothers, Li Ning, is the head coach of the amateur training program. Chu Hui, the school’s vice technical director, is also Li Qun’s sister-in-law. The school’s owner, Yu Shuyong, owns the CBA team that Li Qun used to coach, the Dongguan Leopards (now in Shenzhen).

Palmer arrived in Dongguan having coached in Japan and Australia. He’d been warned in advance that the school wasn’t elite, but wanted to be, by Greg Stolt, vice president of basketball operations for NBA China.

The school neighbours the Dongguan Sports School. Together, they sit wedged between a series of surrounding factories. It doesn’t take long to get a sense of how pervasive basketball is in Dongguan. Rims with stained mesh hang off building sides of nearby factories. Courts are everywhere.

From hazy skies to courts wedged between shopping complexes and factories near DBS, basketball ripples through everyday life in Dongguan, Guangdong, China. Gallery photos by: Andrew Savory.

Like much of Guangdong province, Dongguan is a manufacturing hub. The city’s known for its cheap production of garments and electronics, particularly for companies like Samsung, Toshiba and Apple. Dongguan has risen to be one of the export leaders of China and was responsible for 16.6 per cent of Guangdong’s total exports in 2016, trailing only Shenzhen, according to Hong Kong Trade Development Council data.

Palmer arrived at DBS’ brick entrance in 2012 with a different task than the nearby factories – to not only work towards sending players outside of China, but prepare them for life after basketball in China.

“There were no academics the first year. The headmaster said this is a basketball school, we don’t care about academics. Well, you can’t have one without the other,” Palmer said.

The school’s been an experiment for how malleable Chinese basketball can be. Little progress was made by Palmer’s predecessor, Ron Ekker, who left DBS after a year in 2012. Students were required to pass a series of strength and athletic tests to earn admission, but Palmer said that “if you had money, they would take you because they’re trying to get a return on an investment.”

“The guy that I succeeded, he didn’t do anything that the job asked for. You were meant to set up a coach’s education training program. I didn’t see it, he didn’t leave anything there,” Palmer says.

Attending DBS doesn’t come cheap. Nor is the student body comprised of your average middle-class child. Some scholarships are offered based upon athletic talent, but tuition for the majority of students is 38,000 yuan ($6,021 USD) a year, well above the per capita disposable income of an urban household that was measured at 31,194.8 yuan ($4,971.36 USD) by the National Bureau of Statistics of China in 2015.

At first glance the school was what Palmer called “window washing.” Players were being admitted, money was being made and coaches had jobs, but no progress was being made to offer coaching superior to that which players would receive from a PE teacher.

That’s one of the reasons Chinese coaching has yet to take a step forward. There are no incentives for career development. The paradigm of CBA coaches exists largely as an old boys’ club that sees a circle of former players return to coaching once they’ve retired. Rarely are outsiders let in.

There is no upward trajectory for Chinese coaches in the school system. Coaches are often inserted into a position they’re underqualified for. Palmer wanted the school to be just as much about improving career flexibility for the teenagers that filled its dorms as it was for the coaches handling the drills.

“The level of coaching compared to the West – it’s shocking. Even in Japan, much better coaches. Korea and Taiwan, much better coaches. It’s limited pathways and limited coaches education,” Palmer says. “Why bother? You got a job for the rest of your life, so does it matter if you become a student of the game? It’s a real missed opportunity.”

Junzu Qi had said the same thing of his initial time as a coach at Five-Star. Although he’d grown up in China’s most powerful basketball province, he had never seen a coach run a practice with a lesson plan until he arrived in Shenzhen. He began staying behind after Pierce, who is also Five-Star’s director of coaching, to search through the garbage for the notes Pierce threw out after practice.

Palmer said that Chu Hui, who coaches the school’s varsity teams, was one of the hardest to convince. A lanky 6-foot-2, she’d been a member of China’s women’s national team at the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta.

Chu Hui was born into a generation that was taught that duration of training translated to results. She grew up in Dalian in Liaoning and was the tallest of four sisters. When she was 12 she was recruited to play for an army affiliated team in Guangdong. Today, she’s one of Palmer’s biggest converts.

“Once the philosophy changes, Chinese basketball can improve,” she says. “Bruce brought a kind of thinking that was different than other systems in China. Players don’t work as hard as we used to, but players’ technical skills and understanding about basketball is higher than it was.”

Chu Hui has been working to adapt the regimented style of coaching that she learned as a player into a more detail-oriented and technique-based approach to basketball. Photos by: Andrew Savory.

International strength and conditioning coaches working in China have raised concerns regarding the amount of stress put on young children. Chu Hui and other coaches at the school were used to training players for four hours at a time, twice a day, until training hours were broken up.

“Even 14 is quite early to get them in these specialized programs. They become basketball robots – not enjoying the game for what it is. The element of play gets taken out of it,” Parsons says. “Generally, the strength training for young kids is horrible. They do adult programs when they need to be doing structural programs for their future development.”

Instead, Chinese coaches want tangible and quantitative results. To enforce results, coaches often resort to forms of physical or verbal punishment to assert the hierarchical relationship between coach and player.

Cai Zepeng was 15 when he joined DBS. He had never played basketball before, but coaches and friends had noted his height and recommended he pursue the sport. Cai Zepeng soon realized that just practicing wasn’t going to be enough.