Fractured Forests:

Alberta's Seismic DilemmaDupperon is a 51-year-old fur trapper and although the trapping season just ended, he’s bringing supplies to his cabin for a 10-day bison hunt. The sleds are stacked high with drums of gasoline, bottles of water and butane. The three of us, Dupperon, his friend Rob Brown, and me, occasionally stop to refasten straps or dig out gasoline drums that flew out of the sled around a speedy corner.

As the soft mid-February light fades to yellow, pink and red, the wind blows swirls of dancing snow across the path.

The trail is mostly straight, an endless line through thick and entangled forest. We’re on a seismic line, speeding along at 40 km an hour. If it wasn’t for seismic lines, it could take days to reach his cabin, instead of a few hours.

***

But seismic lines have another purpose. To find petroleum, oil companies build seismic lines. Trees and vegetation are cleared so vehicles can drive down the lines and put explosives in the ground. The explosives are detonated and the frequencies are measured and used to determine if oil or gas is below. The size and length of the lines vary: some are 10 metres wide, others are two metres. Most stretch for kilometres, going far beyond the horizon, even when viewed from an airplane.

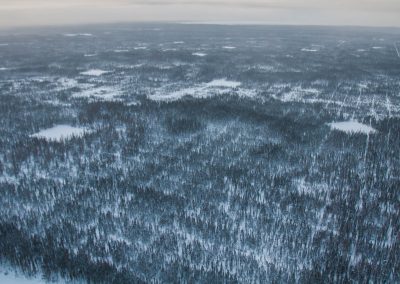

Seismic lines in northern Alberta | Photo by Liam Harrap

A line in the woods

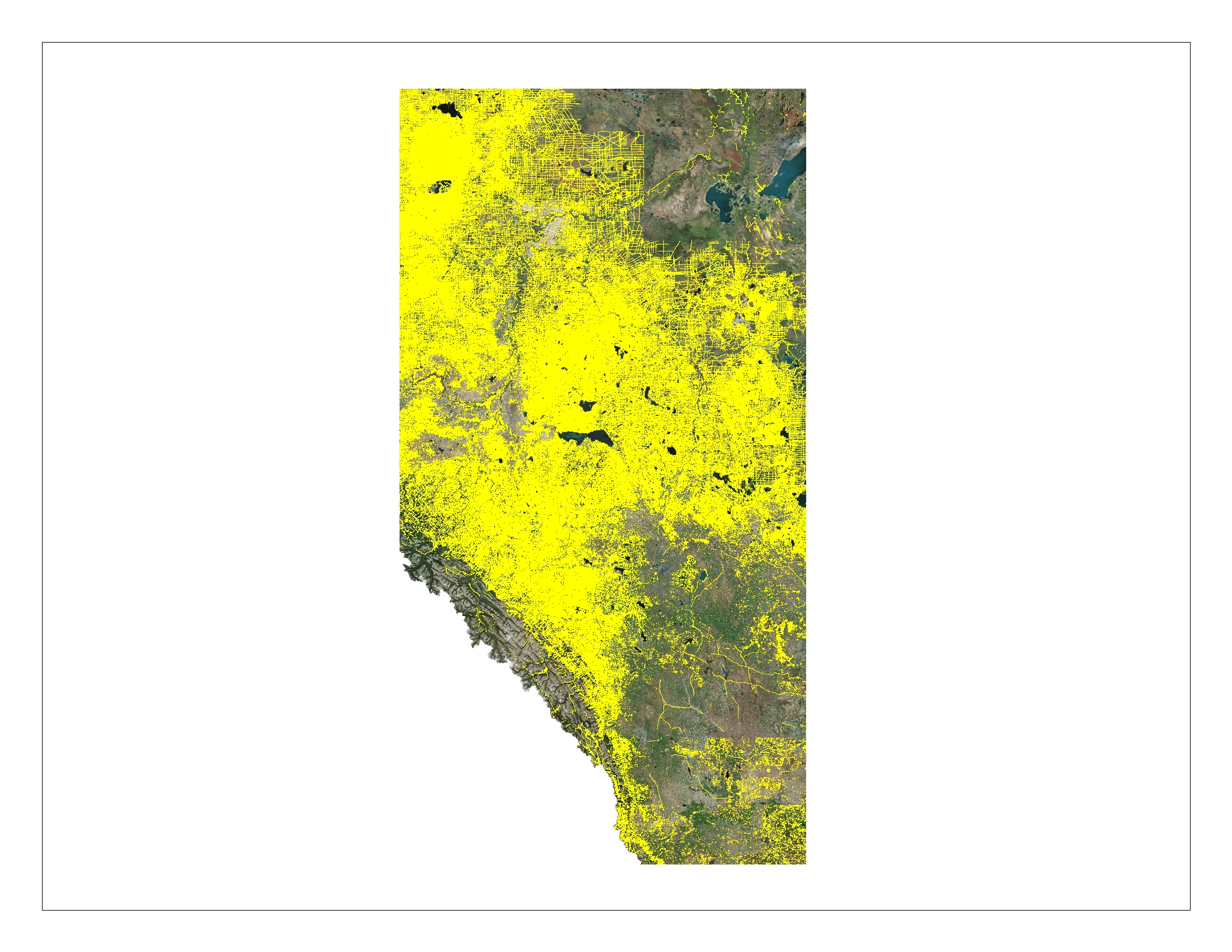

Seismic lines are the most common human-built disturbance in northern Alberta. Estimates vary, but there could be up to 1.8 million km of seismic lines in the province. When the lines were built, they were never meant to be permanent. So far, they have been left to restore naturally back to native forest, but many remain barren, even 50 years on. Studies indicate seismic lines disrupt wildlife, such as wolves and caribou. Wolves travel the lines and catch caribou, an endangered species. Caribou population decline has brought seismic line reclamation into the spotlight. However, the lines also disrupt birds, butterflies, bears, permafrost, and carbon storage. The effects of seismic lines also spill over into the adjacent forest by changing plant and tree composition.

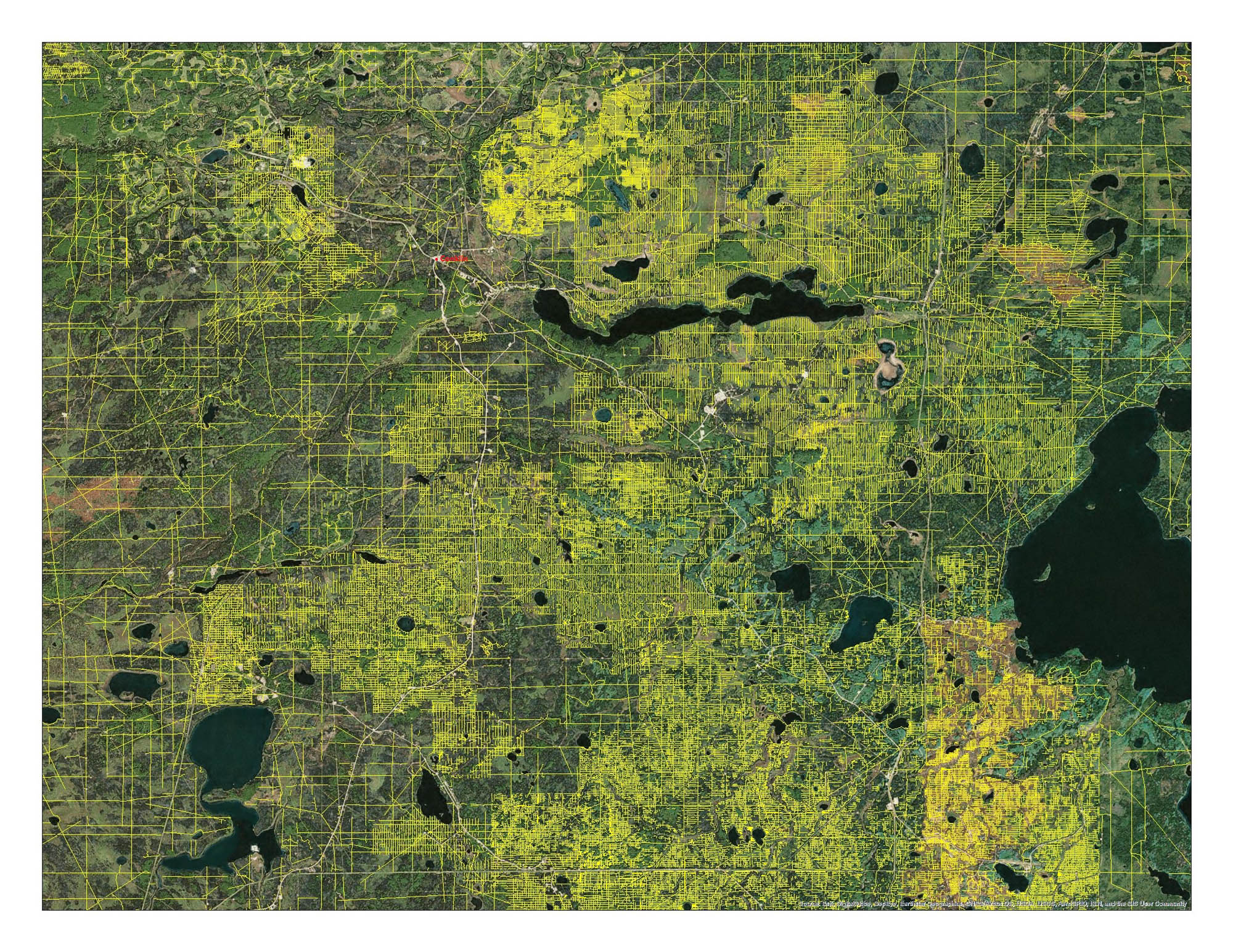

The construction of seismic lines has changed vastly. In the beginning, they were long, straight and wide. Over the years, the lines narrowed and began to ripple across the landscape. They were built closer together and became more frequent, as they are constructed in grids. Since the new lines are narrower, shorter, and not cut as deep into the soil, they are called “low impact.” However, due to their higher abundance and frequency, they may have a noticeable negative and under-researched effect on wildlife, plants, and people.

Indigenous peoples of northern Alberta say the woods are becoming empty and seismic lines are largely to blame. There are fewer animals to hunt and trap. Traditional medicine and plants are being lost. Not only are seismic lines a vector of change, but they threaten the environmental integrity of northern Alberta: a creeping spider web of disturbance that’s continuing to grow into areas previously untouched by seismic activity.

While drilling and mining for oil extraction requires reclamation by law, no such legislation exists for seismic lines. Although most scientists advocate for seismic lines to be reclaimed, the issue is controversial due to the expense, loss of access to the land, potential job loses and difficulties in replanting. And even if seismic lines are reclaimed caribou may still be doomed.

***

We get to Dupperon’s cabin in darkness. Last December, he arrived and found the interior in tatters. A fellow snowmobiler hadn’t properly closed the door or set the electric fence. A black bear got inside, smashed it up, and ate all the food.

“There’s all kind of beings that live in places like this,” muses Dupperon as he passes a hot toddy of rum, coffee, syrup, and creamer. He switches on the satellite radio and we listen to “If drinking don’t kill me her memory will” by George Jones.

***

The largest biome in the world: the boreal forest

The sun peeks over a stand of spruce trees and dances on the shores of a frozen lake near Dupperon’s cabin. A herd of bison break the silence as they’re chased by a pack of wolves, knocking down scrawny spruce trees as they flee. A white wolf watches as the herd disappears, trees and bushes madly swaying as the herd tramples past. She glances at the wildlife video camera and appears to be smiling.

Welcome to the boreal forest — the largest intact forest in the world.

And home to 2.5 million Canadians.

It’s also the largest biome part from the oceans and makes up 29 per cent of the world’s forest cover. A biome is a community of plants and animals that have common characteristics for their environment. This green halo of boreal forest stretches through Canada, Scandinavia, Japan, Mongolia, Scotland, the U.S, and Russia. In Canada, it covers almost 60

Duperron’s trapline is a region defined by water. Roughly 85

However, the landscape varies. Canyons, mountains, swamps, sand deserts, vast rivers and gloomy lakes can be found next to each other. It’s the largest terrestrial carbon sink storing 11

“In the course of a few

Woodland boreal caribou were designated as threatened in 2002 by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. It’s unknown how many woodland caribou are left in Canada.

For Duperron, the boreal is the real world. The trees, the plants, the animals, and not the “stuff covered in concrete and metal.” Although he usually traps alone, he never feels alone. He’s surrounded by animals, which he calls his friends.

“I don’t find this as the middle of nowhere. This is home. And there are wonderful friends out here. They might not speak English or French or Spanish, but we talk.”

Alberta has less remaining intact boreal than any other province or territory at 16 per cent. To be dubbed “intact”, a Global Watch Canada study determined that each forest block must be at least 50,000 hectares, larger than the country of Andorra, so outer boundaries can buffer against human influences. The other provinces have at least 50 per cent of their original boreal cover. Only 10 per cent of the boreal is currently protected nationwide.

And here’s the problem: most of Canada’s oil reserves are in the boreal.

Scott Nielsen, a conservation biologist at the University of Alberta, calls seismic lines in the boreal “corridors of movement.” Not only are they used by wildlife, but they are frequented by hunters, fur trappers, researchers, forest fire fighters, industrial workers, foresters, and recreationalists as they provide easier access to the land.

While Dupperon has been a fur trapper for more than 45 years, he says his family has been trapping for more than 400 years. Trapping is in his blood.

“Border collies are bred to herd things. We were bred to trap things.” Dupperon says he cannot imagine a life without it.

Alberta: oil country

Alberta is the largest exporter of oil in Canada. In 2015, it produced almost 80 per cent of Canada’s oil. Most of it comes from large oil sand deposits. These deposits give Canada the world’s third-largest oil reserves after Saudi Arabia and Venezuela.

The oil sands are made up of three separate areas: Athabasca, Cold Lake, and Peace River. The Athabasca oil sands are the only ones suitable for surface mining, while the other two must be produced by drilling, such as in-situ drilling (translated from Latin means “in position”). The first commercial mine of the Athabasca oil sands was opened in 1967 and was the first operational oil sands project in the world.

Much of the oil produced in the province is found using seismic lines. Today, seismic lines are particularly useful for in-situ oil. In 2017, most oil produced in Alberta was in-situ.

Seismic lines: a history

Seismology is the study of how seismic waves move through the Earth and interact with different geological layers. It was first used in the mid-19th century to study earthquakes. In Canada, the first seismic survey for oil was conducted in Turner Valley, Alberta, in 1929. In the early days, seismic lines were wide, straight, and spaced at distances of 300 to 500 metres. Bulldozers were used to clear the land and remove top soil. Little consideration was given to restoration or replanting. These seismic lines were called 2D or legacy lines.

Sometimes it’s hard for 2D seismic line to return to natural forest as bulldozers removed the layer of organic soil | Photo courtesy of Scott Nielsen

Sometimes instead of explosives, large trucks with vibrating plates drive down seismic lines. The plate shakes the ground, and the frequency is measures to determine if oil is below | Photo courtesy of Mike Doyle

Depending on the roughness of terrain, trucks with vibrating plates can be preferable over explosives for determining if oil is below | Photo courtesy of Mike Doyle

Today, seismic lines are most commonly built in the winter when the ground is frozen. Northern Alberta is wet and in the summer it can be muddy and diffuclt to move equipment. It is thought since the ground is frozen in the winter there is less damage to the environment | Photo courtesy of Mike Doyle

It was recognized that cutting seismic lines was significantly impacting timber resources. Therefore, the Alberta government instituted a compensation fee for timber damages. To get lines narrower, the province offered a financial incentive: a 50-per-cent rebate in the timber damage fee, which prompted reductions in width from seven to eight metres to as low as two metres. They also began to wiggle and bend, to reduce the line of sight for animals travelling the lines. Seismic lines became similar to small waves, faintly rippling across the landscape.

Today, seismic lines can be as narrow as 1.75 metres and are built in a grid pattern, sometimes only 50 metres apart. The timber damage fee is waived when lines are less than two metres wide and less than 200 metres long. However, if they are wider or longer they are subject to fees based on the region and type of wood cut. For example, it could cost $1,140 per hectare near Slave Lake, Alberta or $362 per hectare near Edson, Alberta. There is also a Forest Protection Levy which is applied at $15.55 per kilometre across the province for seismic lines.

In peatlands its easier to distinguish 3D seismic lines as regrowth is slower | Photo by Liam Harrap

Zama City, in northwestern Alberta, has the highest concentration of seismic lines in the province.

Mulchers are like bulldozers, but they have a rotating drum on the front that spins at very high speeds, literally “mulching” everything in its path, similar to a 1950s lawnmower The idea behind mulchers is to remove vegetation but leave the soil intact, uncompressed. The mulched vegetation helps regrowth.

***

Wind bites our faces as we ski-doo down seismic lines. Today, we’re going to Wentzel Lake to check wildlife cameras for bison. I stick close to Dupperon as the maze of lines are confusing. Left, right, straight, double back. Although ski-doo tracks go everywhere, Dupperon never wavers. He knows which line is correct.

***

3D seismic lines meander and weave. In some habitats, esp in dry forest, they can be difficult to find after use | Photo courtesy of Liam Harrap

Drilling and laying explosives along a 3D seismic line. Seismic work usually takes place in winter | Photo courtesy of Mike Doyle

Mulchers grind up trees, shrubs and plants. Mulched wood can make regrowth faster | Photo courtesy of Mike Doyle

Little to no research has been done on the effects of explosives along seismic lines. However, Tigner says, it’s assumed they have little affect.

The 3D lines provide more complex and higher quality data, says Tigner, as the lines are closer together. They offer a far better underground map than 2D ever could.

In-situ is complicated and having good data, says Tigner, makes the process easier and more cost effective.

Amit Saxena, a biologist at Devon Energy, says seismic exploration is “a big game of battleships.”

“Decisions of where to put seismic grids is based on how much we know and how much we need to figure out,” says Saxena.

A seismic company does not solely cut seismic lines, but mainly collects geophysical data. Tigner says the only reason seismic lines exist is to move equipment. Ideally, the lines wouldn’t exist.

“It’s a huge cost. What we really want to know is what’s going on under the ground. The only reason they have a line is to get equipment down.”

Tigner says in rough, rugged, and remote terrain it can cost up to $100,000 per km to cut seismic lines. If seismic lines are near an urban centre, with flat easy-to-access terrain, it could cost $3,000 per km.

While replanting and restoring seismic lines to natural forest is still in experimental stages, Michael Cody, a biologist at the energy company Cenovus, says the average cost of restoration is $10,000 per kilometre.

Around the globe

Although Alberta has some of the highest concentrations of seismic lines, they are found worldwide.

“Anywhere there’s oil and gas in forested areas there’s seismic lines,” says Tigner with a chuckle.

There is an unbroken wave across North America, says Tigner, of unstoppable development from the Gulf Coast all the way to the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains, through New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, Alberta, British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba.

However, at the 60th parallel there’s an “abrupt” stop. Across most of the Northwest Territories, there are no roads, pipelines, powerlines, or seismic activity. It’s an unblemished landscape.

“Due to disagreements of land claims and remoteness, we haven’t got there yet,” says Tigner.

The only area of Alberta with little-to-no seismic lines activity is in its northeastern corner, by Fort Chipewyan on Lake Athabasca.

Russia is also a huge oil producer and like Canada, largely covered by boreal forest. However, Tigner says Russia is closed when it comes to the “nitty gritty” and it’s largely unknown how it produces oil.

However, Tigner says the reason 2D seismic lines in Western Canada are distinct compared to other regions is due to bulldozers digging deep into the soil substrate and stripping away the surface layer of vegetation.

“You’re literally cutting into permafrost and kicking back the ecology of those lines, like a thousand years,” says Tigner.

By comparison, in South America, the locals will go into the jungle and cut very narrow trails, which leaves the soil more intact. The footprint of the line will recover faster because there’s less to recover and the jungle has higher growth rates. In Papua New Guinea, seismic lines are different. Elaborate scaffolding structures are built through the jungle because the bush is incredibility difficult to get through and the landscape is so rugged.

“They’re called sky bridges. They have ladders that go down to the ground so you can put your recording equipment and drill your dynamite,” says Tigner.

Trees of the boreal are too scrawny, scrubby and stunted for bridges.

While Tigner says it would be ideal to stop using seismic lines, at the moment there are few alternatives. One is air surveys, which involves flying planes in a grid to look for electrometric anomalies, but they aren’t reliable.

“Seismic produces much much more conclusive pictures and interpretations on what’s going on in the ground.”

It appears we’re stuck with seismic lines – at least for now.

However, Tigner hopes this will change in time.

Tigner says energy companies must be creative when thinking about the future of seismic lines. Chad Willms, project manager for caribou range planning at Alberta Environment and Parks, says it would be “great news from an ecological perspective” if seismic lines were no longer needed. However, the technological advances need to come from industry.

Canada’s Oil Sands Innovation Alliance (COSIA), a collaboration of 13 different energy companies, such as Suncor, Syncrude, Devon and Cenovus, has initiated a challenge. It’s asking for new proposals that would reduce the environmental impact of energy industries.

According to their website the goal of the challenge is to “investigate alternative exploration techniques that would help lead us towards zero land disturbance for in-situ projects.”

It’s little understood why some seismic lines naturally revert to native forest and others do not. Seismic lines may remain barren for several reasons, such as sandy soil, loss of organic soil, flooding, shading from adjacent forest, and recreational use by all-terrain vehicles or ski-doos. Dupperon says the lines on his trapline become overgrown quickly. Too quickly, in his opinion. Part of the reason his lines become overgrown could be due to melting permafrost, which provides moisture for plants.

***

The sky is cloudless. We stand on top of a bluff overlooking Dupperon’s trapline. The Caribou Mountains gently rise in the distance behind a sea of spruce and frozen lakes. Brown surveys the land with binoculars, looking for wildlife.

“Wow,” he mutters. “This view is incredible.”

Faint lines ripple across the expanse, but they’re hard to see. Dupperon says he use to travel those seismic lines a few years back, but now it’s too difficult. The forest has taken them back. We jump back onto our ski-doos and speed off. Branches grab our jackets as we whiz past, as if they’re slowly reclaiming this line as well.

***

The 4D seismic lines are mostly the same as 3D, with one exception. They include a 4th dimension — time. They follow the shift and change in bitumen deposits over time, as bitumen is extracted.

Nielsen says these new lines are of particular concern. Since the entire bitumen deposit is under pressure, as it’s removed, the deposit will begin to shift and move. It may get deeper and/or spread out.

New data and maps are needed to determine what the shift in bitumen looks like, so new seismic lines may be built to reassess the bitumen deposit. Old seismic lines may also be used, but they would probably be re-cleared of vegetation.

“It’s concerning, as they would go back to re-disturb seismic lines and keep them open. And we don’t want them open from an ecological perspective,” says Nielsen.

Amit Saxena, Devon Energy biologist, says his company has started to build 4D lines on some of its energy leases.

Life on the line

Kevin Didyk, 41, has cut seismic lines for 23 years. He says there aren’t as many seismic cutting companies as there use to be.

“It’s a dying business. I probably only know of three companies that are left in Alberta. A lot of oil companies are just re-using old data for research and drilling.”

Didyk works in crews of three: a faller, bucker, and cleaner. Didyk is a faller and earns $40 an hour. On a good day, Didyk says, one kilometre of seismic line can be cut per hour. Speed depends on the roughness of terrain.

Days are long, cold and hard.

Although the job is hard, Didyk says he wouldn’t do anything else.

He’s encountered grizzlies, discovered forgotten fur trapper cabins and eaten lunches beside hidden waterfalls. He says he’s left footprints in places no-one has stepped before. Every day is an adventure.

“I’ll be working and turn around. There’s a moose right behind me. Looking at me. Staring. Now that’s a story.”

And dangerous.

“There once was this wind storm,” he says. “A co-worker went looking for his buddy and found him pinned under a fallen tree. That was the end of his buddy.” Didyk goes quiet.

Another time, a seismic worker was driving an all-terrain vehicle down the line, sped over a hill and hit a tree. He broke his neck and died on the spot.

While the seismic business isn’t booming, Didyk says he hopes it will pick up as oil prices increase.

“It’s something I want to do until I retire. That is, if it lasts.”

Alberta’s draft caribou range plans

Boreal woodland caribou populations have been declining for decades. In 2012, the federal government asked the provinces and territories for strategies to protect caribou. Last December, Alberta released its draft caribou range plan.

The draft is the first of many that should lead to government action and policy, as it provides a framework for what could be expected. It is the first major provincial document that lays a foundation for considerable reclamation of seismic lines. Seismic lines are in the spotlight because they are thought to be one of the leading causes of caribou decline in the province as they help wolves travel and track caribou.

In 2002, boreal woodland caribou were classified as a species at risk. There are 15 different woodland caribou herds in Alberta. According to Canadian government data, none of the herds are increasing in numbers and most are declining. Studies indicate that if no action is taken, caribou in the province could be extinct in 50 years.

The draft proposes to create 1.6 million hectares of new provincial parks. This is meant to help achieve 65 per cent of undisturbed habitat in each of the 15 caribou ranges. According to the federal government, 65 per cent gives caribou a 60 per cent chance of being self-sustaining.

The draft also includes $85 million for replanting seismic lines, which would roughly restore 8,500 km of lines. There are up to 1.8 million km of seismic lines in Alberta, 250,000 km of which are in caribou ranges.

Wolf culling has been used by Alberta to help caribou populations for decades, the draft proposes to continue the practice.

A protest against the draft caribou range plan outside Alberta's legislature | Photo by Liam Harrap

The public fights back

Dupperon sits at a table with other trappers at a Royal Canadian Legion in Edmonton. The trappers are debating with Alberta Environment and Parks staff about the draft caribou range plan. They drove seven hours, one way, to be here. This information session is the second of six that are being held across northern Alberta.

“I hate cities, but it’s important for us to be here,” says Dupperon. His twinkling hawk eyes scour the Alberta Environment and Parks staff, who shift uncomfortably. Just prior to this information session, Albertans working in industry and forestry held a protest outside the Alberta legislature. They wanted Premier Rachel Notley to scrap the draft and “save jobs”.

Reaction to the proposal has been large, swift and mostly negative. While caribou conservation is complicated, some participants claim this draft may be unrealistic, doesn’t go far enough, causes economic harm and doesn’t even help caribou.

Most of the people attending the information session worry about potential economic impacts.

“We will effectively destroy our rural economies. And we won’t have caribou either,” says Roy Hilts, a town councilor from Whitecourt. Hilts estimates more than 1,000 jobs could be lost in his area. Hilts mostly disagrees with the draft.

“I really do think it may cause one of the mills in Whitecourt to close. It will literally put people out of work.”

“It’s possible, but there are a lot of conditions at play. Trade agreements with the U.S., oil prices, all of those are causing job losses and creation.”

Hilts says the new parks and need for 65 per cent of undisturbed habitat in each 15 ranges, will harm business, by reducing land available for logging and oil and gas. According to the 2016 census, 264,000 workers or almost 12 per cent of Alberta’s labour force is employed in oil and gas.

While Dave Hervieux, a caribou biologist with Alberta Environment and Parks, acknowledges that climate change could be impacting caribou, he says there’s little literature to support it.

“Very little is due to climate change. Most is due to human disturbance,” such as seismic lines.

Dupperon says he’s worried that he will be prohibited from trapping in the Caribou Mountains.

“I use seismic lines every single day. In a lot of areas we still don’t have reasonable enough access to manage those areas properly. And we’re keeping an eye on wildlife populations, not just caribou. We’re the indicator species on the land.”

“We will keep the right seismic lines open for trappers,” says Willms.

However, Dupperon is skeptical. He says it’s possible that the majority of seismic lines in the Caribou Mountains could be replanted and closed, making it difficult for Dupperon to access his trap line. Dupperon says 90 per cent of his traps are located on seismic lines. He mostly traps pine marten and lynx.

It’s a trade people choose because of the lifestyle and not the money. There are more than 1,500 registered trappers in Alberta.

***

As we ski-doo near his cabin, we notice many hoof prints crossing the line. They criss-cross our path sticking to peatlands and using the line little for travel. There are countless tracks.

“I see caribou tracks far more than I used to,” nods Dupperon.

“The caribou in this area are fine. Who knows, maybe there’s too many.” He accelerates his machine. Brown and I follow. An owl swoops across the line. Dupperon points to it and grins.

***

“If this draft came into play tomorrow, it would render seismic dead on arrival.” Tigner says it’s difficult with in-situ oil production to get reliable data from such large spacing. In-situ is a complex process, where precision is key. Currently, seismic lines in the boreal can be as little as 50 metres apart.

Tigner says the government has a difficult line to balance; however he’s surprised how little the plan seems to understand the system from a full perspective. While the draft incorporates biological elements, it fails from a geophysical perspective.

“It’s sort of like we’ll compromise by allowing some activity, and it’s like well what’s the point of compromising if your compromise is going to render seismic ineffective in parts of Alberta that continues to be the powerhouse of the province and arguably the country.”

Tigner says that if the government truly wants to protect caribou, something must be sacrificed. It should “flat-out” say no to seismic lines, instead of trying to please everyone.

“It’s surprising to me that not harder decisions were made. The can was kicked down the road yet again.” If seismic lines are bad for caribou, then the government should stop allowing them.

Not everyone attending the information session thinks the draft is bad news. Don Kenyon, a retired teacher from Devon, Alberta, welcomes the draft and hopes it will soon become legislation.

“The plans are here now. It needs to be law, otherwise it just leaves too much wiggle room.” Kenyon hopes that the government will not back down and “give into industry.” It has an obligation to protect caribou.

Regardless, some say caribou are doomed, no matter what the government does. And instead of putting money and resources into trying to save them, perhaps we should ship them elsewhere.

“We’re literally going to spend billions of dollars to restore habitat and we don’t even know if it will work. We as industry, would say, we’re better to round them up and move them into the territories, where they’re still doing well. And give them a chance to survive. Maybe it’s time they move in with their cousins to the north,” says Mike Doyle, president of the Canadian Association of Geophysical Contractors (CAGC) in Calgary, a trade association that represents the business of seismic in the Canadian oil and gas industry.

Even the Alberta government acknowledges that the draft may not save caribou.

“Forestry started to complain “oh no, you’ll kill us. Blah blah blah” and in the end the government backed off. That’s negative for caribou. I don’t see anything different in terms of this government sticking to their guns against the energy sector. Forestry is important, but it doesn’t hold a candle to the economic power that the energy sector holds.”

Boutin says it’s caribou decline that’s driving the conversation for seismic line restoration. Without the animal’s decline, it’s unlikely reclamation would be discussed, he says.

And Boutin was right. Last month, the Alberta government suspended the draft, citing “economic concerns.” The province is asking the federal government for financial aid. Other provinces have also started to raise concerns about the cost of saving caribou.

Last month, the Quebec government said it’s too expensive to save a small herd whose habitat has been decimated by human activity. The province estimates it would cost $76 million to help the 18 remaining animals in the Val-d’Or herd, with a slim chance of success.

In the federal government’s recent budget, $1.3 billion has been earmarked to expand protected areas and help endangered/threatened species. Ottawa is set to publish a report in April on steps being taken by provinces to protect critical caribou habitat.

If it’s determined that boreal caribou are not being protected, the federal government could impose a cabinet order that would allow the species at risk act to be applied on provincial lands. It would prohibit any development, such as oil drilling and forestry, that could harm the animals.

However, the draft isn’t dead. Chad Willms, project manager for caribou range planning at Alberta Environment and Parks says an updated version with more details about the caribou ranges should be released in the next few months. Two weeks ago, an Albertan delegation went to Ottawa to speak with the federal government on the potential economic impacts of caribou habitat protection.

Ski-dooing along Dupperon's trap line | Photo by Liam Harrap

A commotion in the woods

A crow flies over a bog in northern Alberta. Black feathers whisper across the cloudy sky. Spruce and tamarack trees shiver in the wind. Large snowflakes begin to fall and a nearby squirrel chatters.

In the middle of this boreal forest there’s a distinct line. It’s perfectly straight, cleared of vegetation, going far beyond the horizon. If you go further into the woods, you come across another line. And another. And another. There are thousands.

On this particular line, there’s commotion slinking through the frozen air.

Beep…Beep…Beep

A worker in a reflective vest and hardhat drives a backhoe. Stirring, shifting the dark and nutrient soil. A helicopter buzzes above. Tree stems on the edge are bent across the line, making travel along it difficult.

This is part of Cenovus’s restoration pilot project near Cold Lake, Alberta. The energy company is spending $32 million to treat an area the size of Edmonton.

Treatments include planting trees, creating wood piles and leaning tree stems to block the lines. It’s thought wolves travel the lines and catch caribou.

So far, Cenovus has replanted more than 700 km of lines in caribou ranges. They plan to restore 3,900 km in total. They hope the work will help caribou survive.

Although energy companies aren’t required by law to restore seismic lines after use, Michael Cody, a biologist at Cenovus, says “environmental integrity is important to our company.”

While surface oil sand mines commonly steal media attention, they only cover only 0.1 per cent of Alberta’s landmass. But seismic lines on the other hand slice across the province, cutting through provincial parks and wilderness areas.

So far, only national parks have been spared the onslaught.

However, replanting seismic lines is tricky and not well understood.

“Honestly, I think it’s an open question. There’s been a lot of restoration for sure. But to be honest, just establishing trees in the ground isn’t restoration.,” says Scott Nielsen, professor of conservation biology at the University of Alberta. Nielsen’s lab specializes on research pertaining to seismic lines.

It all depends on how you define success.

“That’s the billion-dollar question,” says Nielsen, “what is success and what would it look like?”

Nielsen says that while a three-metre-high tree may stop wolves from traveling down seismic lines, different species may not view the forest as “recovered”.

“An ovenbird would perceive two or three-metre height on a seismic line as still being a massive open corridor in some habitat. A fisher might perceive it as completely different and a rare plant as completely different. Every species has its own niche and its own response,” says Nielsen. An ovenbird is a small songbird from the warbler family.

It isn’t just wolves and caribou that are affected by seismic lines. A study by the University of Alberta in 2005 suggested ovenbirds use seismic lines as territory boundaries. Since there is less leaf litter on the lines, there are also fewer anthropoids. An ongoing study by Nielsen has found that butterflies are found in higher abundance and diversity levels on legacy lines. However, diversity and abundance of butterflies decrease as the line width decreases. Bears use seismic lines for travel, while smaller mammals, such as marten avoid lines wider than two metres. Research is currently underway on how seismic lines affect beetles and spiders.

A report by the Canadian government indicates that once a forest is 40 years old, it can be counted as caribou habitat.

Regardless, getting trees to grow is problematic. Nielsen says there are two types of ecosystems in the boreal where restoration is proving difficult. Dry, sandy, pine forests. And peatlands.

Peatlands are low lying areas that have an accumulation of decaying vegetation. They are notoriously wet and when seismic lines are built, the vegetation becomes flattened and is pushed below the water table, making it difficult to plant trees.

As fate would have it, peatlands are heavily favoured by caribou.

A seismic line through peatlands | Photo courtesy of Scott Nielsen

Peatlands are home to many mosses. Vast patches of vibrant reds, oranges, and yellow sphagnum mosses grow on hummocks, just above the water table. However, when a seismic line is built, the ground is leveled to the water table. It’s too wet for trees to establish and for many mosses. The line, instead grows grasses and sedges. Perfect forage for deer and moose.

“Historically, peatlands were terrible for food for deer and moose. However, when you bring in seismic lines, it brings grasses, sedges, and berries. All of which are preferred browse,” says Nielsen.

In the past, oil companies would put grass seed on seismic lines. Even if the grass didn’t match the native environment, any kind of vegetation was thought to be better than no vegetation. But grass is an aggressive plant and grows rapidly, shades, and smoothers competitors, such as small coniferous seedlings, making it harder for trees to establish. Grass can keep the lines treeless.

Deer and moose are preferred prey for wolves. Where they go, wolves follow. And if it’s peatlands, the chances of running into caribou increases.

“Caribou don’t go into upland sites because predation is too high. These peatlands in the past have provided these refuges that are safe from wolves. Wolves didn’t go in there because there weren’t other ungulates. It’s now all flipped.”

Studies have shown that it’s difficult for caribou to exist when there are more than six wolves per 1000 km ². In northeastern Alberta, wolves number 12 to 13 per 1000 km ². In the Little Smoky caribou range, there are 30 wolves per 1000 km ².

“It’s the highest wolf density in North America,” says Amit Saxena, a biologist from Devon Energy, referring to the Little Smoky.

***

A chainsaw cuts through the morning air. Dead spruce trees fall and we drag them onto the seismic line to be cut into logs. As Dupperon works, the snowpack is up to his knees. The woods are an entanglement of chaos. Travel is slow.

“You know, caribou would be upset if seismic lines were reclaimed. They use them a lot. They have a better chance for getting away from a wolf on a seismic line, then off it,” says Dupperon.

“I don’t see any negatives from seismic lines. At least, in my area.” Dupperon says in 16 years, he’s only seen one caribou killed by wolves on his trapline.

He spots another old, weathered tree and pushes it over with a crack. It falls and sends up a small plume of powder.

***

Another type of reclamation and “it’s free”

Millions and millions of dollars are going into research on how to restore seismic lines to native forest. One possibility is fire.

Wildfire is key in maintaining the health of a forest. Many tree species need fire to open their cones. Nielsen’s lab has conducted research on whether seismic lines would restore back to forest after a fire.

“This type of restoration is called passive. And the best part is it’s free,” says Nielsen.

“Peatlands also burn less often,” says Nielsen. And for helping caribou, peatlands are the priority.

“That’s where you need to spend your restoration dollars.”

According to Alberta government data, there are more than 200,000 km of seismic lines throughout peatlands in the province.

“We don’t even know what the relationship is between the total amount of these linear features (roads, pipelines, powerlines, seismic lines) and caribou. It’s certainly not linear,” says Boutin. It’s possible that caribou react so badly to seismic lines that once they were originally built, their numbers plummeted. It isn’t a matter of mileage, whether it’s 10,000 or 900,000 km. Just having them on the landscape could be negative and caribou populations unrecoverable.

“If that’s the case, to have any influence we would have to get rid of damn near all of it. And that’s a huge challenge,” says Boutin.

While reclamation on seismic lines is still in experimental stages, George Duffy, lead caribou range planner at Alberta Environment and Parks, says it’s better to start sooner than later.

“I steal from an old Chinese proverb all the time. The best time to plant a tree was 40 years ago, the next best time is now. We can always wait and learn more, but if we don’t start doing action on the ground, we’ll look back 20 years from now and say ‘Boy I wish we had planted some trees’”.

Duffy says the government will learn how to restore seismic lines as they go.

Chad Willms, project manager of the caribou range planning at Alberta Environment and Parks, says it would have been better if government and industry had started reclamation of seismic lines decades ago.

“The earlier we could have done this, the better. But it’s better late than never.”

Beyond the edge

It isn’t just the lines themselves that are concerning, but the effects along the edges. A report by the Canadian government indicates that environmental changes go beyond the lines and into adjacent forests. Since seismic lines provide a break in tree canopies, more light reaches the forest floor. Therefore, there can be increased growth rates of trees growing at the edge of seismic lines. With an increase in tree growth, the competitive balance between species may shift. Resulting in fewer shrubs, flowering plants, and mosses.

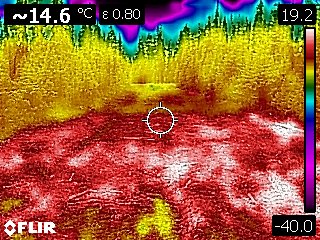

There is more wind on seismic lines, sometimes up to seven times more, compared to adjacent forest, which can increase tree mortality. More deadwood along the edge leads to more fungi and lichens. More wind also disperses seeds faster and further, which can be problematic for invasive species. Due to lack of shading, seismic lines are warmer.

“With edge effects, seismic lines can have an environmental impact that far exceeds any other human disturbance in northern Alberta,” says Nielsen.

Seismic lines are also associated with permafrost thaw. In areas of northern Alberta, a layer of soil is frozen year-round. This permanently frozen layer is sensitive to human disturbances, such as soil compaction and removal of vegetation.

It isn’t just seismic lines

Roads, pipelines, powerlines, and mines, are all thought to negatively harm caribou. Adding the total mileage of roads, pipelines, and powerlines together in the province adds up to one million kilometres. If seismic line mileage is included, it could be up to four million km of lines slicing, slashing, and segmenting Alberta. It’s equal to going to the moon and back more than five times. However, Nielsen says there is one important difference between roads, pipelines, powerlines, and seismic lines.

Seismic lines were never meant to be permanent.

“The highways were established. The pipelines. People decided that they were fine with those lasting forever. But seismic lines were never meant to last,” says Nielsen. In most cases, they were built and forgotten. Their purpose completed. It was expected that the lines would just naturally recover back to forest, however thousands upon thousands didn’t, leaving treeless scars across the province.

***

Yellow ice covers the creek and we slow to a crawl. Dupperon’s ski-doo starts to twirl, the belt beneath failing to catch snow. His machine does a slow waltz across the ice, straightening in the fresh powder.

“Before seismic, trappers used creeks. And lots died. You fall through the ice, you break through overflows. It’s extremely dangerous,” says Dupperon with a toothless shrug. He lost all his teeth when a bull stepped on his face.

“I’m on borrowed time. I should have died years ago.” Once, his machine fell through ice and he was up to his chest in water. When he eventually got the ski-doo free, he managed to get back to his cabin quickly using seismic lines. Without seismic lines for his speedy get away, he could have died.

***

“And the Crown said, ‘thanks for that. We checked it. You put seed on it. That’s good enough for us,’ ” says Amit Saxena, a biologist at Devon Energy, between bites of a jelly donut.

We chat in a cafeteria-like area near Devon Energy in Calgary. Our meeting spot is connected by skywalks to surrounding glass towers that house Murphy Oil, Alberta Energy Regulator, and Birchcliff Energy. Shell Canada is across the street. By comparison to a few years ago, says Saxena, the buildings are quiet. Many workers were laid off during the recent economic downturn.

Saxena takes a sip of coffee and says,” Everyone has washed their hands of old seismic lines.”

Sometimes it may be easier to pretend they don’t exist, which is difficult if they’re everywhere.

The impact of seismic lines on traditional lives

The Powders

In a house on a nameless gravel street Mary Powder, 77, prepares ribs. The walls are plastered with family photos, there’s a pink crucifix on a table, and a yellow balloon with a smiley face. An award for Best Trapper of Year 2003 adorns the wall. Fish swim in a tank and her husband, Zachary Powder, 89, watches the news.

“You’re not a woman,” says Mary Powder to me when I arrive.

“You sounded like a woman on the phone. I told my grandson when he went to get you on his quad to look for a woman.” I blush and nervously apologize for my extra Y chromosome.

Zachary Powder has been trapping in Fort Mckay for more than 50 years. The Powders are apart of the Fort Mckay First Nation. When oil companies began building seismic lines in the region, everything changed.

For the Powders, trapping was essential. Not only was it an important part of their culture, but it put food on the table. The Powders wouldn’t agree with Dupperon. For them seismic lines have destroyed everything.

“It’s how we brought up all our children. We get money from the fur. We trap. Nobody scared away the animals before. Now, all the trees are taken down. They won’t grow. Damage to everything,” says Mary Powder.

“It was a good life before the oil companies came. Better than now. Our life has gone away. Never comes back. Never the same as before.”

The landscape is fragmented, cracked, and empty.

When asked if seismic lines should be replanted, Mary Powder interrupts.

“Never mind if they replant! They’re not our god. God grows everything. How many years will it take before something comes up? Because they killed all the roots. How many years before something comes up again?” For the Powders, the damage is done. Nature is the best re-planter and restorer of the land. It should be left to do what it does best – grow. Even if it takes a lifetime.

As I leave in the fading twilight, I notice an old pickup truck in the driveway. There’s a sign attached to the back window.

To love a person is to see all of their magic.

And to remind them of it when they have forgotten.

Their small house is surrounded by a fence decorated with flowers and butterflies. A line of white rocks lay in front. All is quiet. Yet, the air is sweet and sickly from nearby mined bitumen. The smell cloaks the Powders’ home.

The man from the woods: Alden Cree

Alden Cree from Fort McMurray First Nation grew up in the bush. His family would canoe the rivers: Athabasca and the Peace. Sometimes they wouldn’t see another human for weeks. Time was spent hunting, trapping and fishing. They were always preparing for winter.

Now 56, he says he doesn’t go into the bush as much. In the past he’d hunt moose, but today he has to travel hundreds of kilometres to find one. He’s watched as the woods around Fort McMurray have disappeared.

He says it’s hard for people to understand the damage of seismic lines because they probably didn’t grow up in the bush.

“Now, people spend more time watching TV, more time on their phones. They don’t have the connection to the land that the other generations had. Living off the land, where the berries grow, where the animals migrate. This generation has lost touch.”

The woods that Cree grew up in are gone. Roads, power lines, pipelines, seismic lines, mines, have become his backyard.

Cree says it’s harder to live off the land nowadays. Places they would go camping or foraging are now oil wells. One plant, Diamond Willow, Cree says, is hard to find due to all the seismic lines. The willow is important to Fort McMurray First Nation for ceremonial purposes.

Cree says he doesn’t think anything will change. Humans will continue to cut the land and destruction is our nature. Progress is driven by the mighty dollar.

“I don’t think this area will ever rest. We have a lot of old growth trees, we have a lot of water. All those things are what people need. Water, trees, and oil. We’re never going to be able to put the land back. It will always be disrupted or disturbed.”

Although some studies indicate that 3D lines may have less of an impact on wildlife, Cree says they probably cause more damage as the overall amount of area impacted is far larger.

“We’re destroying more area by putting in more lines. I think there’s more damage by putting in the wiggle lines (3D). More animals are disrupted. If anything, I think they should just totally stop.”

Scott Nielsen, a conservation biologist at the University of Alberta, says more research is needed concerning 3D seismic. Due to the amount of lines cut, frequency, and close spacing, he says it’s possible they have a large impact.

“They probably have less effect on some organisms. But it’s still to be determined at what level. How low is low-impact seismic lines? Per kilometre, they’re presumably less than 2D lines, but their densities are extraordinarily high. Even if low, they can add up to a larger impact.” Their effects can be higher if there are also edge effects along seismic lines and into the adjacent forest, such as a change in plant/tree compositions.

However, the Alberta government doesn’t view 3D seismic lines as a disturbance, at least in terms of caribou.

“New seismic lines are minimal disturbance. They aren’t an issue for caribou. We don’t even count them as a disturbance on the landscape,” says Chad Willms, manager of Caribou Range Plans at Alberta Environment and Parks. In a written response from the Alberta Energy Regulator, Kate Bowering, a public policy advisor, says “3D seismic are a very small footprint and re-growth usually occurs within two years.” While Willms did acknowledge the edge effects from seismic, he says more research is needed.

The federal government would not comment on the environmental impacts of seismic lines, saying it’s “a provincial matter.”

However, one thing has changed from the past. Oil companies consult more often with Indigenous peoples on the land. Cree is hired by oil companies. He goes through the bush, in areas where they plan on developing or building a seismic line and looks for old campsites, old ceremonial sites, traditional medicines, and wildlife. He looks to see if the forest is old growth, swamp, or peatlands. If he finds something of interest he ribbons off the area and notifies his boss. Then, it’s up to the oil companies then to decide what to do.

Yet, Cree doesn’t expect much to change. Progress is progress is progress.

“We are going to continue opening up the land and keep building and building. We can’t stop the world. Every morning we wake up and there’s a purpose. We’re told that we have to build something.”

At the end of our conversation, I give Cree a gift of tobacco. He says he’ll take it to a seismic line to ask forgiveness — for what humans have done to the land.

‘This economic downturn is a blessing’

There was a time when Fort McMurray was called a fabled boomtown. Bars were full, hotels overbooked, and even finding a parking spot was difficult. Now, the town is hushed. In June 2014, a barrel of oil sold for $107. In 2015, almost $23 billion was injected into the Canadian economy. However, the glory days didn’t last. In November 2015, oil went for $27 a barrel. The recession came and hit the town hard. It was the worst slump on record since the government began recording data in the 1980s. The fire in 2016, which destroyed more than 2,400 buildings, was the final kick in the stomach. It was nicknamed “The Beast” and was the costliest Canadian disaster at more than $8 billion.

Fort McMurray | Photo by Liam Harrap

While many Canadians view the downturn as negative, some are relieved.

“We consider this a blessing. Economically, it’s not very good. But for the long run, for our traditional life, it’s a blessing,” says Harry Cheechum, land use manager for Fort McMurray First Nation.

Since the downturn, development has slowed. Cheechum has noticed fewer pipelines, roads, and seismic lines being built. While Cheechum acknowledges that development was good for the economy, it made life difficult.

Hunting is important to the Fort McMurray First Nation. Not only for traditional purposes, but for sustenance. Grocery prices in northern Alberta are high. Cheechum says due to the woods being empty of wildlife, people have to travel longer distances. However, some cannot afford the cost of travel.

“We have to drive. It’s cost to us. There are people who can’t afford this. So their traditional lives are shot.” Cheechum says he’s worried that important traditional knowledge will be lost.

Today, oil is $62 a barrel. While growth in the oil sands has slowed, it hasn’t stopped.

The energy company Teck has proposed a $20.6 billion oil sand development between Fort McMurray and Fort Chipewyan. It plans to employ 2,500 people and produce 260,000 barrels per day over a 40-year span. Operations are planned to begin in 2026.

Fort Chipewyan | Photo by Liam Harrap

A land untouched by seismic: Fort Chipewyan

According to a seismic line map of Alberta, there’s one small section in the north that isn’t fragmented – Fort Chipewyan. However, that may soon change.

Perched on Lake Athabasca, one of western Canada’s largest lakes, the town is nestled on top of a stony outcrop. Beside Fort Chipewyan is Wood Buffalo National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, home to the worlds largest free-roaming herd of bison and one of the only nesting grounds of the endangered whooping crane.

The town is one of the only fly-in communities in the province and is connected in the winter by a road when the ground, rivers and lakes freeze.

The golden hour. The stretch of road between Fort McMurray and Fort Chipewyan | Photo by Liam Harrap

A truck pumps water onto the winter road to make thicken ice. For trucks, ice must be over one metre thick | Photo by Liam Harrap

There is little industrial development in this part of Alberta. At least, not yet | Photo by Liam Harrap

“Something is coming. Why spend millions on a new bridge? We’re just a tiny community,” says Vi Martens, who works at the museum in Fort Chipewyan.

Many locals suspect oil. And with oil, comes seismic lines.

Gabe Boruke was born and raised in Fort Chipewyan. Although now retired, he worked for Syncrude as a heavy equipment operator. Although he welcomes the new possibilities that may come to the area, he knows the cost, such as environmental degradation. However, he doesn’t think the town can stop progress.

While Fort Chipewyan has little oil development in the region compared to the rest of the province, Boruke says his home has changed remarkably. The woods are silent, the sky is quiet, and the lake is polluted.

“Everything is gone now. You’d starve to death if you go into the bush. You’d think you can live off the land. You can’t. Even an experienced trapper. No rabbits. No nothing. Everything has changed now. It’s barren country we live in. Not like long ago. No muskrat. No beaver.”

Tracking wildlife populations in northern Alberta is difficult. Scott Nielsen, a conservation biologist from the University of Alberta, wrote in an email that it’s difficult to determine even today how many animals there are in northern Alberta, let alone 50 years ago. He wrote there’s probably fewer caribou and bison, but most other wildlife (except grizzly) are at least as abundant now as before and in some cases more, such as wolves.

“Empirical evidence is hard to come by so local knowledge may suggest something different, but being more of a western scientist myself I like to see a little more evidence than perceptions which to me can be bias regardless of the source as there can be such things as ‘shifting baselines’ where one starts to get used to it being different than it actually was,” wrote Nielsen.

When asked, the Powders, who are from Fort Mckay First Nation, what percentage of wildlife decline they’ve noticed in northern Alberta, Mary interrupted, “We don’t use percentages. That’s a white man thing.” But she’s certain there’s less.

An uncertain future

Fort Chipewyan has had environmental concerns for decades, but Boruke says, no one listens.

The lake used to be a popular fishing spot, but now authorities recommend people limit their consumption. A study in 2010 by the University of Alberta discovered deformed fish in the lake. It also found levels of cadmium, copper, lead, mercury, nickel, silver and zinc exceeded federal and provincial guidelines in melted snow or water collected near or downstream from the oil sands mining.

The effect of the oil sands on the environment is highly controversial. There was little monitoring of the air and water in the region before mining and drilling started. There is a polarized debate about what is considered a “natural” occurrence of petroleum deposits in lakes and rivers.

However, for people that have lived in the region for generations, there’s little doubt of the change.

Boruke is uncertain about the future of Fort Chipewyan. If oil and gas move north, it’s likely more seismic lines will be built as the underground would need to be mapped to locate bitumen or natural gas deposits. The area could be opened to in-situ drilling or more oil sands surface mining.

Mike Doyle, president of the Canadian Association of Geophysical Contractors, says more 3D seismic lines will probably be built in northern Alberta, in particular between Fort McMurray and Fort Chipewyan. Resulting in more forest being cleared, the landscape further impacted, wildlife pushed further away, making hunting and trapping more difficult. The unblemished landscape may become fractured and segmented, further disrupting Indigenous peoples’ traditional lives forever. They may have to go even further afield to hunt, fish, and trap.

“It’s only been 40 to 50 years since they started and everything has changed. What’s going to happen in the next 50 years with the oil companies?” asks Boruke as he scratches the head of Baby Girl, the mother of the litter of puppies.

‘There’s nothing here for my kids’

Edward Marten, a youth educator in Fort Chipewyan, says it all comes down to water. The north is drying up. Like many in the community, he believes the land is polluted. Sometimes in the winter, he says, yellow snow falls from the sky. They used to drink water from the lake, now no one does.

For Martins, he says the future for Fort Chipewyan is grim.

“I’m scared for my grandkids. I don’t want my grandkids to come here and live here. Sure, it hurt me. I cried for them. But it’s good for them. It’s the best choice they made to stay away.”

Marten says there’s nothing for them in Fort Chipewyan, only death.

The UNESCO report on Wood Buffalo includes 17 recommendations, such as suggestions to work more closely with First Nations, conduct studies on water flow and improve monitoring.

Queenie Gray is an ecologist at Wood Buffalo National Park, she says that the park unfortunately is in a “bad location”. It’s downstream from the rest of the province, such as farmers fields, oil sands, and cities.

“It’s not from the park itself. It’s from what’s happening around the park. We’re just in a bad place.”

Gray says that while it would be sad to lose the UNESCO designation, the park itself wouldn’t necessarily change. It would just have fewer letters behind its name and all the prestige that goes along with it. UNESCO World Heritage Sites are designated as such due to their historical importance to the “collective humanity.” There are 1,073 sites worldwide.

“It would still be a national park. Maybe not a heritage site designation, which would be sad, but it would still be protected to the same level as it is now because protection is offered through the national park system,” says Gray. If more seismic lines are built in the area surrounding the national park, it could make the UNESCO designation harder to keep.

***

We stop at the tree with a whiskey bottle on a branch to give thanks for a safe journey. It’s tradition, says Duperron. The ski-doo trail is bumpy and travel is slower than usual. Dupperon curses.

“When I was here a couple weeks ago, this trail was smooth. They’ve ruined it!” He’s referring to other snowmobilers. They didn’t drag a snow groomer behind them, which collect and flattens snow behind the machine. It keeps the path smooth.

We get back on our sleds and soon come to an intersection. Dupperon turns right. We follow.

“In 16 years, I’ve never seen any tracks lead down that other line.” We zip down our endless line, following it into the sun.

***

“It’s funny, because a number of these individuals consider themselves to be conservationists and interested in helping wildlife but they aren’t very forthcoming in giving up a bit to let that happen. They want their access,” says Stan Boutin, professor of population ecology at the University of Alberta.

A key issue that hampers vegetation recovery along seismic lines is their continual use by trappers, hunters, and recreationalists.

While Dupperon says most seismic lines in this part of the province are rarely traveled, he knows that isn’t so for the rest of Alberta.

In areas near urban centres, he says it makes sense to limit all-terrain vehicle use on some seismic lines to allow them to regrow. However, it’s important, at least in his area, to keep them open.

“Right now, we need those seismic lines. We need more access. And it would be a wonderful place to take people and show them how to live with nature. Not try and kill it.” He wants people to see his trap line, show them nature and hope they appreciate it.

“If one of my clients I take hunting doesn’t respect an animal, such as taking a triumphant photo with their foot on its head, when they call back next year, I tell them I’m booked. Even when I ain’t.” Dupperon says it’s important to respect an animal that has given its life for you.

“This year, all of a sudden, I have double the amount of fur. I don’t know why. I’m still learning. I send samples to biologists. I keep journals. I’m out there to help populations. I’m not just out there to kills things.” Last year, using 150 traps, Dupperon caught 33 pine marten. This year he caught 46.

In a plane near Fort McMurray, two summers ago, I fly above the surface mines of the oil sands. Below, trucks the size of houses sift and transport bitumen. The ground is brown. The lakes are brown. Even the clouds are brown. The mines take up an area the size of Edmonton and then abruptly stop. There’s a clear border of forest. We keep flying.

“There’s no human footprint in northern Saskatchewan, there’s no deer there. That’s a place we predict they should be doing well. And low and behold they are,” says Boutin. Caribou numbers in northern Saskatchewan are healthy. However, it’s unknown how many are in the province. There are many fewer seismic lines in northern Saskatchewan than Alberta.

Reaction at the caribou range draft meeting in Edmonton suggests that while most Albertans are concerned about caribou, they aren’t willing to sacrifice jobs or the economy. It’s an old story.

Science suggests it comes down to undisturbed habitat. Without it, caribou won’t survive. It’s difficult to have flourishing oil and gas, logging, mining, and caribou populations. Something probably must be sacrificed. The Alberta government’s decision to suspend its draft caribou plan suggests it isn’t willing to risk the economy to help an iconic Canadian species that’s in trouble. Another part of the old story. The plan was meant to save caribou, but instead its been delayed. Again. As a result, the Alberta government may decide not to restore, replant, or reclaim seismic lines. Now, caribou must fend for themselves. And science suggests they aren’t very good at it and will ultimately fail.

Some are concerned that while caribou are regarded as a threatened species, it’s still unknown how many are left in the province. Perhaps, as Dupperon suggests, caribou in some areas may be doing well and in others not. Regardless, not having a firm grip on caribou numbers makes it harder to convince the public that something’s wrong.

Even if all seismic lines in the province were replanted, it doesn’t guarantee caribou recovery. Possibly by the time the lines are reclaimed, there will be no caribou left. Restoring seismic lines does not solve the problem of high wolf populations. While they may not be able to traverse the province as easily, wolves will still be present.

Although some say caribou are doomed anyway because of climate change, caribou populations in northern Saskatchewan are healthy. It makes sense as there is little human disturbance and few seismic lines. This suggests that human disturbance and the decline of caribou are intertwined.

However, seismic lines do provide a valuable service. They offer access to the land for trappers, researchers, hunters, industry, and even forest firefighters. Without them, going into the woods would be harder. They offer a large benefit but come at a cost.

While 3D lines are narrower, meander, and remove less timber, it’s possibly wrong to assume they have less of an impact. They are packed closer and more numerous, which results in a larger human footprint than previous 2D lines. More research is needed regarding the impact of 3D lines and their influence on the landscape.

Without the plight of caribou, restoring seismic lines probably wouldn’t be an issue. However, reclamation goes beyond caribou. Seismic lines cause vast changes. They influence wildlife populations, flora, insects, carbon storage, permafrost, and Indigenous peoples use of the land. Indigenous people’s traditional way of life has been disrupted. The lines have opened the land and, in some places, have emptied the woods of wildlife. Pollution has crept into the woods. Indigenous people must go further to hunt and gather traditionally important plants. In some cases, they move away entirely, leaving their ancestral lands. A forest that’s usually an entanglement of chaos, now has seismic highways. It’s been forever changed. Seismic lines were never meant to be permanent, but unfortunately, they are.

Like seismic lines, the oil industry is here to stay, as it has invested billions in northern Alberta. It is a pillar of the Canadian economy. Restoration of seismic lines is costly and even if it’s only done in areas deemed to be the most important for caribou, success might not be possible. Reclamation, particularly in peatlands, which is the most critical habitat for caribou, is still in early stages and not well understood. It’s hard to restore a landscape in a few decades that took thousands of years to develop.

With climate change, it’s likely that large-scale forest fires will become more common, destroying old growth forests that are rich in the lichen favoured by caribou. Forest fires might even destroy forest that cost millions to restore. Caribou are not starving but are declining due to habitat fragmentation and predation.

The long-term survival of caribou doesn’t look good. As more forest is cleared, and the oil industry grows, caribou have fewer places to retreat. Even if development is halted, the damage is done. Seismic lines have been around for decades, their construction so unfettered that it will be difficult, if not impossible, to reverse the damage. Perhaps it would be better to focus resources on areas with strong caribou populations, such as in Saskatchewan, to prevent a similar seismic dilemma, as in Alberta.

View from Dupperon's trapping cabin | Photo by Liam Harrap

“

When asked what he’d like the Alberta government to do about seismic lines and caribou, Dupperon says, they should talk with the people that work on the land.

“If there’s something going on with the caribou, we’ll see it. If there’s something going on with the wolves, we’ll see it. It’s no different than you going into your house and noticing something missing from your living room or kitchen. If something changes, we see it. Because this is our living room. If someone moves the couch, we’ll notice.” Other than seismic lines, there’s little industrial development, such as oil drilling, mining, or logging in the Caribou Mountains. It’s one of the least disturbed

As we park in his driveway, Dupperon says he will continue to fight the Alberta government. It’s important that seismic lines stay open, and it wouldn’t hurt if they built more.

“It makes me feel that the people who are being paid by the Albertan citizen have forgotten that they work for us. And they should work with us and not be dictating how things should go. We don’t work for them. They work for us. They need to remember that.”

As we leave the truck, there’s the sound of his galloping horses. A dog runs up, excited to see his master. Erin, Dupperon’s wife, has left us cabbage rolls in a casserole dish made with moose meat. For Dupperon, this will never be home. His home is in the bushes, in a cabin without plumbing, an outhouse for a toilet, and seismic lines for a driveway.