Mamta

Reproductive and sexual health struggles for women in India

By Shalu Mehta

This story will take you on a journey to a few different places in the state of Gujarat in India. While reproductive health care for women is an issue of concern across the country, the extent of the challenges can vary based on where the women live. The government of India has created a blanket health policy to address women’s health, but its impact also changes depending on geographic areas.

The Gujarat state can be viewed as a small slice of India, with a mix of people that largely reflects the rest of the country. A bulk of those living in Gujarat are vegetarian, which contributes to malnutrition and anemia rates. Parts of the state are made up of dry farmland, others of urban jungles and some of muddy, mountainous areas.

In this story, you will travel to three distinct places – rural, urban and tribal – in the state of Gujarat to see just how different health care is.

Many of the problems affecting women occur in rural areas and the first place you’ll visit – the Devbhumi-Dwarka district – is one of those areas. It is one of the farthest-west districts in the state. It sits along the Gulf of Kutch and Arabian Sea and many of the villages closest to the main city of Dwarka are beachside. In this district, you’ll be taken to Dwarka, as well as the village of Shivrajpur and a town called Varvala.

Next you’ll visit the urban cities of Ahmedabad and Vadodara, where the health care picture is drastically different. The crowds in these cities are so dense that it’s hard to walk down the street without rubbing shoulders with others. There are hundreds of hospitals here, as well as several domestic NGOs here that work to help women with their rights, including health care.

Finally, you’ll visit the mountainous, lush jungle of the Tapi district on the eastern Gujarat border where you’ll look into the Tribal village of Raniamba and the women that live there.

While all three places will show some similarities – in the way women shy away from the topic of health care because of cultural taboos, for example – it’s crucial to note that the differences between the three are important. They are representative of the struggles many women across India face when it comes to health care access. They also highlight challenges the government grapples with in creating a health policy that can benefit the greatest number of people.

Once a month, a one-room pre-school in the beachside village of Shivrajpur, Gujarat, converts into a pop-up health centre and fills with expecting and new mothers who wait patiently for their checkups. The village juts up against the Arabian Sea and is near the holy city of Dwarka where it is said Lord Krishna built his kingdom. Palm trees offering green coconuts and farmland with sprouting stalks of corn make their way to the sea as herds of cows and camels meander down streets, in between village houses and past the front gate of the schoolhouse.

About a dozen pairs of sandals are neatly placed in two rows on the front porch of the school to keep sand and dust from tracking onto the impeccable tiled floors. A small kitchen inside emits an aroma of Indian cooking—turmeric, cumin, chilli, roti, tomatoes and hot peppers—which will be served to the female health worker and the teacher who presides over the anganwadi.

The female health worker is given that title by her employer, the government of India. It’s her job to visit a handful of rural areas near her home and seek out women who are of reproductive age, usually around the age of 19 and up. She gives them basic health care and teaches them about everything from proper hygiene to family planning.

The anganwadi is like a pre-school where children in low-income areas can learn basics like their ABCs and numbers. It also doubles as a convenient child-care centre for busy parents to take advantage of during the day.

Sitting on the cool tile next to the kitchen in the anganwadi are women dressed in brightly coloured saris and Punjabi suits. Some hold on to their babies while others hold their bellies. They are waiting for their monthly checkup. It’s all part of Mamta Day, a program created by the Indian government to help new and expecting mothers with their health. The word mamta means motherly love – an apt title for a program dedicated to mothers and babies.

In the middle of the group of women is Suna Chamadiya. In English, her sari would be described as bright pink but in Hindi, the word for it would be gulabi, meaning the colour of roses. She is 22 years old and watches nervously as the female health worker prepares vitamin B injections for the women.

Women gather around the female health worker, Sonal Jotnigiya, to get their monthly checkup in Shivrajpur, Gujarat. | Shalu Mehta

Sonal Jotnigiya takes Suna Chamadiya’s blood pressure at the Mamta Day in Shivrajpur, Gujarat. | Shalu Mehta

Chamadiya is eight months pregnant but has ridden her brother’s scooter over nearly five kilometres of rugged, bumpy roads to attend the Mamta Day, despite the risk the journey poses to her and her baby. If she doesn’t make the effort to come to this day, she may not receive any health care or medical advice at all. In the last stage of her pregnancy, that lack could jeopardize the health of both Chamadiya and her unborn baby. There are no doctors or health care workers in her tiny village.

This is her second pregnancy. Her first one ended in an abortion at three months. According to Chamadiya, the doctor said the fetus was deformed and would not survive much past birth. Chamadiya’s in-laws blamed her for the baby’s “deformity” and the need for an abortion, which according to Chamdiya, cost them money.

One day, her husband dropped her off at her parents’ home and never came back. He said he would work in the fields for the day and pick her up after but never did.

A few weeks later, Chamadiya discovered she was pregnant again. When she heard the news, she tried to convince her husband to come back for her and their unborn baby. Chamadiya called him multiple times but his parents told him not to go back for her. Chamadiya says his parents thought she would be too expensive for them to care for.

That was when she was about two months pregnant. Abandoned by her husband, she now lives at home again, depending on her parents, brothers and their wives.

Even at eight months pregnant, she is forced to tend to her family’s home and farm. Taking care of the land is a collective effort and everyone living there has to pitch in.

Chamadiya’s story is not unusual. Many women in India have trouble accessing adequate health care and education that is focused specifically on them and their reproductive and sexual health. In a country that is quickly advancing economically, with resources and attention going towards improving infrastructure, it’s as if the medical needs of women have been overlooked. And it means they are paying the price, from contracting sexually transmitted infections to undergoing unwanted pregnancies to reproductive complications that can lead to disability or even death.

In India, the infant mortality rate is decreasing, but is still higher than the world average at 35 deaths per one thousand births. According to the World Bank the world average in 2016 was 30 per one thousand births.

Due to its population, the HIV/AIDS epidemic in India is the third-largest in the world with an estimated 2.1 million Indians living with HIV. A study conducted by the government of India also found that six per cent of the adult population has one or more sexually transmitted infections. That means about 30 to 35 million people in India contract sexually transmitted infections in one year. The study also found that many of the infections are contracted by young adults who may not be aware that they are infected, which can lead to reproductive health problems later on.

However, based on numbers, Gujarat appears to be doing better than the much of the country, with lower than or at-average rates for infant and maternal mortality and STIs. It does, however, have a slightly higher HIV/AIDS rate compared to the national average.

Gujarat can be looked to as a state where some situations for women are improving, especially when it comes to their reproductive health. But sexual health education is still not prevalent in schools and was actually banned from the public curriculum in six states, including Gujarat, in 2007. Some institutions in other states teach sexual health in upper-level grades but many students, especially women, drop out before then or feel embarrassed or uncomfortable speaking about it, according to studies conducted by the government. For the most part, women are taught about sexual health by their female relatives around the time of marriage when they’re 19 or 20 years old. But they can only rely on limited amounts of information due to a generational lack of education and cultural taboos associated with sex. This leads to less knowledge about adequate protection from sexually transmitted infections or HIV/AIDS, family planning methods, personal hygiene and nutrition.

In February, 2018, India committed to providing free health insurance to everyone in the country in order to make access to care easier. It has not come into effect yet, but it is estimated the program will cost the Indian government close to 991 billion Canadian dollars. But this free health care would only cover government institutions, which don’t always have enough doctors or specialists.

For many women, access to even basic knowledge, such as how to be hygienic while menstruating or what kind of nutrients they need when pregnant, isn’t readily available so they are forced to make great efforts to find it on their own. However, since some women don’t know the benefits to accessing that knowledge, they may ignore it at their own peril.

The new health policy

The government of India released a new National Health Policy in March of 2017. It was the first update in 14 years, and it was based on a government assessment of how effectively the previous policy had addressed a number of concerns. According to that analysis, a number of concerns — such as malnutrition and adolescent deaths – had improved. But when it came to assessing policies affecting the reproductive and sexual health of women, there was no clear picture. That’s because India does not focus specifically on women’s health – and the 2017 policy update did nothing to change that.

Issues that affect women’s health such as HIV/AIDS, access to health care and family planning are addressed throughout the new policy but the actual section titled Women’s Health and Gender Mainstreaming is short and says that a package of services covered in previous paragraphs in the report will be put towards women’s health. It doesn’t specify what those services are. The approach to women’s health is a patchwork, made of bits and pieces from different parts of the policy.

Aspects of women and children’s wellbeing – including their health – is also addressed by the Ministry of Women and Child Development. Even so, most of the resources are invested in children, who are regarded as being most crucial to the country’s future. In fact, the 2017 national budget allotted more funding – about two trillion rupees (38 billion Canadian dollars) more – towards children’s welfare compared to women’s.

In 2016 – about one year before the new National Health Policy came out – the Ministry of Women and Child Development released a draft policy of its own, and called it a “vision for the empowerment of women.” While the policy noted that the Constitution of India has a mandate for the equality and rights of women and that the discourse on women’s empowerment has evolved for the better in terms of legal policies, it also made a point to show that “a lot still needs to be done” to give women equal access to basic rights.

One of those rights is health care, which is highlighted as a priority area in the Ministry of Women and Child Development policy. It suggests focusing on issues such as reducing maternal mortality, focusing on women’s reproductive rights, family planning, and adolescent sexual and reproductive needs – among other things.

Some of the fixes to these issues flagged by the Ministry of Women and Child Development were already being dealt with in the National Health Policy under a program called the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM), which began in 2007. After the program was introduced, there was an increase in the number of health care centres and health workers in rural areas that were operating under the NRHM program. A free ambulance service for rural communities was also established so people could have better access to emergency services. This ambulance could benefit women who need to travel to a hospital in order to give birth.

The rural program also inspired the creation of what are called ASHA (accredited social health activists) workers. In Hindi, the name Asha means hope or desire but in this case, it’s used as a title for government health activists. It’s their job to visit rural areas and educate people – most often women – about proper health care, including aspects of reproductive health care, hygiene, post-partum routines and basic infant care. Even so, the 2017 health policy noted that progress was slow when it came to HIV/AIDS prevention and care, infant and maternal mortality rates and population control – all issues that greatly affect a woman’s health and livelihood.

Many sexual and reproductive health complications can be avoided with proper education about things such as family planning methods, safe sex, hygiene and pre- and post-natal care. Some of these subjects can be taught to individuals when they are young, but studies have shown that both adolescents and adults aren’t getting the education they need.

A 2015 study done by the Indian Journal of Psychiatry found that the sexual reproductive health needs of adolescents in India are being overlooked or not understood by the country-wide health care system.

The study says that many legislators in states such as Gujarat argue that sexual health education “corrupts the youth and offends ‘Indian values,’ leading to promiscuity, experimentation, and irresponsible sexual behaviour.” Sexual health education has therefore been banned in public schools in Gujarat and five other states. The impact of this is enormous.

Since sexual health is not openly discussed due to cultural norms, the study says that the sexual histories of adolescents aren’t always recorded by their doctors. It also notes that sexual health education could help prevent or decrease rates of sexual abuse, pregnancy complications, unsafe abortions and HIV/AIDS.

According to a United Nations AIDS report, there were 2.1 one million adults and children living with HIV in India in 2016. Of those, two million were adults aged 15 and over. Eighty thousand adults and children were newly infected with HIV and 71 thousand of them were over the age of 15.

The most recent National Family Health Survey conducted by the government of India in 2015 and 2016 reports that 10 per cent of women between the ages of 25 and 49 had sex before they were 15 years old. Thirty-eight per cent had sex before the age of 18 and 58 per cent by age 20.

Contraceptive use by married women is just under 50 per cent with the most common form being female sterilization – also known as tubal ligation or in some cases, hysterectomies – followed by male condom use and then oral contraceptives. The numbers in the state of Gujarat vary only slightly from the national averages.

The study showed that most women were going to public health institutions like government hospitals, primary health centres and community health centres to access different methods of birth control. Oral contraceptives, however, were more often acquired from private doctors, not funded by the government.

Half of the women who underwent sterilization procedures for family planning had the operation by age 26. Sterilization is permanent. The women who are sterilized are unable to get pregnant again.

The Indian Journal of Psychology study included findings from an NGO in New Delhi called TARSHI – talking about reproductive and sexual health issues. The NGO monitored a helpline it runs to give people sexual health information and found that it received more than 60 thousand calls from people “seeking information about sexual anatomy and physiology, counseling and referrals regarding sexuality and reproductive health issues.” Seventy per cent of those callers were below the age of 30.

The study found that even in states where sexual health education was part of the curriculum, it was failing to fully address main health issues that adolescents may face including early pregnancies, not waiting long enough between pregnancies, unsafe abortions, sexually transmitted infections, HIV/AIDS and sexual violence.

When it comes to health education for adolescents, the new National Health Policy says it recommends expanding adolescent and sexual health education. One method of doing so is by investing in school health and adding health education to the curriculum to promote hygiene and safe health practices. It also makes note of using schools as primary health care sites.

But in states like Gujarat, or the five others where sexual health education is banned in the education system, expanding the scope of it won’t be possible in schools.

When asked about the health policy, government officials in various offices did not respond to e-mail requests for interviews or said they could not comment.

Rural Gujarat

At the anganwadi, Chamadiya prepares herself for a Vitamin B injection. She waits in line and watches the woman in front of her, biting her nails. The young woman sits in a chair at the anganwadi teacher’s desk. She looks away from the syringe and squeezes her eyes shut as the needle breaks skin on her left arm. It’s Chamadiya’s turn next and she smiles nervously as she inches towards the chair.

Sonal Jotnigiya is administering the injections and performing the check-ups on the women. She is a government employee and her title is female health worker. She arrived at the anganwadi around 11 a.m. with a cooler stocked with injections, vials for collecting blood and medicine like iron pills to offer women at the Mamta Day. This anganwadi is just one of the many places she’ll be stopping at during the week.

Jotnigiya is based at a primary health centre in a nearby town called Varvala. The primary health centre serves as a small clinic where doctors perform check-ups for people living in nearby communities. The anganwadi in Shivrajpur – the village Chamadiya is from – is called a sub-centre. It’s like an off-shoot of the primary health centre where limited services, like the Mamta Day, are offered at certain times of the month.

The sub-centres make it easier for people living in rural communities to access health care. Chamadiya already has to travel five kilometres to get to the anganwadi. The primary health centre would be another seven kilometre trek for her, something she may not be willing to do often.

The medical officer’s office at the primary health centre in Varvala, Gujarat. | Shalu Mehta

An ambulance waits outside of the primary health centre in Varvala, Gujarat. | Shalu Mehta

Jotnigiya lives in a small compound on the primary health centre grounds with her husband. Before she leaves the centre for the day, she meticulously counts all of her supplies and checks in with her supervisor – usually an on-duty doctor – before she leaves. She normally catches a ride to whatever sub-centre she’s headed to with her husband before he heads off to work.

At the anganwadi in Shivrajpur, she quickly sets up her station at the teacher’s desk. She pulls out a blood pressure monitor, iron pills and two scales – one to weigh babies and another to weigh their mothers.

Each woman arrives with a colourful booklet that Jotnigiya can fill in with the latest information from their checkup. She records their weight, blood pressure and notes the medications and injections they are receiving.

Sonal Jotnigiya gives a woman a vitamin B injection at the anganwadi in Shivrajpur. | Shalu Mehta

Sonal Jotnigiya, a female health worker from Varvala, Gujarat. She visits rural communities near her home to deliver primary health care services to pregnant women and new mothers. | Shalu Mehta

Sonal Jotnigiya speaks to a woman at the Mamta Day in Shivrajpur, Gujarat. | Shalu Mehta

“You’re not gaining weight, what are you eating at home?” she asks one of the women as she weighs her.

Sonal says this job is more to her than just a source of income. She works with ASHAs to help women in rural villages near her home and says that having the opportunity to ensure they are happy and healthy mothers is what keeps her going.

“I can help them with their biggest life-changing moment,” says Jotnigiya.

In rural areas like the one Chamadiya is from, the ASHA workers and female health care workers have a large influence over residents who are seeking medical care.

ASHAs provide outreach to rural communities as well as low-income communities in urban centres. They educate residents about health practices such as healthy eating and hygiene but also accompany women who are in labour to government hospitals and help deliver babies.

They find women who might be or are pregnant and bring them to Mamta Days to ensure they receive medical care and also speak with women about family planning methods such as the use of intrauterine devices (IUD), tubal ligation, birth control pills and hysterectomies.

Each ASHA worker in a rural area is assigned one thousand women to look after and is paid 600 rupees (about 12 Canadian dollars) for each baby delivery they direct to a government hospital.

In India, hospitals can be either government-run and funded or private. Having a baby at a government hospital is free and low-income women are offered monetary incentives to give birth in one. It’s the government’s way of discouraging home deliveries. If they decide to go to a private hospital instead, they have to pay around 2,000 rupees (39 Canadian dollars) to give birth.

Without ASHA workers and female health workers, women in rural communities might miss out on crucial information about their own health. ASHA workers educate women about good hygiene practices, family planning, reproductive tract infections, sexually transmitted infections, immunization, birth preparedness, the importance of safe delivery and breast feeding, according to the Ministry of Health website. It is their job to convince women to take their health into their own hands.

On the other hand, ASHA workers receive payment for each woman they speak with that ends up choosing a hospital-based family planning method such as the insertion of an intrauterine device (colloquially called a copper T), tubal ligation or a hysterectomy. This is part of a government plan to reduce population growth and keep women from having babies too frequently.

Jotnigiya says that women are often uneducated about family planning methods. She says many of them avoid the subject completely.

“We recommend things like condoms or IUDs to the women for family planning and they think it’s bad to use them or even talk about them,” says Jotnigiya. “They say their husbands wouldn’t like to use condoms.”

She says there are benefits to teaching women about family planning because many of them will have a baby and get pregnant again as soon as possible. But she says the ASHA workers can have their own motivations.

“Sometimes ASHA workers will only get paid if they take a woman for sterilization or a copper T so they will tell people they need it even if they don’t.”

Jotnigiya started off as an ASHA worker and then trained for two-and-a-half years to become a female health worker. This means she is able to give injections and medicine and draw blood. It also means she has a fixed income, rather than one based on how many babies she helps deliver in government hospitals.

She says having a fixed salary takes her focus away from trying to convince as many women as possible to take up family planning methods or deliver in government hospitals and instead, allows her to ensure they receive the best care they can afford – even if that means going to a private hospital two hours away.

A private hospital is beyond Chamadiya’s means but she says she is diligent about making it to Mamta Days for checkups. She hopes that if her baby comes out healthy, her husband will come back for her.

She has developed a relationship with Jotnigiya who visits Chamadiya at home too.

When asked if she discussed her sexual health with her mother or sisters-in-law, she shrugs and reverts into herself, curling her shoulders in towards her stomach and smiling shyly.

“We don’t talk about those kinds of things,” Chamadiya says.

“If I have questions, I ask the health worker.”

The rural city of Dwarka

Dwarka is the nearest city to Chamadiya’s village and is a well-known tourist and pilgrimage destination. It is known for its ancient Dwarkadeesh Temple, where it is said one of the Indian Gods, Lord Krishna, ruled. Within the Dwarkadeesh gates, line-ups of devout visitors fill the temple grounds. Outside the gates are lines of beggars, some missing limbs and others with children, waiting for alms from temple-goers.

Many visit Dwarka to pray and bathe in holy waters of the rivers that empty out into the sea. In the morning and evening, sounds of drums, bells and prayers permeate the streets as the many temples in the city hold service for locals and visitors.

As the sun sets over the water, single lights begin to switch on along the horizon. They come from fishing boats preparing to float in place for the night.

The main industries for the area are farming, fishing and tourism, although there is an industry for pearl harvesting along the shores of Dwarka as well.

The city has all of the trappings of a tourist destination, with money going towards beautifying and maintaining the temples, beaches and walks along the sea.

There is only one hospital, two gynaecologists, and no paediatricians in the entire city. There are three primary health care centres, one of them serving as Jotnigiya’s base, and 25 sub-centres like the anganwadi that Chamadiya goes to for Mamta Day each month.

Compared to other large cities in Gujarat, Dwarka has a much smaller population of almost 39 thousand according to the 2011 census.

Dwarka lacks the hustle of a large, urban city. Instead, people laze about their days as they combat the heat and humidity that comes from the sea.

Nakhu Nayani, Chamadiya’s mom, sits on the garage floor at her home in Shivrajpur, Gujarat. | Shalu Mehta

There are 45 villages surrounding Dwarka, with Chamadiya’s Shivrajpur being one of them. The rural population outside Dwarka is a little over 51 thousand people.

The total literacy rate for the area is about 58 per cent, which is significantly lower than the national literacy rate of 74 per cent.

In Dwarka, about 60 per cent of the males are literate compared to approximately 41 per cent of females.

Illiteracy can make life especially difficult for women; it can contribute to their inability to take power over their own health. If they are given health pamphlets with extensive writing on them, many will struggle to read and fully understand what they say.

In rural areas like this, being pulled out of school early to help out with work at home or on a farm is common.

Chamadiya’s brothers and father work in the fields while the women in her household tend to the family farm, livestock and homestead. Chamadiya spends her days cleaning and cooking alongside her mother, a younger sister and two sisters-in-law but said she sometimes ends up doing more of the work, despite being eight months pregnant.

“That’s just how it is,” Chamadiya says as she takes a seat on the ground.

Meals must be cooked for the men before they head out for the day and hot chai should be at the ready for the family in the mornings and whenever they take their tea breaks. The grounds must be kept tidy as well.

“There is always something to do,” says Chamadiya.

She left school in grade seven and quickly learned the responsibilities that were waiting for her on the farm and at home. At the age of 20, Chamadiya got married and moved to a nearby village to live with her husband and in-laws.

Chamadiya’s mother, Nakhu Nayani, says she is worried about what will happen to her daughter now. She is uneducated so getting a job will be difficult and she has no husband to care for her.

“We are trying to call her husband back to her now that she is pregnant again,” says Nayani. She sits on the floor of their garage and leans against the cool wall to stay out of the sun’s rays that are pouring in through the doorway. She sips on a cup of hot, sweetened milk from their cow.

“He just left her here and didn’t come back for her,” says Nayani. “His parents think she will be expensive and a waste of money because they already had to pay for her abortion. They blame her for the baby and think this other one will be a problem too.”

While Chamadiya’s mother speaks about her daughter’s situation, Chamadiya shifts to squat on the ground. She says it is more comfortable for her to sit that way.

At the mention of her husband, she looks down, and lets her mother speak for her.

“What can we do?” says Nayani. “We have to convince him to take her back.”

Chamadiya says she didn’t fully understand what was wrong with the baby that she aborted. She says the doctor told her it was conjoined at the hip – with one upper body and two lower bodies – and that there would be no way to save it. Chamadiya says she and her husband made the choice to abort it together.

Her in-laws, however, blamed the deformity on Chamadiya, according to her mother. Regardless of what the doctor said, they were worried Chamadiya would never give birth to a healthy baby again.

When it came to learning about sexual intercourse and the mechanics of getting pregnant, Chamadiya says her sisters-in-law talked to her about it before she got married. She says it’s how everyone learns about sex.

Bavna Nayani, the anganwadi instructor, in Shivrajpur, Gujarat. | Shalu Mehta

Bavna Nayani is the anganwadi teacher who helps out on Mamta Days in Chamadiya’s village.

Nayani said that more often than not, women know little or nothing about their own sexual health. She says they speak about it in secret with family members who are typically equally uneducated about the subject and only learn what is absolutely necessary to know from their doctors.

“It’s taboo,” says Bavna. “People are shy. Nobody feels comfortable talking about it.”

The sex education solution

Ranjan Gamit is the chief of female health workers in the area. She lives in a single-bedroom compound on the grounds of the primary health centre in Varvala. It is up to her to train all incoming ASHAs and female health workers.

She has been working in this field for about 30 years and was once a female health worker like Jotnigiya.

She says that the state of women’s reproductive health has definitely improved in the time that she has been working but that there is still much to be done. Luckily, she says, the government will be providing more funding to hire more female health workers and ASHAs for the area.

In fact, she will be spending most of the day training new ASHAs to begin work in the new year.

About 100 women fill a room at the primary health centre, eager to learn from Gamit and other health workers like her. They will be taught about everything from the nutritional health of mothers and babies to how to talk to women in rural areas about their health.

The training they receive is supposed to teach them the basic skills necessary for the primary care of women. It also teaches them when they should refer a woman to a female health worker, the primary health centre or a hospital.

Since malnutrition is an issue in lower-income, rural areas, the ASHAs in training learn about signs of anemia in women. They also learn how to properly weigh women and their babies.

When they pass their training and officially become ASHAs they are given their uniform – a bright pink sari or Punjabi suit. They are also equipped with a toolkit that contains things like a scale, thermometer, bandages, sanitary napkins, condoms, iron pills and paracetamol.

However, despite all of the training they go through, Gamit says that many people are still reluctant to take the advice of ASHAs and health workers. She says some communities that are very religious won’t even let her or other health workers speak with them, claiming that they are preaching methods — like family planning — that go against the will of God.

“They’ve yelled at me before, telling me to leave and that they have no use for me,” says Gamit.

But she says that the work they do is absolutely important and that it has helped save the lives of mothers and babies.

“Almost everyone is delivering in the hospitals now,” says Gamit. “That reduces the risk for them a lot.”

Gamit says that the next steps are to increase awareness about family planning methods and the prevention of HIV/AIDS, sexually transmitted infections and reproductive tract infections. To do this, she believes education is the key. She says while it may be too late to change the mentality of older women in the community, it’s not too late to educate children about these issues.

“We focus on children because they are the future,” says Gamit. “If they learn about this now then they will teach their children and so on.”

The process is slow, she admits, but worth it.

The sterilization camp

At the one government hospital in Dwarka, women from nearby villages are led down the sterile, white hallways to the office of Dr. Vipul Chandrana who is a general practitioner.

It’s “camp” day – a government program where groups of women are either sterilized via tubal ligation or hysterectomy or have intrauterine devices inserted.

In India, sterilization is the most-preferred method of birth control, followed by IUDs, condoms and then the hormonal birth control pill.

Chairs lining the hallway outside of Chandrana’s office are filled with women who vary in age. Some look to be as young as 20, while others are well over 40 years old. Most of them are barefoot, having taken off their shoes and sandals before entering the hospital as they were trained to do before entering any respectable place. Their bright saris contrast the stark white walls of the hospital and the murky brown of the chairs.

Nurses, also referred to as “sisters” since many are missionaries, run from one end of the hospital to the other. The space is not very large, but still easy to get lost in.

At the centre of the hospital is a round foyer with a murti — a small statue or shrine — dedicated to Lord Ganesh in the middle. He is the elephant-headed Hindu God who is supposed to be the mover of obstacles — a reminder to those that are religious that there is a God watching over them and giving them strength to overcome their struggles.

Standing guard outside Chandrana’s office was an ASHA worker who did not want to give her name. She brought these women to the hospital and would get paid depending on how many of them underwent a family planning operation. She stood in front of the heavy wooden door separating the doctor from his patients and tried to stop others from entering the office.

From inside, Chandrana summoned one woman at a time to discuss their family planning options.

An older woman nearing 60 years of age, who wanted to remain anonymous, sat nervously in a chair beside him. He looked over her charts, remarking that she had high blood pressure and was not taking the medication necessary to control it. He said her high blood pressure combined with her age made her a poor candidate for tubal ligation or a hysterectomy.

“I don’t know why you need any of this at this point because of your age,” said Chandrana.

“She told me I needed it and brought me here,” said the woman, looking over at the ASHA.

Chandrana said if she really wanted some form of family planning, he’d give her an intrauterine device and then sent her back into the waiting area.

“Right now we don’t have an issue of not getting enough funding,” says Chandrana. “There’s plenty of funding for health care here.”

Chandrana says the issue is how funding is distributed and how aware the public is about the services offered to them.

He argues it’s up to people in rural communities to learn about – and actually take advantage of – the health care that is offered to them.

“If people in rural areas aren’t educated about it, then they won’t know what we’re offering them at the hospital in the city,” says Chandrana.

Dr. Vipula Chandrana, a general practitioner who works at the government hospital in Dwarka, Gujarat. | Shalu Mehta

Speaking from his own experiences, Chandrana says he sees a high rate of HIV/AIDS among men as well as sexually transmitted infections and reproductive tract infections among women. He also says that he assumes many women have HIV/AIDS but are not willing to speak about their sexual health with doctors due to the taboo associated with it. But these are his own observations, since he says the local government does not keep track of those numbers.

“It is hard to really tell, “ says Chandrana. “Since many ladies don’t talk about it.”

He says that many infections and illnesses women face are also due to high rates of malnutrition and anemia. He says it is up to ASHAs and female health workers to communicate the importance of being healthy and taking iron pills.

Chandrana says that despite efforts from health centres to provide services to rural communities, if the public isn’t educated about why they should talk about their sexual and reproductive health, they won’t take advantage of them.

But cultural barriers and illiteracy rates means it can be difficult for rural women to learn how to take charge of their own health.

The role of NGOs

About an eight-hour drive away from the salty Arabian sea and the sandy shores of the holy city Dwarka is the larger city of Ahmedabad.

With a population of a little more than five and a half million people, the city and its streets are filled to the brim. Scooters weave in between rickshaws and cars that are often halted on roads as cows amble across. It’s not a tourist destination, but it is a centre of business and education.

Centrally located in the city is a non-profit organization called the Centre for Health, Education, Training and Nutritional Awareness, or CHETNA. The organization aims to approach women’s health from the perspective of women’s rights. It delivers easy-to-understand educational materials to communities where women may not be well-educated, such as rural villages and urban slums.

The organization helps support government initiatives like the National Rural Health Mission but still works autonomously and on its own missions as well.

The CHETNA offices are located on the fourth floor of a cement building that is nestled amongst other shops and behind food carts on the street. The offices are open concept, with a main glassed off workspace and a boardroom that doubles as a library for meetings.

The office’s walls are covered in educational materials that outreach workers bring to different communities, as well as posters and awards demonstrating some of the organization’s achievements.

Swati Mehta is a communications officer at CHETNA and started at the organization doing field work. While she still goes out to communities now, she is more involved in planning, training and communications for the organization.

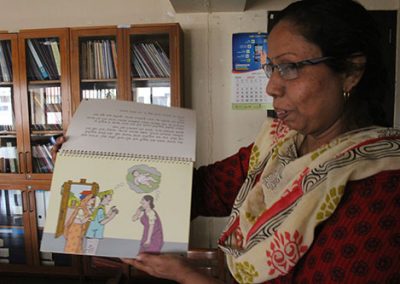

Swati Mehta of CHETNA in Ahmedabad holds up a booklet that is circulated to women in rural and urban low income areas. | Shalu Mehta

Swati Mehta of CHETNA points out a mission statement and other materials used to train employees. | Shalu Mehta

One of her major points of focus is that sexual health should be taught to both males and females so that when they enter into relationships together, they both understand each other.

“What good is it if a woman’s partner does not know what is going on with her?” says Mehta.

The centre makes aprons that volunteers and educators can wear to the communities they visit. Mehta puts on the pink girl’s apron and demonstrates how she would teach children with it.

On the apron, near the stomach area, are a series of flaps with diagrams explaining the female reproductive system. Mehta flips through them, pointing out the images as if she were teaching a group of children. The aprons are meant to be a fun and discreet way for adolescents to learn about their bodies and not feel embarrassed about it.

“In many areas — especially in small villages with lower education — learning about this or talking about it is taboo,” says Mehta. “It’s considered bad or improper.”

Mehta also says that education about nutrition and hygiene, especially for women who are pregnant or of reproductive age, is extremely important.

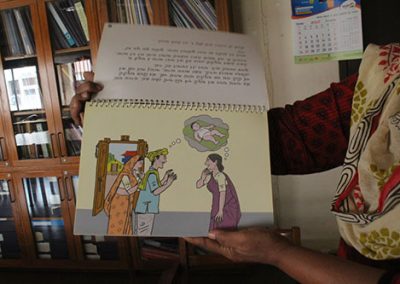

CHETNA produces several picture books that show women the consequences of being anemic or not taking care of their bodies. Since many of the women receiving the books are illiterate, the pictures help them understand the information.

Mehta holds up a holographic poster with a picture of a woman on it. If the poster is tilted one way, she is frowning and next to a plate with little food on it. If the poster is tilted the other way, she is smiling and next to a plate of nutritious, iron-rich foods.

“This way, they can see the picture and understand they have to eat healthy,” says Mehta, putting the poster down.

Mehta says in her experience, children were usually timid when first approaching the sexual health-related materials. She said many girls worried that other community members would see them reading or looking at the pamphlets, books or apron and would worry about what people would think. She said the boys would have a much easier time doing so, because the idea that sexuality is taboo is typically only associated with females.

Mehta says she believes if women are not knowledgeable about their own bodies and their own well-being, it disrupts their livelihood and holds them back from being more empowered in their communities.

“If they can’t take care of themselves, how are they supposed to care for others?” says Mehta. “They need to put themselves first sometimes.”

However, the urban communities CHETNA works in differ from rural ones because they are much closer to medical care centres says Mehta. While Dwarka has only two gynaecologists, the city of Ahmedabad has plenty in both government and private hospitals. That means there are options for emergency cases as well as day-to-day needs.

In Chamadiya’s case, she’d have to travel two hours to a nearby city to get to a gynaecologist if the ones in Dwarka weren’t available.

Mehta says access to proper health care is a bigger problem for women in rural areas for this reason. There just aren’t many doctors out there.

Urban health

In the city of Vadodara, there are hundreds of hospitals serving a population of about two million people.

The streets of Vadodara buzz with the bustle of people who are busy at work, trying to get through their daily grind without being sidetracked by the many vendors and beggars who line the roads. Vadodara is an expanding city, with new developments encroaching into the farming towns and communities around it.

Construction workers and their families are mobile, moving from building site to building site and setting up tent cities near masses of cement that are waiting to be turned into high-rise apartments.

Cows still roam here the same way they do in Dwarka, but instead of grazing on grass they are grazing on garbage and litter that turn the sides of roadways into colourful mosaics of plastic and paper.

Side streets and alleys take residents away from the business of the main roads and shelter them and their homes from the noise that persists through all hours of the day.

In some areas, the homes are large and gated with multiple bedrooms and storeys. Middle-class and upper-class residents own these and keep to their gated communities for the most part.

Lower-class housing consists of row houses that line narrow, rough, unpaved streets. Only scooters, rickshaws and small carts are able to make their way in between the row houses. In the urban slums, shanties made of wood and tarps with satellite dishes hanging precariously off the sides crowd against each other.

One such low-income neighbourhood, in Vadodara, features many narrow streets lined with row houses.

At the centre of the neighbourhood are two things: a temple and an anganwadi. Like Dwarka, the anganwadi’s primary purpose is to serve as a day-care for children who aren’t in school yet.

There are Mamta Days here too.

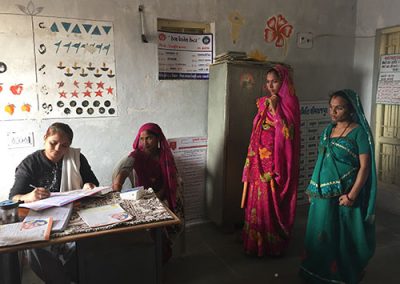

Indira Ashish is an ASHA worker in this area. About a thousand women are assigned to her care. Ashish often makes house calls to pregnant women and new mothers and reminds them about Mamta Days.

“She just had a baby, she just recently became pregnant and she’ll be delivering soon,” says Ashish as she thumbs through a stack of papers on a clipboard, making note of the many women she tends to.

Naina Chauhand and her two-year-old son, Shlok. This is Chauhand’s third child and she had to have a caesarian section to deliver him. | Shalu Mehta

Naina, Hetal, Urmila and Sangeeta Chauhand are among her clients. They are all sisters-in-law, living in row houses that are side-by-side and connected on the terraces.

Hetal just delivered her first child and said the ASHA worker, Ashish, helped her in the months leading up to the birth. She said she received nutritional food packets from the anganwadi that provided her with iron-rich items like lentils and green vegetables. However, Hetal took the lead of her eldest sister-in-law, Naina, and delivered her baby in a private hospital.

“Nobody likes the government hospitals,” says Naina.

Naina has three children – two girls and one boy – who were all delivered in a private hospital. Her baby boy Shlok is the youngest and required a caesarian section when Naina was giving birth to him.

“We have a little bit more money for things like this, and there are so many private hospitals so we could go to the one that worked for us,” says Naina.

Since government hospitals are free, many people believe the quality of care is not as good as what they would get at a private hospital. So even if they cost a little more, people will try to deliver in a private hospital if they can.

Naina says she didn’t go to the Mamta Days because she didn’t know about them during her first two pregnancies.

Urmila and Sangeeta are newly pregnant and make sure to visit the monthly Mamta Days. They say receiving the free food is the best part, but go for the injections and medicine too.

However, they are insistent on delivering in a private hospital as well and have told Ashish that they will not go to a government hospital with her. That also means Ashish will not receive any commission for their deliveries because of this.

Although the Chauhands are from low-income families, living in an urban environment gives them more choice when it comes to doctors. They do what they can to get the best care they can afford and have the liberty to shop around for doctors within their price range at private hospitals. Delivering a baby at a private hospital costs around 2000 rupees – 39 Canadian dollars. If the family is living below the poverty line, they are likely making 100 rupees or less a day.

In communities outside of cities, women suffering from complications with their pregnancies have to worry about private hospital costs as well as travel expenses to a private hospital. And the stigma against government hospitals remains, so most people try go private if they can afford it.

Jotnigiya visits many women in rural communities outside of Dwarka who fear having complications or even having to get caesarian sections. If there aren’t any gynaecologists working at the one government hospital in the city, they have to make the drive to Khumbaliya, a city that is about two and a half hours away. They don’t have a choice.

That was the case with Nathi Vinjooda says Jotnigiya, as she paid her a visit at her home. Vinjooda had a miscarriage at six months pregnant and had to rush to a hospital outside of the city to have the baby and placenta removed. Jotnigiya says Vinjooda was fortunate because her family had some savings they could put towards the procedure in the private hospital.

Jotnigiya says that often, doctors won’t perform a procedure or C-Section in private hospitals without being paid up front. For lower-income families, coming up with money on the spot can become a problem.

Now that Vinjooda has had the baby and placenta removed, Jotnigiya says she hasn’t been able to stop menstruating. She visits Vinjooda often, giving her nutritional advice and ensuring that she is taking iron pills regularly.

The tribal area

Raniamba is a small, tribal village in the Tapi district of Gujarat. It is named after the long Tapi river that winds its way along the Gujarat and Maharashtra state borders.

Tribal areas differ from the rural ones outside of Dwarka because the communities are rooted in tribes that are anthropologically and culturally distinct. They have been around for a long time and have maintained tribal traditions, even alongside modernization.

Gujarat’s tribal belt runs along the eastern border of the state and much of it is located in the Tapi district. There are a total of 29 tribes in the state.

The nearest cities to Raniamba are Songadh and its sister city Vyara. The landscape is mountainous and filled with lush, green jungle. Unlike the dry sands of Dwarka that cover the streets, the ground in the Tapi area is dark brown and moist with water from the Tapi river.

In the entire district, there are 30 primary health centres, 235 sub-centres and five community health centres. Sanctions for more specialist doctors like gynaecologists have also been put in place in hospitals and health centres in Tapi.

A study performed by South Gujarat University shows that the percentage of institutional deliveries by both rural and urban women in the district rose to about 93 per cent in the year 2014. The state percentage of institutional deliveries that year was about 96 per cent.

The same study also shows that child immunization rates are higher in Tapi than in the state of Gujarat. Services like child immunization and hospital accompaniment during birth are offered by female health workers and ASHAs.

Raniamba has a population of about 4800 people. Three ASHA workers tend to the town and four anganwadis hold monthly Mamta Days.

Manju Gamit has been a nurse for 23 years in Raniamba. She says when she first started the job, almost no women wanted to deliver their babies in the hospital. She says it is because traditionally, women had home births with the help of a female family member.

A curtained off area inside the anganwadi where women can lie down and get their blood pressure monitored. | Shalu Mehta

Manju Gamit also says that many women did not know about Mamta Days when they first began so she, alongside other ASHA workers, would go door-to-door to convince women to come.

“They didn’t know what they needed before,” said Manju Gamit as she set up her workstation at the anganwadi for the day. She prepared vaccines and set up a station to weigh babies and check the women’s blood pressure.

Manju Gamit said that many women still don’t come to Mamta Days consistently so she goes door-to-door with other nurses to hand out basic medicine like vitamins and iron pills.

The houses in Raniamba differ from the ones in Shivrajpur. Rather than cement compounds surrounded by vast farmland and sand like Chamadiya’s home, the houses in Raniamba are made out of earthen bricks and wood. They are much closer together, with neighbours’ homes about three metres away from each other and livestock like chicken and cows roaming between yards.

Asha Gamit, an ASHA worker in the area, lives in one of those homes. She has been an ASHA for seven years now and oversees 329 homes.

She says that while she would like to be paid more, or at least receive a minimum salary rather than commission, she enjoys her job a lot.

“I help save some women and their babies,” she says, recounting a story of a woman who had a severe complication.

“She needed an emergency C-section, and the hospital in Songadh did not have a doctor available to operate on her at the time,” says Asha Gamit.

The only other option they had was to travel about an hour and a half to another hospital where the woman might be received. But the woman and her family did not want to go somewhere they were not used to and decided they were going to wait for an opening at the hospital in Songadh.

“I was praying and praying that she would be ok,” says Asha Gamit, almost in tears. “I told her that I would be there and pray for her so we all prayed together.”

Asha Gamit, an ASHA worker in Raniamba says saving lives and caring for women makes her job important. | Shalu Mehta

Asha Gamit says that luckily, a doctor freed up in time to perform the surgery and that the mother and baby were ok in the end.

“Things like this make my job important,” says Asha Gamit.

At the anganwadi, Manju Gamit fills out women’s Mamta Day cards and gives them vaccines while Asha weighs babies in a small scale on the floor. At the back of the school house is a curtained-off area with a bed behind it. Manju Gamit takes women back there, one by one, to check their blood pressure while they are lying down and also draws their blood.

“We got a lot of funding recently to get equipment like this,” says Manju Gamit, pointing at the bed and blood pressure monitor. “We never had anything like this three or four years ago.”

Tribal areas like the one in Tapi are nicknamed “backwards” areas by people not living in them. They are typically lacking in adequate infrastructure like roads and electricity and many of the people living there are low-income. Women living in tribal areas face similar health care issues as those living in rural ones. But the under-developed nature of tribal areas, as well as scrutiny by the World Health Organization in 2013, prompted the government of Gujarat to provide more funding towards the betterment of the Tapi district.

State solutions

Bharat Jalla is an administrator in the government of Gujarat’s health department. He works in Gandhinagar – the state capital – and says that a few years ago, a decision was made by the state and federal governments to improve the quality of life of tribal populations in Tapi.

“It’s a 90 per cent tribal population in Tapi district so there was no development before,” said Jalla.

Gamit says that after the government decided to increase funding to the area, changes came into effect quickly. They were given new equipment to use at Mamta Days and more personnel training as well.

A new state budget was passed on February first of this year, according to Jalla. He says now that the Tapi district seems to have improved greatly, the government will be shifting focus to a new area — Dwarka.

In Dwarka, Sonal Jotnigiya is still visiting homes of women who are struggling to take control of their own health. She brings them booklets to teach them about what they should be doing to stay healthy and teaches them about their own reproductive health and hygiene. Jotnigiya checks up on her patients, making sure they are taking their vitamins and are not over-working themselves, despite the domestic responsibilities that so often get thrown on them even when they are ill or pregnant.

“I work so hard to make sure they get the care they need,” says Jotnigiya. “And there are a lot of problems here like not enough doctors. But what can I do? I work for the government but I feel farthest away from it here.”

Her supervisor, Ranjan Gamit, is optimistic that things will improve soon. She thinks that people’s mentalities are changing and that both men and women are becoming responsible for each other’s health.

“We have spent so much time educating people,” says Gamit. “And now they are getting older and will educate their children and so on.”

But Jotnigiya says she feels overworked trying to educate and care for so many people herself. She sleeps with her cell phone set to loud in case any of the women she oversees has an emergency in the middle of the night.

“I will wake up, take them to the hospital, stay with them all night and then go back to work the next morning. I won’t take a day off,” says Jotnigiya.

Some days, she says she wishes she could take a personal day to recuperate but she knows her job is too important to do so.

“But some doctors will take the day off, and when we have so few that is a problem,” says Jotnigiya.

The increase in funding will go towards improving health programs and increasing health personnel so that people like Jotnigiya don’t feel so overworked. According to budget documents received from Jalla, the state and federal governments have put about 42.7 million rupees (almost 840 thousand Canadian dollars) into various women’s and reproductive health centres and services. However, the task of educating women and children about reproductive health will still largely fall to ASHAs and female health workers due to lack of school attendance and the absence of sexual health education in curricula.

The National Rural Health Mission, which is being continued as part of the National Health Policy, is carried out all over the country, but allocation of funds and policies regarding health care and health education are largely based on decisions made by each individual state.

The World Health Organization defines sexual health as a state of physical, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality and recommends that sexuality and sexual relationships should be approached positively.

Swati Mehta from CHETNA says that sexual health education, especially in rural areas, is hard to monitor. This is because some schools don’t offer it and for those that do, whether or not it actually gets through to children is also difficult to tell since more often than not, students choose not to study it because of cultural taboos.

Mehta insisted that sexual health education for children — especially the basics like anatomy and puberty — is integral to improving their self-empowerment. She says it gives them the ability to take control of their bodies and speak openly about health concerns when entering a sexual relationship with a partner.

Chamadiya’s lack of education and inability to understand her own health and what went wrong with her first pregnancy has affected her life in drastic ways.

Chamadiya says the reason her in-laws and husband abandoned her was because they blamed her for the baby’s deformity, even though the doctor told her otherwise.

Regardless of whether or not Chamadiya agreed with her husband and in-laws, she says she didn’t feel she could reason with them on the subject. Instead, she accepts that the baby’s deformity was her fault and tries to convince them that her soon-to-be-born child will come out healthy.

Chamadiya in Dwarka, and the Chauhands in Vadodara all said they had to rely on limited information from female family members about their sexual health until they met with an ASHA worker when they were pregnant. Just like them, many young women living where sexual health education in schools is banned will have to do the same, waiting until they are married or pregnant to learn about their own health.

The government’s National Health Policy says there will be an emphasis on promoting healthy living but besides using a specific example of teaching yoga in schools, does not elaborate on how this will be done. However, it does mention partnering with NGOs and other organizations to carry out aspects of the policy.

The CHETNA organization is an example of an NGO that works with the government to deliver educational materials to people who need them. But it has limited projects, only working in one or two places at a time.

So while more funding is coming to Dwarka to supply health centres with better equipment and more personnel, it’s still up to women to take their well-being into their own hands. But when they are don’t know why they need to look after themselves in the first place, it is difficult to see how they could be equipped and motivated to care for themselves.

Lack of hygiene, malnutrition and a limited use of protection during sexual intercourse have resulted in numerous health problems for women in India. Sexually transmitted infections, reproductive tract infections and HIV/AIDS, and infant mortality are all consequences of the uneven application of reproductive and sexual health care for women throughout the country. But until fundamental issues such as literacy rates and cultural barriers are addressed in concrete ways, women will not be empowered to take their health into their own hands. And the services that the federal government does fund won’t change women’s health outcomes across the board, no matter how much money is funnelled into them to keep them afloat.

Mamta

Currently, Chamadiya is still living with her parents. Sonal Jotnigiya still works as a female health worker, keeping herself busy caring for women in the many villages surrounding Dwarka. The anganwadi teacher, Bavna Nayani, makes a point to say that she’s still in Shivrajpur running the school, caring for children and helping with Mamta Days.

Nayani is from the same village as Chamadiya and like many other women in her community, only studied until grade seven and then left school to help her family. She says she is the only woman in her family that is unmarried and working but takes great pride in the fact that she is able to care for herself and other women. She says she is happy with the work she does and enjoys helping the women and children that come to the anganwadi.

“[Chamadiya’s] situation is sad,” said Nayani after hearing about Chamadiya’s newborn. “They shouldn’t blame her, but this happens to many women like her.”

On Feb. 5, 2018, Chamadiya gave birth to a baby girl at the government hospital in Dwarka with the help of Jotnigiya. Jotnigiya says she struggled to push the baby out at first. The doctor had to perform an episiotomy — an incision in the vaginal area to enlarge the opening for the baby to pass through — to help Chamadiya during labour. In the end, she delivered a healthy baby girl.

Nayani says Chamadiya told her there weren’t any signs of her husband taking her back, so she’ll continue to live with her parents with their new family member by her side.

Chamadiya now has the option to continue to go Mamta Days up until her daughter turns five to make sure they are both healthy. Her daughter will get standard immunizations and vitamin injections and Chamadiya’s post-natal health, including iron levels and weight, will be monitored. Chamadiya will also be taught basics like how to breastfeed and what to do when her baby is sick.

Despite not having her husband around, Chamadiya is happy with her newborn. With the support of people like Jotnigiya and Nayani, she is not alone. She says she is glad she learned about the Mamta Days and attended them.

In Hindi, the word mamta means motherly love.

The government’s Mamta Days, in combination with the people running them, give women the help they need to deliver babies in a safe environment and feel motherly love for the first time.

But the guidance many women can receive — if they know about it, are offered it and are willing to accept it — can also give them the opportunity to feel love for themselves and understand exactly what their bodies are capable of.

Mamta means motherly love, but it represents the strength of a woman’s love for herself and her children and the positive effects that can come from loving others and loving oneself.