The Bear Dilemma

By Joy SpearChief-Morris

How storytelling impacts bear conservation strategies in the Rocky Mountains

“Grizzly Family.” A grizzly bear sow and two cubs walk in a row. Photo courtesy of Parks Canada.

When Kevin Van Tighem was working at Waterton Lakes National Park in southern Alberta in the 1980s, he spent most of his time as a wildlife biologist being afraid of running into a bear while out on the job.

“I went up a tree one time to get away from the grizzly bear that was probably fleeing from me at the same time! We both reacted the way that we were supposed to react – fear,” Van Tighem, now retired, said in May 2022 while sitting on the deck of his cabin near Pincher Creek, Alta.

Fear – and fear of bears – is what makes us human, Van Tighem said. It makes us smart enough to find solutions to our problems. But this fear has also created a new problem in the hierarchy of nature, where our fear has made us too smart, too powerful.

Technological advances have allowed us to influence nature and have outstripped our natural instincts, changing our relationship balance with bears, Van Tighem said.

“If we then use those solutions out of fear, we become dangerous, and so we are now smart enough to wipe bears off the face of the planet and if we allow ourselves to still think of ourselves as fearful, vulnerable animals, we might very well do that,” he said.

The stories we tell about bears continue to impact how we manage our relationships with them. Bear conservation and management policies within Parks Canada have been evolving over the last 50 years. Central to these changes in policy have been changing ideologies surrounding bears, moving beyond the “fed bear is a dead bear” mentality to a focus on coexistence.

In recent years, the federal government and Parks Canada publicly expressed their commitment to partnering with Indigenous people in conservation efforts, and many parks across Canada have taken steps to incorporate Indigenous people and knowledge into their policies and frameworks.

For Mike Bruised Head, a Blackfoot Elder from the Kainai Blood Tribe, Indigenous knowledge on conservation and the environment is inherent. “Those animals are our way of life through ceremony, through song. All those animals are inside as our spirit,” he said.

Amongst the Indigenous people of southern Alberta, traditional ecological knowledge around grizzly bears is centred on deep respect as well as their cultural and spiritual significance. The value of this knowledge in conservation is just beginning to be understood by western scientists, who are now just starting to lay the groundwork for the inclusion of this knowledge within the parks.

Waterton Lakes National Park at the edge of southwest Alberta has been incorporating Indigenous people and their perspectives and knowledge in a variety of projects throughout the park. Through the inclusion of Indigenous language and cultural awareness from its visitor centre to an all-Indigenous wildlife guardians team, Waterton Lakes has placed itself in a position to potentially be a nation-wide leader in the inclusion of traditional ecological knowledge in wildlife conservation and management.

Bear stories of the West

Our experiences with bears are as individual as the people who encounter them. Throughout the piece, explore the stories of bear encounters experienced by some of the people who contributed to this story.

Kevin’s Story

Kevin Van Tighem is a retired Parks Canada biologist for Waterton Lakes National Park. Photo by Joy SpearChief-Morris.

Waterton Lakes’ Entrance

An undated archival photo of the entrance to Waterton Lakes National Park. Photo courtesy of Library and Archives Canada

Bertha Trail

Looking out over Waterton Lakes from the Bertha Lakes hiking trail. The Kenow Wildfire in 2017 burned over 19,000 hectares of the park, the aftermath of which is still seen today. Photo by Joy SpearChief-Morris.

Horses on the Trail

A man and woman ride on horseback on Bertha Trail in Waterton Lakes National Park in 1952. Photo courtesy of Library and Archives Canada.

Lower Waterton Lake

Where the prairies meet the Rocky Mountains. Lookout onto Lower Waterton Lake. Photo by Joy SpearChief-Morris.

Vimy Peak

View of Vimy Peak and Upper Waterton Lake from townsite. Paahtómahksikimi, the Blackfoot name for Waterton Lakes, means “Inner Sacred Lake.” Photo by Joy SpearChief-Morris.

Paahtómahksikimi Cultural Centre

The Paahtómahksikimi Cultural Centre, named after the Blackfoot name for Waterton Lakes, opened in February 2022. Photo by Joy SpearChief-Morris.

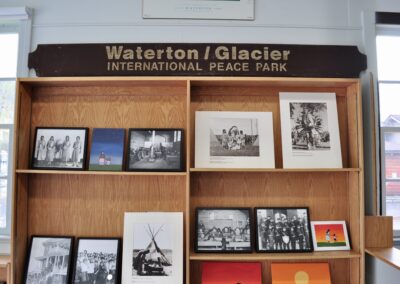

International Peace Park

Waterton Lakes National Park and Glacier Lake National Park across the border are known together as an International Peace Park. The Blackfoot Confederacy also crosses the international border. Photos represent these cross-border relationships in the Paahtómahksikimi Cultural Centre. Photo by Joy SpearChief-Morris.

The bear necessities

Grizzly or black bear? The science of grizzly bears

While many may think they know the difference between a grizzly and a black bear based on colour and size, they might be sorely mistaken. Both grizzly and black bears come in a variety of colours ranging from light brown (or even white like the Kermode bear, known commonly as the “spirit bear”) to blackest black.

What primarily distinguishes grizzly bears is their long claws and shoulder hump for digging in the ground and their dish shaped head and rounded ears. These features have a lot to do with how grizzly bears evolved to survive in their traditional habitat.

“Grizzly bears actually evolved to live in open habitat, not forest. We keep thinking about them being a forested animal, but they’re actually not. They were in the prairies and digging,” said biologist Karine Pigeon, whose research focuses on grizzly bear stewardship and ecology and their relationship to climate change.

There is a general debate amongst experts on whether grizzly bears should be considered a keystone species or an umbrella species. A keystone species defines an entire ecosystem, having a disproportionate effect on helping to determine a healthy landscape. An umbrella species’ impact, on the other hand, is more specific to the other species that are dependent on it. Most agree that as an umbrella species, protecting grizzly bears as the top carnivore on the food chain has a trickle-down effect for all other species in their large habitat ranges.

However, “the world doesn’t fall apart if you take a grizzly bear out of the system,” said Andrea Morehouse, an independent scientist and consultant in the Waterton Biosphere Reserve.

Grizzly bears have a traditional habitat ranging from the coasts of British Columbia to the mountain meadows of British Columbia and Alberta all the way to Manitoba. Over time, grizzlies have been forced into smaller, less favourable habitats within more forested mountain areas because of human action against them.

“It’s not that they were pushed into the mountains. You can look at it that way, or you could also look at it as all of the prairie populations were driven to extirpation, because we over hunted them and killed them all, and the only populations that are left are the ones in the mountains,” said Sarah Elmeligi, a conservation biologist, landscape planner and consultant.

“Grizzly on hind legs.” Photo courtesy of Parks Canada.

Gordon Stenhouse works for Alberta Environment and Parks to collar a grizzly bear while under a tranquilizer. Photo by John Saunders.

It was legal to hunt grizzly bears in Alberta until 2006 when the sport hunting ban came into effect. Then in 2010, a group of activists called the grizzly bear coalition, which included the Endangered Species Conservation Committee, Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, Alberta Wilderness Society and Sierra Club, were successful in getting grizzly bears recognized as threatened species in the Alberta Wildlife Act. Elmeligi, who was part of the coalition, said this is one of the biggest conservation successes of her 15-year career.

“That was a big one, for sure, and that really enabled grizzly bears to have a recovery plan and it’s also very effective in generating public awareness around the status of a species,” Elmeligi said.

Gordon Stenhouse has spent 23 years conducting grizzly bear research in Alberta. He served as a chairman on the Alberta grizzly recovery team that put the first grizzly bear plan into effect in 2008. The plan looked at managing and reducing open road density through bear habitats and raising public awareness on the differences between grizzlies and black bears, the latter of which are still legal to hunt in the province.

The recovery plan is reviewed every five years. The latest recovery plan from 2020 uses the most recent data on grizzly bear population numbers in Alberta from that year. Morehouse and Stenhouse have both done extensive work with the province’s seven bear management areas, or BMAs, which differentiate and group grizzly bears by their genetic sequences based on hair samples. Morehouse said along with genetic makeup, the bears of each BMA are separated by major highways, which serve as impediments to bear movement.

The baseline numbers for the BMAs were established between 2004 and 2008. They were recently all measured or remeasured between 2012 and 2020. The problem with the BMAs, Morehouse said, is that two areas did not have initial measurements done, and different methods were used to measure each of the seven areas. This makes it difficult to determine whether certain areas are having increases in grizzly bear populations and makes it difficult to compare each area with one another over time.

Despite this, the province’s BMAs have shown stable or increasing numbers of grizzly bears. BMA six, known as “Castle,” encompasses the Waterton biosphere and has shown stable and potentially increasing numbers of grizzly bears since 2008.

The first recovery plan in 2008 listed the grizzly bear population across Alberta at less than 700. According to the Alberta Wilderness Association, a 2021 survey counted between 856 and 973 bears in the province.

Sarah’s Story

Sarah Elmeligi is a conservation biologist in Canmore Alta. Photo by Joy SpearChief-Morris.

Gordon’s Story

Gordon Stenhouse is a grizzly bear research scientist at the Foothill Research Institute. Photo by Paul Stenhouse.

Western conceptions and the role of the media

Grizzly bears have large home ranges of over 300 square kilometres, Elmeligi said. And yet, grizzlies are not territorial by nature. Grizzly bears can share overlapping home ranges with other grizzlies and with black bears, which has allowed the two species to coexist as grizzlies were pushed into the forested areas where black bears had traditionally evolved.

“They have their own home ranges. They’ll be territorial on a food resource, but it’s not like a wolf that defends its territory,” Morehouse said. “They overlap in terms of the resources that they’re using, but they do have different niches.”

The assumption that grizzly bears are more dangerous than black bears is also not necessarily true. “Black bears certainly can be very dangerous themselves, but I think people are, in general, more nervous about seeing a grizzly bear than they are a black bear,” Morehouse said.

However, the misconception of grizzly bears as territorial man killers has been a media stereotype since the arrival of settlers in North America. Biologist Kevin Van Tighem credits the beginning of the violent grizzly bear myth to the expeditions of Lewis and Clark in the American northwest.

“They were travelling with muskets, and every bear they saw they shot at, and so they wounded a bunch of bears and, for some reason, those bears then became aggressive,” he said.

“The story of what bears were was actually a story about how we interacted with bears. We made bears dangerous. We made the dangerous story, and then we just kept reinforcing it, because once we were scared of bears, once we saw them as dangerous, potential predators, everybody shot with the first sight and that really started to reduce their population.”

Elmeligi said grizzlies are either portrayed as violent killers or soft cuddly bears from a Disney film. “Every single person, probably, in North America has relationships with grizzly bears, even if they’ve never seen a grizzly bear live,” she said. “There’s all kinds of preconceived notions that we bring forward to how we expect bears to behave on the landscape, and a lot of that does not come from instances of actually seeing grizzly bears on the landscape.”

Elmeligi said that movies, billboards and even newspaper articles promote the storyline of grizzly bears attacking and killing unknowing visitors who walk in the woods. “There’s never a newspaper article of eight people saw a bear in Kananaskis today and nothing happened,” she said.

“Grizzly,” a grizzly on the side of a rocky mountain. Photo courtesy of Parks Canada.

Western media culture has depicted grizzly bears as dangerous and deadly. This stereotyping continues in many aspects of today’s commercial culture, such as these faux bear claws sold at a gift shop in Waterton Lakes National Park. Photo by Joy SpearChief-Morris.

While there is a purpose in warning the public of the dangers of bears, Elmeligi said those stories do not always promote the truth.

“The way more common encounter with bears is person saw bear, bear saw person, bear left, or bear continued about its business, and nothing happened. But that doesn’t really make for good storytelling.”

But beyond this storyline, Elmeligi said bears also symbolize the idea of the untamed wilderness and are a huge draw for tourists in the national and provincial parks. “If I see a bear, it is symbolic that I have experienced or I’ve seen true wilderness,” she said. “We put a ton of assumptions and preconceived notions on these animals that are really just trying to live their life.”

“Really, that bear is just trying to be a bear.”

Traditional Ecological Knowledge and the grizzly bear

Bears have a spiritual and cultural significance in many Indigenous cultures across what is often called Turtle Island. Having lived among bears longer than any settlers on these lands, Indigenous people have their own stories and relationships with them.

The Blackfoot people of the Treaty 7 traditional territory are no different. The Blackfoot Confederacy, consisting of the Kainai, Piikani and Siksika nations as well as the Blackfeet Nation south of the border, are the traditional stewards of the land that today is southwest Alberta.

Mike Bruised Head is a member of the Kainai Blood Tribe, bordering Montana in the south and the Rocky Mountains through Waterton Lakes National Park in the west. An Elder and educator, Bruised Head has a depth of knowledge when it comes to traditional Blackfoot stories, including those of the grizzly bear.

Pa’ksíkoyi is the Blackfoot name for the grizzly bear, a name the grizzly himself told man to call him by. Sometimes translated in English as “greasy mouth,” Bruised Head said Pa’ksíkoyi refers to the layer of moisture and saliva that rests between the grizzly’s lips.

Mike’s Story

Mike Bruised Head is a Blackfoot Elder from the Kainai Blood Tribe and a board member of the Waterton Biosphere Reserve. Photo by Joy SpearChief-Morris.

Bruised Head refers to the grizzly bear as a cultural keystone species, because of its importance to Blackfoot medicine bundles and societies, as well as its cultural significance in many Indigenous nations across Turtle Island.

“When you gather all these different tribes, groups, and you concentrate on the grizzly, there’s just something about the bear, the grizzly bear, there’s something very powerful even though we speak other languages,” Bruised Head said.

“That’s how much we respect, we take that icon, that cultural importance of the bear.”

Evidence of Pa’ksíkoyi having lived as a prairie animal is seen in the Blackfoot names that honour the bear, many of which exist as surnames for many Blackfoot people today, Bruised Head said. He is a descendant of Holy Bear Woman.

Bruised Head said after the signing of Treaty 7 in 1877, the push of settlers into the west by railroad and the forced move of the Blackfoot people to reserves in the 1880s, Blackfoot people were forced to hunt bears to survive. Then as residential schools enforced assimilation into western Christian culture, many forgot the bears’ cultural and spiritual significance.

“The whole thing disrupted our way of life, our freedom,” Bruised Head said.

“The stories that come with the mountains, the bears, clawed animals, the split-hoofed – we were taken out of there and slowly there was a separation, a spiritual separation, where back then we got to see all these animals daily and now we see them in parks, and we’re foreigners to our own mountain lands.”

Today, there are many who practice traditional Blackfoot culture and traditions. For those who respect the grizzly bear, Bruised Head said, Pa’ksíkoyi will appear to them in a dream as a message or a gift. The thunder medicine pipe bundle is still opened after the first thunder in the spring, which honours the original story of the grizzly bear.

Mike Bruised Head looks out onto the Oldman River with his two dogs from his home on the Blood Reserve. Photo by Joy SpearChief-Morris.

Mike Bruised Head tells the story of the grizzly bear

My mother and I drove through the Kainai Blood Reserve on a cloudy May afternoon last spring to meet with Bruised Head at his home. A cattle rancher, his land overlooks the deep coulees and natural prairie grass with the Oldman River just off in the distance.

My mother accompanied me based on a traditional protocol to be a witness to the stories Bruised Head had planned to share with me. My mother is also a fluent Blackfoot speaker and I had hoped she might serve as a necessary interpreter.

Following another protocol, I presented Bruised Head with a gift of sweetgrass and an honorarium, part of a tradition of respect and recognition of the knowledge he as an Elder was sharing with me.

Mike Bruised Head tells traditional grizzly bear story in Blackfoot. Video recorded by Joy SpearChief-Morris. Blackfoot translation courtesy of Wilma Spear Chief.

The healing power of bears

Alongside the Blackfoot people, southern Alberta is also traditionally home to the Tsuut’ina Nation, Stoney Nakoda Nations and Métis settlements. Each have their own cultural connections with the grizzly bear.

Métis herbalist and sash weaver Kalyn Kodiak has learned about the use of local bear medicines from her great-great-grandmother, Marie Rose Delorme Smith. Located in Calgary, her family comes from the Whitehorse Plains in Manitoba and moved to Pincher Creek in the Crowsnest Pass in southern Alberta in the 1880s to start a cattle ranch.

Before learning about bear medicines, Kodiak had dreams about being chased by a grizzly bear, picked up by the scruff and dragged to a lodge of healers. Although she kept trying to run away and hide, the bear always found her and dragged her to where he wanted.

“It was my first dream that really spoke to me, and I think it was a dream about not hiding from what I’m supposed to do and who I’m supposed to be,” Kodiak said.

Kalyn’s Story

Métis herbalist and sash weaver Kalyn Kodiak has a close cultural connection to bears. She uses traditional bear knowledge and medicines in her healing practices. Photo by Joy SpearChief-Morris.

Kodiak shared her knowledge of bear roots, a powerful medicine which shares many commonalities to other bear medicines. “They boost your immune system a lot of time and give you strength. They help to defend you, protect you,” she said.

Brown, oily and fuzzy when fresh with a strong stinky smell that resembles celery, bear root can be chopped up and served as a black tea. Part of the Umbellifer family of plants, bear root can be distinguished on the surface by their upside down umbrella shape with clusters of white flowers. They are commonly found along lakes and streams.

Kodiak said bear medicine is an emotional medicine. Like bears themselves, bear medicines such as dandelion, carrot and burdock offer not only spiritual protection but also physical protection against disease and viruses. They can even help cleanse the body of certain poisons.

Kodiak said the Métis learned about these medicines by watching bears (they do not distinguish between black bears and grizzly bears in their stories), what they ate and didn’t eat, and even how they used certain herbs on themselves. Along with medicine and healing, Kodiak said the Métis learned how to raise their families as attentive parents from bears.

“Family and community are huge values for the Métis and the bears. The bears taught us how to be good family members to each other,” she said.

Kodiak said bears are associated with not just healing but also courage and protection. Those who are recognized for sharing these bear traits would often hold the role of protectors within the community.

“They can also be really fierce warriors, if that’s what they choose to do, and if they feel like they’re called to do,” she said, adding those with bear traits are often water protectors as well as protectors of cultural knowledge.

However, this respect for bears did not mean the Métis avoided hunting them. Bears that were hunted for food were not necessarily sacred, Kodiak said. Bear hunts were a common practice for the Métis and all of the bear would be used, from the meat and fat to the hide and claws for cultural and medicinal purposes.

“Depending on your Métis community, you might pray to the bear for healing, or for strength or courage,” Kodiak said of bear hunts. “I know that men sometimes ate bear meats for strength and for virility as well.”

While her own closeness to bears means Kodiak would not eat bear meat, she has facilitated a biannual bear harvest in Calgary since 2019 with the help of a Métis Elder Wil Campbell and Cree knowledge holder Shane Maurice using bears that have died through various accidents in the parks. She’s made sure to involve local youth to make sure these bear teachings continue to be passed onto the next generation.

A collection of medicines provided by Kalyn Kodiak including a jar of bear root, white sage and a bag of tobacco. Photo by Joy SpearChief-Morris.

Parks Canada’s bear management policy – then and now

The ongoing perception of bears as mankillers has had an impact on Parks Canada’s own bear management philosophy and policies. Van Tighem worked with Parks Canada, mainly in Waterton Lakes and Jasper, for about 34 years and retired as a superintendent of Banff National Park in 2011.

Van Tighem said when he started with Parks Canada in the 1970s, grizzly bears were valued higher than black bears. Black bears that might wander into town and cause trouble were often shot on sight. Grizzlies would be given a second chance, but upon that second chance, might still be given a death sentence out of the perception of “human safety.”

“A good bear is a bear that stays out of trouble. A bad bear is a bear that hangs around where people are, usually just because of food, and you got to get rid of the bad bears,” Van Tighem said.

Alex Taylor worked in Parks Canada seasonally for almost 30 years. Starting at the age of 20 killing weeds, he worked his way to the fire department and finally as a human-wildlife conflict specialist throughout Lake Louise, Yoho, Kootenay and Banff, retiring from Parks Canada in 2018. He now works as a conservation and wildlife specialist in his own drone company.

In his time working at Parks Canada, Taylor saw the wildlife management sector evolve from the “problem wildlife” sector to “human wildlife conflict,” and finally to “human wildlife conflict and coexistence” in 2017.

The changing of the name of the department matters, as does the terminology of “problem bear,” said Dan Rafla, a human-wildlife co-existence specialist in Banff National Park.

“At the heart of it though, the words do matter. But at the same time, the intent probably of the last generation or so was people really worked hard because they cared so much about wildlife – people who worked here, whatever their title was – to coexist,” Rafla said.

Alex Taylor, an independent conservation and wildlife specialist, retired as a Human-Wildlife Conflict throughout Lake Louise, Yoho, Kootenay and Banff National Parks in 2018. Photo by Lee Narraway.

In the 1960s and ’70s, tourism in the national parks began to grow more steadily, creating a modern dynamic of people and wildlife having to be managed, as more people fed wildlife and wildlife attacks increased, Taylor said.

In 1978, following in the footsteps of Yellowstone National Park in the United States, Jasper National Park closed its open garbage dump, which had been a huge attraction for wildlife seeking easy meals in town. Many other Canadian parks soon followed their lead.

Van Tighem, who was working as a biologist within the Canadian Wildlife Service in the park at the time, saw a notice in the park warden’s office one day saying any black bears in town were to be killed on sight.

“It was because they closed the dump, and they just assumed all the dump bears are going to go into town and attack the kids,” he said. The directive was met with local complaints and was soon ended, but not before 36 black bears had been killed that year, Van Tighem said. Grizzlies would be trapped and hauled away.

In the following decade, the parks began to use bear-proof garbage bins in Banff, Lake Louise and Waterton to help eliminate the undesirable food source. “That was sort of the start of the evolution of that thinking that it wasn’t always the wildlife that was the problem, that there is a human element to all these issues,” Taylor said.

Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, the next generation of wildlife specialists wanted to change the management of bears and wildlife with a focus on conservation. The main drivers of the bear management policies came from the regional and national offices for Parks Canada, as is done today.

Van Tighem said there were three things that helped change how bears were managed over the course of his career. The first was work done by Parks Canada to get ahead of reducing conflict issues with visitors, such as closing down the garbage dumps.

“Suddenly, you weren’t dealing all the time with garbage habituated, food habituated bears, and it allows you to think about bears differently if you remove that reactive dimension out of management,” he said.

The second was a combination of work done by cinematographer Bill Schmalz and naturalist Charlie Russell.

Schmalz’s 1978 movie, Bears and Man, was commissioned by Parks Canada to educate the public on bears and keep bears from getting into trouble with people and being killed.

As a naturalist who studied grizzly bears, Russell was a defender of the mentality that bears were not unpredictable and only dangerous when people made them so. Known as a man who befriended and even lived with bears, the bulk of his public work and writing appeared in the 1990s and early 2000s.

“He moved away from objectifying bears and more towards subjectifying them. He knew bears as individuals, and he knew bears as equals,” Van Tighem said. He once got Russell to do a workshop in Waterton for staff and the park warden, who did not agree with Russell’s ideology about the relationship between bears and humans.

The last factor, Van Tighem said, was the end of the bear hunt in 2006, which allowed the grizzly population to recover, while removing “a fear factor from the relationship between bears and us.”

“Grizzly bear traversing around the wildlife fence along the Trans-Canada Highway.” Photo courtesy of Parks Canada.

“It was like turning the kaleidoscope, a bunch of things fell into a different perspective, and it started to create this possibility that we could think about bears differently,” he said.

Van Tighem’s own ideology evolved over time. He can now say he likes spending time with bears and is so comfortable he authored the 2013 book Bears Without Fear, which examines humans’ relationships and attitudes towards bears.

“I understand that an encounter with a bear is not intrinsically a dangerous encounter, it’s just an encounter with a bear, which is a gift,” Van Tighem said.

“My relationship with bears has reached the point where I actually prefer their company than the company of humans, to be honest!”

Parks Canada and bears today

Today Banff is home to about 60 grizzly bears, with another 20 or 30 in Yoho, Rafla said. Waterton-Glacier and their surrounding regions are home to about 30 grizzlies.

Human-wildlife coexistence specialists in the different parks work to manage wildlife populations and visitors to “maintain a level of coexistence, keep animals alive and acting appropriately” while also managing humans to “achieve coexistence,” Rafla said. They also work to manage the ecosystems of each park repository.

Taylor said human-wildlife conflict specialists act as park wardens, keeping the peace between wildlife and visitors. They are trained to deal with wildlife emergencies from an animal being hit by a car to an attack.

“The wildlife is constantly coming across people and having to navigate through that, and the dynamic is further complicated by the fact that the people want to see the wildlife and get really excited when they see that,” he said.

“We’re there to sort of keep the peace, try and manage people first, and let the wildlife do things naturally, but it’s not always easy.”

Alex Taylor clears a traffic jam or “bear jam” while working for Parks Canada as a collared grizzly walks across the road in front of him. Photo by Brian Spreadbury.

Rafla said a lot of new information on what bears need has come to light in the last 30 years. Translocating bears, for example, used to be seen as a disaster or a death wish, as it would involve moving a bear into an unfamiliar territory where it would have to fight to survive. However, a 2022 study by Stenhouse involving radio collaring bears showed that in comparison to “resident” bears, translocated bears who were moved to a new BMA showed a 75 per cent success rate.

Previously, wildlife experts assumed translocated bears would become repeat offenders in their new area and be more dangerous, but Stenhouse’s study found that translocated bears were more preoccupied with adapting to their new environment, in fact choosing less favourable habitats than the resident bears.

Dan’s Story

Dan Rafla is the human-wildlife co-existence specialist at Banff National Park. Photo by Brandy Dahrouge.

There are four main steps used in managing bears throughout all of Canada’s national parks. Resource availability might vary between parks, but the philosophy across Parks Canada stays the same, Rafla said.

When a bear exhibits undesirable behaviour, such as wandering into a town, campsite or area where it could prove a danger to humans, the first step a wildlife specialist might take is to use what are called “hazing tools,” to “regain that weariness that bears have maybe towards people.”

Hazing techniques work on a continuum and often require assessing moments of opportunity and specific bears. These techniques could include using vehicle lights, sirens, horns and other noise stimuli, or using a chalk ball or paintball gun to hit or hit around the bear. Determining what tools are needed requires an understanding of each individual bear and what is needed for each situation.

At the high end of the continuum, shotguns using rubber bullets or beanbags could be used as a painful stimulus and a very effective tool when used cautiously. “It doesn’t hurt too much, but it’s something that’s uncomfortable,” Ralfa said.

When hazing does not appear to be working and a bear continues to exhibit the same behaviour, aversive conditioning might be used over time to change an animal’s behaviour. Food conditioned bears require more conditioning than others, Rafla said.

When hazing and aversive conditioning don’t work, the specialists might consider relocations or translocations. Relocations move a bear within its home range, which could still account for over 185 square metres, Rafla said. A translocation physically moves a bear outside of its home range, but it is a tool that still rarely happens.

Terminating a bear, because it serves too great a risk to people’s physical safety, is a last resort and seldom used.

Beyond wildlife management, Rafla said, human wildlife specialists look to address the root causes of conflicts. “It’s about looking at wildlife connectivity, wildlife movement, habitat security within these built-up areas.”

Education serves as a major tool, and wildlife specialists use a lot of tools including social media and the Wildlife Guardians Program to ensure park visitors are educated on bear safety and how to proactively coexist.

“We have the highest standard in which to try to coexist, to make a real effort to keep these animals on the landscape, and that is our expectation, and that is how we’ve managed over the last number of years,” Rafla said.

Carnivores on the prairies

A cow grazes on the foothills of the mountains in June, 2022. Many ranchers in the Waterton biosphere have to manage grizzly bears hunting their cattle. Photo by Joy SpearChief-Morris.

About 50 kilometres east of Waterton Lakes National Park, just south of the Town of Cardston, is the family ranch belonging to Jeff Bectell. His family has ranched this land, raising cattle, for over 100 years since 1917. But what Bectell is most known for in the community is his role in decreasing conflicts between ranchers and grizzly bears.

Bectell is the coordinator of the Carnivores and Communities Program with the Waterton Biosphere Reserve. With financial support from the Alberta provincial government, the program uses a variety of mitigation techniques — electric fences, deadstock boxes, bear-proofing grain bins and public education — to decrease the number conflicts with bears and create a sustainable future for wildlife and for the people whose livelihoods rely on the shared landscape.

Driving around Bectell’s ranch, it’s easy to see why the area is a bear paradise. His ranch lies at the edge of the Rocky Mountains boasting acres of natural grasslands, making a home to a variety of wildlife like sandhill cranes, hawks, hares and deer.

Bectell’s first bear sighting on his ranch was around 1993, when he saw two young grizzlies digging for gophers near a patch of willows. Before that, his family hadn’t had any experience with grizzlies showing up on their land for as long as Bectell can tell through his family history.

“We thought it’s maybe a bad berry year and these two bears just happened to wander down. I didn’t think, ‘Oh, this is dangerous,’ or, ‘These bears are going to kill something,’” he said. “But I also thought it was a one-off. It’s not something that would become commonplace.”

Yet, as more grizzlies started making their way onto other ranchers’ property, more people began to reach out to Bectell with their complaints. Around this time, Bectell had been involved with local community meetings related to seismic activity and oil and gas impacts on landowners, and so he began to hear more about bear problems instead of seismic activity concerns.

Bear management in the province of Alberta.

Outside of Waterton Lakes National Park, bears are managed on both public and private lands by Alberta Fish and Wildlife.

According to John Paczkwoski, the human wildlife coexistence team lead for Alberta Environment and Parks in the Kananaskis region, the current mandate in the province is to “conserve lands and the species that live there.”

Paczkwoski has over 30 years of experience in carnivore research, primarily bears, in Alberta and British Columbia. He said that grizzlies foraying out into ranch lands, their more historical habitat, is a high-risk, high-reward lifestyle for the bears. It also proves to be a “fascinating next question for bear conservation,” as there are no bear management resources in place east of the mountains into the foothills.

“There are unsecured grain bins and there’s calving and there’s all sorts of these food sources, which are just heaven for the bear,” Paczkwoski said.

“But they don’t realize that huge reward and protein, which is the currency of bears, can put them on the wrong side of management and they could get relocated or captured or even killed depending on what they’re doing.”

Alberta Fish and Wildlife will compensate ranchers whose cattle are killed by grizzly bears, black bears, wolves, cougars and eagles. A wildlife officer is able to confirm a grizzly bear killed the livestock using the “banana peel” method a bear uses to eat their prey. A calf considered a “confirmed kill” by a bear will receive full market value, while a “no kill” receives nothing.

When a wildlife officer cannot be 100 per cent sure if a calf was killed by a grizzly bear, it’s called a “probable kill.” In that case, the rancher can receive half the market value of the livestock if another kill by what appears to be the same predator is found within three months and 10 kilometres from the original kill spot.

Bectell said the reality is, it’s sometimes hard to prove a bear killed a cow because of how little of the carcass might be left for the wildlife officer to assess.

Around 1995, Bectell said he experienced his first livestock kill by a grizzly bear. One of his calves received a “probable bear kill” from fish and wildlife, but a week later his neighbour lost a calf to what was considered a “probable wolf kill.” Neither rancher was compensated for their loss.

“There was some frustration in how it went — the compensation investigation — and just the bureaucracy of the program frustrated me a little bit,” Bectell said.

“It’s part of what launched me on to 10 or 15 years of involvement, is just trying to fix these things so they make a little more sense.”

The making of Carnivores and Communities

Jeff’s Story

Jeff Bectell, a rancher and the program coordinator for Carnivores and Communities, stands on his family ranch just outside Cardston, Alta. Bectell’s family have ranched this land since 1917. Photo by Joy SpearChief-Morris.

Around 2007, Bectell became involved in community meetings about how to manage local bear conflicts with ranchers. Many of these meetings featured angry community members and weren’t leading to constructive outcomes.

“We decided if we were going to do a bear meeting it had to have some goal or some positive outcome, and so we worked really hard,” Bectell said. “We got some other ranchers in the area and fish and wildlife officers in the county, and we tried to find out what other people were doing.”

In January 2010 Alberta Fish and Wildlife representatives met with local community members in Cardston to discuss how to better manage grizzly bears in the area. They looked at what the nearby Blackfeet Reservation in Montana and in Twin Butte, Alta. had accomplished, such as creating a steel deadstock box collection process to keep dead livestock (“deadstock”) away from predators.

A week later, Bectell received a call from fish and wildlife. The Alberta government wanted to give their ad-hoc community group $10,000 to mitigate bear conflicts. Around the same time, Bectell was becoming involved with the non-profit Waterton Biosphere Reserve, who offered to pay a rendering company to pick up carcasses from the deadstock boxes.

In 2011, the Waterton Biosphere Reserve was asked by the Alberta government to take over a $240,000 grant that had previously been allotted to the municipalities of Pincher Creek and Cardston, as well as Ranchland and Willow Creek (which do not fall within the Waterton biosphere) to help manage bear conflicts over the course of three years.

“That’s how the Carnivores and Communities program congealed into what it is today,” Bectell said.

As a flagship program for the rest of the province, Carnivores and Communities has been successful in securing provincial funds each year as well as occasionally federal and other grant money.

Through the Carnivores and Communities program, the Waterton Biosphere Reserve provides a cost-share opportunity for ranchers who might need assistance with certain bear mitigation techniques, such as putting up electric fences or steel deadstock boxes.

“Shoot, shovel and shut up”

Bectell feels empathy for ranchers who may wish to take matters into their own hands.

However, it has been illegal to hunt grizzly bears in Alberta since 2006, unless it can be proved the bear was shot in self-defence. Shooting a grizzly bear can land the person responsible a fine of up to $100,000 and a potential appearance before a judge for poaching.

“I think we have a pretty strong enforcement program in Alberta,” Paczkwoski said. “I think it’s pretty easy to get caught with genetics and dash cams and the world watching nowadays.”

But Bectell warns against falling prey to the stereotype that ranchers are playing the “shoot, shovel and shut up” affair when it comes to grizzly bears on their land. “Most ranchers do not hate grizzly bears. They just don’t like them to cause them problems,” he said.

General thinking around grizzly bears is changing in the ranching community, Bectell said. “There was a lot of fear and a lot of anger, where now some people may be more like me and other people might say, you know what, I’m stuck with the bears. I’m not happy about it, but they’re here. This is our reality now.”

Bectell attributes a lot of this changing mentality to the Carnivores and Communities program and fighting to ensure that ranchers are properly compensated for any lost livestock, which he has been lobbying the provincial government to improve.

“If all we do is kill problem bears, that’s not sustainable. If all we do is pay high compensation when your cattle are killed, but we don’t do anything to keep them from getting killed, that’s not sustainable,” he said.

“But when they all work together, we generate fewer problem bears, we have less conflict, we have to kill fewer bears, it’s a positive loop.”

The bear lover

Bectell has become synonymous with Carnivores and Communities, known as the rancher doing his part to save the grizzly bears from becoming the epitome of “fed bear is a dead bear.” Interestingly, Bectell does not see himself as a lover of bears.

“The motivating factor for me getting involved in this was helping the people around me. It was not to help the bears. It was to help the people,” Bectell said.

“I’ve said it at meetings. ‘Just putting it out there everybody. I’m not a bear lover. I’m not a bear hater. I’m just a rancher!”

Back to Waterton Lakes

Connecting Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Alberta

Connecting Indigenous knowledge to conservation efforts has become more important in the public discourse, particularly since the release of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s 94 Calls to Action in 2015 and following the finding of unmarked graves of residential school children in 2021.

Although the Kainai Blood Tribe and Piikani First Nation reserves fall within the same area of southwest Alberta, they are not included within the Waterton biosphere. “It would be inappropriate for us to just say, ‘you’re in the biosphere,’” Jeff Bectell said of their omission.

Bectell said Carnivores and Communities has reached out numerous times to Kainai’s chief and council, but at the time of publication they are not involved with the program. Mike Bruised Head is involved with the Waterton Biosphere Reserve as part of its board of directors, having also served as the chairman of the Kainai Ecosystem Protection Agency, or KEPA.

Bectell said he would be interested in seeing more cooperation between the Blackfoot community and Carnivores and Communities.

“I have done presentations for school groups from the reserve at their invitation about the program, we’ve participated in their KEPA Summit,” he said. “We certainly work together, but it still sort of continues to be two different worlds a bit and I would love to see it be a little more one.”

Across the province of Alberta, John Paczkwoski said the government is moving forward in good faith with Indigenous nations when it comes to matters of conservation. “We’re trying to build these relationships and incorporate traditional knowledge, both supporting morally and through going after grants and financial support and engaging the time.”

In 2016, the Stoney Nakoda Nations in the Kananaskis Valley created a cultural assessment on enhancing and expanding grizzly bear conservation and recovery efforts using traditional ecological knowledge. The assessment involved cultural monitoring in coordination with Alberta Parks and the Foothills Research Institute, interviewing Elders and conducting traditional bear ceremonies.

Currently, Alberta Parks is undertaking the second phase of the cultural assessment with the Stoney Nakoda, which is now federally funded. Phase 2 involves getting a broader perspective of the wildlife corridor, including a new wildlife overpass over the Trans-Canada Highway outside of Canmore.

Paczkwoski, who was involved in the early stages, said the project involves building trust between the Stoney Nakoda and Alberta Parks, as well as an open exchange of information between the two groups.

“I hope this is the beginning of a long-term relationship, and that we continue to build on these and support one another,” he said.

John’s Story

John Paczkwoski is the human-wildlife coexistence team lead for Alberta Environment and Parks. Photo by Joy SpearChief-Morris.

“Trusting anyone — trusting anything — it’s a slow process but building that relationship around the natural world and the land is maybe a good place to start.”

The knowledge weaver

Federally, Parks Canada has stated its commitment to recognizing and honouring “the historic and contemporary contributions of Indigenous peoples, their histories and cultures, as well as the special relationships Indigenous peoples have with ancestral lands, waters and ice.” This, the government says, includes Indigenous traditional ecological knowledge in conservation.

In Waterton Lakes National Park, Carleigh Grier-Stewart is the first person across all of Parks Canada to hold the role of knowledge weaver. Waterton Lakes’s knowledge weaver is the newest position in the park responsible for integrating Indigenous knowledge into western knowledge in resource conservation.

The position is a result of Canada’s Nature Legacy Initiative, announced in 2018 by the federal government to collaborate with Indigenous partners, stakeholders and other levels of government. The program’s aim is to protect and conserve 25 per cent of biodiversity across Canada’s land and oceans by 2025 and 30 per cent by 2030.

In 2021, the government invested an additional $2.3 billion across five years into the initiative. Funding allocated to Parks Canada falls under four pillars of work: Indigenous conservation; ecological integrity, species at risk and climate change; landscape-scale conservation; and knowledge development use and sharing.

Carleigh Grier-Stewart is the first person within Parks Canada to hold the position of Knowledge Weaver. Her job is to incorporate Indigenous knowledge into western resource conservation. Photo by Joy SpearChief-Morris.

A member of the Piikani First Nation, Grier-Stewart took on the role of knowledge weaver in 2021 after working as a wildlife guardian in 2019 and then as a public outreach education officer with the Indigenous liaison officer.

Though the resource conservation team within Waterton, Grier-Stewart works with Elders, Knowledge Keepers and community members from Kainai and Piikani, their county land departments as well as KEPA to build relationships and offer support through the park, such as funding through the Nature Legacy Initiative.

Grier-Stewart said the objective of her position is to eventually have Indigenous knowledge woven into each branch of the park, including conservation policies around bears, but the inclusion of this knowledge is currently minimal.

“Indigenous people have coexisted with bears for many years and Parks Canada has a lot to learn from us, Indigenous people and our culture, and so I think it’s really important that Indigenous perspectives are being included and being brought to the table,” she said.

“It’s really important because this is our territory and our ancestors were able to coexist with bears, so I think it’s really important that we’re able to express that.”

Grier-Stewart said the addition of her role to Waterton has been an eye-opener for a lot of its employees. “I think that it’s impacted in a way that is more respectful in the relationship building process and just being very respectful and making sure that the relationships are meaningful and taking it slow and careful,” she said.

As an Indigenous woman, Grier-Stewart said it feels right to have Indigenous people working in the park and being able to share their perspectives on what goes on within it. “This is where we come from, for Blackfoot people, the Waterton area, or Paahtómahksikimi, is where our creation stories come from.”

“Being able to be here and being able to represent where we come from is really important and I’m really grateful to be here.”

Paahtómahksikimi, the Inner Sacred Lake

Outside of conservation, Marjie Crop Eared Wolf works as a liaison between the Kainai Blood Tribe and Waterton Lakes, in the Paahtómahksikimi Cultural Centre.

Crop Eared Wolf’s position developed through the creation of the new visitor centre for the park which opened in February 2022, after the previous visitor centre was destroyed in the 2017 Kenow Wildfire.

Waterton reached out to the Blackfoot Confederacy to invite them to contribute to the development of exhibits within the visitor centre to acknowledge the park’s presence on traditional Blackfoot territory. Crop Eared Wolf’s position developed out of a need for a liaison who would communicate this cultural knowledge.

“Blood Tribe had a group of Elders and they were sharing knowledge about the place, and the way I understand it is a lot of information was being lost in that translation or that relationship between the two,” Crop Eared Wolf said.

“So, I’d meet with Elders, gather that information and then relay it back to the people that were developing the exhibits and then that way we were able to include our stories.”

Much of the knowledge shared in these discussions resulted in the large array of Blackfoot language, stories and knowledge incorporated into the visitor centre. From the traditional Blackfoot names for plants and animals, trails, mountains and landscapes, to the inclusion of Blackfoot language heard through the speakers as you enter the centre and in the public bathroom.

An important piece of knowledge the Elders shared about Waterton, Crop Eared Wolf said, was its purpose as a place for trade. “All of that information came from the Elders sitting there with the map, they were able to indicate trade routes to different nations, then they actually provided the Blackfoot names that we have for those other nations,” she said.

Waterton was also a place of treaty between the Blackfoot people and the animal world.

An important distinction the Elders had to make was not every mountain or trail had a traditional name amongst the Blackfoot, because “we don’t give names to things that we don’t have a relationship to,” Crop Eared Wolf said.

This became important for the naming of trailheads and various species of the same animal. Crop Eared Wolf said the park would often ask for names of specific trails and animals for which the Blackfoot people didn’t have a specific name for. Some of them did, she said, and some of them didn’t.

Marjie’s Story

Marjie Crop Eared Wolf is the Kainai Blood Tribe Liaison, working in the Paahtómahksikimi Cultural Centre at Waterton Lakes National Park. Photo by Joy SpearChief-Morris.

This cultural awareness about naming became particularly important in the case of the grizzly bear. In the visitor centre, the Blackfoot name for the grizzly bear appears as the commonly used euphemism of pa’ksíkoyi as opposed to the more general kiááyo, for bear.

“We are being culturally aware of ourselves. When you’re culturally aware of your community you take things into account and you do things the right way,” Crop Eared Wolf said.

The spiritual significance of grizzly bears carries a stronger relationship for some Blackfoot people, particularly those who hold medicine pipe bundles in connection to grizzly bears. These members have what Crop Eared Wolf referred to as an “avoidance relationship” with the name “grizzly bear.”

“Because of that avoidance relationship, these people cannot see them, hear them or be spoken to about them, and so we don’t say ‘bear’ we don’t say kiááyo in front of them,” she said. “In a kind of roundabout way to respect them and their avoidance relationship, we use the term pa’ksíkoyi which, as I understand it, translates to ‘slobbering mouth’ or ‘running mouth.’”

From these Elder group discussions, the Blood Tribe were also able to secure a building in the park for the Blackfoot Cultural Centre in 2018, which has developed into the Paahtómahksikimi Cultural Centre. Using the Blackfoot word for Waterton as the name was important for the Elders as well, Crop Eared Wolf said.

“The Elders really push for us to reintroduce the language and the names for these places, because they’re significant and especially this place,” she said.

“Places of significance are recognized as places that are alive. We hold spirit, and so there’s knowledge that comes with that and teachings and just a whole lot of really deep knowledge.”

The Paahtómahksikimi Cultural Centre has helped preserve some of the knowledge that was shared by the Elders that was not able to be incorporated into the visitor centre. Today, they connect visitors with knowledge of the Blackfoot people and their culture as a place for relationship building. They hold powwows, traditional game events, beading and sewing workshops, showcase local artists and other events around traditional names for plants and their uses.

“I feel like there’s not enough education or knowledge being shared within the wider public, that we kind of get stereotyped or typecast and in this space we’re able to share a lot of the culture and knowledge that we have not only as ourselves, but of this area,” Crop Eared Wolf said.

Waterton Lakes’ grizzlies

Waterton Lakes currently has 30 resident grizzly bears. Rob Found, Waterton Lakes’ wildlife ecologist for the last two years, is the lead supervisor for the park’s widllife officers. They are responsible for dealing directly with conflicts with wildlife when they arise, such as a bear wandering into a town or campsite, as well as proactively trying to prevent these conflicts and promote coexistence.

Although the overall management structure for bears within the park is directed by Parks Canada’s national office, Found said on-the-ground strategies come down to experience from officers in individual parks and communication between them.

Two grizzly bears graze in a grassy field. Photo courtesy of Parks Canada.

“Bears, they’re not all the same. You can’t just have a blanket approach to ‘this is what you got to do for bears,’” Found said. He sent his human-wildlife conflict specialist to Jasper, where there is a higher population of grizzly bears than in Waterton, to gain more grizzly bear experience.

“A lot of it is just based on an accumulative body of knowledge that’s acquired. What happened last year for bears, what worked, what didn’t work. A lot of it carries on because it’s the exact same bears,” he said, calling the approach “adaptive management.” Found said knowledge comes from a variety of sources, including Indigenous knowledge.

Waterton’s bear management policy still leans a bit into the fear basis, Found said. “I think it’s because there’s still this awareness that the biggest disaster is, in the perception of a lot of people, is going to be a bear killing someone and trying to do everything to prioritizing visitor safety.”

The Wildlife Guardians Program

Found is also the lead supervisor for the Wildlife Guardians Program. Previously known as “Living with Wildlife,” the program began at Waterton in 1999 and was renamed to the “Wildlife Guardians Program” in 2016. Although wildlife guardian programs exist in many national parks across Canada, Waterton Lakes’ program uniquely became the first park in the country to have a fully Indigenous team in 2022.

The decision to have an all-Indigenous guardians team, Found said, is a result of the influence of the federal government’s interest at furthering reconciliation within the parks. The reason came from the desire to get an increased perspective on grizzly bears and wildlife management as well as to increase education with visitors on wildlife.

Found said the communication between the guardians and park visitors, especially from Indigenous perspectives, is one of the greatest management strategies when it comes to bear management.

“Our guardians are out there talking with people, probably more than our duty officers are,” Found said. “We have to be very conscious about that message. We don’t want to be telling people, maybe some prevailing messaging about bears, like they’re so scary, they’re so bad, they’re just a danger, they’re just a risk.”

Found said while a lot of people visiting the park have a high respect for bears, building that respect is something they want to continue. “That’s something where having this Indigenous perspective can be helping enforce that and convince people as well,” he said.

Found acknowledged that many Indigenous perspectives, particularly those of the Blackfoot people, come from a place of respect, and he said the Indigenous wildlife guardians is the best way Waterton is helping to improve the management of human-wildlife conflicts.

Kelly Tailfeathers, a resource management officer at Waterton Lakes, was the wildlife guardian team lead for 2022, working to supervise, recruit and build the all-Indigenous team. A member of the Kainai Blood Tribe, this was his second consecutive year working with Parks Canada after previously working with the aquatic invasive species team.

“From the Blackfoot perspective, the grizzly bear is a highly respected relative, a friend and associate. We respect all animals that are present here in our lands. The Creator placed every animal for a particular purpose in relation to the Matapiiks — the people,” Tailfeathers said.

“The grizzly bear is known as a protector and is known a powerful animal.”

Rob’s Story

Rob Found is the wildlife ecologist at Waterton Lakes National Park. Photo by Joy SpearChief-Morris.

Kelly’s Story

Kelly Tailfeathers was the Wildlife Guardians Program lead at Waterton Lakes National Park in 2022. Photo by Joy SpearChief-Morris.

Tailfeathers said respect for bears, and wildlife generally, in the Blackfoot culture guides his work each day.

“Every morning before I leave, I’ll smudge and say my prayer for the day to be safe, my coworkers to be safe, and that’s a part of our way of life is prayer, and we pray for the animals as well,” he said.

Tailfeathers said the all-Indigenous wildlife guardians team has been a meaningful employment opportunity by Parks Canada. “We bring our way of life here every day, and it’s a good way to show respect for the many cultures that visit the park here,” he said.

From May through September, Waterton Lakes brought on six people from the Blood Tribe, Saskatoon and Calgary to staff the guardians program for a six-month contract. Operating in teams of two, the wildlife guardians patrol the park, the Blood Tribe Timber Limit and the bison padlock in specialized vehicles. In shifts they monitored for potential incidents and educated park visitors along the way.

Kelly Tailfeathers rides around in his vehicle as part of his position as a resource management officer within Waterton Lakes National Park. Photo by Joy SpearChief-Morris.

Kelly Tailfeather’s car is equipped with a radio to communicate with the human-wildlife officers and others on the resource management team. Photo by Joy SpearChief-Morris.

Although they deal with general park safety, such as hiking in groups and having a safety plan, they also monitor wildlife like deer, elk and the very familiar bighorn sheep that like to wander into town. Bears appear to take up the most of their efforts as they are the largest attraction for visitors, Tailfeathers said.

The guardians check campgrounds to make sure there is no garbage out that can attract bears and clear out bear jams — a traffic jam caused by a bear being on or by a road — on roadways. Many of these incidents, Found said, are caused by human negligence.

“We’re trying to educate the people to be bear conscious, be bear safe and watch your food. Keep your food secured and not to be throwing garbage out of vehicles or feeding bears on the parkway, just to be cautious of all your activities,” Tailfeathers said. “There are park rules that need to be followed for the safety of both the animal and the tourists that visit the park.”

The guardians have also been involved in bear safety workshops in the Kainai and Piikani nations as well as workshops with the Blackfoot Confederacy surrounding wildlife scenarios.

Found said Waterton Lakes is also forming a resource conservation Indigenous advisory group with the motivation of continuing initiatives with the Blackfoot people including managing shared bear habitat in the Blood Tribe’s timber reserve, which resides within the park’s boundary. The group is currently in discussions with the park.

“We want bears across this whole habitat, and that’s one of the motivations for having a joint advisory group where we can actually have Indigenous people talking with us — so we’re not just making all these decisions — but also that we’re getting informed from Indigenous perspectives and also the Indigenous objectives as well,” Found said.

“I’m very hopeful that with the development of this new advisory group, that’ll also help us get some of this other forms of knowledge.”

Tailfeathers feels the recent movement towards reconciliation in Canada, particularly the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s 94 Calls to Action and Orange Shirt Day, are showing more inclusion of Indigenous knowledge and stories in mainstream culture.

“We’ve always been here and I don’t think we’re leaving,” he said. “As Blackfoot people, our language is still here, our way of life.”

Kelly Tailfeathers stands in the road in Waterton’s townsite. The lead for the all-Indigenous wildlife guardian team for 2022, he says bear management was most of his team’s efforts. Photo by Joy SpearChief-Morris.

Conclusion

Misconceptions about the nature of grizzly bears led to a system which continuously treated them as dangerous man eaters to be managed with fear and aggression. But the inclusion of Indigenous knowledge and a better understanding of how to respect the role bears play in the prairie and foothill landscape is changing how they can be managed in the future.

Indigenous understandings of bears as beings to be treated with respect has led to the shifting of both public and institutional understandings of grizzly bears within Parks Canada. As the wildlife guardians program shows, the more people respect bears, the better chance Parks Canada has of shifting the public’s attitude to how they, and their natural territories, are treated.

Pa’ksíkoyi has lived on this landscape before humans and they have had more to teach us, as the Blackfoot stories have said, then we can ever hope to teach them through our own actions.