Chapter 2:

Ben

He promised himself long ago he’d do whatever it took to get there.

We’re sitting in a City Centre food court – me nursing a coffee and Ben taking advantage of the bottomless orange pop and McDonald’s Egg McMuffin – and it’s all he can talk about.

“I’m going to be a cop,” said Ben, as he pushes his permanently smudged, wired glasses up his nose and wipes his face with a brown food court napkin.

“I’m going to get huge muscles,” he said. “That’s why I work out three times a week. That, and so I can look good for my girlfriend,” he added, as pink spots formed on his cheeks.

I ask him why he wants to work in such a dangerous profession.

“To help people,” he said, giving me a “don’t be stupid” look, before getting up to refill his drink.

As he’s walking back to the table, he stops and stares at two security guards, his eyes following as they slowly make their way through the tables and out into the mall.

He sits back down, his big 6’3” frame contorting to fit under the table, and is quiet. A change from the past week we’ve spent together. I’m about to suggest we head back home when he clears his throat.

“I wasn’t protected,” he said, his eyes trained on the older couple sitting beside us. “My parents never protected me from anything.”

Benjamin Minor, like most 26 year-old men in Canada, has dreams and ambitions. He’s got sandy blonde hair, and a smile stitched to his face. Ben dresses to impress; he’s either the cool guy with the faded jeans and brown leather jacket, or the business man with the button up suit and tie. Just like everyone else, Ben is trying to find his way in the world.

But Ben has Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder.

What is FASD

Ben is one of a suspected 50,100 people diagnosed with FASD in Alberta. Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder – or FASD – is a complex neurodevelopmental disorder that occurs with prenatal exposure to alcohol. It’s the most common neurodevelopmental disorder yet is the most misunderstood – it is often considered the hidden disability.

Children prenatally exposed to alcohol often display diffuse brain damage, meaning damage is widespread and can impact any structure within the brain. This can explain the large variety of symptoms and effects that can include multiple physical, behavioural, mental and learning disabilities, all with lifelong implications.

FASD is identified by abnormal facial features (like small eyes and a thin upper lip), central nervous system problems, (affecting areas like executive functioning – which help you manage life tasks of all types like organizing trips, researching a project, or writing a paper – memory, social and behavioural skills), and slowness of growth (both weight and height). It can cause physical and mental disabilities varying in severity. Because it’s not easy to recognize, individuals and families struggle to find access to the kind of lifelong support they need to be successful.

Alcohol can impact the fetus at any time during the pregnancy; harm can even occur before a woman knows she is pregnant. Because alcohol is a water-soluble teratogen – any agent that can disturb the development of an embryo or fetus – once consumed, it freely enters the fetus’ bloodstream. Since it takes longer for alcohol to leave a fetus’ system than an adult’s body, its effects are devastating and magnified.

There are many factors that determine the fetus’ likelihood of being affected by alcohol: like the stage of pregnancy in which alcohol is consumed; the amount of alcohol consumed; the frequency of consumption; metabolism and genetics. These can impact the fetus at any stage of development.

Paul Pringle, one of the leaders in FASD education in the community, said people need to realize that an FASD diagnosis doesn’t have to be a damaging life sentence.

“People with FASD are capable,” he noted. “It’s when we fail to accommodate that we create the disability.” He said people need to be accepting of the realities of FASD and understand that behaviour is a result of damage to the brain’s nervous system.

Historical timeline of FASD

High risk individuals

According to data from FASWorld, a global organization founded in Canada that provides support and education on FASD, 80 per cent of individuals with FASD cannot function without constant support, due to difficulties arising from both primary disabilities (disabilities a person is born with that will stay with them throughout their lifetime) and tertiary conditions (conditions a person is not born with that can be improved or prevented with better understanding and intervention).

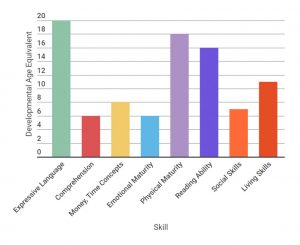

Many negative instances that occur throughout their lives are hidden symptoms that affect daily living activities. A person with FASD will have difficulties in areas such as attention, language, life skills, reasoning, memory, executive functioning, regulation of body functions and sensory issues; these are not visual disabilities. There is a disconnect between chronological and developmental age, which is why so many people with FASD are misunderstood.

Developmental versus chronological age for an 18 year-old with FAS

An adult with FASD has difficulties with money and time management; they may spend their entire pay check in one day or give it all to a friend, and they fail to understand the importance of adhering to a work schedule or following through with things such as a doctor’s appointment.

They can have a low level of emotional maturity, so often they are quick to anger and turn to violence during disagreements or stressful situations.

Their social and living skills aren’t developed, meaning they sometimes don’t grasp personal boundaries and social cues, or they don’t understand why it’s important to shower and clean on a regular basis.

Statistics from FASWorld state that 70 per cent of this population have problems with employment, 68 per cent of children with FASD have problems with school and 52 per cent will exhibit inappropriate sexual behaviour. Sixty-eight per cent will have trouble with the law.

Further, 95 per cent of this population suffer from other mental health problems. It’s believed the fetus’ brain vulnerability during development and the FASD population’s susceptibility to life stressors and high-risk social situations like homelessness, abusive relationships and addictions are contributing factors. Some of the multi-diagnoses include bipolar disorder, hoarding tendencies, depression and schizophrenia.

Access to lifelong supports – like they would get in a supportive housing model such as Melcor – is vital to their quality of life, according to Liza Rogozinsky, network coordinator with the Edmonton and area Fetal Alcohol Network Society. It’s a grassroots organization – made up of 45 different community agencies, governmental departments and advocates – that’s leading the area in FASD policy and education.

“It’s when things are closed that bad things happen.”

According to the Bissell Centre, the total annual costs of FASD in Alberta are $927.5 million; each lifetime cost per person with FASD is $1.8 million. Extrapolating from those numbers, the estimated annual cost per person with FASD is $300,000. These costs include things from emergency supports like ambulance and services, incarceration costs, medical costs and hospital stays.

Lasha Roberts, manager of community supports with the Skills Society, said adequately supporting that same individual with funding from the government would cost less than a third of that.

Due to confidentiality, the Skills Society was unable to disclose how much less it cost to fund a client who is in affordable housing versus someone who is either institutionalized or using emergency services and shelters. But Roberts said they need 75 per cent less in financial funding for Ben since he has lived at Melcor.

One day Reid was helping Ben clean his apartment. She opened a kitchen drawer to find bottles and boxes of unused medical pills prescribed as a mood stabilizer. Ben didn’t want to take them. Since then, he’s switched to medical injections, which work just like the pills. Once a month, either Reid or another member of the support team picks him up and drives him to his injection appointment.

Reid said Ben’s blossoming at Melcor. There’s a whole other side to Benny, she said, and we’re finally getting to see that.

Diagnosis

Ben has an official diagnosis, which means he is eligible for disability funding from various government streams. Because many mothers don’t admit to drinking while pregnant, there are many suspected cases of FASD; people who are only suspected often don’t have access to the same agencies and support systems.

Doctor Valerie Massey is part of an FASD diagnostic team in Alberta – D-V Massey & Associates – which is a private clinic in Edmonton. She said what sets them apart from other diagnostic settings is the fact they aren’t operating in a hospital setting. Many clients who seek out a diagnosis have been institutionalized – either incarcerated or in a residential school – and hospitals are often triggers for a traumatic past so they have a hard time being in a hospital. Having a community-based assessment process, in a familiar and comforting environment, makes sense for their adult clients. Further, they have more flexibility as a private practice, meaning they can easily travel to locations for assessments and accommodate needs for an emergency diagnosis (which is often the case in legal and correctional situations). They also have less of a wait time for a diagnosis since they can do their assessments anywhere, which is essential when they’re asked to do an assessment for someone who is on trial (many of their clients are referrals from the judicial system).

At $6000 per assessment at Massey’s clinic, it’s not cheap, but she said the benefits of a diagnosis far outweigh the costs of trying to navigate a high-risk lifestyle without adequate supports and services that come with a diagnosis.

There are different reasons why a diagnosis strongly benefits the individual. First, it can provide an explanation for what looks like inexplicable behaviour if someone is before the court. A high population – depending on who you talk to it’s anywhere from 50 to 70 per cent – of the incarcerated population has FASD; these individuals have difficulties processing cause and effect, and are often exploited by friends and family for their willingness to trust. They often have difficulties grasping subtleties and processing information too – they don’t understand what they are doing is illegal or high risk, and that can come off as a lack of remorse. Pringle says incarceration is based on two principles, deterrence and rehabilitation, and the system assumes the offenders can understand the nature and consequences of bad behaviour and thus change their behaviour, so there isn’t a repeat experience.

“Children are viewed as victims of birth defects and adults in corrections are viewed as deviants who have violated social norms,” said Pringle. Cause and effect reasoning won’t work on someone with brain damage.

Second, when before the courts, an FASD diagnosis can influence where a person is placed within the correctional systems. These people need a setting that can provide them with structure and support, where they are not easily influenced and manipulated. Massey points to a correctional facility in Saskatoon where staff members are trained in organic brain damage and are available to provide more directed disability support.

Third, a diagnosis means they aren’t perceived as lazy for not working. A disability diagnosis will help in providing disability support, which gives them a level of income stability that can translate to other aspects of life. It can also give them access to medical and dental coverage. Often adults with FASD have other medical issues, such as kidney failure and Hepatitis C, due to the fact they have lived marginalized lifestyles.

“They have really tragic short lives because they aren’t healthy enough and don’t know how to access the medical system,” said Massey. A diagnosis helps facilitate that access.

Because FASD is a complex neurodevelopmental issue, it takes correct training and skill to diagnose, and for Massey, that training and expertise boils down to asking the right questions.

“It’s a powerful diagnosis,” said Massey. “You have to have a sense of how important it is, and how important it is to get it right.”

The whole process can take a day and a half, after which the client will leave with written documentation – there is no wait for confirmation.

The client first spends five to six hours with Massey so she can assess brain function, cause and effect reasoning, motor function and executive skills, among other things. From there she comes up with a brain rank based on a four-digit diagnostic test, a universal, zero-to-four ranking used to come up an FASD diagnosis.

The four-digit diagnostic test evaluates the person in four categories: growth, face, brain and alcohol exposure. Growth deficiency in height and/or weight is assessed either pre or postnatally; specific patterns of facial anomalies like short eyes slits, a smooth philtrum (the ridges running vertically between the nose and lips) and a thin upper lip are tracked; brain damage to the central nervous system that includes things like tremors, hyperactivity, attentional deficits and intellectual impairments are considered; and alcohol use by the mother during pregnancy is confirmed. Since it is sometimes impossible to receive a mother’s confirmation, Massey relies on reliable third party information, such as data from families and communities, to confirm prenatal drinking.

The client then spends an additional two to three hours with a physician who conducts additional interviews and medical examinations to rule out any other potential causes for the symptoms, and to get facial and body measurements. After a debriefing with all involved in the diagnostic process, the client is provided with written documentation declaring either an official FASD diagnosis or otherwise.

AISH

It’s Tuesday, and it’s pay day. That means Ben gets $25, which, for this week, means laundry.

He’d much prefer a trip to Galaxyland to ride the roller coasters, but that can’t happen all the time. Most of the money – he also gets $50 on Fridays – goes to things like his electricity, cell phone bills, and groceries.

Because of Ben’s diagnosis, he qualifies for AISH – Assured Income for the Severely Handicapped – which provides financial and health benefits to eligible individuals in Alberta with a disability. Ben gets $1588 a month. It’s impossible to get rich on disability income, but Alberta is ahead of the curve in terms of disability funding. British Columbia gives just over $1000 for qualified individuals, for example.

Ben’s money is distributed through the funding administration program; an administrator assigned to his case file helps with his financials. His rent, at just over $800 per month, is paid directly through that, and with what’s left, he gets $200 a month strictly for groceries, $25 every Tuesday and $50 every Friday.