Chapter 5:

AnalysisHousing Models

Melcor isn’t the first housing project in Edmonton aimed at providing housing for those that need support. The Bissell Centre – an agency and outreach centre in inner city Edmonton – started Hope Terrace, a permanent supportive housing model for high risk adults with FASD. According to the Edmonton and area Fetal Alcohol Network Society, it’s the second of its kind in Canada that offers “specific housing support to a population that has a tendency to slip through the cracks.” But for Lasha Roberts, Skills Society community supports manager, a program that houses only one segment of the population isn’t always the best way to go.

“The segregation is marginalizing,” said Roberts. Because of their behavioural symptoms, like the inability to reason and understand cause and effect, if you put people with FASD together, they are vulnerable and easily influenced. And you end up labelling an entire group of people. That’s why the Melcor model is a step in the right direction, said Roberts. It’s the “whole idea of being a part of something else.”

Ideally, the Skills Society would like to try another model of housing where their clients live among people who don’t need support or subsidized housing, but in the end, it comes down to having a building willing to take on the individuals they support. And at the time, Melcor was the only building willing to give the partnership a try.

According to Deborah Steinstra, professor at the University of Manitoba and frequent speaker on accessibility and inclusion, a completely inclusive society means there is no longer a desire to segregate individuals who need access to support and resources.

The stigma around affordable housing is shifting, she said, solely because the population so vocal about the issue previously is getting older and realizing they need access to those same resources they criticized.

Prevention:

The irony behind FASD is even though it is an incurable, lifelong disability, it is completely preventable.

Fifty per cent of pregnancies are unplanned, yet 90 per cent of women admit to drinking during childbearing age. Nine per cent of Alberta woman reported drinking during their last pregnancy, and that number jumps to 41 per cent for women in the highest income bracket.

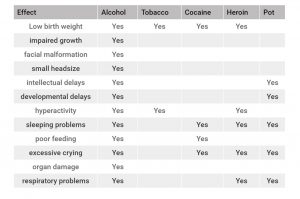

Alcohol is a societal issue; it plays an enormous part in our cultural experience, yet alcohol is proven more damaging to the fetus than other hard drugs like heroin.

Prenatal alcohol/drug consumption on fetus development

It’s a shared experience; it’s relatable, it’s common, it brings people together. And alcohol doesn’t discriminate – anyone who drinks during pregnancy can be impacted.

Dr. Valerie Massey, one of the top FASD diagnosticians in Canada, is working on increasing awareness about the impact of alcohol not just on the fetus, but on families and whole communities.

People now know it’s bad for your health to smoke cigarettes, they know they are supposed to put on your seatbelt, but because alcohol is so entrenched in our culture, we’ve been slow to understand the devastating impact of alcohol, said Massey.

Alberta has been ahead of the curve in terms of benefits and research for FASD. But when you are in frontline work, said Massey, nothing seems to be getting better.

“We aren’t reaching the target population, which is a young woman who drinks, any woman who is of fertile age,” she said. “And they just don’t get it.

Massey advocates for a harm reduction model. Education needs to start in elementary school and carry on to university and college orientation. As soon as people are old enough to have sex, they need to understand the consequences of unprotected sex and drinking, even if pregnancy is not the intention. Raising awareness is the only way to prevent FASD.

Not only an Indigenous issue

Perhaps the most common misconception associated with FASD is that it is a disability only diagnosed in the indigenous population.

For Roberts, it doesn’t affect just one community.

“This is not an aboriginal problem,” she said.

One of the reasons people often make that inaccurate connection is indigenous children tend to get diagnosed more often with FASD, whereas others are more likely to get diagnosed with a more socially accepted diagnosis.

Dr. Gail Andrew is the medical director of the Glenrose Rehabilitation Hospital and FASD Clinical Services. She said there is less stigma in ADHD if you are a white, middle class family.

She said the stigma on the indigenous population is further perpetuated by the media, who often writes stories of individuals with FASD who struggle, “will commit crimes and go to jail.”

“There are no reports of success stories.”

Massey said we are asking all the right questions now, but not to everyone.

“There is a sample bias in what we do.”

There’s no denying there is a high population of indigenous people diagnosed with FASD, something Massey recognizes. It’s a marginally disenfranchised population, historically treated very badly by every system out there. She argues when your voices are not heard, you can develop maladapted coping strategies, which is often alcohol. But, booze doesn’t discriminate and it’s troubling when people assume this is merely a First Nations problem.

“It doesn’t matter who you are, what you do, where you come from, or where you live,” she said. “Booze is booze.”

Andrew defers to the social determinants of health when talking about the prevalence of FASD in indigenous communities, an area fundamental to understanding prevention and stigma, but that currently has little investment. Poverty, lack of educational opportunities, inequities in access to health and mental health care are “sadly more prevalent in First Nations” based on the Canadian history of their treatment, from early settlement to residential school maltreatment.

“These issues lead to higher rates of alcohol abuse and mental health disorders and not knowing how to parent as you were not parented yourself.”

Andrew said she did a focus group a few years ago and some of the First Nations women told stories of mistreatment when they tried to get health care, so they never went back.

In her clinic, poor prenatal care is common, as is poor nutrition, past violent relationships and continued stress, which can all compound the effect of prenatal alcohol exposure.

“All those preventable factors are more common in First Nations.”

What’s next

As part of an investment in FASD preventions and treatments, the Edmonton and area Fetal Alcohol Network Society partnered with the Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder Cross Ministry Committee – a government organization made up of nine separate provincial ministries – to implement the Edmonton and Area Fetal Alcohol Network Society Strategic Ten Year Plan. The plan focused on helping the government and different organizations increase awareness around the disability, through different education campaigns and provided support for individuals and their families. According to research detailed in Irene Shankar’s 2011 graduate thesis on FASD in Alberta, since 2007, the provincial government has invested nearly $37 million in FASD programs and services through organizations like the Edmonton and area Fetal Alcohol Network Society. Rogozinsky said their organization receives $3.2 million a year to distribute, but since their ten-year plan is approaching the end of its term, they need a new policy.

The organization will be breaking down their FASD programs and services based on a new, three-pronged approach. Their first focus will be on short term intervention, which will provide immediate support for individuals in an emergency. The workers who work in the emergency services area will have a very high case load of 30 to 60 people, but this ensures individuals will have immediate, short term help whenever they are in need. There is no limit on the amount of times youth and adults can access this service. The workers will then triage the individuals to see where they will be best supported based on their continued needs. Individuals whose needs and challenges require long-term mentorship (a one-on-one relationship) will be referred to services where they will be able to access those programs. Lastly, individuals, based on their needs, may be triaged to programs that focus on group work and support. While there are many group-based support organizations within the Children Services Ministry, a group model isn’t a traditional adult-based approach. The main goal for Rogozinsky is being able to provide immediate and strategic support for vulnerable adults, no matter their diagnosis. She said this new triaged approach should help reduce the waitlist for people with FASD seeking support services.

It’s Saturday and my phone won’t stop ringing with text messages from Ben.

10:28: “Ok where r u.”

10:38: “Where did u park.”

6:45: “The doors open at 6 pm.”

One of his support workers arranged for Ben to work security at a Roller Derby event in Edmonton and I’m going to watch him in action. The worker told me Ben had also texted her in the morning – hours before he’s normally up – asking if she was there to pick him up yet.

He’s there early to set up the arena and track area, fully committing to his role.

As I arrive, his back is to me, bent over as he arranges some chairs, but he’s hard to miss in his bright orange and yellow vest.

He doesn’t notice me right away; I watch him as he moves from task to task. He’s fast, vibrating, hardly able to stay still. His hands are balled up into fists.

Clench and unclench. Clench and unclench.

He finally spots me waiting by the glass and a big smile erupts on his face.

He walks over, his neck craning at every noise and movement.

“How do I look?” he asks me as he shifts from foot to foot.

You look ready, I say to him, before he turns as he’s called to duty.

Ready.