inside the hanawon

“You know you are close when you can smell the cow poo,” says Eunice Jeong while in a van headed towards the North Korean women’s Hanawon. Jeong leads six volunteers to teach English at the resettlement support facility several times a month.

House of unity

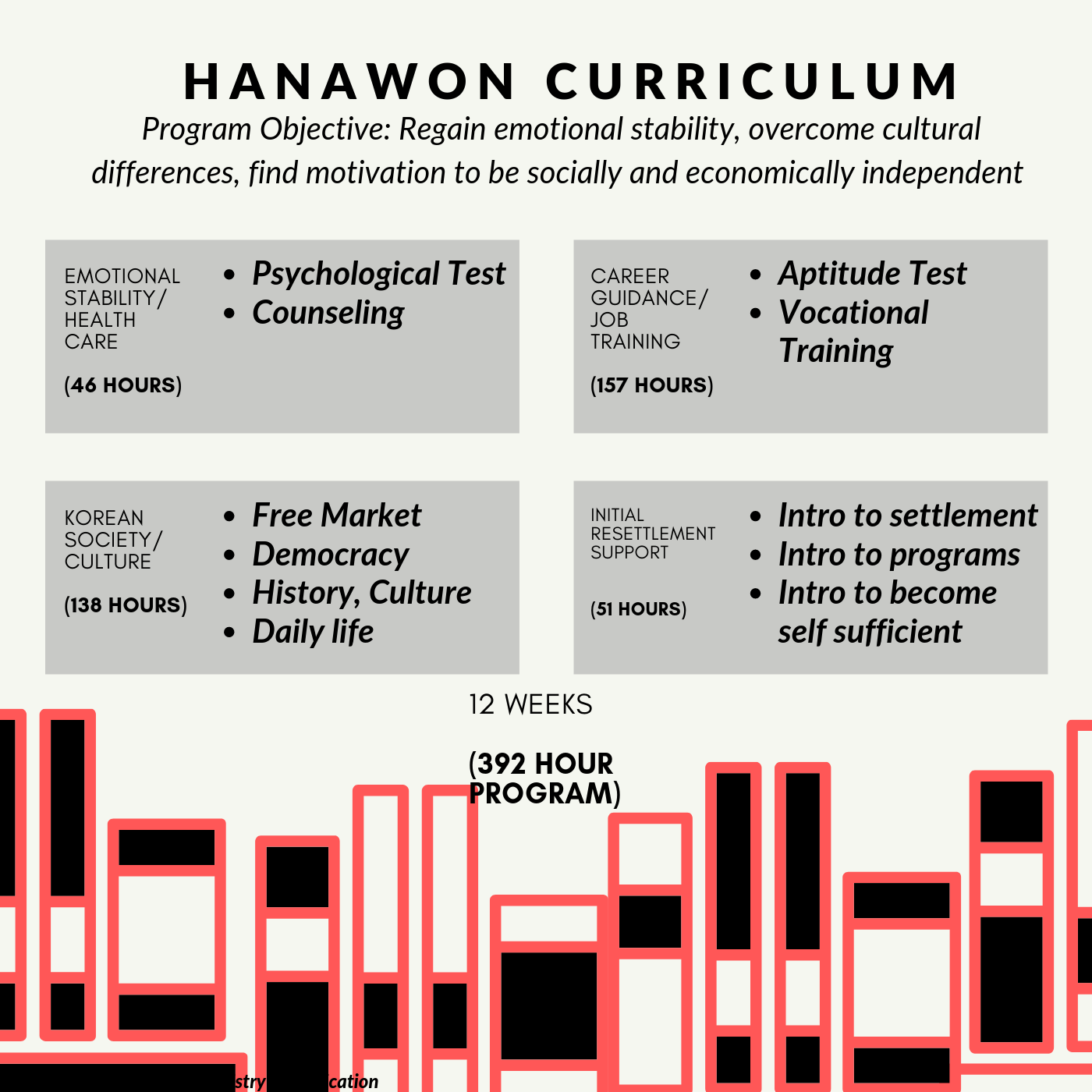

Hanawon means “house of unity” in Korean. Every North Korean refugee must spend 12 weeks there before they are resettled into homes around South Korea. The Ministry of Unification (MOU) funds the Hanawon, where refugees go through 392 hours of “social adaptation” training.

According to the MOU, the purpose of the Hanawon is to help North Korean refugees, “regain emotional stability, overcome cultural differences and find motivation to become socially and economically independent.”

The van departs in daytime through heavy traffic, smog and high-rise apartments. In less than forty minutes the landscape changes to windy roads, rolling green hills and farmland. When the van pulls into the tall barbed wire gate, every volunteer checks in with security and surrenders their cellphones. No photos are allowed inside the centre.

Colourful swing sets and manicured shrubbery line the grey sidewalk to the grey education hall. The inside of the building, also grey, smells earthy and is cold. On the first floor there is a massive bulletin board with a job opportunity for a barista and an advertisement for computer training. Outside of the classroom there is a flat-screen TV airing a South Korean news broadcast. Beside the TV there’s a large poster of a united North and South Korea. The volunteers write their names on the board and wait for their students. An announcement comes over the loudspeaker.

“They are telling the sisters we are here,” says Jeong. After a few minutes, North Korean women shyly appear in the doorway. The volunteers welcome them into the classroom. Soon the whole front row fills up with students. Every woman wears one of three different coloured collar shirts. Each colour corresponds with the time they entered the Hanawon – one, two or three months ago.

Everyone who enters the Hanawon must surrender their phone to the security guards. Before 2018, security would allow volunteers to keep their phones, but they would tape the camera. No photos are allowed inside the Hanawon for the protection of North Korean defectors. [Photo © Ash Abraham]

Welcome home, first stop: Interrogation

The Hanawon is the second stop for all North Korean refugees who settle in South Korea. First, they spend three months at the National Intelligence Center. South Korean officials interrogate refugees about their life in North Korea and journey to the South. According to the the National Intelligence Center, its work is to:

“Protect North Korean refugees at the North Korean Refugee Protection Center for three months when they enter the ROK…and carry out basic quality education for their early settlement in the Republic of Korea.”

The purpose of the interrogation is two-fold: to gather intelligence about North Korea, and to weed out any North Korean spies who may be posing as refugees.

After leaving the NIS facility, refugees move to the Hanawon. There is a separate facility for men and women. Besides vocational training, refugees must attend classes on democracy, capitalism and South Korean culture. Refugees go on outings to the bank and grocery store to see how a free market works. They also learn how to use public transportation and set up a bank account.

Second stop

Refugees are also assessed for physical and mental health issues. The Education Planning Division of the Hanwon explains:

“Refugees have to endure many traumatic experiences during their escape from North Korea. Most of them come to us with severe post traumatic stress disorders (PTSD). Years of malnutrition and lack of medical treatment in North Korea has caused many of them to have chronic diseases or serious drug addictions. Some refugees suffer from gastrointestinal symptoms, sleeping disorders and depression.”

Each refugee must complete 46 hours of “Emotional Stability and Health Care” training. Refugees learn about the South Korean healthcare system and where to receive support when they leave the Hanawon.

Next: Citizenship

At the end of their 12 weeks, North Korean refugees receive South Korea citizenship. Some refugees relocate to cities where they have family. For refugees who arrived to South Korea without family, a lottery system determines where they move.

Maintaining friendships with other women in the Hanawon can be difficult since the lottery system may assign refugees to different cities across the country. Plus, once the women leave the Hanawon they must scramble to find employment before the government funding runs out. Despite the challenge of staying in contact with women once they leave the Hanawon, Euncie Jeong manages to meet with several women every week for English tutoring.

At the end of every English lesson at the Hanawon, Jeong asks the class who among them will be graduating. When a few women in matching shirts raise their hand, Jeong and the other English teachers hand out a small gift and sing a send-off song for the soon-to-be graduates:

May love and happiness

Peace and joy

Be with you, forever

Wherever you are

The simple lyrics reflect Jeong’s approach to teaching English to North Korean women. Some may never contact her once they leave the facility, but she wishes them all well.

After North Korean refugees go through the Hanawon program, they become South Korean citizens. [Photo © Moon Hye In, used with permission]

Final destination: Seoul and Beyond

Across the street from the Hanawon are stretches of farmland. A lone bus zooms by a sun-cracked bus stop.

The Hanawon security guards return the cell phones to the volunteers. The English teachers pile into the van and head back to Seoul.

In a few weeks every North Korean woman from the English class will leave the pastoral setting of the Hanawon, and be dropped off in one of the most bustling cities in the world.