Inuktut at a crossroads

Inuit in Canada are in a race against time to save their language

Inuktut Aqquti Akulliriik

ᐃᓄᒃᑐᑦ ᐊᖅᑯᑎ ᐊᑯᓪᓕᕇᒃ

By Kassina Ryder Davidson

A blizzard delayed Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s arrival in Iqaluit in early March.

For a group of Inuit gathered at the Frobisher Inn in Nunavut’s capital, it was just one more day added to a lifetime of waiting for an apology they hoped would close wounds that time hasn’t healed.

As he made his way through the packed conference room, Trudeau paused to shake hands with many of those in attendance before taking his place at the podium.

“Ullaakkut,” he said in Inuktitut, meaning “Good morning.” It was a respectful nod to the main local language before the prime minister delivered his official apology. Trudeau was there to acknowledge the horrifying way the federal government treated Inuit stricken with tuberculosis from the 1940s to the 1960s.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau apologized on March 8, 2019 for the devastating impact of government policies on Inuit families during Canada’s tuberculosis epidemic from the 1940s to the 1960s. To this day, many Inuit don’t know what happened to their loved ones after they were sent south for treatment. [Photo courtesy of Adam Scotti, PMO]

A cross stands in the Iqaluit’s original graveyard near Koojesse Inlet in Iqaluit, Nunavut. Though Inuktut is the language of the majority of the population, it is not the language of public services, such as health care. A lack of Inuktut in health care and police services are believed to be factors in three recent deaths in the territory. [Photo © Kassina Ryder Davidson]

By 1956, an estimated one-seventh of the country’s Inuit population was in southern Canada being treated for TB. Many never came back. The families of those who succumbed to the lung infection were often never told that their loved ones were dead, let alone where they were buried.

Trudeau’s March 8 apology was unquestionably an historic day for Inuit, yet his words also betrayed an enduring linguistic inequality that Inuit not only experienced in the past, but continue to face today.

“Without their consent, Inuit were screened,” Trudeau told the crowd. “Anyone thought to have TB was sent south to cities like Hamilton and Edmonton, for months or years of treatment in a sanatorium where almost no one spoke Inuktut.”

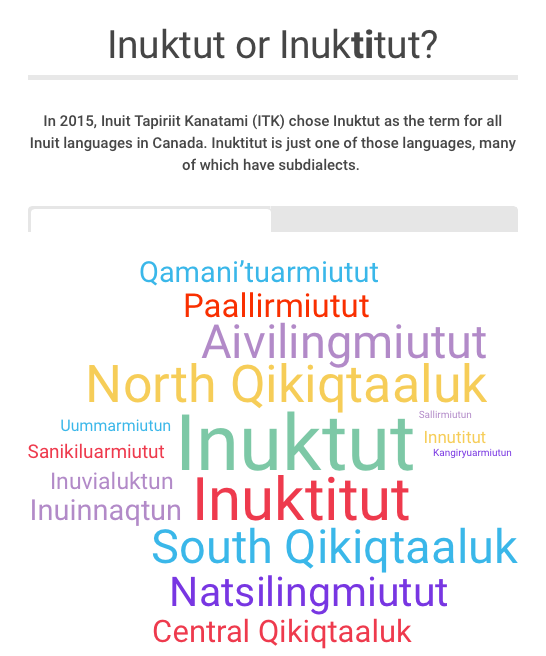

“Inuktut” is the term for the family of Inuit languages in Canada; the Inuktitut dialect is generally spoken in Iqaluit. Trudeau’s simple act of voicing an Indigenous greeting commonly heard in the territory was a meaningful gesture — but also a reminder of the historical discrimination and neglect that has left the Inuit language in a such a fragile state today.

In fact, much of the prime minister’s apology focused on the absence of the Inuit language in the health care system decades ago. But the situation he described as a wrong of the past has persisted into the present. The same cultural disconnect happens every time Inuit require health care today in Nunavut, where few frontline health care workers speak Inuktut.

The year 2019 is the United Nations International Year of Indigenous Languages. But you wouldn’t know it in Inuit Nunangat, the collective term for Inuit regions in Canada. Here, the fight for Inuktut has been quietly waged for decades, and victory seems as elusive as ever.

Note: The size of each dialect name is intended to provide a rough estimate of the number of speakers, but is not an exhaustive list of dialects in Inuit Nunangat. Data source: Inuktut Tusaalanga.

Without urgent action and adequate financial support, the battle will inevitably be lost. The rate of language decline in the Inuit population, currently about one per cent per year in Nunavut, is at risk of accelerating in the coming decades until there are no Inuktut speakers left to keep it alive.

But there’s still time to turn things around, advocates say. Together, Inuit throughout Canada are pushing back against the federal government’s long and ongoing record of failed support for their cherished language.

This is a story of tragedy, dedication and hope, one that has been unfolding in disparate locales across great spans of time. For untold thousands of years until about a century ago, all Inuit living across Canada’s North — as well as their ethno-cultural cousins in Greenland, Alaska and Siberia — were unilingual speakers of one of a handful of ancient “Eskimo-Aleut” languages with many regional variations. But since the era of continuous contact with European newcomers began about 100 years ago in Canada, Inuktut has been under unrelenting threat. Today, it faces a full-blown crisis.

The scenes that illuminate Inuktut’s struggle to survive range from the UN headquarters in New York, where an Inuk leader recently made history by addressing the world in her native tongue; to Greenland, which has witnessed the remarkable renaissance of a sister language called Kalaallisut; to Iqaluit, where a tuberculosis patient’s senseless death — in 2015, not 1955 — has been linked to a lack of Inuit-language health services.

The fight for Inuktut is about more than preserving heritage and strengthening cultural connections. For Inuit in Canada, it can be a matter of life and death.

At current rates of decline, by the year 2051 only four per cent of Nunavut households will include people who speak Inuktut

Day(s)

:

Hour(s)

:

Minute(s)

:

Second(s)

Life and death

Aluki Kotierk, president of Nunavut Tunngavik Inc., discusses her objection to the term “preserve” when talking about Indigenous people and language. [Video by Kassina Ryder Davidson]

Aluki Kotierk is the president of Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. — the organization responsible for legally representing Inuit in Nunavut — and a crucial voice in the ongoing fight for Inuit language rights. Kotierk, an Inuktut-speaker originally from the central Nunavut community of Iglulik, is especially outspoken about the potentially deadly consequences of living in a territory where health care workers don’t speak the language of the people.

“I think it creates a dangerous life-and-death situation for unilingual Inuktut speakers who are unable to access essential health care services,” she said. “They are kind of disabled in their own homeland.”

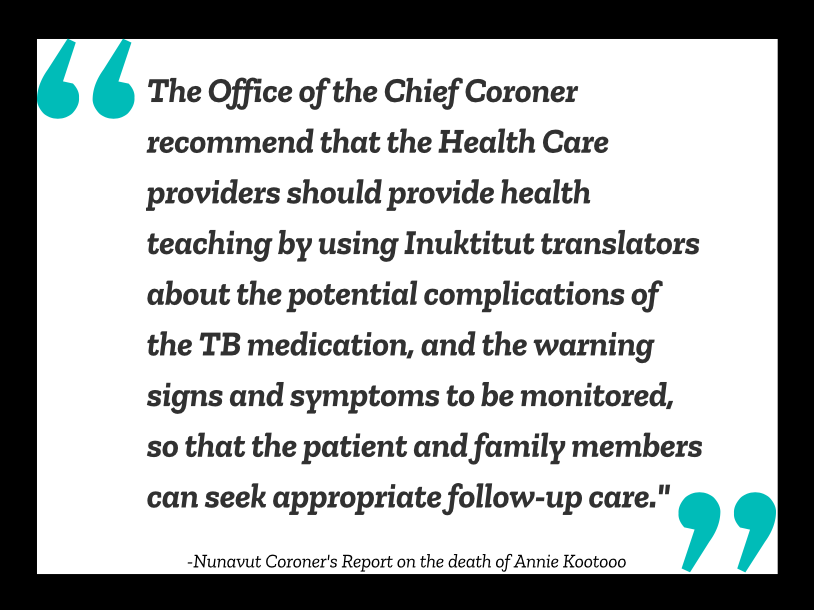

The risky situation Kotierk describes is no exaggeration. In 2015, Iqaluit elder Annie Kootoo died after the drugs she was taking to treat her tuberculosis caused liver failure. For more than a month, she had complained to health care workers in Iqaluit about worsening symptoms, but the signs of trouble were ignored until her condition became so dire that she was airlifted to the Ottawa General Hospital. She died four days later.

Kootoo’s family immediately spoke out about how they believed having Inuktut-speaking health care workers could have saved her life. Providing information in Inuktitut about the potential complications of her TB medication topped the list of recommendations in a coroner’s report investigating the neglect and oversights that led to Kootoo’s death. The second recommendation included providing patients and family members with written instructions in English and Inuktut.

The sick aren’t the only ones at risk when essential services can’t be provided in Inuktut. In March, the family of 20-year-old Kunuk Qamaniq launched a lawsuit against the RCMP after he was shot and killed by police in Pond Inlet, a community about 1,000 km north of Iqaluit on the northern tip of Baffin Island. His family argues that Qamaniq’s death was partly the result of the RCMP’s neglect to recruit Inuktut-speaking officers. As of last July, there were only four Inuit RCMP officers and one Inuit Special Constable in all of Nunavut, which encompasses an area three times the size of Saskatchewan.

A lack of Inuktut-speaking employees was also highlighted in a 2018 Senate report on Nunavut’s search-and-rescue operations. The report,

titled When Every Minute Counts, found that none of the staff at the federal Marine Communications and Traffic Services office in Iqaluit could speak Inuktut, which meant anyone making an emergency search-and-rescue call had to speak either English or French.

Even fundamental doctor-patient confidentiality is constantly undermined in Nunavut, where unilingual Inuktut speakers require friends or family members to interpret during medical appointments. In 2016, the territorial Office of the Languages Commissioner investigated Iqaluit’s Qikiqtani Regional Hospital and found that the hospital’s interpreters weren’t being trained in medical terminology and were frequently unavailable. In some cases, staff had to ask other Inuktut-speaking patients — often complete strangers — to provide interpretation for individuals who didn’t have a friend or family member with them.

“What we need to do,” said Kotierk, “is work really hard to create spaces and pockets where unilingual Inuktut speakers can walk around doing normal, regular day-to-day things with dignity and not have to rely on individuals in their family who are not trained as interpreters.”

Nunavut is a special place when it comes to language, Kotierk said. It is the only jurisdiction in Canada where the majority of residents don’t speak English or French. Today, Inuit account for about 85 per cent of Nunavut’s population of 35,580. Of that number, 65 per cent identify Inuktut as their mother tongue, according to the most recent data from Statistics Canada. But that number is rapidly declining.

Nunavut is just one of the areas that make up Inuit Nunangat, the vast Inuit region of Canada that also includes Nunavik in northern Quebec, Nunatsiavut in Newfoundland and Labrador and the Inuvialuit Settlement Region in the Northwest Territories. In total, Inuit Nunangat is made up of 51 communities spread over a massive 35 per cent of Canada’s land mass, resulting in at least a dozen distinct Inuktut dialects, including Inuktitut in Nunavik, Inuttitut in Nunatsiavut, Inuvialutktun in the ISR and Inuktitut and Inuinnaqtun in Nunavut— many of which have subdialects.

Within Nunavut there are seven major dialects, including Inuktitut and Inuinnaqtun, most of which are deteriorating at different rates.

%

English use in Inuit households in Nunavut in 1991

%

English use in Inuit households in Nunavut in 2011

Ian Martin, an associate professor at York University who has spent two decades studying Nunavut’s education system, is the author of several reports on Inuktut language policy. He contributed to Nunavut’s first bilingual education strategy and to Justice Thomas Berger’s Conciliator’s Report on the Nunavut Project in 2006 before working on the Kitikmeot Inuit Association’s Language Revitalization Strategy in 2011-2012.

In a 2017 report titled, Inuit Language Loss in Nunavut: Analysis, Forecast, and Recommendations, Martin found that Inuktut use in Inuit homes in Nunavut dropped from 76 per cent in 1996 to only 61 per cent in 2011, while English use increased from 28.5 per cent in 1991 to 46 per cent in 2011. Mother-tongue Inuktut speakers dropped from 88 to 80 per cent from 1996 to 2011. Within 32 years, Martin estimated, only four per cent of households in Nunavut will include anyone who can speak Inuktut.

This year marks the 20th anniversary of the creation of Nunavut, but the once-heralded vision of Inuktut as the prime language of public service in an Inuit homeland is still just that — a vision.

Nunavut split from the Northwest Territories and became its own territory on April 1, 1999.

At the time, strengthening Inuktut was identified as a key priority upon creation for the new territory. But two decades later, English has replaced Inuktut in most aspects of daily life in Iqaluit, the territory’s political and economic centre with a population of about 7,700.

Language funding disparity

Nunavut has three official languages at the territorial level, Inuktut, English and French. But unlike English and French, Inuktut doesn’t have federal official language status.

Under Canada’s Official Languages Act, the federal government is obligated to fund minority language programming in either English or French (i.e. English- language funding in Quebec and French language funding in every other province and territory).

But even though Inuktut, with 23,225 speakers, is the majority language of taxpayers in Nunavut, it receives about the same level of federal funding for public services as the minority French population of about 630 speakers.

In the latest four-year Canada-Nunavut funding agreement, $15.8 million was earmarked for Inuktut while French will receive $14.2 million, which in 2019 provides about $219 for each Inuktut-speaker compared to $6,984 for each French speaker.

The money helps fund Iqaluit’s École des Trois-Soleils, the only French- language school in the territory, which opened in Iqaluit in 2002 and teaches students from Kindergarten to Grade 12.

But Nunavut does not yet have a single school devoted to educating students in the Inuktut language.

As of 2016, there were 11 out of 27 schools in the territory providing bilingual English-Inuktut education from Kindergarten to Grade 3, according to a report from the Office of the Languages Commissioner.

Though French receives drastically more funding than Inuktut, Kotierk pointed out that French speakers in the territory also experience inequality when it comes to essential services. The goal isn’t to pit one language against another, but rather to equalize funding so that all languages can thrive.

Federal funding for Inuktut would need to be at least $700 million over four years in order to adequately fund services on a per capita basis, Kotierk estimated.

A spokesperson from Canadian Heritage did not provide an answer as to why Inuktut and French receive similar federal funding when there are thousands more Inuktut speakers than French in Nunavut.

“The Government of Canada has a legal obligation to fund costs for French-language services in the three territories,” the emailed response stated. “The Government of Canada also negotiated agreements with all three territories to provide support for Indigenous languages at a comparable level of funding to French-language services.”

Recognizing Inuktut as a founding language of Nunavut is a first step toward securing adequate funding to support its protection, as Kotierk outlined in her address last April in New York to the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, a precursor event to the 2019 International Year of Indigenous Languages.

Kotierk used her three-minute platform to deliver a powerful speech about Canada’s culpability in trying to eliminate Inuktut and its responsibility to support the language today.

“The nation state of Canada has played a historical role in actively working to strip Indigenous people of their culture, including their language, through residential schools,” she said in her address. “This is no different for Inuit.”

Source: Is Nunavut education criminally inadequate? An analysis of current policies for Inuktut and English in education, international and national law, linguistic and cultural genocide and crimes against humanity. Pg. 37. Nunavut Tunngavik Inc., April 2019.

The right to use Indigenous languages and to establish education systems in those languages is enshrined in Articles 13 and 14 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). Kotierk referenced these rights in her address, pointing out the shocking discrepancies in language support for Inuktut in Nunavut’s education system compared to English and French. According to Kotierk’s numbers, there are 9,300 Inuktut mother-tongue speaking students, compared to only 430 English mother tongue students (who are mostly non-Inuit) and about 80 French-speaking students.

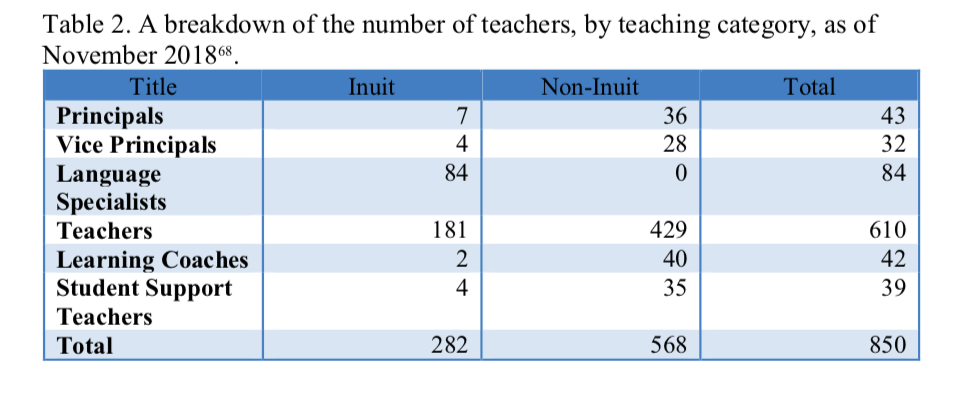

“There are actually more English teachers than there are English students in our schools,” she told the delegation. “So the reality is our Inuit children do not see themselves reflected in the majority of the curriculum. Our Inuit children do not see themselves reflected in the majority of the teachers. Our Inuit children do not hear their language, Inuktut, used in the majority of their classrooms.”

Bill C-91

Kotierk said it was important for her to use her platform at the UN to show the world that Canada, which opposed UNDRIP for nearly 10 years before finally adopting it in 2016, is still failing to follow through with its commitments to Indigenous people.

“I think many populations around the world sometimes look to Canada as very progressive,” she said during an interview at NTI’s office in Iqaluit. “It was important for me to point out that even within Canada, as Indigenous populations, we are struggling with our federal government and trying to achieve self-determination that is yet to be achieved.”

The struggle continued this February when the federal government unveiled its much-anticipated national Indigenous languages legislation, Bill C-91. While the Métis Nation and Assembly of First Nations applauded the bill, Inuit organizations were deeply disappointed.

Bill C-91 didn’t include any Inuktut-specific provisions, a fact that came as a shock to Inuit leaders who had worked on it, including Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami president Natan Obed. ITK, the national organization representing Inuit in Canada, had worked with the federal government to identify priorities and offered several reports, including one titled, National Inuit Position Paper on Federal Legislation in Relation to Inuktut. The paper outlined how multi-year funding agreements between Canada and regional Inuit organizations could finally put Inuktut on equal footing with English and French.

“Inuit Nunangat Language Accords should utilize a funding formula that respects the varying status of Inuktut in each region; resources allocated for Inuktut should be equitable in view of resources allocated for French in those jurisdictions,” the paper stated.

Natan Obed, president of ITK, addresses the House of Commons heritage committee on Feb. 25, 2019. Obed and other Inuit leaders were shocked and disappointed that the highly anticipated federal languages bill failed to include the Inuktut-specific content they had expected. [Video courtesy of ParlVu]

Aluki Kotierk, president of NTI, addressed the House of Commons heritage committee on Feb. 26, 2019. She, too, expressed frustration that Bill C-91 had failed Inuit. Kotierk delivered her address in Inuktut. [Video courtesy of ParlVu]

Instead, the proposed Bill C-91 includes establishing a government-appointed Commissioner of Indigenous Languages and makes no mention of any long-term funding possibilities.

Obed testified before the House of Commons heritage committee on Feb. 25 and pointed out that none of the “countless hours” of work contributed by Inuit had been incorporated into the bill.

“If it was truly co-developed, there would be segments of this act that we could point to and say, ‘These were the segments that Inuit wanted within this,’ ” he told the committee.

In her address to the committee on Feb. 26, Kotierk, speaking in Inuktitut, called the proposed Bill C-91 a “largely symbolic effort” that failed to make any funding commitments or outline a duty to provide federal essential services in Inuktut.

To have teeth, Kotierk said, the bill would need to be accompanied by a stand-alone federal Inuktut Act that would recognize it as both an original language of Canada and the first language of Inuit Nunangat residents. Legislative measures should also include real commitments to fund essential federal services and programs in Inuktut, Kotierk insisted.

“I can say generally what we’re looking for is that there be recognition of Inuit languages as the original language of Inuit Nunangat, that we’re expecting to be able to receive essential services in Inuit languages, and we’re expecting this would require adequate and equitable funding to be able to provide for that,” she told the committee.

On June 14, the Senate Standing Committee on Aboriginal Peoples adopted Bill C-91 and included some – but not all – of the amendments Inuit had put forward. As of June 17, ITK was still pushing for more Inuktut-specific measures before the bill’s finalization.

“It is regrettable that not all of the well-reasoned and thoughtful considerations put forward by Inuit were included by the Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples,” the organization said in a statement. “ITK encourages Parliamentarians in the House of Commons to include all Inuit recommendations in consideration of the Senate amendments in the final passage of Bill C-91.”

A Look Down “the Road not taken”

This April, Kotierk again highlighted Inuktut at the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, this time calling Nunavut’s education system “cultural genocide.”

“This report has analyzed domestic and international law and determines linguistic and cultural genocide and crimes against humanity are being committed.”

– Aluki Kotierk, address to the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, April 22, 2019.

Last September, NTI commissioned a report titled Is Nunavut education criminally inadequate? An analysis of current policies for Inuktut and English in education, international and national law, linguistic and cultural genocide and crimes against humanity.

Inuit in an English-based school system instead of one geared to their needs are set up to fail, the report stated, a situation that contributes to Nunavut’s elevated high school drop out and truancy rates and subsequently, relatively high poverty and extreme social inequality.

“Education in Nunavut has a history of cultural genocide, linguicide, econocide and historicide, and this continues today” said Kotierk in a press release. “Inuit children receive the majority of their education in the dominant languages instead of their mother tongue. This constitutes cultural genocide.”

The report also challenges the idea of English as uniquely indespensable in a modern world and its widespread adoption as harmless.

“English is fraudulently marketed as a universal need, a lingua nullius that can be used for all purposes everywhere,” the report stated. “English is promoted as though it is the only language you need in international affairs, an argument that falsely makes other languages invisible.”

In 1984, the then-Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development (DIAND) published a report called The Cost of Implementing Inuktitut as an Official Language in Nunavut as part of the preparations for the creation of Nunavut.

The federal study determined that it would require an initial $21.5 million (the equivalent of about $45.4 million in today’s dollars) for “start up” costs in every territorial government department, and an additional $8.4 million ($17.7 million today) in annual maintenance costs.

However, the federal government shelved plans to fund an Inuktut-centred territorial government with promises of resurrecting the idea in the future.

But the clock is still ticking more than 35 years later.

In his 2017 report on Inuktut’s declining fortunes, Martin called this the “road not taken.”

“Had Canada supported the Inuit language with similar levels of funding as it provides to other provinces for English and French services, perhaps the survival of Inuktut would not be in question today,” he stated in his study, titled Inuit Language Loss in Nunavut: Analysis, Forecast, and Recommendations.

“Canada might also have avoided running afoul of Section 36 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which guarantees ‘essential public services of a reasonable quality’ to all Canadians.”

When Nunavut split from the N.W.T. in 1999, it created its own Education Act, which was passed in 2008. A key component was to be able to deliver English-Inuktut education in all grade levels by 2019-2020. But by 2013, it was obvious that meeting the deadline would be impossible, according to a federal auditor general’s report.

Three years later, Nunavut’s Office of the Languages Commissioner issued a report that found only one school, Kugaardjuk Ilihakvik in Kugaaruk, located in Nunavut’s western Kitikmeot region, was offering bilingual education up to Grade 5.

Its inability to meet the deadline meant the Government of Nunavut had to enact a temporary Interim Language of Instruction Act (LOI Act) in February 2019, which temporarily suspended implementing the portions of the Education Act and the Official Languages Act that related to Inuktut education. The move was necessary to protect the territorial government from possible litigation, government house leader Elisapee Sheutiapik said at the time. In short, failing to comply with its own promises meant the government was vulnerable to possible legal action. However, focusing on delaying bilingual education instead of working toward implementing it was widely criticized as a way the government was shirking its responsibility to Inuktut.

In June, Bill 25, An Act to Amend the Education Act and the Inuit Language Protection Act, was introduced. It proposes delaying Inuktut instruction in schools by 20 years. Inuktut as the language of operation within the Government of Nunavut would also be delayed until 2040. The bill will be discussed again in October during the fall sitting of Nunavut’s legislative assembly.

Canada’s history of language extermination

It should come as no surprise that the territory’s education system is struggling to integrate Inuktut only a few decades after the federal government tried to exterminate the language.

By the 1950s, Inuit children were legally required to attend school and Chesterfield Inlet, a community on the western shore of Hudson Bay in Nunavut’s Kivalliq region, became the home of the first residential school for Inuit, which was run by the Catholic Church.

Canada’s residential school system, funded by the then-Department of Indian Affairs and operated through churches, began in the 1880s, and

A group of students working at their desks in a classroom at Sir Joseph Bernier Federal Day School (Turquetil Hall) in Chesterfield Inlet (Igluligaarjuk), Nunavut, September 5, 1958. First row: Rene Otak (far left); second row: Peter Irniq (far right), beside him is Paul Manitok; third row: Nick Anautinuq (far right); fourth row: Raymond Kalak (second from the left). [© Library and Archives Canada. Reproduced with the permission of Library and Archives Canada.]

the last school officially closed its doors in 1996. Many children were physically and sexually abused in addition to being chronically malnourished and susceptible to illness and disease. At least 3,200 children are known to have died in residential schools, but the actual number is believed to be much higher.

The goal was to assimilate Indigenous children into Canadian society, which meant cutting all connections to their inherited cultures. Speaking any Indigenous language, including Inuktut, was forbidden, a key part of the “cultural genocide” that had occurred in residential schools, according to Justice Murray Sinclair, chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission from 2009 to 2015 and now a member of the Senate.

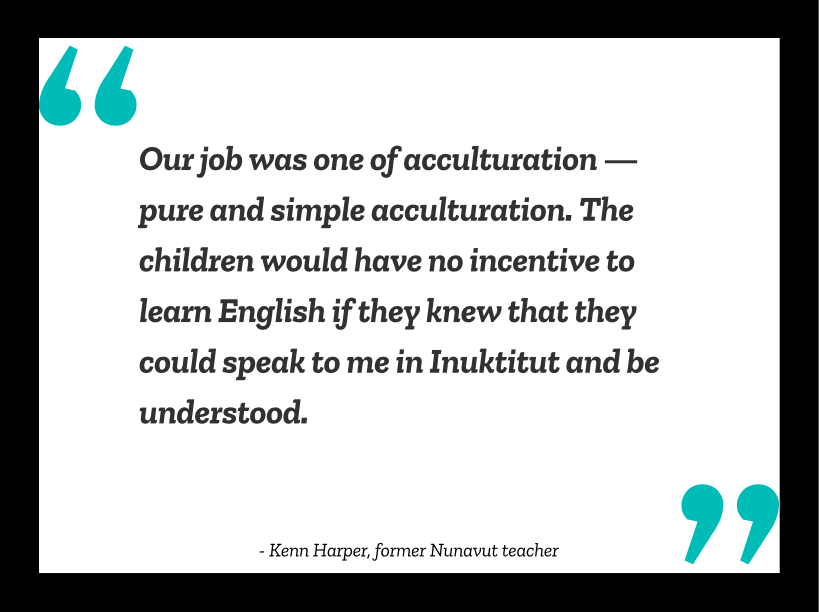

As the years went on and more Inuit in Nunavut transitioned from living on the land to settlements with small schools of their own, Inuktut was not only prohibited in the classroom, but teachers — typically coming from the South — were specifically instructed not to learn the language themselves.

At least one teacher ignored that rule. Kenn Harper, now a well-known author, historian and regular contributor to the Nunatsiaq News newspaper based in Iqaluit, started his career in Nunavut as a teacher in Qikiqtarjuaq, then known as Broughton Island, off the eastern shore of Baffin Island. Harper also lived in Greenland for two years in the 1980s and is now a Danish Knight, after he was appointed to the Royal Order of Dannebrog in 2014 for his work as Nunavut’s Honorary Consul of Denmark.

“At our orientation course here in Ottawa in 1966, we were admonished not to learn to speak Inuktitut,” he said. “Our job was one of acculturation — pure and simple acculturation. The children would have no incentive to learn English if they knew that they could speak to me in Inuktitut and be understood.”

But despite his desire to learn, Harper didn’t master much Inuktitut during his first year in Broughton Island, which he blames on being one of a dozen non-Inuit in the settlement who only spoke English.

“Like most people, I’m lazy and take the easy way out,” he said. “But that year wasn’t a waste of time because my ear was hearing it. My ear was getting ready for it.”

Learning Inuktut became so important to Harper, he applied for a transfer to a smaller community, this time to Padloping Island, located to the east of Baffin Island, which had a population of 35 people. After his wife and son returned south partway through the year, Harper became the only non-Inuit member of the community. Through a combination of listening to reel-to-reel tapes made by Inuit working under the direction of linguist Raymond Gagné in the 1960s, and studying a book by Hudson Bay Company postmaster and linguist Alex Spalding called A Grammar of the East and West Coasts of Hudson Bay, in addition to visiting with locals and attending church, Harper was able to speak and understand basic Inuktitut by late spring of that year.

But it was his own tenacity — he dedicated at least five hours a day to actively learning Inuktitut — that allowed him to achieve fluency. Even in those days, Harper said, it was easy for southerners to avoid learning the language.

“Most of the teachers I knew in Pond Inlet and Arctic Bay and Pangnirtung did not learn Inuktitut,” he said. “Some of them were only there for a year or two but some of them were there for a long time and most of them did not learn Inuktitut, which always perplexed me.”

Fast forward 50 years and Nunavut’s education system is still acting as an assimilation tool in a territory where most educators are non-Inuit. Out of about 850 teaching personnel in Nunavut, only 282 are Inuit. Hundreds more are needed in order to teach in Inuktut from Kindergarten to Grade 12, territorial Education Minister David Joanasie said in a telephone interview from Iqaluit. “We’ve estimated the need to get an additional 450 Inuit teachers for us to be able to deliver a bilingual education system across the territory,” he said. Article 23 of the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement requires government departments to employ a workforce that is representative of the Inuit population of Nunavut, which makes up 85 per cent of all territorial residents.

In his report, Martin slammed the education department for not having an Inuit Employment Plan in place by the time the Education Act was passed in 2008. Without an IEP, any plans for bilingual education “existed only on paper.”

Nunavut Arctic College has a program specifically designed to train Inuit teachers, the Nunavut Teacher Education Program. In his report, Martin explained how the program alone wouldn’t be able to keep up with the demand. Of the average 12 Inuit who graduate from NTEP every year, the department of education only retains about nine. Combined with the retirement of current school staff members, it would take until 2071 to have enough teachers to deliver Inuktut education in all grades.

The department is currently working on an educator recruitment strategy, which could include expanding the NTEP program to more communities, Joanasie said.

The program is now available in nine of Nunavut’s 25 communities. An estimated 23 students are expected to graduate from NTEP this year, the largest graduating class in the program’s history.

But even then, there’s no guarantee these university-educated Inuit will stay in the teaching profession for extended periods of time.

Inuit Language Loss in Nunavut by kassina davidson on Scribd

An inuksuk sits stoic beside an Iqaluit road in June 2018. Markers such as this are a form of language; they are often used to signify good hunting and fishing places, as well as to help with travel. [Photo © Kassina Ryder Davidson]

Iqaluit is a growing city with a population of about 7,700. [Photo © Kassina Ryder Davidson]

Mila Adjukak Kamingoak, MLA for Kugluktuk, a community in Nunavut’s Kitikmeot region, suggested a simpler idea during a legislative assembly session on March 5: use letters of authority to hire Inuit to teach.

The Education Act allows the education department to issue letters of authority allowing Inuit without certification or training to teach in order to temporarily fill vacancies. It’s an idea that has been tried in the past and didn’t work, Harper said. “You wouldn’t try that in English,” he said.

“You wouldn’t grab a guy off the street and say, ‘You speak English?’ ‘Yep.’ ‘Well, we’re going to have you teach English now in our school.’ ”

Nunavut’s school attendance rates add to the problem.

The rate was just 68.2 per cent during the 2016-17 school year, which means that fewer than seven in 10 students in Nunavut who should be in school regularly attended classes.

Certainly, strengthening Inuktut is going to take a huge effort at home as well as in the classroom, Joanasie said.

“I think that’s a big message that I try to impart to Nunavummiut [residents of Nunavut],” he said. “If it’s not being emphasized, if it’s not important, children will pick that up at home and amongst their friends. I think that’s something we need to take a hard look at.”

A recent Statistics Canada report found that in households where both parents speak Inuktut, the language becomes the mother-tongue for nine out of 10 children. In homes where only one parent speaks Inuktut, that number plummets to a mere three in 10.

Ensuring her children can speak Inuktut is a priority for Iqaluit mother Simiga Lyta. She said she has spoken to her children in the language since the day they were born.

“It’s our first language,” she said. “I want them to know it and speak it when they grow up.”

Harper warned against using Iqaluit as the proverbial canary in the coal mine, pointing out that smaller communities on Baffin Island, such as Pangnirtung and Pond Inlet, have better Inuktitut rates than in the capital.

“It’s too easy to get an Iqaluit-centric view of things and think that everything is as bad in Nunavut as it is in Iqaluit, and that’s not true,” he said.

However, there is one consistent danger in every home in every community, according to Harper — English-language television.

“It’s the biggest threat to the Inuktitut language,” he said.

A Writing System For Inuit, By Inuit

Jeela Palluq-Cloutier, executive director of Uqausinginnik Taiguusiliuqtiit, Nunavut’s Inuit Language Authority, says use of syllabics will continue even though the new writing system will use roman orthography. [Photo © Kassina Ryder Davidson]

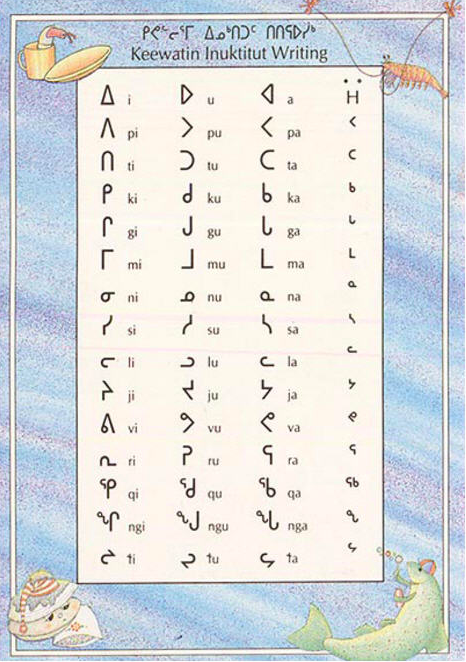

Before writing was introduced, Inuit had an oral culture, with traditions and knowledge passed down through song and storytelling. That began to change as missionaries arrived in the North, bringing the written word with them. Though roman orthography, the 26-letter alphabet used for English and French, had been used in the Nunatsiavut area since the late 1700s, syllabics — the symbol-based writing system invented in the 1840s to teach Cree how to read the Bible — later took hold in other regions.

The syllabics system, which uses characters to represent different vowel and consonant combinations, was primarily used by Inuit in the central and eastern Arctic and in Nunavik (northern Quebec). Inuit in Nunavut’s Kitikmeot region, Alaska, the Northwest Territories, Nunatsiavut (Labrador) and Greenland used roman orthography.

But even using the same writing system didn’t guarantee one group could understand the other. Within each system were myriad spellings and characters unique to each area, prompting the Inuit Cultural Institute to develop a standardized writing system in the 1970s for both syllabics and roman orthography.

Today, that work is being taken even further. In 2012, ITK established the Atausiq Inuktut Titirausiq Task Group, which is made up of language specialists from across Inuit Nunangat who are now developing a unified writing system intended to unite Inuit language speakers across Canada and around the world.

The syllabics writing system uses symbols to represent vowel and consonant combinations. For example, the word Inuktut in syllabics looks like this: ᐃᓄᒃᑐᑦ.

Currently, there are nine different writing systems (both syllabics and roman orthography) representing dialects across Inuit Nunangat. Having one writing system means everything from books and teaching materials to official documents and health care information can all be written in a single script that everyone can understand, no matter what their regional dialect. The system is a way of bringing all Inuktut dialects together as one, growing literacy rates and increasing the number of speakers.

But many Inuit fear standardizing the writing system will mean the decline of these regional dialects and the death of syllabics, both of which form a special part of cultural identity for many Inuit.

Public consultation and education have been vital components in the task group’s work, said member Jeela Palluq-Cloutier, who is also the executive director of Inuit Uqausinginnik Taiguusiliuqtiit (Nunavut’s Inuit Language Authority), which operates as an arms-length public agency.

“When people understand the need for a unified writing system, they’re in support of changes,” Palluq-Cloutier said. “Where we find people are resisting to make any changes are those that do not understand why we’re doing this.”

The new system isn’t favouring one dialect, but instead aims to incorporate what works best for all speakers. However, some regions will have to accept changes.

Inuvialuktun is spoken by about 595 people in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region of the Northwest Territories and Inuinnaqtun, spoken in Cambridge Bay and Kugluktuk in western Nunavut, has about 1,310 speakers. In both of these regions, the letter “y” represents a “yuh” sound (qayaq) while in other communities the letter “j” represents the same sound (qajaq). In Nunatsiavut (Labrador), a capital K represents the uvular sound typical of many words in the Inuit language, whereas this back-of-the-tongue sound is represented by the letter “q” in other communities. The task group chose the latter approach in both cases, which will become the standard.

While the new system will be used in official capacities, such as in government documents and educational materials, that doesn’t mean syllabics will be stamped out, Palluq-Cloutier said.

“We are not abolishing syllabics. People will continue to use syllabics as they do,” she said. “I take my notes in syllabics much quicker than I do in roman orthography, so it’s not going to be abolished.” Having a standard writing system will help solidify Inuktut’s place in the classroom, eliminating dialectal barriers between schools in different regions.

“With a unified writing system, all teaching resources will be available to all the schools and all the teachers no matter what dialect they speak,” Palluq-Cloutier explained.

What’s more, establishing the writing system is an act of Inuit sovereignty and the rejection of colonization, she added.

“The writing systems were given to us and that’s a reason why we have so many different writing systems today. They were introduced to Inuit regions at different times by different people,” she said. “We need to be able to say that this is a decision made by Inuit, for Inuit.”

The Greenland effect

On a city bus in Nuuk, Greenland’s capital and largest city, mothers chat with their children on their way to the Nuuk Center shopping mall while teenagers stare at their phones. The scene could be lifted from any bus in the world on a Tuesday morning in July, with one big difference. Everyone on this bus is speaking Kalaallisut, the Indigenous language of Inuit in Greenland.

For Inuit living in Nuuk today, Kalaallisut (also known as West Greenlandic and traditionally, Inupik) is so much a part of daily life it’s almost impossible to imagine places where the Inuit language is in decline.

Tikaajaat Kristensen, a researcher at Oqaasileriffik, the Language Secretariat of Greenland, remembers the first time she realized there were Indigenous youth who couldn’t speak their language.

As a teenager, Kristensen was part of a United Nations youth delegation made up of Inuit from Greenland, Canada and Alaska. During a break, she and other Greenlandic youth were chatting about their plans for the rest of the day.

“I didn’t really think about how we speak Kalaallisut on a daily basis,” Kristensen said.

“At one point we were in the elevator and just talking about what to do, just speaking Kalaallisut, and suddenly there was this girl from Alaska who was like, ‘I’m so jealous, you can speak your language.’ And we were like, ‘You don’t?’ I just assumed they spoke the same amount as we do.”

Staff at Oqaasileriffik, the Language Secretariat of Greenland, break for lunch on July 10, 2018. From left, Aron Kuitse, Najannguaq Nielsen, Ane-mette Damgaard, Lulu Damgaard, Tikaajaat Kristensen, Paneeraq Nielsen and Camilla Kleemann-Andersen. [Photo © Kassina Ryder Davidson]

What Kristensen describes — an Inuit homeland where everything operates in the traditional language of its inhabitants — is still only a dream in Canada.

In Greenland, an autonomous country of Denmark, about 50,000 of its 56,000 inhabitants can speak Kalaallisut.

Unlike in Iqaluit where English is prominent, Greenland’s capital functions almost completely in Kalaallisut and anyone visiting a store or a restaurant — or more importantly, a hospital — can expect service in the main Indigenous language in addition to Danish.

As of 2012, 20 of the 100 doctors in Greenland were native to the island, which also has hundreds of Greenlandic nurses. Greenland has a university, Ilisimatusarfik, that offers 11 bachelor’s degree programs and four programs at the master’s level. Programs include nursing, teaching, journalism, business and language, literature and media. Though the language of instruction is Danish, many professors and staff speak Kalaallisut fluently.

University in Greenland is free and tuition is covered for Greenlandic students who attend university in Denmark. The country has also had a college dedicated to training Greenlandic teachers for more than 150 years.

In 2012, the teacher training program at Ilisimatusarfik graduated 40 students and according to recent numbers, about 75 per cent of teachers are Greenlandic.

Children begin school at six years old and their first 10 years of education is entirely in Kalaallisut, with Danish introduced as a second language after the first grade.

Comparing Greenland and Inuit Nunangat

It’s easy to see why Greenland’s success is heralded as the example that Inuit in Canada should be working toward, but some say it isn’t a fair comparison.

One major difference is that while Inuit Nunangat is made up of Inuit regions across Canada, Greenland is essentially an independent state within the Kingdom of Denmark. Its status as a country gives it control over much of its internal affairs, including its health and education systems, though not defence and foreign affairs

Its history with the written word also goes back much further in time than it does in much of Inuit Nunangat. More than 40 books, including religious texts, a handbook on midwifery and a housebuilding booklet, had been translated into Greenlandic by the 1850s. Around the same time, the first Greenlandic newspaper, Atuagagdliutit (now known as Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten or AG), was being regularly published in Kalaallisut.

“It was printed here in Nuuk, then travelled with qajaqs (kayaks) around the coast,” said Kristensen. “People could write in and have their submissions in the papers and everything was in Kalaallisut.”

In contrast to Canada, where at various times missionaries introduced different writing systems in different dialects, Greenland had a standard orthography, the Kleinschmidt system (named for its creator, linguist Samuel Kleinschmidt), by the 1850s. The Kleinschmidt system served as the standard orthography until 1973, when it was again updated and modernized, a process that is continuing today to keep up with new technology and concepts.

Like Inuit Nunangat, Greenland experienced colonization. Denmark began its modern colonization of Greenland in the 1720s and Danish was a school subject by the late 1920s. In 1953, Greenland was declared a “county” of Denmark and an educational overhaul began with Greenlandic schools being brought up to Danish standards, saturating the country with both Danish teachers and educational material. By the 1970s, only about 200 of the 700 positions in Greenland’s schools were filled by Kalaallisut-speaking teachers.

Also during this time, Greenland’s young people were being encouraged to travel to Denmark for university.

Puju (Carl Christian) Olsen was one of them.

Olsen was born in Sisimiut, a community about 320 km north of Nuuk, and is known throughout the circumpolar world as an Indigenous language champion. Educated in Denmark in the 1950s, Olsen returned to Greenland with new ideas on how to undo the damage that was being done by Danish colonizers to the Inuit language.

Together with other young people, Olsen began petitioning the Danish government, demanding that school be taught in Kalaallisut.

In 1979, Greenland achieved its Home Rule Agreement with Denmark and Kalaallisut became the language of instruction in every primary school. In 2009, the agreement was replaced by the Act on Greenland Self-Government, which transferred more power from Denmark to Greenland (including, if Greenland eventually chooses, the right to become fully independent from Denmark). It was then that Kalaallisut became Greenland’s official language.

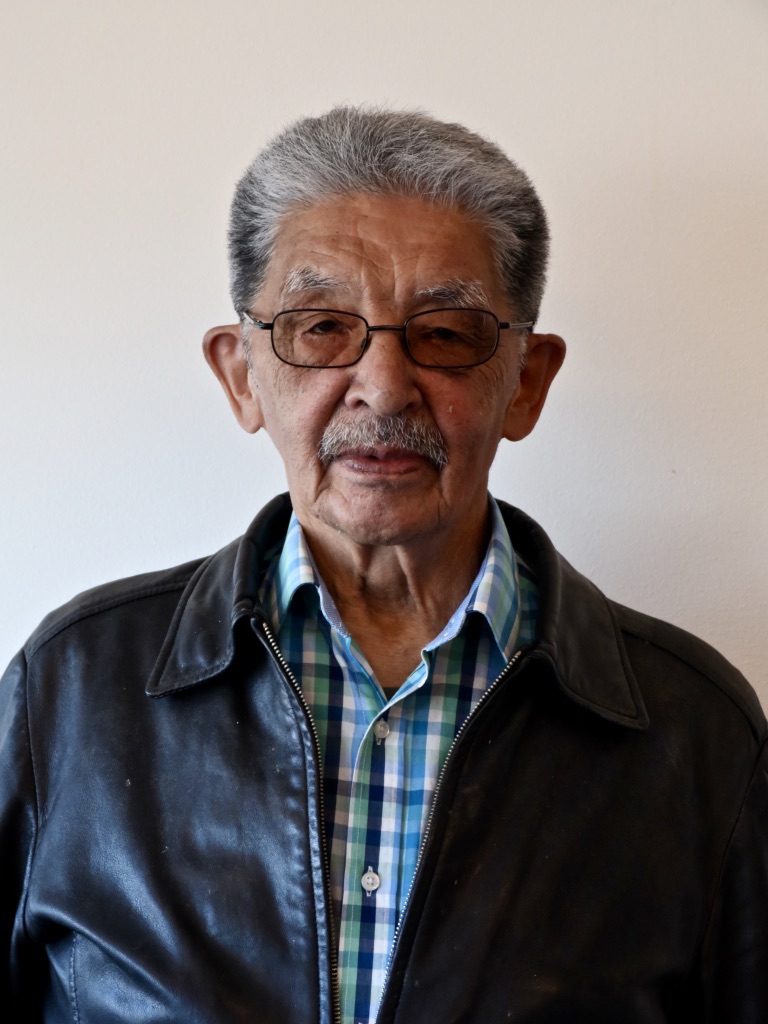

Olsen, a language scholar who is also one of the founding members of the Inuit Circumpolar Council and the University of Greenland, said their success was bolstered by the global cultural rebellion of the 1960s and ’70s, when youth around the globe were challenging authority and trying to change the world.

“I think we were rather enlightened because we went to high school in Denmark and went to university,” he said. “We were very well informed.”

Yet even in the years when Kalaallisut was being overshadowed by Danish in the education system, it was still the language of the people.

Linguistics expert Puju (Carl Christian) Olsen discusses how Kalaallisut is a traditional language that is keeping up with modern times. [Photo © Kassina Ryder Davidson]

Ilisimatusarfik, the University of Greenland, has 11 bachelor’s degree programs and four master’s programs in four institutes: the Institute of Learning, Institute of Nursing and Health sciecne, the Institute of Social Science, Economics and Journalism and the Institute of Culture, Language and History. [Photo © Kassina Ryder Davidson]

Maya Sialuk Jacobsen and Paninnguaq Lind Jensen are traditional tattoo artists from Greenland. Both said teaching Kalaallisut to the very young is key to its success. [Photo © Kassina Ryder Davidson]

Maya Sialuk Jacobsen is from Qeqertarsuaq (Disko Island), a community about 560 km north of Nuuk. Together with Paninnguaq Lind Jensen, from Narsaq, about 465 km south of Nuuk, the women are bringing the practice of ancient Inuit tattooing back to Greenland. Both said the term Kalaallisut is a word born from colonization and instead refer to the language as Inupik.

Jacobsen attended a Danish school in her community and Danish was the language of instruction for the first six years of her education. After Home Rule came into effect, the Danish school was shut down and almost overnight, Kalaallisut was the language spoken in the classroom. Jacobsen said she and other students had some trouble transitioning, such as learning to read and write Kalaallisut, but she also feels that the “Danification” that took place in her early years in school impacted her ability to retain her language. Even so, she said she can understand Inupik and is working on improving her speaking ability. She said being surrounded by people speaking the language is the reason why she was able to understand Inupik, even though she was being educated in Danish.

“It’s definitely a language that is at home, it’s not a language that necessarily was in school,” she said. “So we would speak it in the streets and when we were playing.”

Jensen began attending school in 1996, well after Home Rule, but her school in Narsaq was primarily taught by Danish teachers. Yet Jensen, too, was a fluent Kalaallisut speaker as a child.

“It’s mostly from my grandparents and the kids I was playing with on the street where I learned to speak Inupik,” she said.

As she got older, Jensen said she began losing her language in favour of Danish, but after several years of re-learning, she was able to regain fluency.

“I have done anything I could to take back the language and now I talk Inupik fluently,” she said. “But, of course, it’s way easier for me because I’m surrounded by people who speak Inupik and most of my family speaks Inupik, too.”

But despite its health, Kalaallisut is also experiencing change. Young people sometimes speak in sentences that combine Danish and Kalaallisut, which Jacobsen said is diluting the strength of the Indigenous language.

“They are altering the grammar of the language, they’re making it easier,” she said. “Inupik is a very complex language where even your voice level and your grammar will change when you age because it will show your status as an elder person, or if you’re young, if you’re a woman, if you’re a man.”

Programming that encourages young children to spend time with elders is a great step toward teaching younger speakers the unadulterated form of the language, Jacobsen added.

Downtown Nuuk on a July evening. In the city, Kalaallisut is everywhere. [Photo © Kassina Ryder Davidson]

Click on the tab above to listen to KNR (Kalaallit Nunaata Radioa), Greenland’s public broadcaster. Though some music and interviews are in other languages, the majority of its content is in Kalaallisut.

The country’s history with the written word, as well as the use of Kalaallisut in the media and in music, are the foundations of Greenland’s high retention of the original language, Olsen said.

Today, Greenland has a thriving Indigenous music scene with artists producing songs with Kalaallisut lyrics. The recordings are popular with Greenlanders at home and abroad, Jacobsen said.

“We listen to Greenlandic music every day,” she said. “Even Greenlandic people who live in Denmark like I do, we listen to Greenlandic music every day.”

The country’s public broadcaster, KNR (Kalaallit Nunaata Radioa), produces television and radio programs in Kalaallisut, as well as in Danish.

As in Canada, there are different dialects in Greenland, but KNR uses the standard orthography, ensuring consistency.

“News radio and news television are very helpful for Greenland because through this you can introduce common usage,” Olsen said.

Adaptability is another factor in Kalaallisut’s success, added Olsen.

One of Oqaasileriffik’s many roles is to adapt Kalaallisut to a changing world. Staff created computer software that automatically converts text written in the old orthography (before 1973) into the updated orthography, and computers are equipped with a Kalaallisut version of spellcheck. They also invent new words and add them to the ever-growing Kalaallisut dictionary, such as the Kalaallisut word for rocket: avataarsualiartaat.

“Greenlandic language is not limited to Inuit culture. The language is capable of expressing anything,” Olsen said. “You can even land on the moon speaking Greenlandic.”

Though Greenland sets the bar high, the country still faces linguistic challenges. A big question is whether Greenlandic students who only speak Danish as a second language are disadvantaged in the global community. Another debate is whether English should replace Danish in order to expand opportunities for Greenlanders in a world where English is often considered the closest thing to a global lingua franca.

But one thing is clear; strengthening an Indigenous language requires adequate financial and policy support from government, as well as grassroots engagement. And even the smallest efforts can have big impacts.

“I think parents need to be brave enough to use the little language that they have and give it to their kids,” Jacobsen said.

“They just need to add on, every day, a little word here, a little understanding of a phrase there. Suddenly you can understand an entire story or an entire song. Suddenly, it’s there.”

The Path Forward

In Canada, Inuit are also developing ways to strengthen Inuktut in a changing world. Last year, Facebook announced that it was working on making certain settings available in Inuktut, with future plans including Inuktut translations. In March, NTI committed $5.4 million to the Pirurvik Centre in Iqaluit, which provides Inuktut-training courses. The money will allow the centre to develop new training programs with the goal of increasing the numbers of Inuktut-speaking professionals and Inuktut language instructors across the territory.

The similarities between Inuit Nunangat and Greenland make them easy to compare, but subtle differences in the historical timeline have resulted in drastically different linguistic landscapes. Establishing a standard orthography is one way Inuit in Canada are following Greenland’s example and Inuktut musical acts, such as The Jerry Cans and Northern Haze, are continuing to make great strides toward promoting the language. But in many ways that’s where the comparisons must end.

The fight for language rights in Inuit Nunangat is unique and can’t be achieved by simply following in Greenland’s footsteps. Inuit in Canada have worked hard to lay the groundwork on their own path towards language survival. Decades worth of investigations, studies and reports have all been completed and now it’s mostly a matter of implementing the plan.

In February, former languages commissioner Sandra Inutiq wrote an essay titled, “Dear Qallunaat (white people),” that pointed out the ongoing systemic racism contributing to the colossal gap between Inuit and non-Inuit in Nunavut.

Article 23 of the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement stipulates that 85 per cent of the workforce should be Inuit, but the number currently sits at 50 per cent. That means half of all government workers (municipal, territorial and federal) are from somewhere else. That rate has an enormous financial implication. Between 2017 and 2023, Inuit will miss out on an estimated $1.2 billion in salaries and benefits, according to a 2017 report titled, The Cost of Not Successfully Implementing Article 23.

“There has been nothing done to reform the system in any large scale and consistent manner, including finally focusing on Inuit employment, education, housing and poverty-related issues (and these are all interconnected),” Inutiq wrote in her essay, which was published on the CBC website. “Imagine, after Nunavut was created, if there was a program to train Inuit to become Inuktut teachers in a deliberate, systematic way? Our language would be thriving rather than on a downward spiral, treated as an inferior language and not worth saving.”

Inuktut is at the heart of the interconnectivity Inutiq writes about. Without it, inequality will only continue.

Adequate, longterm funding is key to supporting the programming needed to ensure Inuktut takes its place as the working language of Inuit Nunangat. Without it, the inevitable disappearance of Inuktut would be a loss for the wider, circumpolar Inuit community and the world.

“I think the richness and understanding of the world and our world in Nunavut and our environment in Nunavut would be lost,” Kotierk said.

“I think that richness would not be lost only to Inuit, I think it would be a loss for this world and the global community.”