Destination: Wildfire

Flames, floods, and the fight to adapt British Columbia's tourism industryBy Adam van der Zwan

Chapter 1

The Four Horsemen

On a mid-August afternoon in 2018, a street full of tourists in an isolated gold rush town in eastern British Columbia watched in awe as a hellish shade of deep orange enveloped the sky and swallowed them in darkness.

The onslaught began at 2:30 pm. Fingers of thick smoke from a group of vicious wildfires northwest curled menacingly over the edge of Barkerville – an entire village preserved in the mid-19th century gold-rush era. After twenty minutes, details in the heritage streetscape were lost to shadows. The cluttered lineup of over 100 age-old wooden buildings, including the Wake Up Jake Saloon, the Goldfield Bakery, and McPherson’s Watchmaker’s Shop, had all become a collection of indistinguishable A-frame rooftops.

When the streetlights switched on, the horse-drawn carriages were no longer rattling through the dirt. A hastily scribbled cancellation notice was tacked to the box office window at the Theatre Royal. The usual afternoon chatter from a town-full of time travelers had fallen to a low murmur.

The air had become cold, and the streets were nearly deserted.

Over the course of an hour, Barkerville darkened in the smoke. (Adam van der Zwan, 2018)

At that time, Julia Wheatley leaned on the doorframe of her ‘office,’ a creaky, green and white character home once occupied by a miner and his wife in 1904. “I’m waiting for the four horsemen of the apocalypse to ride in” she said through a soft but worried voice. She observed the eerie sky. “The birds have all gone. None of the leaves on the trees are moving.”

Wheatley plays the role of “Julia Wendle,” welcoming visitors into the house, teaching them its history, and immersing them in the domestic life of a gold-miner’s wife. She wore a dress of plain burgundy fashionable at the turn of the 20th century, and her greying hair was tied up in a modest bun. Through round spectacles, she peered at one of her colleagues down the road, a man in an old-fashioned vest, who appeared shell-shocked as he sauntered the empty street. They made bewildered eye contact and each shrugged their shoulders.

In her 15 years working at Barkerville, never had Wheatley witnessed the weather change so dramatically, much less so many visitors on a peak-season afternoon turn and exit the town of their own accord. “Barkerville is a destination site, so everyone is from somewhere else,” she explained. “When the world looks like this, we want to be closer to home.”

T he sudden emptying of Barkerville resembles a frightening transformation B.C.’s tourism industry, one of the province’s top economic drivers, has experienced in the last couple years. The continued threat of seasonal extreme weather events in the province’s interior – floods, wildfires and lingering smoke – now have tourism operators across the province not only concerned for the health and safety of their customers, but for the future of their businesses in a beautiful, pristine province traditionally marketed as “the Canada you imagined.”

Wildfire has always been a natural and integral aspect to sweltering peak-seasons in the heavy forests, though the weather during the summers in 2017 and 2018 was what some would describe as nothing less than evil.

Because of the province’s complex geography of jagged mountains, rolling forests and coastal lands, tourism in B.C. offers a diverse range of experiences, from remote mountainous hikes to whale-watching along the Pacific shores. The past two summers have created an imbalance in tourism, however, as many tourists have fled the dry, smoky interior for the relatively haze-free coast or Alberta.

In 2017, while the industry contributed $9 billion in GDP to the province’s economy – six per cent more than the previous year – many tourism operators in central B.C. saw their visitors and revenue numbers drop dramatically due to evacuations, road closures, and the lingering uncertainly afterward. Some had lost almost 100 per cent of their expected income, and many struggled again in 2018 when the smoke returned in greater concentrations.

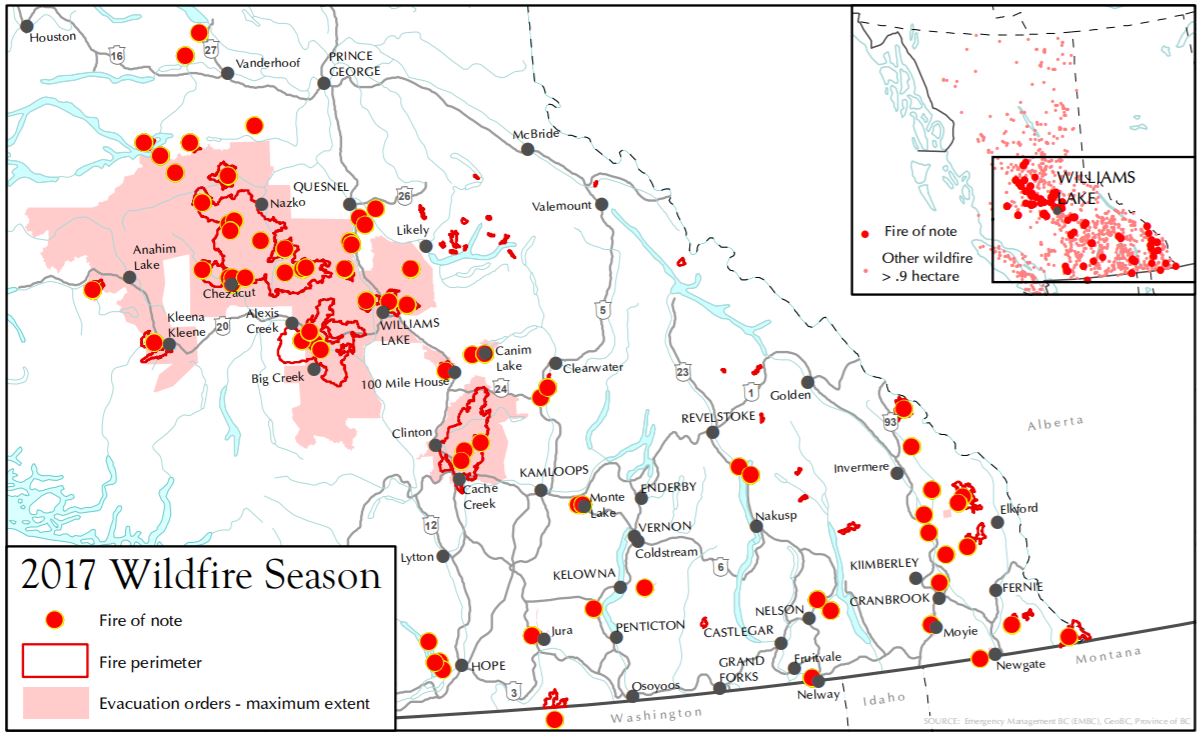

The morning that hell descended on Barkerville, a collection of massive wildfires that had burned for over two weeks were swelling into the Nechako Plateau in central B.C. A number of small communities along highway 16 west of Prince George were evacuated, and most residents couldn’t return home for more than a month. Meanwhile a slew of wildfires had peppered the rural farmlands south in the Cariboo region, west of Quesnel, and were rapidly intruding on a multitude of ranching getaways.

In Prince George that morning, the smoke had accumulated so much that residents there were stunned when they pulled back their curtains at 9 AM to face complete darkness. Thick, floating ash had brought health outdoors to a “very high-risk level,” indicated by Canada’s Air Quality Index. The angry, black smog then unfurled its way east, straight over Barkerville, over the province of Alberta, reaching more than 2,200 kilometers to Winnipeg, Manitoba.

The Edelmans, a family of four who’d arrived from the Netherlands for a three-week trip through B.C., were anxious when they saw the deep orange sky in Prince George that same afternoon.

“It was a bit scary,” said Margaret Edelman, standing with her family outside Prince George Information Centre the next day. Having booked their holiday in February, she said her family hadn’t learned of the possibility that wildfire could interrupt their trip. Even as they now traversed one hazy town to the next, the visitor centre workers they spoke with made no mention of staying safe or prepared in the smoke-ridden areas. Instead, it seemed to her they’d avoided the topic.

“We planned to go (south) to the Okanagan Valley, but there’s smoke there too,” Edelman added. Their situation mirrors those of many other foreigners who’ve visited the province the past couple summers – disappointed with a lack of guidance on the potential hazards, unaware of where to find the proper information, and having to change their travel plans at last minute to avoid the smokey areas.

By mid-August 2018, the near entirety of the most ecologically diverse province in Canada, with more than 60 million hectares of temperate, boreal and dry pine forests, was blanketed in a tumbling, ominous layer of smoke that could be seen from outer space. At the end of the summer, the 1.35 million hectares burned had officially shattered 2017’s record of being the worst wildfire season in B.C.’s history. The thankful difference between this season and the last was that the 2018 fires hadn’t reached as many communities.

Ms. Florence Wilson, played by Danette Boucher (Adam van der Zwan, 2018)

Standing in the middle of Barkerville’s main street with a parasol under her harm, Danette Boucher – or the 19th century’s Ms. Florence Wilson – gazed in shock at the darkening sky. For 20 summers, the town has been home to her acting career.

“Barkerville, by this time in my life is like an old friend, and suddenly I felt like bursting into tears when the sky turned orange because it was nothing I’ve ever seen here,” she said in a false but impeccable British accent. The confident English saloon keeper she portrayed spoke stoically, almost indignantly, with dramatic flair.

An hour after the darkness fell, the smoky air had lightened, and a few of the tourists had trickled back in. Boucher, wearing a small straw hat and a dress with a bell-shaped turquoise bottom, recounted the previous summer when a tourism season poised to be the town’s most successful abruptly “stopped dead.” By September 2017, an unprecedented 1.2 million hectares of land had burned through large swaths of south-central B.C., displacing more than 65,000 people.

Earlier, in July, the highway through the southern Cariboo region was closed entirely as thousands from the towns of Williams Lake and 100 Mile House were evacuated, many of them driving up to Quesnel, along the northern Cariboo stretch. The turn-off east to Barkerville lies on this section of the highway. It’s an isolated, dead-end road.

Barkerville sits at the tip of a dead-end road, in the eastern Cariboo region of B.C. (Photo courtesy of Google Maps)

“Highway 97 (south) closing was one of the worst things that could have happened to us,” said Boucher. “Normally I give [tourists] the morning town tour at 10 o’clock, the first show of the day, and there are forty or fifty people waiting for me. When the highway closed there would be three people waiting, or even no one.”

A University of Victoria museum theatre graduate, Boucher had spent most of her career portraying gold rush-era women in the town. The last few summers had been dedicated to historical tours and street theatre, she said, and multiple times a day she acted in comedic, impromptu skits that stop visitors in their tracks on Barkerville’s main street. In 2017, when visitor numbers tumbled, Boucher’s work took an emotional turn when she realized many of the visitors who did arrive were grief-stricken evacuees.

“Talking about the wildfires became different,” she explained, adding that before briefing her tour-guests on wildfire updates, she would warn them. “We had to cut performing a fire brigade song at the Theatre Royal […] We had to be really sensitive.”

Boucher began approaching her street skits with a moral sense of duty. “Even if it was one person from the public, even if the people from the photo studio next door had seen the play a million times, it was important that we just kept going,” she said.

O ld Mr. Grimsby, a kooky, saloon-loving gold-miner played by Dave Brown, lives on the edge of town in a little hut next to a giant wooden water wheel. Here, visitors gathered twice a day to learn how to “mine in the Cariboo.”

To play the part, he wears earthly colours – a light vest over a brown buttoned shirt, and a floppy leather gold miner’s hat above his bushy, unkempt beard. Now 63 years old, Brown has played Mr. Grimsby since 1984, and is the oldest member of the interpretive staff.

He can confirm that no smoke event as frightening as the one he’d witnessed an hour prior had ever occurred over Barkerville the last 34 years.

Mr. Grimsby, played by Dave Brown. (Adam van der Zwan, 2018)

As the day turned to night, his pulse raced and he immediately thought of his home in Quesnel. “I should cancel my show,” he recounted. “I should go home. I should make sure my house is okay. I should make sure my wife is okay. Should she come up here? Should I go down there? Where are the conditions worse?”

He was reminded of grief embedded on the faces of those who’d taken refuge at Barkerville’s campsite the summer before. Some people had lost their homes and were sleeping in their cars. “They just felt that Barkerville was a safe, familiar place to come to,” he said. Brown and his staff spent a lot of their time “counselling” the evacuees, some of them entire families, who were victims of wildfire. During the day, they’d share stories with each other, and the actors would talk out of character “as compassionate people,” he said.

“The restaurants would give them a free meal,” he added, “even when the business owners here (in Barkerville) – the merchants, the stores, the restaurants, the people who actually depend on visitors for their livelihoods – weren’t making any money.”

By the end of the 2017 season, Barkerville had lost a steep $1 million, not including the revenues lost by the business-owners who occupied the shops in the town, according to the town’s CEO Ed Coleman. A typical season would yield about $500,000 in gate-fee revenues, though after the deadly August, the town had managed just over half that amount. In 2018, the town had quickened its pace, though it wasn’t seeing as many tourists as it usually did.

Brown floated the phrase “the new normal” into the ether. He’d noticed the seasons change over the years, the July and August weather had become hotter and dryer than what it was, not just in B.C., but all over the world. Massive wildfires were destroying much of California. Devastating flames had also taken hold of Greece in southern Europe, the United Kingdom, Siberia, and were raging in Sweden as far north as the Arctic Circle. In Canada, emotions were still fresh from the 2016 wildfire that forced 88,000 residents out of their homes in Fort McMurray, Alberta.

“If we see more of it, we’ll just have to adapt to it,” suggested Brown.

Back at the Wendle house, Julia Wheatley adjusted her glasses. “Anyone who says the climate is not changing has not looked outside,” she said quietly. “Yes, the climate is changing.”

(Adam van der Zwan, 2018)

Chapter 2

The Gustafsen Summer

T he Gustafsen fire began with a series of ruthless dry lightning bolts over the conifers in south-central British Columbia. The unusual scorch of early July 2017 stoked flames among the Douglas firs and lodgepole pines along a narrow forest service road, just seven kilometres west of 100 Mile House. The fire leapt northward towards the homes in 105 Mile House, leaving behind a graveyard of charcoaled branches.

As the wildfires merged, Emmy-Lou Stoeter watched a mass of ugly black plumes billow over the tree line south of her horse sanctuary and trail riding company. The horses at the 108 Mile Stables snorted and whinnied in the open field, unaware of the inferno that, by the sweltering Thursday afternoon, had visibly made its way closer to their rustic vermillion barn. The customers aligned at the gate had a different perspective.

“You could tell people were panicking,” Stoeter said, recalling the line-up at the gas station nearby. “I thought, if this gets any closer, we’ve got to get out of here and we want to be prepared.”

Stoeter and her horse guides immediately called off their afternoon riding trips and sent away the tourists, then stood for a moment at a loss, watching the horses flick their tails. Without enough trailers, how would they haul 38 horses, two llamas, and a donkey away as quickly as possible? Stoeter had no choice. She ran into the barn’s office and picked up the phone.

After a significant spring flood season, B.C.’s provincial wildfire crews noted a mild summer in many parts of the province, though in June the fire risks began to rise steadily with the intensified heat. The thunderstorms that pelted the Cariboo region from July 6 to 8 were the catalyst for 190 new wildfires that aggressively ripped over the forests and the patchwork of lakes dotting the rugged meadow-scape of ranch lands and vistas.

Near the Cariboo highway, 120 kilometers south, fires were beginning to tear through the trees near the desert-like lands in the Kamloops region, and would expand to over 190,000 hectares of burned area through Elephant Hill Provincial Park between the highway towns of Cache Creek and Ashcroft, prompting tens of thousands to evacuate. Over the coming weeks it would eventually spread 100 kilometers north through the mountains until it licked at several remote lakeside resorts.

(Source: BC Flood and Wildfire Review, 2017)

The layers of B.C.’s emergency response system had activated. Local Emergency Operating Centres (EOCs) and Fire Centres were now rapidly deploying their first responders – firefighters, police officers, ambulance and social services – while Provincial Regional Emergency Operations Centres (PREOCs) had opened in the larger cities nearby, including Kamloops, to provide resources and policy directions to the local level.

Back in the Cariboo, where most of the fires had erupted, 120 firefighters from 100 Mile House and the provincial wildfire service were desperately attempting to quell flames rapidly cropping up and crippling the forests around a 105 Mile House neighbourhood.

By the afternoon, six helicopters were cutting loudly back and forth through haze, with bright-orange collapsible water buckets suspended from sling lines between their landing skids. They appeared like armoured dragonflies hovering over Watson Lake, just north of the blaze, to fill up before taking off to release targeted sheets of rain over the pressure points.

They were joined that evening by another 25-member Incident Management Team, four more helicopters and air tankers that would skim the lake’s surface. As with most fire crews, the Cariboo firefighters, who worked out of the B.C. government’s Cariboo Fire Centre, north in Williams Lake, were now facing one of the most arduous summers of their careers.

The aftermath of the Gustafsen fire. (Adam van der Zwan, 2018)

As the blaze grew to 500 hectares by the evening that same day, Stoeter suddenly found herself staring at six large horse trailers parked in her driveway at the Stables. “I literally called two friends, and they called their friends. It was amazing,” she said.

The ranchers north of 100 Mile House are a tightly-knit community, and in times of crisis, they share resources – farming tools, vehicles, and animal feed – to ensure everyone is cared for. Among the group was Stoeter’s sister-in-law who’d driven over an hour from Ashcroft with a trailer they were able to cram nine horses into.

Stoeter had enough room for all the remaining animals except two. One of the horses she’d acquired recently was still “semi-wild,” and refused to move into the crowded trailer. “I couldn’t keep him with the others, but I couldn’t leave him there alone,” she said. Heart-wrenched, she left the two horses standing in the barn with her contact information attached to halters around their faces. She then left the wooden gate open should the oncoming flames force them to flee.

The trailers rolled out as the foul smoke rolled in. They drove the animals up the highway to Stoeter’s home ranch, a quaint, secluded acreage about 20 minutes north near the community of Lac La Hache. It was a relative safe haven that would remain on evacuation “alert,” rather than “order.” There she wedged them into her own barn for the night, before settling in nervously with her husband and year-and-a-half-old son.

The choppers and tankers continued in vain to try to control the fires through the night. The dark hillsides were emblazoned with orange and yellow flecks in what resembled a molten nighttime cityscape. Come the morning, the Gustafsen fire had expanded from a few hundred hectares to 1,200. The Cariboo Regional District would order 3,600 residents of 105 and 108 Mile Houses to evacuate and report to their nearby emergency centres. A provincial state of emergency would be called, and would last 70 days, the longest in B.C.’s history.

Stoeter lay awake that first night in shock and regret at the reality of the day. This fire is enormous and it’s growing, she thought. She pictured the stable, her livelihood, up in flames. She pictured the horses engulfed in fire as they fled the barn, and her heart hammered into the morning.

2 017 was incredibly costly. During the two-week evacuation period in July, Stoeter and her family rooted themselves in their Lac La Hache home with an air purifier as the smoke filled the crevices around the house. Without enough pasture to feed more than 30 horses, Stoeter quickly burned through a month’s supply of her winter hay reserve and was forced to drive the dusty back roads to other secluded ranches to purchase expensive bales.

Meanwhile, the animals had become lethargic and irritable in the smoke, and many of them had developed coughs. Without exercise, they squabbled amongst each other, and Stoeter soon discovered fresh, bloody wounds on a few of their shins. One horse was even found with a broken splint bone.

When the evacuation order finally lifted two weeks later, Stoeter’s veterinary bills covered pricey treatments, including for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease that left one horse wheezing whenever her heart rate increased. Stoeter and her guides returned to the stable to find the two horses they’d abandoned, who’d been monitored by a local police officer, alive and safe.

After her stable re-opened, the month of August was the worst for business she’d ever encountered.

“We basically sat here twiddling our thumbs all month,” she explained. Negative media coverage on the wildfires, and the relentless smoke had frightened away many of the tourists, despite the highway re-opening. “We were down to maybe one ride every four days,” she recalled. “I easily lost three quarters of what I usually make, not to mention all the extra expenses.”

Like Stoeter, most of the tourism-related business in the Cariboo region suffered horrendous financial losses that summer. A wildfire economic impact report, released by the Cariboo Chilcotin Coast Tourism Association (CCCTA), found the average financial loss at around $73,000. A third of the tourism operators, in a region marketed as a rustic ‘cowboy’ experience, complete with rodeos, golfing, fishing and historic railways, suffered losses between 61 and 100 per cent of their annual revenues.

Stoeter, along with nearly 70 per cent of tourism businesses, hadn’t purchased any business interruption insurance. “It takes quite a chunk out of my finances,” she explained. The report reveals that tourism operators were concerned when the insurance wouldn’t cover many of the losses suffered due to smoke, tourists’ hesitancy, evacuation alerts or highway closures, and would only cover structural damage and the revenues lost while on evacuation order.

A conversation with Aaron Sutherland, vice president of the Insurance Bureau of Canada in Vancouver, suggested that insurance companies aren’t likely to change their policies. Sutherland sees the industry as a “canary in the coal mine.” Across B.C., it’s faced the “financial costs of the changing climate before anyone,” he said, adding that extreme weather events have cost multiple insurers over $1 billion dollars in insured losses. “Customers would do well to consider more carefully which insurance company to choose,” he noted.

Burnt forest near a residential neighbourhood in 105 Mile House. (Adam van der Zwan, 2018)

M eanwhile Destination B.C., the provincial Crown Corporation that promotes tourism internationally, had been scrambling to find where exactly cancellations were being made in areas that visitors mistook to be affected, but weren’t.

Maya Lange, the vice president of Global Marketing, maintains that the number one priority is to keep everyone safe, but said her team had “heard anecdotally” that copious cancellations were being made in areas not immediately affected. “We reached out to large global platforms like Google, Facebook, airlines, and online travel agencies like Expedia” to understand the scale of the issues, she explained.

From there, she said funding was redirected to many of the locations that were rapidly losing visitors. While 70 per cent of the corporation’s marketing funds are used domestically for its Explore BC campaign, Lange said the campaign received a boost the past couple years in part “to dispel the misinformation” and fear in those regions. Lange recounted more than 100 interviews with media outlets she took part in during 2017, in efforts to broadcast more nuanced information on what areas were open during the chaos. Sensational terms like “Smokanagan” for the Okanagan region, seemed to have completely deterred tourists from driving through.

Despite the hardships, Lange was quick to note that B.C.’s tourism industry has still grown over the previous years. “We were really nervous about how 2017 was going to shape up […] but I’m delighted to share that we’re now over an $18-billion industry,” she said.

Stoeter isn’t satisfied, however, as she sat waiting for customers to brave the hazy highway. The total losses for the Cariboo-Chilcotin region that summer were estimated at around $101 million – the hardest financial hit of any tourism region in B.C.

Emmy-Lou Stoeter (Adam van der Zwan, 2018)

A year later, Emmy-Lou Stoeter stood outside the stable barn, at the head of a brown mare named Teapot, and caressed the horse’s muzzle in her palms. A few of the trail-guides tended to their tasks nearby.

Stoeter had a calm and youthful face beneath a crop of French-braided blonde hair. A few saddled horses stood beside her with their halters tied to a log fence. Their heads were down, lips plucking at blades of grass as they waited for customers to arrive for a smoky morning ride through the trees.

The 29-year-old had spent most of her life at the stable. Raised “a minute down the road,” Stoeter fell in love with horses at the age of six and began working there as a teenager before taking ownership in 2008. Aside from her trail-riding company, she operates an equine sanctuary, adopting horses from owners who neglect or can no longer care for them, or rescuing them from slaughter houses before they’d be butchered and shipped overseas.

“Most of these horses have been with me since I took over the business,” she said, motioning to the line-up beside her. Upon acquiring the animals, she spends time understanding them. She checks for blemishes and signs of how their previous owners treated them, she ensures they have veterinary care, dentistry and foot-care, and she trains the well-behaved ones for trail-riding.

She eyed a few of the horses clopping in the hazy field. The morning was remarkably quiet and the wildfires raging west of Prince George had generously sent their smoke southward. The chilled, humid air had trapped a dense fog with a concentrated stench into the gold rush valley. “It’s disgusting. It feels like a wet campfire right in your face,” she said, crestfallen.

That morning a number of her family trips were cancelled due to air quality concerns, and the day before had been “a complete write-off,” she explained. Earlier that week a group of parents cancelled their children’s “horse-camp,” led by Stoeter. Concerned for the health of her horses, she’d also cancelled her day-long trips through the Walker Valley, where most of the smoke had collected the past couple weeks. “It’s sad because we rely pretty heavily on that kind of revenue,” she said.

Stoeter operates a “break-even business” and said she usually makes around $40,000 per year, which is then spent on veterinary bills, pay cheques, animal feed, and to the other stables’ needs. “I do this for the lifestyle,” she said bluntly. But with 2017’s disastrous fire season, and the fresh smoke of 2018, Stoeter is anxious on how her business will fare into the future – especially when the bulk of her customers arrive during July and August, the hottest months of the year.

After 2017, the costs of fireproofing her stable, along with an extensive marketing push to persuade tourists to visit, are simply too high for Stoeter. The bulk of her visitors are out-of-country tourists driving the gold rush highway in their RVs, stopping at information centres or lakeside resorts where she pays an advertising fee to display her business cards. Though the B.C. government’s $17,000 in recovery funding, given to her through the Canadian Red Cross, had been helpful, a year later she still found herself short of the remaining funds needed to pay her neighbours for animal feed.

She’s considered offering cross-country skiing lessons during the winter, and she’s now established ELS Equine Services and Rescue, an organization with fundraising opportunities. But with the prospect of a third smoke-ridden season, the financial and emotional tolls are difficult to fathom. “I can’t remember anything remotely like this, even when I was younger,” she said incredulously.

A study released in December 2018 by Environment Canada and the University of Victoria examined the 1.2 million hectares burned by the end of 2017, comparing the earth’s state of climate change with a hypothetical unaffected world. The hair-raising results found human-induced climate change to have made the extreme wildfire risks four times more likely. The potential area burned was increased by up to 11 times.

Seated on a stool in the stable’s office, which is adorned rustically with strips of tree bark and a wagon-wheel ceiling light-fixture, Stoeter reflected upon her decision to reopen her business the previous August.

“I should have said, ‘okay, let’s just call this summer a complete loss and try to start fresh after the winter.’”

The remains of a destroyed home in 105 Mile House. (Adam van der Zwan, 2018)

Chapter 3

‘Business continuity under a new label’

Joshua Chafe is pioneering work in tourism emergency preparedness. (Adam van der Zwan, 2018)

Joshua Chafe slapped a bright orange duo-tang onto the head of a boardroom table carved from finished oak. It was a mid-August morning in 2018. “The basic idea for creating this is that tourism operators should have a book they can pick up with all the information they could possibly need in the event of an emergency,” he explained.

He seated himself smartly on a plush, black desk-chair and rolled in. He thumbed through the first few pages and tapped a list of phone numbers. “Here’s all the numbers for the emergency services in the area. Out here too many people are informed by gossipy Facebook groups, when they should be asking things like, ‘who’s actually issuing the evacuation?’” He poked at a number. “There, it’s your regional government.”

Chafe spoke with vigour and clarity, as if every concept is something profoundly interesting.

“Tourists don’t read the news […] so they rely on the tourism businesses to have all the correct information, and if they don’t, things go off the rails pretty quickly,” he said.

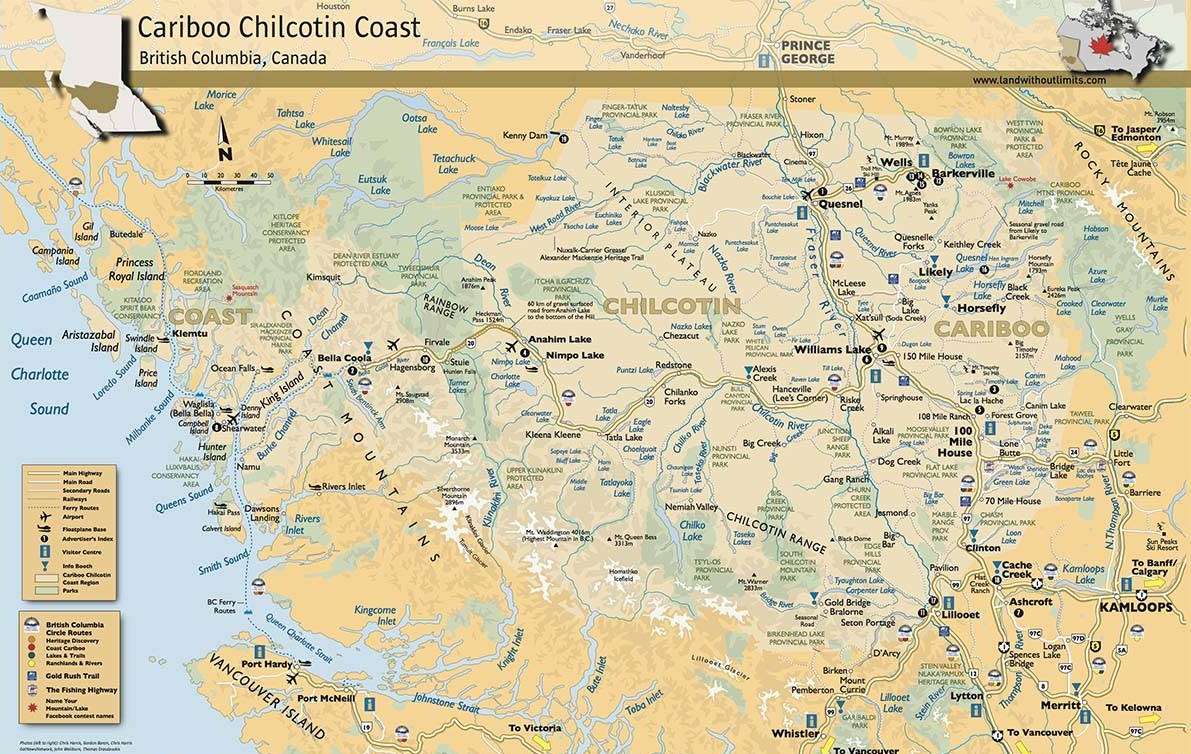

Outside the boardroom at the Cariboo-Chilcotin-Coast Tourism Association’s (CCCTA’s) office, in Williams Lake, B.C., a handful of communications professionals were clicking away at their keyboards. The association is one of six that each represent a tourism region in the province, in partnership with Destination B.C.

The office was small and comfortably scattered. Books, binders and promotional pamphlets adorned the shelves, beside plaques and romantic posters of ranch lands on the walls. Paperwork and picture frames populated the desks. Everyone had settled into a low murmur of online marketing strategies and “destination development” for the region’s tourism sector, complicated by a thick layer of smoke that had fallen over the city from the northern wildfires near Prince George.

Since June, extreme weather events had been Chafe’s top priority.

A travel enthusiast from northern Alberta, he’d hopped from one life experience to the next. After a psychology degree in Ottawa, he became a cave guider and outdoor instructor at a New Zealand Y.M.C.A., then a paramedic for an expedition company, where he voyaged to Central America and South Africa. His first venture into emergency management came when he crafted preparedness plans for a Toronto-based cycling-tour company, which prompted him to enroll at the Justice Institute of British Columbia, to become an emergency response expert.

In early 2018, then an overdose prevention worker on Vancouver Island, Chafe clicked on a job posting for an Emergency Preparedness Coordinator in the gold rush country: a novel position for the tourism industry, and the first of its kind in Canada. Chafe was hired. He boxed up his things and drove to the small, interior city of Williams Lake to pioneer himself fully in a project that would hopefully make a leap toward adapting the tourism industry to a topography ridden with wildfire.

A nthropological evidence reveals that natural disasters, from hurricanes to earthquakes, have assailed Canada over hundreds of years, though government emergency systems were only established around 70 years ago. By the late 1960s, all provinces had passed emergency management legislation, prioritizing local first responders as the land’s defenders. Since the 1980s, there’s been a growing awareness that large-scale disasters require a more concerted response from higher levels of government.

Events such as the colossal Hurricane Katrina that obliterated thousands of homes in New Orleans in 2005, helped prompt a recognized link between extreme weather events and climate change. As these events intensify across the globe, B.C.’s complex geography make it susceptible to many types of disasters that endanger communities.

In 1996, the province created Emergency Management BC under the Emergency Program Act, to provide comprehensive oversight for a local and provincial response system, which integrates emergency social services, search and rescue, and road rescue services. The BC Wildfire Service, a separate provincial entity created in 1912, provides personnel, equipment and supplies to fight wildfire on both Crown and private lands.

But with these systems in place, responders can still be caught off-guard. After a dramatic series of wildfires took hold of southern B.C. in 2003, forcing a third of the city of Kelowna to evacuate, a report by former Manitoba premier Gary Filmon, commissioned by the B.C. government and published a year later, suggested pre-wildfire mitigation efforts, such as prescribed burning, be enhanced around forested communities.

After 2017’s record-breaking fires, a new independent review entitled Addressing the New Normal suggested that since 2003 “not nearly enough has been accomplished to meet the magnitude of the threat our province faces today.” Most local governments, it said, were strapped for funds and couldn’t protect themselves.

To complicate matters, Chafe said the 2017 review barely suggests anything specific to the tourism industry in its list of 108 recommendations for managing disasters. “Considering we’re one of the largest industries in the province, we’re just not on the table,” he explained.

Statistics from Destination B.C. show the tourism industry’s growth numbers despite extreme weather events, bringing in gross revenues far ahead of the money produced from mining, the second largest industry. Since 2007, tourism has brought in over 40 per cent more than it did a decade ago, and both businesses and employment opportunities are expected to increase in the coming years.

Despite this, the industry has barely gained a foothold in disaster management procedures. During the past couple years, it has only begun to realize the need for a communications protocol to keep business owners informed, safe, and operating during difficult seasons.

B.C.’s Tourism Act mandates the Minister of Tourism to create policies that promote and develop the industry, though no polices for disaster marketing, communications and reputation management have been created. Federally, emergency protocols for tourism are non-existent.

Chafe said he isn’t surprised more hasn’t been done, given the scattered, fragile nature of an industry largely comprised of small, privately owned businesses that are represented by countless entities – non-profits, municipalities, visitor information centres, and tourism marketing organizations. Indigenous businesses, represented by Indigenous Tourism BC, add another layer of complexity, as many of the First Nations bands that own the tourism ventures have their own evacuations and emergency protocol.

Chafe was animated, pointing in various directions. “There’s no straight line of communication because everyone can work with Destination B.C., or with us, and we can work with them, and they can work across, or straight to the Ministry of Tourism. It’s all a tangled web,” he said. “We’re not well-represented because there’s no unified voice for us like there is for the forestry or mining industry […] The job I’m doing is the closest thing to a voice for a large region of businesses.”

A cademics have devoted little attention to efficient crisis communication in tourism. Instead, studies out of Oregon, Australia, and the Mediterranean assess the social and financial impacts that extreme weather events have had on their regions’ tourism industry. A 2008 study from south-east Australia suggests “clearer communication with the public,” “more proactive media liaising,” and, in general, more “forward recovery planning” for the future.

In Canada, a 2009 academic study titled A Lot of Concern but Little Action, claims a lack of coordination “between planning and marketing in most organizations,” and “between government and industry” during times of crisis. More recently, a 2018 Canadian literature review from the University of Waterloo, in Ontario, reveals a lack of knowledge on tourism’s “community-based impacts and adaptations to climate change,” particularly in B.C., where tourism is “fast-growing and very lucrative.”

The only disaster management framework for the industry in Canada was published in 2007, in response to the large-scale wildfire damage in 2003, near Kelowna. Dr. Peter Keller and his graduate student, Perry Hystad, who at the time were at the University of Victoria, proposed a complex system for tourism organizations, business, and emergency bodies, to communicate with each other during a disaster event.

“We shared the work with Tourism Kelowna, and for a while there was quite some interest there,” said Keller. Though a follow-up with Lisanne Ballantyne, the president of Tourism Kelowna, revealed she “hadn’t heard of Peter Keller’s paper.” Instead, she referenced a more recent set of crisis response guidelines her team uses, broken into four-levels of outreach, depending on the severity of the emergency.

Keller and Hystad moved into other areas of research after their study was completed. Keller said he hasn’t kept up with current developments in emergency management and hasn’t been consulted by anyone on his 2007 study. “The opportunity for research here is massive,” he said, noting tourism’s lack of preparedness.

Daniel Scott, a geography professor in Waterloo, and one of the world’s leading scholars in tourism climatology, has spent most of his career researching how tourism and climate interrelate. “There’s a dearth of academics in disaster management and tourism,” he said bluntly. “It’s incredible how you’ve got these events happening and we’re not in there dissecting them.”

C hafe calls his new job in Williams Lake “business continuity under a new label.” In June, he began arranging appointments for many of the region’s tourism operators – most of them rural, family-owned businesses – over south-central B.C., an area larger than Portugal. He said despite extreme weather events, many of them don’t yet fully understand the danger in wildfire. He discusses with them the likelihood of a disaster in their area and attempts to persuade them that precautions aren’t as strenuous as “setting up a two-kilometre-long fire line,” but a collection of small, manageable tweaks to their business operations.

Sitting in the boardroom, he held up a slim, blue government booklet titled Prepared BC, a guide for tourism operators, published with the help of the CCCTA. It suggests operators “pick a primary and secondary meeting place” for their guests, “plan for people with additional needs,” and train their staff, among other measures, for emergencies. A set of back-up supplies are pictured – a first-aid kit, a dust mask, garbage bags and personal sanitation products.

“But do you have 72-hours’ worth of food, and a flashlight tucked away in a bag in your house?” asked Chafe. “No. Nobody does. Right now, they’ve got a long list of other things to do, and an emergency plan will never get to the top.”

The apathy can fade, though, during the half-hour he sits with them. After all, Chafe does the “grunt work” by gathering information about their region and their business. He then tailors the plans to their specific needs: the bright-orange duo-tang replete with local phone numbers, emergency web-links, and an evacuation strategy.

“I find everyone through any means possible, be it the internet, the local tourism association, the visitor information centres. Because the region is so bloody huge, I can’t justify driving out to an area before I get a couple people on-board,” said Chafe.

Planning road trips to some of the distant communities isn’t the easiest task, though, as many of the ranchers isolated in the Chilcotin flat-lands aren’t as well-represented online. “We have a 500-kilometere-long highway with very little cell reception,” Chafe said, pointing to a massive map of the tourism region on the boardroom wall. A winding rural highway is seen spanning the half-width of the province, from Williams Lake to the coastal community of Bella Coola. “We’ve got people here who just don’t exist on the internet, and the population generally isn’t young, internet-savvy people. […] Some have been here for 60 years and rely on a sign on the side of the road for business.”

Map of south-central interior B.C. (Photo courtesy of the Cariboo-Chilcotin-Coast Tourism Association)

While the remote, wild-west wilderness is a tourist attraction in itself, Chafe said it means there are unclaimed Google listings, poorly constructed websites, little-to-no social media presence, which, in the digital age, isn’t conducive to circulating crucial information to the tourism community. These are the kinds of people who really need preparedness plans, he added.

Chafe also hopes to convince the social service teams at evacuation reception centres to accommodate tourists. Currently, their mandate is to help locals who have been evacuated from their homes find lodging and basic necessities. “In other words, tourists don’t exist in the system,” said Chafe. “Where do they go when everyone leaves?”

After the peak season, Chafe said he plans to arrange presentations on disaster response to groups of business owners at tourism-related events. His goal is to build a permanent database of the companies that exist, where they’re located, and what resources they can access, to improve communication during crises.

The idea for the project hatched well before the 2017 fires ravaged the Cariboo, said Amy Thacker, the association’s CEO. “We’d already responded to localized fires, and to some major flooding,” she explained. In 2014, the Cariboo suffered a horrific mine tailings pond dam breach at Mount Polley, just north-east of Williams Lake. Massive amounts of mining waste flooded into Polley Lake, which then entered the Cariboo river. “That was the first reputation-recovery campaign we had to run, and we learned from that,” said Thacker.

Chafe describes Thacker as a “total disaster nerd.” The daughter of a ranching family, Thacker grew up in various regions of B.C. and the Yukon and became the association’s CEO in 2010. “On day three of my job, part of the community was evacuated due to wildfire, so the emergency stuff became a passion for me right from the get-go,” she laughed.

Nothing could have prepared her team for the onslaught of 2017 though. The organization faced its own two-week evacuation, and still worked quickly to try to deliver the facts to tourism operators through websites, phone calls, and social media, and to combat the misleading news headlines. Much of the peak season was spent gathering and relaying information through daily conference calls with the local and provincial emergency operations centres, the information centre network and the government.

Amid the pandemonium was the abrupt realization that without any real structure or strategy, the industry could collapse for the year onward. Come August 2017, a hastily assembled sub-committee, chaired by Thacker, had formed out of the desperation. Members from the provincial government, two other regional associations, and the Tourism Industry Association of BC, convened to create an emergency reputation management sub-committee, to begin strategizing on a crisis protocol.

A report by the committee in June 2018 outlines a list of recommendations to integrate tourism further into disaster preparedness. Among them is the need to “ensure emergency response and communications plans are in place” for all provincial, regional, and local groups, and to “ensure visitors are included in these plans.” The list suggests joint training between the regional associations and the EOCs, and the need for proper internet connectivity and preparedness manuals.

As the hellish season simmered down, Thacker focused on wholehearted recovery. “No other region was as severely impacted as we were,” she said. Along with two other tourism regions, Thacker’s team was given $200,000 from the government for recovery marketing initiatives. The Ministry of Tourism also allotted over $500,000 to Destination BC to market the affected areas to the outside world and provided the Red Cross with $100-million to assist the small businesses in all affected industries.

Thacker, who’d been awarded a government grant to fund her long-anticipated emergency planning employee, seized the opportunity. The project would become a response to the list of recommendations her sub-committee was currently crafting, and one she and Chafe hope will set a precedent.

“Once we prove the concept here, the (government) will see that this is a thing that needs to be done,” said Chafe. To have tourism representatives across the province, that focus solely on emergency preparedness and media liaising, would cost a minuscule amount of money and very little effort from the powers that be, he added.

Finally, a possible seat for tourism at the disaster-response table.

Chapter 4

‘what we need is advocacy’

A smoke-ridden Helcmken Falls, in Wells Gray Provincial Park, B.C. (Adam van der Zwan, 2018)

Tay Briggs inhaled deeply, then exhaled. Her fingertips hovered over her office keyboard as she contemplated her words. The date on the email read July 21, 2017. She pressed delete and watched her sentence disappear before she tried again.

“Hi Jeff,” she typed. “In complete and utter frustration, I am forwarding you an email that represents a small slice of my daily life for the past two weeks.” She inhaled again. “My guests are upset and angry. They do not understand why on earth we are unable to be more informative on so large a topic as a complete park closure.”

Across the room, her lanky 20-year-old son, Boden, pressed send on another email to a bewildered customer. The crowded office, a small house-like building that once doubled as a classroom for Briggs’s home-schooled children, seemed to vibrate with a tension that might shimmy the folded maps, hand-held electronics, and science textbooks right off the shelves.

Today was the acrimonious breaking point after B.C. Parks, the government branch that manages provincial parks and protected areas, made a rapid call to close more than 540,000 square hectares of wilderness paradise, amid smoke that seemed to be sliding from all sides into the small town of Clearwater, on the central-eastern side of B.C. For Briggs and her husband, Ian Eakins, the sudden closure of Wells Gray Provincial Park meant their whole business, and the others in town that rely on the park for a collective $21 million in annual revenues, would go up in flames, even when no actual wildfires had infiltrated.

Tay Briggs, of Wells Gray Adventures (Adam van der Zwan, 2018)

The pair had raised their three children around the lush forests, glacier-fed lakes, and snow-capped mountains of Wells Gray. Every year, hundreds of thousands of tourists stop in Clearwater on the Yellowhead highway and make the northern 45-minute detour to the home of pristine waterfalls, including Helmcken Falls, one of Canada’s highest, and engulfed by an enormous layered rock canyon.

After 13 years of guided hiking in the Himalayas and New Zealand, Eakins was inspired to bring the experience home. Freshly married, he and Briggs, a local forester, pocketed their park permits and built a series of small backcountry huts in the mountains in 1988, for their new company Wells Gray Adventures. They filled them with food, books, bunk-beds, and boiled creek water, where their team of guides then brought tour groups on overnight treks through the natural world. The pair also signed contracts with wholesale tour companies to guide canoe excursions on the shimmering Clearwater Lake, at the end of the park road.

On July 9, the rhythm of summer slammed to a halt. Alongside Briggs and Eakins, a group of rafting, horse-back riding, guided hiking companies, and other park permit holders, were in utter shock as they were promptly cut off from their livelihoods with 10-hours’ notice.

“B.C. Parks called us in the evening the night before. We thought it was a joke. Are you kidding me?” said Eakins, on learning that a complete park closure had been ordered for 8 a.m. the next morning. He’s a slight man with a large personality, glasses and a receding hairline. “We had over 72 guests in the field,” he added.

Briggs was equally expressive. She fumed over the 24 teenagers who were forced to cut short their canoe trip. “All amount of reason went out the window. Not a single fire in the park, and these kids had driven up from the United States for four days on Clearwater Lake.” She described the next couple weeks of endless phone calls, customer frustration, and trip cancellations as “unprecedented” for the family-owned business that makes most of its income during the summer.

Earlier that spring, the couple had already spent thousands of dollars updating their chalets, buying food for their guests, and operating their vehicles. By the end of the summer, their small family-owned business would lose more than $66,000 to refunds for tourists, many of whom had reserved their vacations over a year in advance and were angry with the sparse contact they’d had on whether the park would re-open.

Briggs was equally desperate. She had already sent a number of exasperated emails to Jeff Leahy, the B.C. Parks Regional Director in charge of the closure, begging for communication and cooperation with the area’s tourism operators.

Briggs, who also operates the town’s Information Centre, was shocked to learn, two days after the closure, that Leahy had abruptly hung up on one of her staff members after hordes of oblivious tourists with questions had prompted a desperate phone call for updates.

She continued to type.

“…I can’t even get one straight answer from you or anyone else in [B.C.] Parks about what is going on. We call, we send emails and try in every way to get more information and we get almost nothing. Considering the financial and emotional stress this situation is putting on the town of Clearwater, I think the tourism operators deserve more consideration.”

Her fingers crafted the final blow. “As a result, our town is watching the good reputation we have built, and the relationships they are based on, be trampled on.”

She attached samples of incensed emails – customers “very frustrated with a lack of updates” needed to “plan [their] own lives” – and hit send.

(Adam van der Zwan, 2018)

The morning of July 8, a group of park maintenance trucks rolled up the park road and into the provincial campsites, where hundreds of tourists had pitched their tents or planted their RVs. Two days earlier, a lightning storm had sent parts of the Cariboo up in flames, and a small fire about 20 kilometres south of Clearwater was now beginning to drift northward along the opposite side of the North Thompson River. The problem was that wildfire could hop over the water.

Merlin Blackwell, who owns the local park maintenance company contracted by B.C. Parks, had been tipped off by the Parks team the day before. His team stopped at each site to inform the tourists of the possible order, and that they’d have at most an hour to pack their belongings and leave, should it occur. Blackwell, now the Mayor of Clearwater, said that within six hours his team had evacuated more than 1,500 people.

The official order was made that evening under the premise that the risk for wildfire in the park was too great with so few firefighting resources at the time. Late the next morning, the B.C. Parks rangers drove a government jeep 10 minutes north of town, to the Spahats Falls turn-off. This is the technical entrance to the park, though a large stretch of private properties lay further down the road, in a section not designated park land. They erected a barricade across the road, and the next few hours were what Blackwell described as “vile.”

“B.C. Parks ground-staff were treated incredibly poorly by a few prominent business-people in Clearwater,” he recalled. When tourism operators arrived, many of whom lived past the barricade and could not access their properties, a war of foul words ensued. Blackwell said he “watched one outfitter berate, argue, and belittle” the rangers. Words like “stupid,” “idiot,” and “moron,” among others, were thrown carelessly into the ether.

On the business side, if the Parks crew had placed their barricade 250 meters up the road, hundreds of tour busses would have still been able to visit Spahats Falls, one of the Park’s main attractions close to town.

Eakins recounted his anger at being denied access by a group of rangers who appeared no older than “19-years-old,” to a rack of boats he keeps at Clearwater Lake. “They were reveling in the fact that they could make peoples’ lives miserable,” he said. After a rancorous back-and-forth, the rangers agreed to escort him for one hour, which Eakins argued wasn’t enough time to retrieve 28 boats.

While Jeff Leahy refused to be interviewed for this story, Dave Merritt, the B.C. Parks Incident Commander hired to manage the closure on-site, said bullying at the barricade “happened quite regularly.” When the complaints were later re-directed to Merritt, he told business owners that the park was closed “full stop.” “We couldn’t let somebody in when we didn’t know where they would go,” he explained. “Our responsibility is to ensure public safety, and that the park is safe.”

The town of Clearwater sits south of the entrance to Wells Gray Provincial Park. (Photo courtesy of Google Maps)

B riggs and Eakins were left to concoct others trips that would satisfy their guests and honour their contracts. They rented a boat launch at Blue River, over an hour up the highway, where they spent a costly three days clearing an overgrown trail.

At one point, Briggs was floored when a representative from Destination B.C. called her to ask for a list of tour companies that visit the area, so they could be notified to cancel their trips. “I told them they need to get their facts straight,” Briggs described. “There are no fires here, and there are a lot of families suffering badly.” She said the representative from Destination B.C. was receptive enough to listen when she explained the situation.

On July 14, Briggs sent a Modified Access Plan she’d devised to the municipality and B.C. Parks. “If we are to have a tourism industry, ways must be found to manage visitor access during high fire hazards,” it read, imploring the decision-makers to “draw on the expertise” of the locals to “ensure public safety” and “keep the tourism industry moving.” Included in the plan were provisions for proper communication between all stakeholders, for “guided-only access to Wells Gray” during an extreme hazard, and public access only to the road-side waterfalls during lower hazard periods.

The B.C. Parks team, who were then re-writing the park’s evacuation plan for the first time since 1986, requested that she elaborate on the resources her company would have during extreme weather events. Briggs responded with the evacuation routes from her huts, and her guides’ qualifications. “Wells Gray Adventures has had 110 multi-day bookings canceled as of today,” her email included. “If we are unable to give any assurances to our other customers by tomorrow, we will lose the bulk of our summer season.”

On July 25, B.C. Parks relented and re-opened Wells Gray, though Briggs said the Information Centre wasn’t notified. “By then we’d cancelled most of our trips,” she said in exasperation. In disbelief, she, Eakins and their son began a desperate marketing push, spending money on extra Facebook advertising, sending out emails and making phone calls to salvage the last of their cancellations. Not two weeks later, Leahy once again called for a “partial closure” of the Park, as the surrounding fires took another turn once again toward the area. This time, though, the tourism operators were allowed special permits into the backcountry where they could continue their guided trips.

By the end of the summer, Briggs realized that the relationship she thought the tourism industry had with B.C. Parks didn’t really exist – and she was devastated. “There’s a fundamental disconnect between how government personnel look at parks management and wild lands, and how the people who use them look at it,” she explained. She hopes for collaborative approaches to disaster management between the public and the private tourism sectors – ones based on frequent communication and a mutual understanding for each other’s aims.

For years, she’s tried to foster these kinds of relationships by remaining calm, patient and as respectful as she can be with local and provincial governments, she said.

Currently, B.C. Parks’ official mandate includes “the requirement to maintain a balance between […] goals for protecting natural environments and outdoor recreation,” though it doesn’t address any responsibility for the economic potential and activities that are linked to the parks. Briggs said the local economy should be included in their management models more than they have been.

Blackwell agreed. “If it were run more like B.C. Ferries, [a provincial Crown corporation] the benefits would be massive for communities,” he claimed.

When asked about an obligation to help the tourism industry during wildfire risk, Merritt spoke firmly, suggesting business owners buy the proper insurance. “Let me spin the question around on you,” he began over the phone. “If your business is based on one model only, who’s responsibility is that? […] What if it did burn? Is it my responsibility to rebuild your building? Your reputation? How would we be responsible for that? We’re trying to ensure the public has access to this park in the long-run.”

As the small fire south of Clearwater edged closer up the river, Stephanie Molina said she “went into crisis mode” behind her desk at the town’s community centre. The marketing manager for Tourism Wells Gray, a local organization funded by the province and governed by a 12-person volunteer board, Molina said her role in “sharing information to the [local] businesses” was crucial.

In contact with the municipality and the B.C. Parks team, she buckled down on the phone lines to ask local outfitters what alternate attractions they could offer outside the park. “We created an entire list of the opportunities and circulated it to the accommodations in town. It was on our website, on social media, and was sent out to the information centres,” she described with careful sentences.

The major frustrations arose at the start of July, when “negative messaging” seemed to surface everywhere in the news. Journalists in all media were effectively discouraging the public from entering the smoke-ridden, but otherwise fire-free park. While Destination B.C. and the regional Thompson-Okanagan Tourism Association (TOTA) pushed wider, regional campaigns, Molina published news releases to advertise Wells Gray and “dispel the myths” about its closure.

In August, after the Park had closed again to all but the guided tour groups, Molina said she worked to combat the discouraging “partial closure” phrase that permeated government releases and was electronically emblazoned on the large signs rooted at the park entrance. In marketing language, the proper words are “limited access.”

In the aftermath of 2017, Tourism Wells Gray received $15,000 in marketing money from Community Futures, a non-profit aimed at helping small Canadian businesses, and $7,000 from the Red Cross, which was used the past year for an off-season pilot project – the Winter Waterfall Tour.

A B.C. Parks barricade on the Wells Gray Park road. (Adam van der Zwan, 2018)

A scroll through Tourism Wells Gray’s Facebook page last winter flashed videos of an enormous, immaculate waterfall shrouded in snow. The freezing temperatures have formed a light-blue volcano of ice on the cave’s floor, where the whitewater tumbles through the top. “Smoke has really impacted tourism numbers. […] We’re seeing more visitation during the shoulder seasons,” Molina explained. Opening the waterfalls during winter has always been on her radar, but the excessive smoke in 2017 and 2018 had “added a sense of urgency” to the project.

Other questions have surfaced on whether wildfire, itself, should now be marketed, though Molina said the advertisements for Wells Gray still exclude this messaging. “Are we looking to attract attention to that and conflate our brand with the idea of wildfire?” she asked.

To market extreme weather is less unusual now than it once was, as some companies in Western Canada have taken to explaining the earth’s ‘natural processes.’ The 2018 edition of Experience the Mountain Parks, a widely distributed travel guide for Western Canada, opens with a section on the 2017 wildfires, complete with images of firefighting crews and swaths of blackened forest. “Visitors are naturally concerned,” it reads, but “the first priority [of wildfire crews] is the safety of the public and infrastructure.” Bob Harris, the travel guide’s publisher, explained that to offer readers a “balanced and informed perspective” would lessen confusion and fear toward future weather disasters.

In Clearwater, Tay Briggs said the future isn’t just about changing the industry’s approaches to marketing, but about advocating for an industry she feels is “severely undervalued by the B.C. government.” “You’re stacking a bunch of mom and pop businesses up against resource-based industries like mining – corporations with pull and money and lawyers. We need some real collaboration,” she explained.

The lack of advocacy is palpable among the locals, she said, recalling a letter she’d written to the province’s Ministry of Tourism, on August 31, 2017. “We need help,” it pleaded. “We must find ways to allow economic activity in the areas where it is possible.” The letter was co-signed by 30 of the town’s tourism operators. “I’m stunned at how many people will sign something like this, but write their own? Only a bare handful. All these little businesses think they’re standing alone,” said Briggs, reflecting on the locals who seemed hesitant to speak out even after she’d contacted them.

A wildfire impact report, produced by the TOTA, says Clearwater, Wells Gray, and the rest of the tourism region lost in total $86 million in 2017, and another $20.6 million in 2018.

“You can make brochures, you can advertise things, but now we need a representative that’s a cohesive unit […] to advocate for us to the larger entities that don’t understand us, (and) become a force for an industry with a say in land-use policy,” said Briggs. “We have to.”

(Adam van der Zwan, 2018)

Chapter 5

‘I’m not leaving’

Hat Creek Ranch, near Cache Creek, B.C. (Adam van der Zwan, 2018)

Don Pearse watched two exhilarated families decorate an historic gold rush orchard, for a wedding to be held that weekend. With heartfelt anticipation, they strung the banners, propped up the wedding tents and splayed out the dining tables they’d rented. An excited bustle of bodies zipping over the grass, that Thursday afternoon on July 6, 2017. Pearse was uneasy, however. It was 3 p.m. and when he peered south at the horizon, he could now see a wall of flame cresting over the mountaintops.

The wind was blowing north, and the fire that had sprung from a lightning storm near Elephant Hill Provincial Park that morning was now swelling towards them. It was 20 kilometres away.

Pearse described the line of fire as “probably 100 feet in the air. It was spectacular but it was pretty scary at the same time.” A swarm of grey smoke resembling an air-borne mold floated toward Hat Creek Ranch, the provincial heritage site Pearse operates on ranch lands west of Kamloops. His unease became unbridled anxiety for the people and historical buildings that surrounded him.

The Ranch, owned and partly funded by the government’s Heritage Branch, is one of the historical jewels of B.C.’s southern interior, Pearse explained. At the intersection of two prominent highways, Hat Creek boasts the gold rush experience, coloured by actors in period clothing, stagecoach tours, gold-panning troughs, an Indigenous interpretive site, and a restaurant. The property sits on the original Caribou wagon road travelled by miners and traders in the mid-19th century and was established by Hudson’s Bay Company’s chief fur trader Don MacLean, in 1860. Today, the ranch is a step into the past, like Barkerville but smaller in scale.

For Pearse, too much was at stake. He approached the wedding party and advised them to pack their things, but it took some convincing. “The younger ones were all pumped up – ‘We’ll live through this,’” he impersonated. Later that afternoon when the fire had advanced, the fathers of the bride and the groom approached him with honest concerns.

“What do you really think?” they asked. “I think you need to leave right now,” Pearse answered.

The families left immediately. A wedding display completed, then simply abandoned. Pearse then asked his 36-person staff of actors, restaurant servers, and maintenance workers to return home. Many lived toward the fire in the town of Cache Creek, which was now under evacuation alert, while a few stayed at the ranch overnight where they’d bunked for the summer.

Don Pearse (Adam van der Zwan, 2018)

Pearse is a pleasant, social man with a sincere smile and easy laughter. Often, he can be found mingling on the restaurant’s patio with his visitors, many of whom he says are recurring. He’s worked in managerial roles at Hat Creek for the past nine years.

After finding the job posting as “a fluke,” he saw it as a career to replace his “highly demanding” position as vice-president of a construction supply company in Washington. While Hat Creek’s tourist season spans from early May to late September, Pearse and a roommate live in a quaint house near the parking lot year-round. He maintains the property, tends to the farm animals and works on construction projects with whatever government grants he can secure.

The morning after his staff left, flecks of fire could be seen moving northward on the hillside across the highway, a dry face of bunchgrass and small clusters of trees, like in the rest of the valley. Pearse maintains that no fire has ever come as close to the heritage site as the Elephant Hill wildfire.

It began in a town called Ashcroft, just south of Cache Creek, where it ripped through a collection of homes in a First Nations reserve. The next day, the massive fire travelled northward to Boston Flats where it reduced an entire mobile home park to charred remains and burnt out vehicles.

Hat Creek Ranch sits north of Cache Creek, at the intersection of highways 99 and 97. (Google Maps)

By the evening of July 8, the town of Cache Creek was evacuated with over 1,000 people forced from their homes after the fire had grown northward from 700 to 4,000 hectares in about five hours. The police then knocked on Pearse’s door and issued the order. Pearse drove an RV four kilometres east toward Kamloops and planted himself at a friend’s ranch, where he could easily drive back every couple of days to feed the animals, with special permission from the province.

On July 20, nearly two weeks after the order, the police arrived at the ranch where Pearse was camped to inform him they’d be lifting the order that day, and to offer him early permission to return to Hat Creek. When he arrived, though, the police stationed near his property were confused and denied him access, claiming no plans to lift the evacuation.

Angered, Pearse parked his RV on the north side of the highway next to Hat Creek, where the order wasn’t in effect. Then, disregarding the police, he walked across the street to his house and stayed there.

Wildfire cripples the hillsides across the highway from Hat Creek Ranch. (Don Pearse, 2017)

The evacuation order lifted that evening, and Pearse and his staff spent the next couple days vigorously cleaning the buildings, though business for the coming week was nearly non-existent as thick smoke and ash filled the air. Pearse recounted a handful of bus tours that stopped in.

Tour buses comprise the majority of Pearse’s customer base – he sees more than 400 annually, each filled with tourists from all over the world, who typically spend the afternoon at Hat Creek. But this time “they weren’t sticking around,” he said. “[The tour guides] were nervous about the fires returning, and about the air quality. It wasn’t a nice place to be.”

The evening of August 4, 2017, the unthinkable occurred. Hat Creek received another evacuation order as the wildfire, now over 100,000 hectares, had jumped the northbound highway and, with the sudden winds, was moving south toward the ranch. The police arrived with flashlights in the night and ordered Pearse to evacuate.

“I’m not leaving,” Pearse retorted. His roommate agreed, as did a friend who’d been camping in Pearse’s RV after having fled her home at Loon Lake, which was now consumed by fire. Once again, Pearse asked his staff to leave, and was then told by police that he would be allowed to stay on the condition that he not leave the property. If he did, he’d be barred from returning.

Pearse obliged, and the three set to work rigging a sprinkler system and preparing food and drinks for the fire crews who, this time, had stationed themselves on the grass and in the parking lot. Alongside fourteen fire trucks were seven helicopters that were taking off and landing within the fence. “We have a 250,000-gallon sunken water reservoir here,” said Pearse. “It’s designated for fire, so [fire crews] were able to fill up just like they would from the hydrants in the city.”

Firetrucks scour the property at Hat Creek Ranch. (Don Pearse, 2017)

Collectively, up to 700 firefighters battled the Elephant Hill blaze for another 12 days before the evacuation order was finally reduced to an alert. By then, the fire had grown to 170,000 hectares, but had receded on the Hat Creek side of the highway. Nearing the end of peak season, the financial loss had been devastating for a ranch that Pearse said is already strapped for resources, being a government-owned property. Hat Creek’s financial documents show nearly $200,000 in cancellations – a quarter of its annual revenue – which doesn’t include the loss of a large quantity of food, and the labour that Pearse paid for the sprinkler system. But the frustration didn’t end there.

Helicopters took advantage of the large water reservoir on the ranch’s property. (Don Pearse, 2017)

Later that year, Pearse sent his financial losses to Richard Linzey, the director of the province’s Heritage Branch, to request extra recovery funding. “They refused,” said Pearse, visibly uptight. He was especially angry after the Heritage Branch had instead given Barkerville – another provincial heritage property of the same standing – more than $700,000 in recovery funding after 2017.

“Barkerville is a very strong lobbyist with the government,” he claimed. “They have a lot of pull. They’re a big entity. But they didn’t have to close during [the 2017] wildfires like we did.” Pearse said he hasn’t received a proper explanation from Linzey nor Roger Tinney, the stewardship manager who communicates with the site operators, on why Hat Creek hasn’t been granted extra money. Instead, his emails are “stonewalled” or “pushed off” to other people.

When asked about the funding decision, Richard Linzey was straightforward. “Barkerville has a huge staff, and they had to make a difficult judgement call on whether to close and lay everyone off, or to keep it open,” Linzey said. They chose to stay open. After the 2017 fires, Linzey clarifies that Barkerville lost more than $700,000 in revenue, and the town’s board of directors had forecast too few visitors in 2018 to pay the money needed to keep the whole staff. Hat Creek Ranch’s financial account, Linzey explained, “didn’t show them being out-of-pocket. They were still able to manage with their own resources.”

Both heritage sites belong to a group of 19 that are wholly owned by the provincial government and allotted a certain amount of money each year. When extreme weather events occur, Linzey said he typically sees an increase in requests from site managers for repair funding. A limited amount of money from a reserved operating budget is then triaged to the sites that need it the most. Barkerville, being so large and surrounded by densely forested hillsides, is extremely susceptible to wildfire.

Linzey revealed, however, that the summer’s aftermath was a “learning experience” for the Heritage Branch. “We need to be thinking holistically about all of our sites’ assets,” he admitted. “We need to have a more transparent and measurable process with our site managers on how we make [our funding] decisions going forward.”

Barkerville’s history of wildfire dates back to September 16, 1868, when a massive fire erupted from the town’s saloon, after a miner knocked himself against a stovepipe in attempting to kiss a saloon girl. Frederic Dally, a town photographer at the time, details the event in the only known first-hand account of the disaster – a period when the townspeople had a “settled opinion that the wood the town was built of was different to other wood and that it would not burn.”

“Although my building was nearly fifty yards away,” Dally writes, “in less than twenty minutes” […] the town was a “sheet of fire, hissing, crackling and roaring furiously.” The fire then caught on the trees up the mountain ridge, a scene that, when the sun went down, “will not be quickly forgotten.” Today, Ed Coleman, the CEO of Barkerville, said he’s still working on a proper fire protection plan to treat the town’s preserved wooden buildings.

Ed Coleman stands in front of Barkerville’s main street. (Adam van der Zwan, 2018)

“We had a good, solid three-day assessment of our risks” in July 2017, said Coleman. He’s an amiable, practical man, with a measured demeanour and a background in computer science. “If a fire got too close to us,” he explained, “we’d have six fire departments here from all over western Canada, and they’d be soaking the place down.” He said small skimmer airplanes and helicopters would drop water on the hillsides, and the focus would become “24-hour protection.” Coleman’s maintenance staff would also ensure the logging roads that serve as evacuation routes would be clear of fallen trees.

In 2018, Coleman said business has increased somewhat steadily from the prior year, despite the thick mid-August smoke, and the continued threat of wildfire. Over the years, he’d noticed a change in the weather – the winters are warmer with shrinking levels of snowpack, and the rain isn’t as frequent. “The forest floor is dryer,” he noted. “That’s a fundamental shift.” Linzey said the Heritage Branch plans to develop an “effective and affordable” protection plan for the town, which will increase the town’s water supply by refurbishing one of its old water tanks.

Since Coleman became the CEO five years ago, he’s been working to treat the forests by “de-limbing” the bottom 12 feet of the trees around the town, though the process is costly. “A hectare can cost you anywhere from $2,500 to $6,000, depending on whether it’s on a slope, or how many dead trees are in the way,” he said, adding that he still has to treat about 500 hectares, but the funding is only in place to treat the first 52. At this point, curing the Barkerville forests could take years to complete.

I n early August 2018, Don Pearse held a special dinner for his staff in the Hat Creek Restaurant, a characteristically rustic space with wooded accents and paintings of horse-drawn carriages on the walls. “You could see their spirits rising,” he recalled. The room filled with “laughs, lots of jeering and good-hearted fun.” He arranged a gift swap for his employees, with everything from bird feeders and camping chairs to towels and tool sets – trying to boost the staff morale after what had been another difficult season.

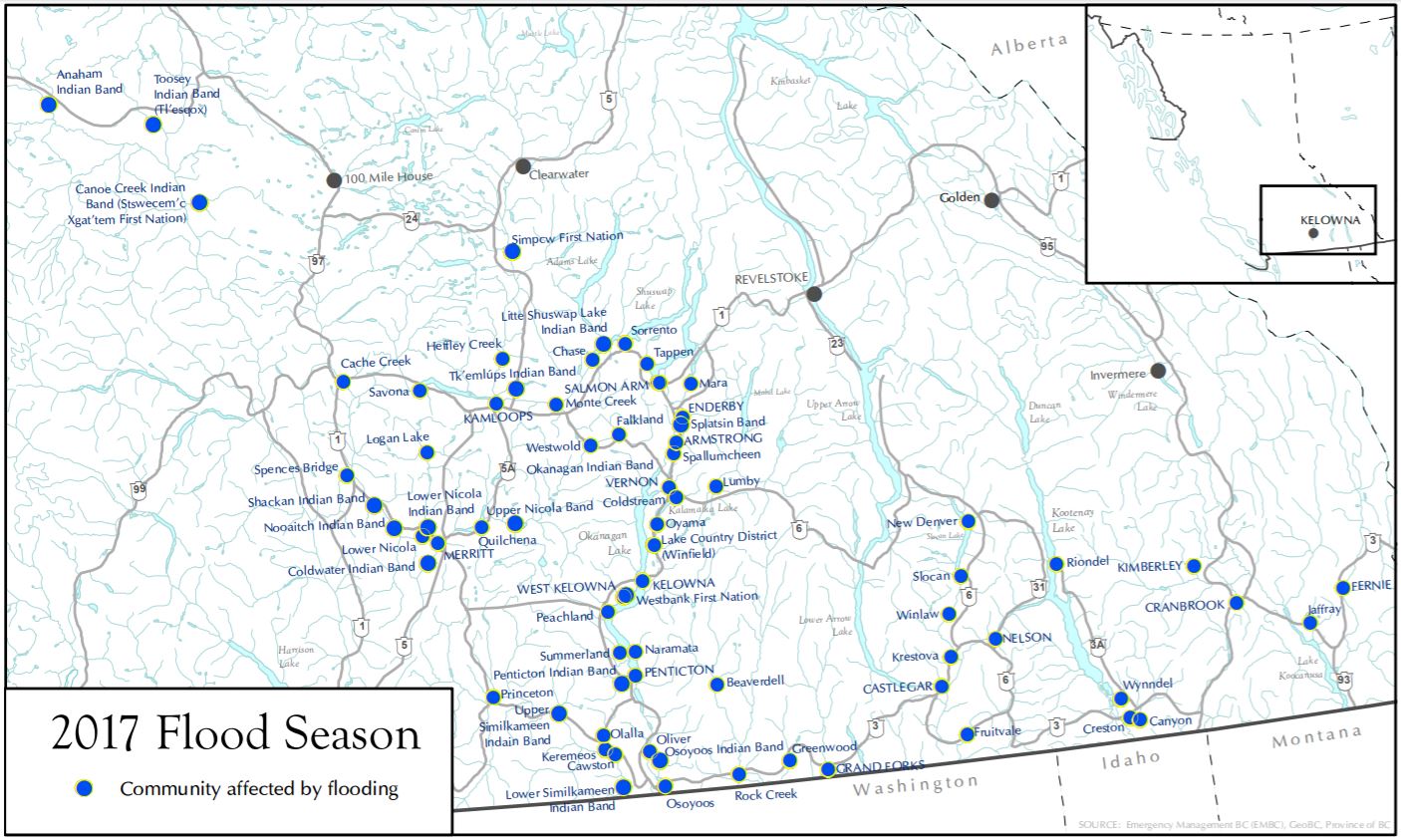

In early April 2018, large-scale flooding swept through Cache Creek, damaging roads and multiple buildings. The town declared a state of local emergency and more than 100 workers gathered to haul sandbags along the creek sides and properties. Pearse speculated on the wildfires having increased the flooding after burning through the trees and brush that would normally hold the freshet and snowpack together.

B.C. has witnessed terrible flooding the past couple years. The Abbot-Chapman fire and flood review states that 2017 was a year of “record-setting freshet flooding,” as dozens of low-lying communities in the Okanagan, Kootenay and Shuswap regions were affected, in the south-central interior. The floods resulted in “forced evacuations” […] “damaged homes and infrastructure,” and an estimated $73 million in flood response, the report says.

In 2018, large-scale flooding returned along the rivers in south-eastern B.C., pummeling towns including Grand Forks, where the Canadian military intervened to help save the devastated area.

(Source: BC Wildfire and Flood Review, 2017)

After the flooding came the mudslides, said a defeated Pearse. The thick smoke that had settled in early August, 2018, was briefly interrupted by a violent rain and thunderstorm, causing a slew of mudslides near the ranch, along the intersection of both highways in the area. Along the west-bound highway, 17 landslides came tumbling down a small stretch of the hillside. The boulders and debris blasted over the road and swept away a 67-year-old woman in an old yellow convertible. Parts of the vehicle were located but her body has yet to be found.