Jessie’s Story

Jessie Kim reaches for her phone and texts her “foreigner” friend from inside her tiny Seoul apartment. Kim spent the entire four-day Chuseok holiday alone. Most people in South Korea go back to their hometown and visit family for the harvest celebration, but for Kim that is impossible.

“I am sad,” Kim texts.

After a few minutes the Canadian friend texts her back, “Why are you sad?”

“I have no parents,” she responds.

“Come to my house. Let’s eat together,” the friend writes.

Kim texts back, “I will go to your home.”

Kim rides a bus over an hour outside of Seoul to visit her friend. It is the first time she visits a non-Korean person’s apartment. After spending an afternoon together eating and speaking with phrases of English and Korean, Kim takes the bus back home.

She texts her friend and writes, “I am happy.”

It had been a long time since Kim felt happy. Just six months earlier she was hiding out in the jungles of southern China. Before that she was in North Haesang, a province of North Korea.

a food stall in Pyongyang, North Korea. [Photo © Will Scott, used with permission]

Daily life in North Korea

Kim was the only child born to a college professor and homemaker. Her mother passed away from liver cancer when Kim was in primary school. After her father remarried, Kim moved in with her grandmother and dropped out of school. At only 14 years old she began selling liquor on the black market.

“After Kim Il-Sung died, we went into the starvation period,” says Kim. “The government’s slogan was ‘self-reliance.’ You had to take care of yourself. You had to feed yourself.”

Even as a child, Kim had a knack for running a business. She bribed local officials with cash. They turned their heads and allowed her illegal business to grow. Kim began exchanging soju (rice alcohol) for grain and moved it across the Chinese border. When she ran out of soju, she would make it herself. Business expanded, and she had more money than she could spend.

Video © Ash Abraham. [Photo © Roman Harak, used with permission]

Before the Korean War, Kim’s family lived closer to the border of North and South Korea. After the peninsula was divided, the new North Korean authorities sought out families who didn’t fully support the government. Those families were sent to northern provinces and treated as political criminals.

Kim found out that her family had sympathized with South Korea.

“In school we were taught that Americans were devils that kill people,” says Kim. “But when I asked my grandmother if that was true, she said no – the Americans gave us chocolates.”

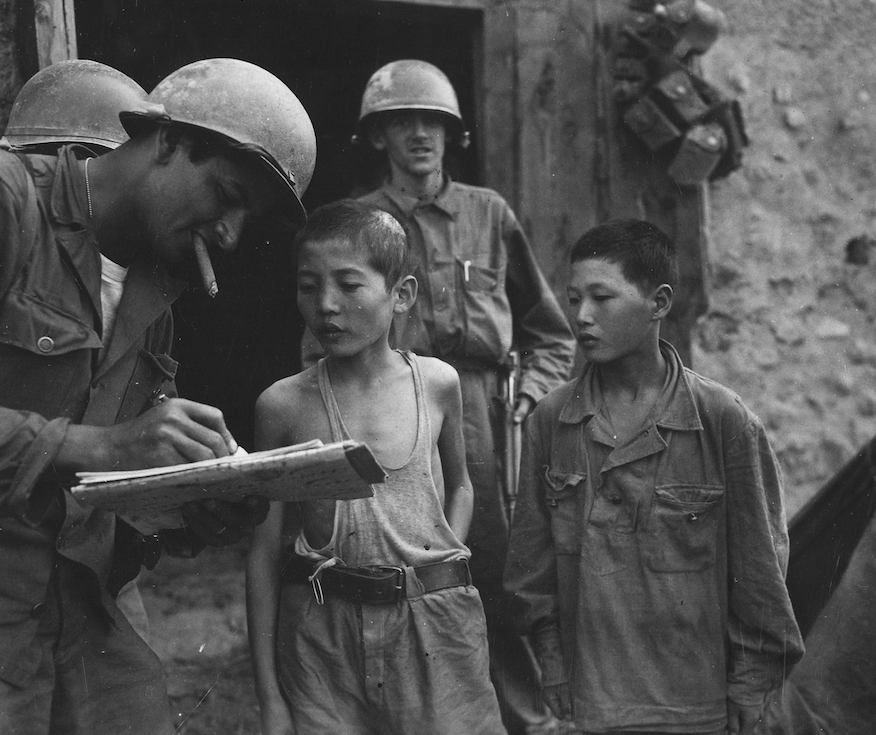

North Korean refugees with U.S. solider. Korean War, 1952. [Public Domain U.S. Army]

An unforgettable day

“I cannot forget that day,” Kim says of September 4, 2010.

Kim’s uncle was a poor man and was jealous of her thriving business.

“He picked fights and didn’t like that I was making more money than him.” Kim invested all of her savings into a large bag of pine nuts which she knew would sell for a high price. She hid the bag inside her house. While Kim was away from her house, her uncle went to the police. He told them to check his niece’s home for illegal contraband. The authorities searched Kim’s house and immediately confiscated her pine nuts. Within a matter of minutes, Kim’s lifesavings was gone.

“After that I had no faith or trust in family,” says Kim. “Because my father shared the same blood as my uncle, I held a grudge against him too.” Kim immediately started planning her escape from North Korea. She wanted to be as far away from family as possible. She reached out to her black market contacts in China, and over the next few months arranged a place for herself and a friend. After fixing her plans, Kim told her aunt that she was leaving for China the next day. Her aunt begged Kim not to leave – saying she would personally pay Kim back for the pine nuts.

Flight to China

But Kim was not only angry about the money. She told her aunt, “I am not leaving because of money. I am leaving because there is no trust in family. Don’t look for me in the morning, because I am not going to be here.”

Kim and a friend crossed the Aprok River in February of 2011.

“I had this fear like what if I die here, and no one knows who I am? I didn’t cross the river to have fear,” says Kim.

Kim lived in China for nearly two years, before she arranged travel with a broker across southern China and into Thailand. The broker guided an entire group of North Koreans from safe point to safe point. While other North Koreans shared their grand hopes about a new life inside South Korea, Kim thought to herself – “All I want is my own name.” She had lived in China without any documentation, and was eager to receive a South Korean passport.

Jessie Kim crossed the Aprok River between China and North Korea with her friend. [Video © Ash Abraham. Art by Golbon Moltaji]

In Seoul

Seoul is a city of nearly 10-million people. [Photo © Ash Abraham]

[Source: UN Population Fund. Visual © Ash Abraham]

“After leaving Hanawon, I came to the realization that I was alone. I had no idea where to go. I didn’t know how to take a bus or how to make a cellphone call. I didn’t know what to do with my life,” Kim says.

According to a 2017 Survey conducted by South Korea’s Ministry of Science and ICT, 99.4 per cent of South Koreans use KakaoTalk instant messenger for communication (e.g. chat or social network service). Average working class people in North Korea do not have internet access. One of the first things North Koreans do after leaving Hanawon, is get a phone and learn how to use KakaoTalk. [Photo © Ash Abraham]

The differences between North and South Korea also weighed on her. Particularly, people’s perceptions of North Korea. She recalls a time when a teacher hurt her feelings.

“The teacher said, ‘No matter how hard you try, you can’t be South Korean, because you’re from a different world.’ That really hurt me.” Kim says there are ups and downs to making friends with other North Korean refugees. There is a kinship and immediate understanding among North Korean refugees, but there are still nuances in terms of education and background.

Kim had better luck forming friendships with English teachers. The South Korean teachers helped prepare her for college entrance exams, and also provided emotional support when she was lonely.

Jessie Kim talks about her new life in South Korea with her former English tutor Eunice Jeong. [Video © Ash Abraham 2018]

“There was one lady who offered me English classes and she was very good to me, she was like my mom. She was the one person I could talk to. She was really kind and I confided in her like a mom,” says Kim.

Kim says there are times when she wishes she could go back to North Korea and visit her parent’s burial sites. But she doesn’t want to live under the regime anymore.

Ambassador of North Korean stories

Kim’s life has significantly changed since her first Chuseok in South Korea.

“That first Chuseok in South Korea, I felt really bad. I couldn’t visit my mom’s cemetery,” she remembers.

Kim’s father died before they were able to reconcile. She no longer has any living family ties in North Korea and can go public with her story.

She became an Advocacy Fellow for the NGO Liberty in North Korea (LINK), and learned how to become a public speaker on North Korea issues. Since Kim became involved with LINK she has made international friends and contacts around the world. Although, she still earns a meager living as a student, she is grateful to have freedom in South Korea.